Abstract

Persons with cancer of the brain and spinal cord receive rehabilitative care in a variety of settings. These often include hospitals, postacute care facilities such as acute inpatient rehabilitation facilities, long-term healthcare facilities, hospice, outpatient rehabilitation facilities, and the person’s home. A truly integrated continuum of cancer care delivers both cancer and rehabilitative services using a treatment plan that provides the right care, at the right place, at the right time by personnel who are well versed in the principles of oncologic rehabilitation. This chapter explores the advantages and challenges to providing rehabilitative care in each of these settings.

Keywords

Cancer rehabilitation, Delivery care models

Introduction

Cancer rehabilitation has been defined as “medical care that should be integrated throughout the oncology care continuum and delivered by trained rehabilitation professionals who have it within their scope of practice to diagnose and treat patients’ physical, psychologic, and cognitive impairments in an effort to maintain or restore function, reduce symptom burden, maximize independence, and improve quality of life in this medically complex population.”

Persons with cancer often receive their oncologic care in a variety of settings such as acute care hospitals, long-term healthcare facilities, outpatient clinics, and the person’s home. This parallels the types of locations where they also receive their rehabilitative care. It is therefore important to have fully integrated oncologic and rehabilitative care across this continuum of care. The fundamental goal of rehabilitation of the person with brain or spinal cord cancer is to maximize function and to improve the quality of life regardless of the setting where they receive their healthcare.

To accomplish this goal, the person should first be evaluated for functional deficits by a rehabilitation specialist. This is meant to establish a baseline functional level and serves as the foundation for an individualized rehabilitation plan of care. The person should subsequently be screened periodically and treated for cancer-related impairments throughout their life across the rehabilitation continuum. The rehabilitative treatments need to be provided by an experienced clinical staff, in the most appropriate setting, and at the most appropriate time in the person’s cancer care. The management of functionally relevant impairments should be holistic and person-centered, addressing physical impairments, nutrition, emotional well-being, sexuality, spirituality, and the role of the individual in their family and society.

The aim of this chapter is to describe the components of the rehabilitative continuum of care and the advantages and challenges faced by each of these components in the provision of rehabilitative services to the person with cancer.

Barriers to the Provision of Rehabilitation Services to Persons With Brain and Spinal Cord Cancer

This current delivery model of rehabilitative care is hindered by several barriers as follows: (1) patients, their families, and medical providers may have a limited knowledge about the benefits of rehabilitation; (2) the families and significant others of persons with cancer are often overwhelmed by the complexity, cost, and limited resources and cannot fit rehabilitation into an already busy schedule; (3) a limited workforce of rehabilitation providers that has the necessary working knowledge and expertise to provide cancer rehabilitation services to persons with brain or spinal cord cancer; (4) a fragmented carryover of a rehabilitation treatment plan across the continuum of care; (5) lack of a coordinated plan of care that incorporates both cancer treatment and rehabilitation; (6) lack of use of standardized rehabilitation clinical protocols and outcome measures across the rehabilitation continuum; (7) lack of standardization of cancer rehabilitation programs across the United States; and (8) limited coverage for rehabilitation services by health insurance companies.

The Continuum of Care for Oncologic Rehabilitation

Dietz classified cancer rehabilitation using four distinct roles: preventive, restorative, supportive, and palliative. These fundamental roles can be applied and used to guide rehabilitative treatment from time of diagnosis, through acute cancer treatment and survivorship, and in the advanced stages of cancer. Preventive rehabilitation begins at the time of diagnosis when preexisting impairments are identified and treated. It is also an opportunity to optimize the individual’s level of physical and mental fitness using exercise, nutrition, and psychosocial interventions. Restorative rehabilitation focuses on maximizing the person’s level of function by addressing their impairments. For example, a person with cancer affecting the spinal cord and paralysis of the extremities would benefit from acute inpatient rehabilitation to address the corresponding deficits. Supportive rehabilitation focuses on improving self-care and mobility and maximizing function in persons with progressing cancer. Palliative rehabilitation aims to improve the level of function of the person with cancer in the advanced stages of the disease by managing symptoms such as pain and fatigue and addressing physical impairments that can limit function. It can also be used to minimize the risk of developing potentially preventable conditions such as pressure ulcers and contractures.

Acute Hospitalization

During the acute hospitalization period, the person with cancer often moves from one setting to another depending on their underlying condition and medical stability. It is not uncommon to have the person be admitted through the emergency room and spend time on a medical and/or surgical floor and/or in an intensive care unit in one hospitalization. As a result they can become deconditioned very quickly due to prolonged bed rest and use of steroid medications.

The goals of rehabilitation in this setting include the following: (1) minimize the deleterious effects of prolonged immobilization; (2) maximize patient safety (i.e., minimize risk of falls, development of aspiration pneumonia, pressure ulcers, contractures, and medication side effects); (3) maximize level of function for activities of daily living; (4) mobilize the patient if they are able to ambulate; (5) maximize nutritional intake; (6) educate the person and their significant others about cancer-related physical impairments; (7) address psychosocial stressors; and (8) assist the primary treatment team with discharge recommendations to the most appropriate setting.

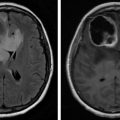

The physiatrist has a significant role in the coordination of rehabilitative services during an acute hospitalization. Through close communication with members of the rehabilitation team and referring physicians, the physiatrist can address the physical impairments of the person with cancer of the brain and spinal cord. In addition, he/she can make recommendations for discharge to the most appropriate setting for the patient. Rehabilitative services are typically provided at the bed side or in an inpatient gym in the institution. Under-referral of cancer patients to rehabilitation has been a chronic problem for the cancer rehabilitation specialty and has also been noted in the inpatient setting specifically. A recent Italian study by Pace et al. evaluated the rehabilitation referrals of brain tumors patients. Only 12.8% received inpatient rehabilitation, 3.1% received intensive outpatient rehabilitation, and 11.8% received traditional outpatient rehabilitation. Like traditional brain injury populations, neurologic deficits can include hemiplegia, spasticity, aphasia, dysphagia, ataxia, cognitive deficits, bowel/bladder dysfunction, visual symptoms including diplopia and dysarthria. Given that 75% of brain tumor patients have 3 or more neurologic deficits and 39% have more than 5 neurologic deficits, these low referral rates to rehabilitation for this patient group appear grossly inadequate. Some referring oncology services have been shown to lack understanding of what rehabilitation does and fail to identify impairments that rehabilitation can help treat.

A consult-based inpatient cancer rehabilitation program has been used at the Mayo Clinic–Rochester called the Cancer Adaptation Team (CAT) and MD Anderson Cancer Center called the Mobile Team. The CAT consists of a nurse, physiatrist, physical therapists, occupational therapist, social worker, nutritionist, and chaplain who meet daily to coordinate rehabilitation care. The MD Anderson Mobile Team enabled patients to receive up to 1 h of physical and 1 h of occupational therapy daily while still on the acute care service and met weekly. The idea was to provide a mobile acute inpatient rehabilitation type program for cancer patients. These rehabilitation models allow more intensive coordinated team-based rehabilitation led by a physiatrist while the patient is still on the acute care oncology service. The services have been particularly useful for medical fragile hematologic cancer patients but could also be used in a neurologic tumor population. Barriers to this model of consult-based rehabilitation include the Prospective Payment System and therapy resource availability.

The challenges of providing rehabilitative services in this setting include the following: (1) rapid changes in the person’s medical condition; (2) lack of knowledge about the role of physiatry and rehabilitation among oncologists and other healthcare providers involved in the person’s care; (3) delay in the identification and initiation of rehabilitative services; and (4) gaps in communication between the oncology and rehabilitation teams.

Postacute Care

Postacute rehabilitative care is most commonly provided in acute inpatient rehabilitation facilities (IRFs) as well as subacute and skilled nursing facilities. Common challenges to the provision of rehabilitative services in these settings include the following: (1) the rehabilitation plan not fully integrated into the oncology treatment plan; (2) significant variability in the type of rehabilitative services available in each of these settings; (3) lack of standardization in the treatment protocols for cancer-related impairments across the United States; (4) variable provider awareness of the benefits of rehabilitation for persons with cancer across the continuum; and (5) payer limitations.

Acute Inpatient Rehabilitation

Brain tumors are the second highest cause of neurologic disease and neurologic tumors account for over half of all cancer patient admissions to American acute IRFs. They are also the largest group of IRF patients at Shirley Ryan AbilityLab (formerly known as the Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago) and MD Anderson Cancer Center. However, cancer patients are only 2.4% of all US IRF patients and half of IRFs admit fewer than 10 brain tumor patients annually.

Neurologic tumors may be the largest group of IRF cancer patients for several reasons. First, the Medicare 60 percent rule mandates that, in order to participate in the Medicare Prospective Payment System, 60% of an IRF’s admissions have 1 of 13 diagnoses. Cancer and deconditioning are not 1 of the 13, which may discourage the acceptance of many cancer patients. However, brain injury is a 60 percent rule diagnosis and brain tumor patients would be considered brain injury. Because it is housed within a National Cancer Institute Comprehensive Cancer Center that is exempt from the Medicare Prospective Payment System, the MD Anderson acute inpatient rehabilitation unit does not have to adhere to the 60 percent rule. While lower than the proportions reported in the American national data or Shirley Ryan AbilityLab, neurologic tumors are the largest group of patients admitted to the acute inpatient rehabilitation service (17%) at MD Anderson.

In an IRF, patients are required to participate in at least 3 h of therapy per day for 5 days a week. They are also required to be seen by a physician at least three times a week but are typically seen more frequently. The vast majority of inpatient rehabilitation research in neurologic tumor patients has been in the IRF setting.

The medical fragility of cancer patients may discourage their acceptance to IRFs. It has been shown that general cancer patients are transferred back to the primary more frequently than noncancer patients. The hematologic cancer populations can be among the most medically fragile cancer patients with rates of return to the primary acute care service reported between 26% and 38%. However, the brain cancer rates of return to the primary acute care service (reported between 7.5% and 24%) are substantially lower and close to their traumatic brain injury (TBI) (20%) and stroke (7.1%) counterparts.

Logistical and regulatory barriers exist for IRF brain cancer patients receiving concurrent chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy. From a regulatory standpoint, the cost of concurrent radiation or chemotherapy can be significant and can cut into margins or make patient acceptance a money-losing proposition under the Medicare Prospective Payment System. This is an important consideration that is different from stroke and TBI patients who are usually finished with all diagnostic and treatment procedures prior to inpatient rehabilitation transfer.

Logistical considerations also exist. First, rehabilitation facilities may be unable to give chemotherapy due to lack of chemotherapy trained nurses and medical staff, pharmacy restrictions, hospital policy, or lack of accompanying monitoring such as telemetry (if needed). Radiation treatments can interfere with inpatient rehabilitation therapy times. While the radiation treatment is relatively quick (usually only 10–20 min.), the transportation to and from radiation can add up to a large part of the day gone from rehabilitation. Transportation often consists of ambulance transportation to a facility miles away. This may present challenges for therapists to provide the 3 h daily of therapy required in an IRF. Radiation-related fatigue, which typically occurs after the first few treatments, may interfere with rehabilitation therapy performance and tolerance. It may be beneficial to ask to schedule inpatient rehabilitation patients for the last radiation sessions of the day after they have completed their rehabilitation. By doing so, patients are able to sleep after the radiation and then wake up more refreshed in the morning while also eliminating the return trip transportation time from cutting into potential therapy time.

Patients with neurologic tumors often suffer from a number of cancer-related symptoms which can impact function and therapy tolerance. They can include fatigue, poor appetite, insomnia, cognitive deficits, depression, and anxiety. These patients are at risk for cognitive deficits not only due to the brain tumor and treatment itself but also exacerbating concomitant symptoms. Owing to their high risk, a screening speech therapy cognitive evaluation at inpatient rehabilitation may be of benefit because these deficits may not be obvious on casual conversation. Cognitive deficits can have discharge planning implications as well. Postacute brain injury rehabilitation programs may be a useful resource; however, they are only covered by some private insurance policies and not Medicare/Medicaid.

The substantial cancer symptom burden of inpatient rehabilitation cancer patients can impact function and therapy tolerance. Because of this, inpatient cancer physiatrists treat cancer symptoms and have been shown to make statistically significant improvements in symptoms likely from physical activity but also medication management. Owing to a cancer-related hyperinflammatory state, pain, fatigue, nausea, and insomnia can develop and make physical activity difficult. Cancer-related fatigue is experienced by over 80% of brain tumor patients during treatment. Neurostimulants have shown some benefit for cancer-related fatigue although their effects are less pronounced in placebo-controlled trials. Poor appetite may respond to appetite stimulants such as dronabinol and mirtazapine. Megestrol may be effective but also has a side effect of hypercoagulability which may increase the already high risk of venous thromboembolic disease. Depression and anxiety are treated much like the noncancer population. Psychotherapy may be of benefit. Mirtazapine is an antidepressant with weight gain effects and may be useful in patients with both cachexia and depression. Constipation is common among cancer rehabilitation inpatients due to immobility, neurogenic contributors, and frequent opiate use. Constipation can also contribute to nausea and poor appetite. Daily monitoring of bowel movements is encouraged. Patients with new-onset nausea or abdominal distension may benefit from an abdominal X-ray to evaluate the degree of constipation present. Aggressive use of laxatives may be required. Sexuality issues should be explored with a thorough history to determine contributing factors beyond just the neurologic but also cancer symptom–related contributors like depression and fatigue.

After a neurosurgical biopsy or craniotomy with resection, a specimen is sent for pathologic evaluation to confirm the diagnosis. Typically, the final pathology results are not completed until another week after the operation. By that time, many patients are on inpatient rehabilitation. Patients and their families are understandably eager to find out the pathologic diagnosis and then what prognosis is associated with it. Oncologists and neurosurgeons may be unable to visit with the patient and family in a freestanding rehabilitation hospital due to a lack of hospital privileges or distance. Because the physiatrist is often the only physician caring for a freestanding inpatient rehabilitation hospital patient, questions about the cancer diagnosis and prognosis may be directed at them. These conversations may be uncomfortable for a physiatrist due to unfamiliarity with the latest oncologic research and treatments but also their mortal nature. The oncologist is the most qualified person to answer these questions, but patients may have to wait until an oncology clinic after discharge to discuss them.

Subacute Rehabilitation and Long-Term Care Facilities

Persons with brain or spinal cord cancer who cannot tolerate the intensity of an IRF program as well as persons who completed such a program and are not ready to return back to their homes are often referred to rehabilitation programs in subacute or skilled nursing facilities.

The goals of rehabilitation in these facilities are similar to the ones mentioned earlier, which are as follows: (1) minimize the deleterious effects of prolonged immobilization; (2) maximize patient safety (i.e., minimize risk of falls, development of aspiration pneumonia, pressure ulcers, contractures, and medication side effects); (3) continue and modify as necessary the rehabilitation treatment plan initiated at the previous facility; (4) maximize level of function for activities of daily living; (5) mobilize the patient if they are able to ambulate; (6) maximize nutritional intake; (7) educate the person and their significant others about cancer-related physical impairments; (8) address psychosocial stressors.

The rehabilitation at these types of facilities is usually less intense on a daily basis than in IRFs; however, the person typically spends more days in these facilities. The physician in charge of the person’s care may or may not be a physiatrist, and their knowledge about the treatment of impairments commonly seen in brain and spinal cord cancer may be limited. Team members often include physical therapists, occupational therapists, and speech pathologists. However, these therapists may or may not have significant experience and education in cancer rehabilitation principles. It should be noted that there are facilities that have a focus on neurologic rehabilitation and as such will have a clinical staff that is better versed in the care of persons with these types of cancer. Another challenge is in care coordination between the referring facility and the subacute/skilled nursing facility with respect to the rehabilitation plan. A physiatrist can be very instrumental in facilitating the communication between these facilities with respect to the rehabilitation treatment plan.

Some subacute rehabilitation facilities are unable to administer chemotherapy due to lack of qualified staff. Also they may be reluctant to accept patients who require additional chemotherapy and radiation therapy because these often expensive treatments may come out of a Prospective Payment System payment. Skilled nursing facilities typically do not have blood bank transfusion capabilities, which may be an issue with pancytopenic chemotherapy patients.

Postacute Brain Injury Residential Rehabilitation

Some patients after completing an inpatient rehabilitation program may require additional rehabilitation in a residential type setting. Postacute brain injury rehabilitation facilities were designed for such patients and may be useful for patients with significant cognitive, behavioral, or social limitations. There has been little published regarding the experiences of brain tumor patients in these settings. Unfortunately, postacute brain injury rehabilitation facilities are not covered by traditional Medicare/Medicaid.

Home Rehabilitation

Once discharged from an acute IRF, a subacute rehabilitation program, or an acute hospitalization, the person with brain or spinal cord cancer often requires continued rehabilitative services, however, cannot attend an outpatient rehabilitation program. The reasons often include (1) limited access to transportation to and from the outpatient program; (2) an inability to tolerate the intensity of an outpatient program; or (3) limited health insurance coverage for rehabilitative services. The availability of home rehabilitative services can vary by geographic region as well as frequency and intensity; however, the goal is to make the person more independent in their home environment and to educate them and their significant others on strategies to maximize level of function. The main advantage to the home therapy program is the convenience of having the services provided in the home. The main disadvantage is the limited type of exercises and equipment that can be provided in the home setting by the treating therapist. The rehabilitation program is typically initiated by a referring physician who can then monitor the patient’s progress. As technology improves, telerehabilitative services could potentially be of benefit in both the education and the monitoring of the person with brain and spinal cord cancer at home.

Outpatient Rehabilitation

Persons with brain and spinal cord cancer often need multiple rehabilitative disciplines working together closely to address the complexity of impairments commonly seen in this population. This often includes physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech pathology; however, there are occasions when the services of an orthotist, neuropsychologist, vocational rehabilitation specialist, and driving trainer may be required. The physiatrist is best suited to coordinate the rehabilitation team efforts in the outpatient setting. The advantages to a comprehensive outpatient program include more focused rehabilitation interventions for gait and balance training, wheelchair transfers, and manual dexterity just to name a few, compared with those that can be accomplished in the home. The use of additional equipment commonly available in the gym setting is an added advantage over home therapy. Rehabilitation interventions in this population are often reimbursable by payers (task force). Challenges to the provision of outpatient rehabilitative services include (1) a rapid deterioration in the person’s medical condition secondary to the tumor often requires changes to the treatment plan and prioritization of goals (i.e., progression of cancer, seizures, newly identified impairments, etc.); (2) limited health insurance coverage for rehabilitation services; (3) access and transportation barriers to receiving rehabilitative services; (4) geographic variability in the availability of necessary rehabilitation services and in providers with experience in brain and spinal cord cancer rehabilitation; and (5) communication barriers between rehabilitation clinicians and their oncology colleagues.

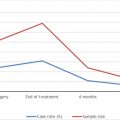

During outpatient supportive rehabilitation, patients may experience significant cancer symptoms related to radiation, chemotherapy, or other medications such as antiepileptics and analgesics. Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) patients receiving the Stupp regimen’s 6 weeks of radiation therapy may experience significant fatigue after their radiation session. If possible, scheduling radiation sessions later in the day after rehabilitation therapy may be useful. Patients will have an opportunity to sleep/rest and hopefully have more energy the next morning for additional rehabilitation. During the Stupp regimen, GBM patients receive oral temozolomide chemotherapy cycles for 5 days with 23 days off. During the 5 days of temozolomide, patients may experience increased fatigue and nausea, which may affect rehabilitation performance and tolerance. It may be best to reduce or temporarily suspend therapy during these 5-day periods.

An important distinction between brain tumor patients and the more typical brain injury rehabilitation populations of stroke and TBI are that brain tumors are dynamic lesions. The lesions can grow or recur over time, which can lead to further weakness and neurologic changes. Furthermore, cancer treatments can cause additional brain injury. Radiation late effects can cause new neurologic deficits typically months to years after radiation completion. It is not uncommon for brain tumor patients to require inpatient or outpatient rehabilitation multiple times over the course of their cancer due to declines in function from the cancer or its treatment. For high-grade astrocytoma patients, it is not a question of if these patients will experience neurologic decline in the future, but when. Therefore, continued outpatient physiatry follow-up is recommended. Also due to the dynamic nature of brain cancer, it is common over time for brain tumor patients to accumulate a number of brain injuries due to repeated surgical resections, cancer progression/recurrence, and radiation necrosis. The rate and degree of functional improvement is often reduced after each repeated bout of functional decline.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree