Cancer of the Urethra and Penis

Edouard J. Trabulsi

Leonard G. Gomella

INTRODUCTION

Penile and urethral carcinomas are uncommon malignancies, with a peak incidence in the 6th decade of life. Often overshadowed by more common genitourinary cancers, penile and urethral cancers represent difficult challenges for the treating physician. Squamous cell carcinoma is the most frequent type of cancer in the penis and the urethra. Carcinoma of the penis is a slow-growing tumor with a usually welldefined pattern of dissemination. This orderly spread allows definitive local-regional management of the primary tumor in most cases. In contradistinction, urethral carcinoma in men and women tends to invade locally and metastasize to regional nodes early. Depending on the site of the urethra involved and disease extent, a multimodal treatment approach may be required to treat this aggressive tumor.1

CANCER OF THE MALE URETHRA

Carcinoma of the male urethra is uncommon. Chronic irritation and infection are the strongest risk factors. The incidence of urethral stricture in men with development of urethral cancer ranges from 24% to 76%, and most of these strictures involve the bulbomembranous urethra, also the most frequent site of cancer.2 Human papillomavirus-16 (HPV-16) likely has a causative role in the development of squamous cell carcinoma of the urethra.3 No racial predisposition has been noted.

The onset of malignancy in a patient with a longstanding urethral stricture disease is often insidious, and a high index of suspicion is needed to diagnose these tumors early. The new onset of urethrorrhagia or urethral stricture in a man without a history of trauma or venereal disease should raise the possibility of urethral carcinoma. A palpable urethral mass associated with obstructive voiding symptoms is the most common presenting symptom.4 Pain associated with a periurethral abscess or urethral fistula may be the harbinger of a male urethral cancer.

Pathology

Overall, 80% of male urethral cancers are squamous cell, 15% are urothelial (transitional cell), and approximately 5% are adenocarcinomas or undifferentiated tumors.5 The anatomic location of urethral cancer largely determines the histologic type. Carcinomas of the prostatic urethra are urothelial in 90% and squamous in 10%; conversely, carcinomas of the penile urethra are squamous in 90% and urothelial in 10%. Adenocarcinomas of the urethra arise from metaplasia of mucosa or from periurethral glands, but direct invasion of rectal adenocarcinoma must be ruled out. Adenocarcinoma has the same prognosis, stage for stage, as the other histologies.4

The bulbomembranous urethra is most commonly involved (60%), followed by the penile urethra (30%) and the prostatic urethra (10%).4 The incidence of urethral involvement associated with carcinoma of the bladder has been estimated to be approximately 6%,6 and urethral recurrences after radical cystectomy occur in 4% to 17%.7

Male urethral cancer may spread locally to involve the corpus spongiosum or may metastasize to regional nodes. The lymphatics of the anterior urethra drain into the superficial and deep inguinal lymph nodes and occasionally to the external iliac nodes. The lymphatics from the posterior urethra drain into the external iliac, obturator, and hypogastric nodes. Palpable inguinal nodes are found in approximately 20% and almost always suggest metastatic disease, in contrast to penile cancer, where 50% of palpable nodes are inflammatory. Bulbomembranous urethral cancer in particular spreads to the urogenital diaphragm, prostate, perineum, and scrotum. Hematogenous spread is rare except in advanced disease and in primary transitional cell carcinoma of the prostatic urethra.

Evaluation and Staging

The 2010 American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) staging system8 is based on the depth of invasion of the primary tumor and the presence or absence of regional lymph node involvement and distant metastasis (Table 43.1). The 2010 AJCC system subdivides T1 lesions into T1a (no lymphovascular invasion or poorly differentiated tumors) and T1b (the presence of lymphovascular invasion or poorly differentiated histology); prostatic invasion is now reclassified as T4 disease (previously T3). Examination under anesthesia is useful to evaluate the local extent of disease. Cystoscopy and transurethral or needle biopsy of the lesion, and of the prostate if indicated, are also performed at the time of examination under anesthesia. A complete blood count and serum chemistry analysis coupled with urine culture and cytology are routinely obtained. Cytology is particularly helpful in patients with transitional cell carcinoma. A computed tomography (CT) scan with contrast is useful in local staging with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan with gadolinium the ideal staging modality for evaluating local soft tissue, lymph node, and bone involvement.9

Treatment

Surgery is the mainstay of treatment of carcinoma of the male urethra. In general, anterior urethral cancers are more amenable to surgical extirpation, and the prognosis is better than that of posterior urethral tumors, which are more often associated with extensive local invasion and distant metastasis.10 Radiation therapy is reserved for patients with early-stage lesions of the anterior urethra who refuse surgery. Although it preserves the penis, radiation may cause urethral stricture or chronic penile edema and may not prevent new tumor occurrence. Multimodal treatment combining chemotherapy and radiation therapy with surgical excision for locally advanced urethral carcinomas has yielded promising results (disease-free survival 60% in one series).11 The median survival without treatment or with palliation is approximately 3 months.

Site-Specific Treatment

Carcinoma of the Distal Urethra. Superficial tumors (Ta, Tis, and T1) are usually treated with transurethral resection and fulguration with close follow-up. Tumors invading the corpus

spongiosum (T2) and localized to the distal half of the penis are best treated with a partial penile amputation with a 2-cm margin proximal to the visible or palpable tumor. If infiltrating tumor is confined to the proximal penile urethra or involves the entire urethra, total penectomy is indicated. Isolated reports of penile-sparing surgery (urethrectomy with corpora cavernosa sparing) have a high incidence of failure.12 Ilioinguinal node dissection is indicated only in the presence of palpable adenopathy. Prophylactic groin dissection has no proven role in this site.

spongiosum (T2) and localized to the distal half of the penis are best treated with a partial penile amputation with a 2-cm margin proximal to the visible or palpable tumor. If infiltrating tumor is confined to the proximal penile urethra or involves the entire urethra, total penectomy is indicated. Isolated reports of penile-sparing surgery (urethrectomy with corpora cavernosa sparing) have a high incidence of failure.12 Ilioinguinal node dissection is indicated only in the presence of palpable adenopathy. Prophylactic groin dissection has no proven role in this site.

TABLE 43.1 American Joint Committee on Cancer Tumor, Node, Metastasis Classification System for Urethral Cancer | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Carcinoma of the Bulbomembranous Urethra. Early superficial tumors (Ta, Tis, and T1) can be treated with transurethral fulguration or segmental resection with end-to-end anastomosis; however, such cases are rare. Invasive tumors (T2, T3) are best treated with radical cystoprostatectomy with en bloc penectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy. Despite this aggressive approach, the prognosis remains dismal, with a 5-year disease-free survival of 26% in patients with invasive bulbomembranous carcinomas.13 Isolated reports of penile preservation surgery for invasive bulbomembranous cancers have used adjuvant radiation therapy (45 Gy) and concurrent chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and mitomycin C with acceptable results.14

Carcinoma of the Prostatic Urethra. Primary carcinoma arising from the prostatic urethra is rare. Adenocarcinomas and urothelial carcinomas are found. Although superficial lesions (Tis-pu, Tis-pd, T1) can be managed by transurethral resection, such tumors are rare. Invasive urothelial carcinoma of the prostatic stroma (T2) carries a poor prognosis despite aggressive surgical therapy. Extravesical extension of disease has a worse prognosis than intraurethral disease, with a higher chance of nodal involvement and a 5-year survival rate of only 32%.15

Advanced carcinoma (T3-4N1 to N3) of the prostatic urethra is best treated with a combination of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (methotrexate sodium, vinblastine sulfate, doxorubicin hydrochloride [Adriamycin, Pharmacia S.p.A, Milan, Italy], and cisplatin [MVAC]) with consolidative surgery or irradiation. One series of five patients (with T2-4N0M0 lesions) treated with neoadjuvant MVAC chemotherapy had a complete response rate of 60%.16 MVAC chemotherapy preoperatively was ineffective against nonurothelial carcinoma.

Radiation and Multimodal Therapy

Radiation therapy alone has poor results in male urethral carcinoma. Patients who receive radiation therapy followed by salvage surgery seem to fare worse than with surgery in an integrated fashion. The most common approach has been external-beam radiotherapy of 50 to 60 Gy with best results for distal urethral lesions. Multimodal therapy with chemoradiation has shown the efficacy of 5-FU, mitomycin C, and cisplatin with radiation for squamous cell carcinoma of the urethra.17,18

CARCINOMA OF THE FEMALE URETHRA

Carcinoma of the urethra is the only genitourinary neoplasm that is more common in women than in men (four-to-one ratio). The peak incidence is in the sixth decade, more commonly in white women. Chronic irritation, recurrent urinary tract infections, and a host of proliferative lesions (caruncles, papillomas, polyps) are predisposing factors, and HPV may play a role. Leukoplakia of the urethra is considered a premalignant condition. In females, the urethra is approximately 4 cm long, mostly buried in the anterior vaginal wall, and divided into the distal one-third (anterior urethra) and the proximal two-thirds (posterior urethra). The most common presenting symptom (greater than 50%) is urethrorrhagia. Urinary frequency, obstructive voiding, a foul-smelling discharge, and a palpable urethral mass are other modes of presentation. Initially, it may be difficult to distinguish fungating tumors of the urethra from those of the vagina or vulva.

Spread of urethral carcinoma follows the anatomic subdivision: lymphatics of the anterior urethra drain into the superficial and deep inguinal nodes and the posterior urethra into the external iliac, hypogastric, and obturator nodes. At presentation, one-third of patients have inguinal lymph node metastases and 20% have pelvic node involvement. Palpable inguinal nodes in patients with urethral cancer invariably contain metastatic carcinoma. The most common sites of distant spread are the lungs, liver, and bone.19

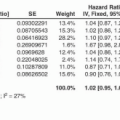

An epidemiologic survey of female urethral cancer identified over 700 women in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database.20 No other study approaches this one in number of patients analyzed. The median overall survival in this large cohort was 42 months, with 5- and 10-year overall survival rates of 43% and 32%, respectively. The median cancer-specific survival was 78 months, and the 5- and 10-year cancer-specific survival was 53% and 46%, respectively. On multivariate analysis of nonmetastatic patients, variables predicting for worse cancerspecific survival were African-American race, stage T3 through T4 tumors, node-positive disease, nonsquamous cell histology, and advanced age.

Pathology

Stratified squamous epithelium lines the distal two-thirds of the female urethra, and transitional epithelium (urothelium) lines the proximal one-third. The majority (60%) of neoplasms of the female urethra are squamous cell carcinomas. Less common types are urothelial carcinoma (20%), adenocarcinoma (10%), undifferentiated tumors (8%), and melanoma (2%). Clear cell carcinoma is a distinctive clinical entity that has generated considerable interest with respect to its prognosis and relationship to urethral diverticulae.21 Histology does not affect the prognosis, and all are treated similarly. In general, anterior urethral carcinomas are low grade and stage; carcinomas involving the proximal or entire urethra are of a higher grade and stage.

Evaluation and Staging

The workup for women with suspected urethral carcinoma includes a pelvic examination under anesthesia, cystourethroscopy, and biopsy. Radiographic evaluation includes a chest x-ray and CT of the pelvis and abdomen. MRI is particularly useful for staging of female urethral carcinoma. Although the 2010 AJCC TNM staging includes female urethral cancer,8 the practical usefulness is limited. Clinically, it is more useful to stage, treat, and prognosticate female urethral cancers by stratifying patients based on anatomic location (anterior versus posterior urethra versus entire urethra) and clinical stage (low stage versus high stage).22

Treatment

The anatomic location and stage of the tumor are the most significant prognostic factors predicting local control and survival. Treatment is based on the stage at the time of initial presentation, with low-stage distal urethral tumors having a better prognosis than high-stage proximal urethral tumors. In one series, the 5-year disease-specific survival was 46%, with 89% survival for low-stage tumors and 33% for high-stage disease.23

Local surgical excision is often sufficient in selected patients with low-stage distal urethra carcinoma. With proximal urethra and for bulky locally advanced tumors, more aggressive treatment with an anterior pelvic exenteration is often needed (en bloc total urethrectomy, cystectomy, pelvic lymphadenectomy, hysterectomy with salpingectomy, removal of the anterior vaginal wall). Bulky proximal urethral tumors that invade the pubic symphysis may require resection of the pubic symphysis and inferior rami. Anterior exenteration alone has been reported to produce a 5-year survival rate of <20% in patients with invasive carcinoma of the female urethra.24 Radiation therapy (brachytherapy alone or with external-beam radiation) is an alternative to surgery in low-stage urethral carcinoma with cure rates up to 75%. The reported doses have ranged from 50 to 60 Gy for brachytherapy alone and 40 to 45 Gy external-beam radiation to the whole pelvis followed by a brachytherapy boost of 20 to 25 Gy over 2 to 3 days. Proximal urethral tumors with bladder neck invasion and bulky tumors require combined external-beam and brachytherapy. Large primary tumor bulk and treatment with external radiation alone (no brachytherapy) were independent adverse prognostic factors. Brachytherapy reduced the risk of local recurrence, possibly as a result of the higher radiation dose.25 Complications from radiation therapy occur in about 20% and include urethral strictures and stenosis, urethrovaginal fistulas, incontinence, and bowel obstruction.

Combined modality treatment with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and preoperative radiation therapy, followed by surgery, is recommended for advanced female urethral carcinoma. A 55% survival rate has been reported with advanced urethral carcinoma treated with radiotherapy plus surgery, as compared with a rate of 34% with radiation alone.26 Although long-term results from multimodal therapy are not yet available, combination chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery is believed essential for local control and cure with larger or locally advanced urethral cancer.23 The prognosis for women with carcinoma of the urethra is poor, regardless of the treatment modality used, and the median time to local recurrence for invasive carcinoma is 13 months.

Distal Urethral Carcinoma

Small superficial (Ta, Tis, and T1) tumors of the distal female urethra can be removed surgically with little risk of urinary incontinence. Spatulation of the urethra and approximation to the adjacent vagina preserve urinary continence and prevent meatal stenosis. For small invasive tumors of the distal urethra (T2), brachytherapy alone is an excellent therapeutic option.

Proximal Urethral Carcinoma

Proximal female urethral carcinomas tend to be more aggressive and bulky. For advanced (T3 and T4) lesions, a multimodal approach is preferred. Surgery consists of a radical cystourethrectomy or an anterior exenteration, depending on the extent of the disease. Radiation therapy with a combination of brachytherapy and external-beam irradiation is usually required. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy with 5-FU and mitomycin C has been noted to enhance the therapeutic ratio of radiation therapy.

CANCER OF THE PENIS

Carcinoma of the penis is an uncommon malignancy in Western countries, representing 0.4% of male malignancies and 3.0% of all genitourinary cancers. Penile cancer constitutes a major health problem in many countries in Asia, Africa, and South America, where it may comprise up to 10% of all malignancies. The incidence of penile cancer has been declining in many countries, partly because of increased attention to personal hygiene.27 It most commonly presents in the sixth decade but may occur in men younger than 40 years. Analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database data shows no racial difference in the incidence of penile cancer among African American men and white men, but significant disparities exist in the mortality of invasive penile carcinoma in the United States.28 Significantly lower rates of invasive penile cancer are seen in Asian American men and significantly higher rates are seen in Hispanic American men. Regional and socioeconomic differences are also noted, with higher rates in the southern area of the United States and in lower socioeconomic populations.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree