Cardiac Diseases and Rehabilitation Services

Epidemiology

In 2001, cardiovascular diseases were still the first among the leading causes of death in men and women of all ages in the USA, with coronary heart disease (CHD) alone accounting for 54% of all cardiovascular deaths. The prevalence of cardiovascular diseases—including CHD, stroke and hypertension—increases with age up to more than 70% at age 75 years and older. A surveillance study performed by the National Heart, Blood and Lung Institute in 1987–2000 reported that the incidence of first heart attack is also increasing exponentially with age.1

Thanks to the remarkable advances in the management of acute CHD events, chronic heart failure (CHF) and cardiovascular risk factors, the specific mortality for heart disease has been declining continuously during the last two decades, especially among men. Furthermore, preventive medicine has shifted the age at which patients develop CHF but has not reduced, and indeed may have increased, its global epidemiological burden. As a consequence, growing numbers of cardiac patients currently survive longer, but with substantial functional limitations that are secondary to several manifestations of CHD, such as CHF, whose incidence has been increasing steadily, particularly in older populations, suggesting that we now face a real ‘CHF epidemic’. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) epidemiological study reported that the prevalence of CHF is less than 5% among individuals aged 65 years or younger, but doubles among those older than 75 years,2 and data from the World Health Organization (WHO) suggest that these figures differ little around the world, at least in more affluent countries.

As is discussed in this chapter, randomized clinical trials, and also meta-analyses and observational studies, have demonstrated that integrated cardiac rehabilitation (CR) programmes are highly effective in accelerating functional recovery and in improving exercise tolerance, adherence with secondary prevention measures, health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and also long-term prognosis after acute cardiac events.3–6 As a result, the most recent guidelines clearly define the core components and outcome measures of CR and secondary prevention programmes and indicate CR as an integral component of long-term care of patients with CHD and CHF.7, 8

Utilization of Cardiac Rehabilitation Services: An International Perspective

Despite this considerable amount of evidence and the fact that CR programmes are recommended (class I) by the European Society of Cardiology (ESC),9 American Heart Association (AHA) and American College of Cardiology (ACC)10 in the management of CHD and CHF,11 prescription of CR programmes and diffusion of CR services are still relatively limited.

The level of CR service coverage across the European Union could be estimated from a survey of 454 phase 2 (medium-term recovery after hospital discharge) and 383 phase 3 (long-term maintenance) centres in 13 countries. Fewer than 50% of eligible patients participate in CR rehabilitation programmes in most European countries, with services in particularly short supply in countries with the greatest burden of cardiovascular diseases.12 According to another survey of the European Society of Cardiology, only 67% of patients are prescribed CR soon after coronary artery bypass surgery, and this proportion drops to 49, 35 and 17% among those with recent myocardial infarction, coronary angioplasty or chronic myocardial ischaemia, respectively. Furthermore, utilization of CR services is widely variable cross-nationally, with an average participation after any type of CHD event ranging from 4% in Spain to 71% in Slovenia.13 In the recently published results of the third EUROASPIRE Survey, the scenario is similar: less than 50% of CHD patients were advised to participate in a CR programme after hospitalization and about 75% of those advised attended at least half of the sessions; in summary, only about one-third of the originally eligible population.14 More importantly, the data are limited to patients younger than 70 years who, in that survey, were selected for obtaining information on CR service coverage. Given the almost systematic exclusion of older patients that has been reported also by the most recent meta-analyses of CR in patients with CHD15 or CHF,16 under-prescription is expected to be even more marked in the older subset of the clinical population of cardiac patients.

Under-prescription of CR is similar in the USA, where only about 20% of appropriate candidates of any age, and about 10–15% of those older than 70 years, are estimated to participate in CR programmes, despite this treatment being acknowledged and recommended as a key component of secondary prevention programmes also in subjects older than 75 years.17

Cardiac Rehabilitation: Definition and Aims

CR is defined as the ‘sum of activities and interventions required to ensure the best possible physical, mental and social conditions so that patients with chronic or post-acute cardiovascular disease may, by their own efforts, preserve or resume their proper place in society and lead an active life’.18

In this perspective, CR and secondary prevention are aimed at (a) preventing the disability that may result from heart disease, particularly in older persons and in those with occupations implying physical exertion, and (b) preventing subsequent cardiovascular events. These goals can best be achieved through programmes combining the use of evidence-based prescription of drug therapy with exercise training and education, counselling, behavioural strategies and psychosocial interventions to help patients optimally control their coronary risk factors.15 Therefore, CR is an integrated process of care, the aims of which are well beyond the simple functional assessment and prescription of exercise (Table 45.1), and which is currently indicated not only for cardiac patients already disabled or at increased risk of disability, but also for those with a diagnosis of CHD, intermittent claudication or with coronary risk factors. The benefits of CR programmes have been well documented in young and middle-aged CHD patients, whereas older patients rarely have been included in CR programmes and are poorly represented in clinical trials.19, 20 On the other hand, one randomized clinical trial did show that CR is at least as effective in older as in adult patients.21 Despite such evidence, older patients are still less likely to be referred to formal CR programmes and, when referred but not encouraged enough to participate, in general experience a poor compliance with programmes. At least in part, the scant referral of older patients to CR programmes could be related to their more compromised clinical and functional status, due to frailty and greater burden of comorbidity resulting in disability.

Table 45.1 Aims and role of cardiac rehabilitation as an integrated secondary prevention tool.

|

Although epidemiological data show that patients aged 75 years and older requiring cardiac care are increasing, only limited age-specific data are so far available from observational studies reporting CR in elderly individuals.22 Most of these data refer to patients with an average age <75 years,21, 23, 24 and from studies of post-infarction CR with small numbers over 75 years of age.21 Nevertheless, several studies have demonstrated that, compared with adults, older patients derive from exercise-based CR similar, and sometimes greater, relative improvements in exercise tolerance and self-reported physical function. Suaya et al. recently demonstrated in a large cohort of older US Medicare beneficiaries, who had been hospitalized for CHD events or myocardial revascularization, that CR users had a better five-year survival.25 After fully adjusting for a series of potential confounders, depending on the analytical procedure, mortality rates were from 21 to 34% lower in CR users than non-users: results similar to those observed in randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses in younger populations. Mortality reductions extended to all demographic and clinical subgroups, including patients with recent myocardial infarction, recent myocardial revascularization or CHF. Interestingly, the benefit was progressively greater with advancing age and reached the maximum at 85 years or more. Unfortunately, only 12% of initial total population was prescribed CR. CR users with 25 or more sessions were 19% less likely to die over 5 years than matched CR users with 24 or fewer sessions (p < 0.001). The association of number of CR training sessions with outcome has recently been confirmed in another large cohort of older patients.26

The progressively shortened in-hospital stay after an acute myocardial infarction (from about 10 to only 4 days in the past 20 years)27 reduces the risk of physical deconditioning, but also the time available to check physical activity and promote the lifestyle changes that are necessary to reduce cardiovascular risk; this reinforces the need for CR programmes that function as comprehensive, secondary prevention services and are based in-hospital, and also in the community or at home. Chow et al., recently have demonstrated that early lifestyle modifications (within 1 month after acute CHD events) strongly predict short-term prognosis, reducing the six-month risk of myocardial infarction/stroke/death.28 For this reason, behavioural modification should be given priority similar to other preventive medications immediately after acute coronary syndromes.

Owing to better clinical management of cardiac diseases leading to improved survival rates, and to increasing evidence on the beneficial effects of CR in a wide range of cardiac conditions, the delivery of CR has changed remarkably over the past 30 years. In the 1960s, patients recovering from uncomplicated myocardial infarction accounted for almost the totality of referrals for CR. Complicated post-infarction patients or patients recovering from myocardial revascularization have also been enrolled in CR programmes in later years. Patients once considered at too high risk to participate in CR programmes, such as those with persisting myocardial ischaemia, CHF or harmful arrhythmias, are currently enrolled in CR programmes based on more gradual, protracted and, most often, supervised exercise training.6, 29, 30 Furthermore, as a result of the progressive ageing of the population, CR should now be provided to increasing numbers of older patients, characterized by more complicated coronary illness, comorbidities,6, 31 functional or cognitive impairment, emotional disorders or social isolation, which all may concur to reduce the enrolment rate in, and adherence to, standardized CR programmes. Paradoxically, although some of these factors represent specific indications to CR, female gender, older age, a low formal education and, most importantly, functional impairment, are all negative predictors of enrolment in CR. Therefore, CR centres have to become familiar with the aims and skills of multidimensional geriatric assessment, to implement strongly individualized programmes that may promote the extension of CR to frail, older individuals.

Studies have proven that CR is at least equally effective in younger and older cardiac patients,31 even those as old as 86 years,32 to improve their exercise tolerance and HRQOL. However, no one study has yet demonstrated the efficacy of CR with respect to outcomes that are most typically desirable in geriatric medicine, such as reverting or limiting the progression of functional dependence in frail, older individuals.

Secondary Prevention Strategies in Integrated Cardiac Rehabilitation Programmes

Guidelines indicate that secondary prevention should be based on non-pharmacological and pharmacological interventions that can reduce the risk of new events and disease progression and should be aimed at improving both the prognosis and HRQOL. Non-pharmacological interventions consist of education, counselling and psychosocial interventions targeted at smoking cessation, improving dietary habits, controlling body weight and increasing physical activity and long-term adherence with prescriptions.

Educational Principles

A meta-analysis of 37 trials33 found that CR programmes including psychological and/or educational interventions resulted in a significant reduction in incident cardiovascular events at 1–10 years, with studies with the greatest response to intervention showing the greatest impact. The desirable characteristics of the educational and counselling approach have been outlined after a meta-analysis demonstrating that the most important determinant of effectiveness is the quality of intervention,34 defined as behaviourally oriented interventions adhering to the five principles of adult learning:

- relevance (tailored to patients’ knowledge, beliefs, circumstances)

- individualization (tailored to personal needs)

- feedback (informed regarding progress with learning or change)

- reinforcement (rewarded for progress)

- facilitation (provided with means to take action and/or reduce barriers).

Behavioural techniques such as self-monitoring and personal communication, including written or audiovisual techniques, may further improve the outcome, with information provision alone found to be less effective.

Psychosocial Interventions

Some anxiety and depression are found in at least 20–25% of patients with various forms of heart disease but, particularly when they persist, should not be accepted as an appropriate reaction to heart disease. Emotional disorders reduce exercise capacity,35 HRQOL and adherence to secondary prevention measures and substantially increase the risk of new events. Depressive disorders are probably more common among older patients, who frequently suffer from isolation and financial constraints, which are negative prognostic factors after myocardial infarction. However, the long-term consequences of emotional disorders among older cardiac patients in CR programmes have been poorly addressed, and patients 75 years of age and older are at higher risk of under-recognition and under-treatment of depressive disorders.

Randomized trials proved that early psychological interventions improve the mood of middle-aged cardiac patients,36 but information on efficacy at older ages is not available. However, particularly for most severe or disabling cases of persisting depression, psychological support therapies should be used in conjunction with antidepressants. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, such as sertraline, which was proven to be safe and effective in a randomized trial enrolling patients depressed after an acute coronary syndrome, are probably the agents to be preferred.

Smoking Cessation

A Cochrane review confirmed the beneficial effects of smoking cessation, which reduces the risk of new events by up to 40%,37 similarly to what is seen with pharmacological correction of other cardiovascular risk factors. Smoking induces chronic dependence that makes relapses highly probable. Systematic encouragement of smoking cessation is based on the ‘5A-strategy’ of Asking, Assessing, Advising, Assisting, Arranging. In this process, it is necessary to identify smokers, to evaluate the degree of their dependence and their willingness to quit, to support those who are trying to quit with behavioural counselling, prescription of nicotine substitutes and participation in educational meetings, with regular follow-up visits.

Healthy Eating and Diet

Dietary prescriptions, adapted to local habits and individualized as much as possible, should be aimed at controlling body weight and provision of all elements of proven efficacy in secondary prevention. Dietary habits should be assessed objectively, with the use of reproducible questionnaires and checking individual knowledge of nutrients and of possible substitutes. Education, rather than prescription, should be provided, limiting dietary restrictions to patients with defined metabolic abnormalities. Education and counselling should be provided by professional dieticians, who perform better than physicians in obtaining a long-term reduction in plasma cholesterol levels.

Increasing Physical Activity

Promoting a long-term increase in usual physical activity is a fundamental objective of integrated CR programmes finalized at secondary prevention. Regular physical exercise improves the lipid profile and delays the progression of CHD in middle-aged, male patients and reduces cardiovascular mortality in the general population. In the Harvard Alumni Health Study,38 the relative (i.e. perceived) intensity of physical activity was a strong predictor of lower CHD rates, with a clear dose–effect relationship and an effect that was similar, if not superior, among subjects older compared with those younger than 70 years. Interestingly, the absolute intensity of physical activity did not perform as well as the relative intensity in distinguishing CHD risk groups, suggesting that physical activity recommendations need to be individually tailored. Standard recommendations of regular performance of activities at an intensity of at least 3 METs (Metabolic Equivalents, 1 MET corresponding to 3.5 ml of oxygen consumption per kilogram of body weight; see also below) may therefore be inappropriate, especially for older persons.38

Long-Term Adherence and Follow-Up

Once the process of short-term recovery is complete, the emphasis of CR shifts to long-term maintenance of physical activity, lifestyle changes and prophylactic drug therapy, in the perspective of ‘comprehensive cardiac care’ as the final goal, following evidence-based recommendations.

A systematic review of 12 randomized trials of secondary prevention programmes in CHD found that structured disease management programmes improve risk factor profiles and secondary preventive treatment, while reducing hospital readmissions and enhancing HRQOL.39 The programmes included in the review differed considerably: all were multifaceted, with about half including medical and lifestyle treatments, and the rest were predominantly lifestyle and psychosocial interventions. Most were hospital based, but two conducted in UK primary care suggested that a structured approach benefits HRQOL and uptake of secondary prevention. Indeed, long-term adherence with recommendations and prescriptions made during CR is difficult to maintain, usually being reduced to 50–60% at 1 year and to 20–30% at 3 years. Therefore, to enhance long-term maintenance of the goals attained during CR, it is highly recommended that structured care and follow-up are provided in primary care and studies suggest that low-cost, physical training programmes carried out in the community are safe and help patients maintain the physical performance levels they had attained during hospital-based rehabilitation. The GOSPEL study, the results of which have recently been published, is the first trial to demonstrate that a multifactorial, continuously reinforced intervention up to 3 years after post-infarction CR is effective in decreasing the risk of several adverse outcomes, although statistical significance was reached for non-fatal reinfarction only.7

The Structure of Cardiac Rehabilitation Programmes

CR programmes usually consist of three phases, each representing a different step in the progression of individual patient care: in-hospital care, the early post-discharge and exercise training period and long-term follow-up. Common to each phase and irrespective of which model of CR is chosen, is the need for individually tailored interventions.

Phase I occurs during in-hospital stay, when a ‘step change’ (any acute coronary event, cardiac surgery or first diagnosis of heart failure) has occurred in a patient’s cardiac condition. Medical evaluation and treatment, reassurance and information aimed at reducing emotional distress, risk factor assessment, mobilization and discharge planning are the key elements during this phase.

Phase II includes the early post-discharge period—when baseline assessment and initial counselling on self-management of heart conditions usually take place—and subsequent structured exercise programmes, which are carried out either in a hospital setting or in outpatient clinics or, at least for selected patients, at home.32 Guidelines29 suggest that, for greatest secondary prevention success, training must be associated with educational and psychological support and advice on risk factors, such as smoking cessation and weight management, vocational rehabilitation to assist return to work or retirement and referral to a psychologist, cardiologist or exercise physiologist. It has been demonstrated that phase II programmes of integrated, multicomponent CR can be undertaken safely and successfully also in the community.

Phase III involves the long-term maintenance of physical activity and lifestyle changes. Available evidence suggests that both must be sustained for benefits to continue. Membership of a local cardiac support group, which involves exercise in a community centre such as a gymnasium or leisure centre and structured care and follow-up in primary care, may help maintain physical activity and behavioural change.

Baseline Assessment

Baseline evaluation is a process of crucial importance that has to be completed prior to enrolment in a cardiac rehabilitation programme. In this process, several clinical, functional and, particularly in older persons, emotional, cognitive and social elements must be taken into account, as they are used to assign the patient to the programme most appropriate for their clinical and functional conditions, to pursue reliable and clinically valuable outcomes, to reduce the probability of programme-related complications and to promote individual adherence to the programme. Exercise training programmes for older persons also need to take into account commonly associated comorbidities that can alter the modalities and intensities of the exercise that is required to produce a training effect. These include, but are not limited to, CHF, arthritis and osteoporosis, chronic lung disease, diabetes and peripheral or cerebrovascular disease.

Risk Stratification

Risk stratification and assessment of exercise capacity are the two fundamental steps of baseline evaluation. These two steps are closely linked, as information gathered with assessment of exercise capacity is used not only for an appropriate exercise prescription to each individual patient, but also as one of the criteria for assigning each patient to one risk category. Risk stratification will serve, on the other hand, to optimize pharmacological therapy and possibly to indicate the need for invasive procedures (e.g. coronary angiography and myocardial revascularization; implantation of pacemakers or intracardiac defibrillators), but also as further information to be taken into account for exercise prescription.

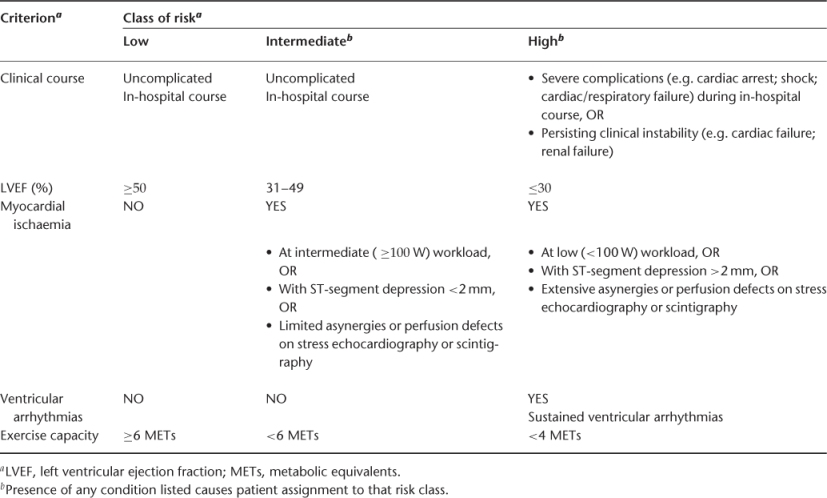

In essence, risk stratification relies upon the evaluation of clinical stability, left ventricular function, presence of residual myocardial ischaemia or of sustained ventricular arrhythmias and exercise tolerance. Following the criteria outlined in Table 45.2, patients are classified as at low, intermediate or high risk.

Table 45.2 Criteria for baseline risk stratification of candidates to a cardiac rehabilitation programme.

Assessment of Exercise Capacity

Baseline exercise capacity can be evaluated by several methods, among which the most commonly used are the ergometric stress test, the cardiopulmonary exercise test and the six-minute walk test. Each of them is indicated in different conditions and provides different information.

The ergometric stress test

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree