Cancer of the Urethra

John J. Coen

Anthony H. Russell

Guido Dalbagni

INTRODUCTION

Primary malignancies of the urethra are infrequent, constituting a fraction of 1% of genitourinary malignancies in both men and women. This rarity is the major factor contributing to the lack of standardized assessment and treatment algorithms. Tertiary cancer referral institutions in North America may treat two or three patients annually, and most centers will see fewer. Clinical reports retrospectively detail limited numbers of patients spanning multiple decades during which diagnostic techniques and management philosophies have evolved rather than remained static.

As a consequence of the diversity of histologic types, the spectrum of clinical stage at presentation, and the heterogeneity of the patient population afflicted with these rare neoplasms, it is clearly imprudent to advocate rigid treatment algorithms and nearly impossible to compare survival outcomes from different therapeutic modalities or combinations of modalities.

In the absence of compelling prospective data, treatment inevitably represents some measure of extrapolation from general principles of oncologic management tailored on the basis of histology, tumor location and extent, and the constraining comorbidities of an individual patient.

Despite the considerably shorter length of the female urethra, female urethral cancer is approximately threefold more prevalent than male urethral cancer. Median age for both men and women is approximately 60 years, with reported cases including teenagers and nonagenarians.

ETIOLOGY

No definitive etiologic factors have been identified in the pathogenesis of epithelial tumors of the female urethra. Etiologic factors in the development of transitional and squamous malignancies of the bladder urothelium are believed to be common to the development of these cell types in the posterior (proximal) urethra. Urothelial neoplasms of the bladder may precede, follow, or, rarely, be detected synchronously with urethral tumors, suggesting “field cancerization” in some patients. Chronic inflammation and infection have been associated with urethral cancer, but no clear linkage has been established. Presence of oncogenic genotypes of human papillomavirus (HPV) (types 16 and 18) has been documented in 59% of cases in one series with HPV limited to squamous and transitional cancers and not found in adenocarcinomas (1). Malignancies in women may arise in urethral diverticula, particularly clear cell carcinomas, prompting the speculation that focal urinary stasis may contribute to the initiation of malignancy in some patients.

In men, no definitive etiologic factors have been identified; however, chronic inflammation seems to play a significant role in the development of carcinoma of the urethra. Urethral strictures have been reported in 25% to 70% of patients, sexually transmitted diseases in 24% to 37% of patients, and trauma in 7% to 10% of patients (2,3,4,5). Herpes simplex virus has been associated with carcinoma of the urethra (6), and HPV type 16 may play a role in the development of carcinoma of the pendulous urethra (7,8).

ANATOMY

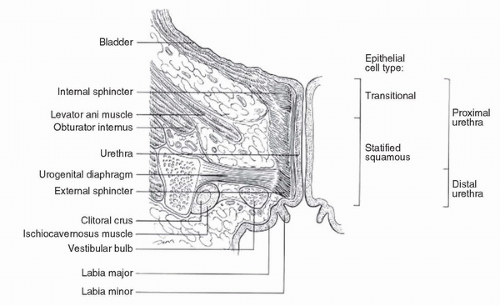

The female urethra (Fig. 54.1) is variable in length (2-6 cm), but 3 to 4 cm is the average. Transitional epithelium lines the proximal third of the urethra, with the distal two thirds lined by squamous epithelium. Surrounding the urethra are the paraurethral glands and ducts (Skene glands) that are the female homolog of the prostate gland. The muscular wall of the urethra has an inner longitudinal layer and outer circular layers continuous with the bladder detrusor. Except during micturition, the lumen is a virtual space. Arterial supply is from the branches of the pudendal artery.

Lymphatic drainage of the distal third or anterior urethra, distal vagina, and anterior vulva is to the medial, superficial inguinal nodes. Subsequent lymphatic flow is to nodes deep in the cribriform fascia and then under the inguinal ligaments to the caudal external iliac nodes. From the proximal two thirds of the urethra and the proximal vagina, lymphatic flow is to the obturator, hypogastric, and external iliac nodes. However, there are no discrete boundaries between these lymphatic drainage basins, and the lymphatic net is rich with interconnections. Additionally, normal lymphatic drainage patterns may be distorted or blocked by the presence of disease. When planning a treatment strategy for an individual patient, it is prudent to assess both the inguinofemoral and pelvic nodal chains, particularly in patients with locally extensive disease, and to consider therapy that will address both potential avenues of lymphatic dissemination.

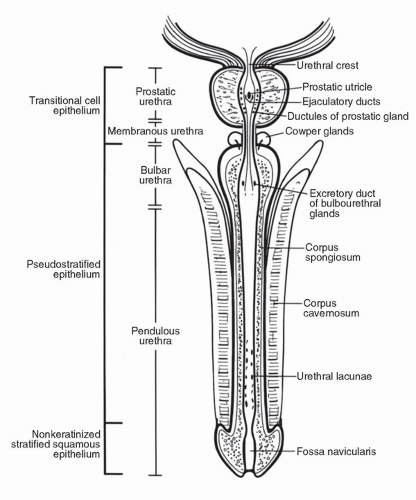

The urethra in men can be divided anatomically into three parts: prostatic, membranous, and penile (spongiose) (Fig. 54.2). The prostatic urethra is approximately 3 to 4 cm long. It begins at the internal urethral orifice located in the bladder neck and extends the entire length of the prostate to the prostatic apex. Within the prostatic urethra is the urethral crest, an elevation of the mucous membrane. The ejaculatory ducts open on each side of the prostatic utricle, a slitlike opening located on an elevation called the colliculus seminalis (verumontanum) in the middle of the urethral crest (9). The urethral crest is flanked on both sides by a depression called the prostatic sinus, the floor of which is perforated by the prostatic ducts. The membranous urethra is the shortest portion, measuring only 1 cm in length. It goes from the apex of the prostate to the bulb of the penis, traversing through the musculature of the urethral sphincter and inferior fascia of the urogenital diaphragm. One small bulbourethral gland (Cowper gland) is located on either side of this portion of the urethra (9). The penile (spongiose) urethra is the longest segment, measuring approximately 15 cm and extending from the distal surface of the urogenital diaphragm to urethral orifice in the glans penis. The penile urethra can be further subdivided into the bulbous and pendulous urethra. The bulbourethral glands open on the lateral surfaces of the bulbous portion of the penile urethra. The penile urethra is surrounded by the corpus spongiosum along its entire length.

The membranous and prostatic urethra make up the posterior urethra, and the bulbous and pendulous portion of the penile urethra make up the anterior urethra. However, clinically and pathologically, the bulbous segment of the penile urethra is included in the posterior urethra as a result of a similar

prognosis for carcinoma in the bulbous and membranous urethra, whereas only the pendulous segment of the penile urethra is referred to as the anterior urethra.

prognosis for carcinoma in the bulbous and membranous urethra, whereas only the pendulous segment of the penile urethra is referred to as the anterior urethra.

The lining epithelium is derived from endoderm of the urogenital sinus except distally in the area of the fossa navicularis, the epithelial lining of which is formed by canalization of ectodermal cells extending into the glans from its tip. The type of epithelium lining the prostatic urethra is of the transitional cell type as far as the ejaculatory ducts, then of the pseudostratified columnar epithelium along the membranous and most of the penile urethra, and nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium near the external urethral orifice

(9,10). This epithelial lining corresponds to a healthy urethra, whereas in the diseased state, or after instrumentation, metaplastic changes can be noted.

(9,10). This epithelial lining corresponds to a healthy urethra, whereas in the diseased state, or after instrumentation, metaplastic changes can be noted.

The lymphatic drainages of the urethra and of the penis are closely interconnected. One or more major collecting trunks that receive the lymphatic drainage from the glans and the pendulous urethra run with the deep dorsal vein and drain into a presymphyseal plexus. Two or more trunks drain from this plexus into the inguinal nodes and occasionally into the external iliac nodes (11). The bulbous segment of the penile urethra and the membranous urethra drain into the external iliac nodes. The lymphatic drainage of the prostatic urethra follows one of the three routes. The first is along the prostatic artery to the obturator and internal iliac nodes, the second is with lymphatics over the seminal vesicle to the external iliac nodes, and the third is from the posterior part of the prostate to the sacral nodes (11).

SYMPTOMS

In women, urinary frequency and dysuria are common. Erratic bleeding will occur in most patients. Obstructive symptoms may progress to urinary retention in some patients. Extension to the vulva may result in pain, pruritus, and inflammation. Erosion into the vagina with ulceration may result in foulsmelling vaginal discharge. Proximal lesions extending to the bladder neck and upper vagina can result in formation of a vesicovaginal fistula with incontinence. Only rarely are urethral cancers diagnosed by surveillance physical examination in asymptomatic patients. Ninety-eight percent of patients are symptomatic at the time of diagnosis, with a median interval of 4.5 months between onset of symptoms and diagnosis (12).

The diagnosis of carcinoma of the male urethra is often delayed, as a result of the nonspecific nature of the symptoms. The median interval from the onset of symptoms to diagnosis has been reported to be 7.5 months (3). The most common mode of presentation is obstructive urinary symptoms, followed by a perineal mass (2,3,13,14). Patients may also present with an abscess, a fistula, hematuria, spotting, irritative symptoms, urethral discharge, or pain. New onset of a urethral stricture in a middle-aged man who has not undergone prior urethral instrumentation should arouse a suspicion of malignancy and should be thoroughly investigated. Rare cases of carcinoma of the male urethra with hypercalcemia have been reported (15,16).

PATHOLOGY

Urethral neoplasms in women and men are both histopathologically different as well as somewhat different in clinical behavior, phenomena attributed to differences between the sexes in normal anatomy and the histology of the urethra (17).

In women, transitional epithelium lines the proximal third of the urethra, and squamous epithelium the distal two thirds. These areas give rise to carcinomas morphologically derivative from those epithelial cell lines, which, in aggregate, account for approximately 80% of primary urethral tumors in women. Squamous carcinomas constitute most primary urethral tumors in women, comprising from 50% to 65% of cases in clinical series (18,19,20). Transitional cell cancers comprise approximately 15% of cases (12,19).

Adenocarcinomas account for 10% to 12% of primary female urethral neoplasms (17,19), but may account for 35% to 57% of cases in referral institutions (12,21). The submucosa of the urethra contains periurethral glands (Skene glands) that are the female homolog to prostatic ductal and glandular tissue in the male. The ducts are lined by pseudostratified and stratified columnar epithelium in which may be found intraepithelial mucous-secreting glands. Skene glands give rise to adenocarcinomas morphologically similar to prostate cancer that may stain immunohistochemically for prostate-specific antigen (PSA) and prostate-specific acid phosphatase (PSAP), and occasionally may produce serologically detectable levels of PSA (22).

Clear cell adenocarcinomas of the urethra characteristically originate in urethral diverticula and are morphologically similar to clear cell adenocarcinomas arising from Mullerian tissues elsewhere in the female genitourinary tract, including the ovaries, fallopian tubes, endometrium, and foci of malignant degeneration in endometriosis. Clear cell cancers comprise approximately 40% of adenocarcinomas of the urethra (23). These generally do not stain for PSA or PSAP (24), although a rare instance has been reported of such staining properties. Immunoreactivity for cancer-associated antigen 125 (CA-125) has been reported for this cell type (25).

Other primary urethral adenocarcinomas include mucinous/columnar or colloid cancers that resemble primary colorectal or endometrial cancers and that may stain positively for carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) (26) and signet ring cell adenocarcinomas.

Cancers with neuroendocrine features including carcinoid and small cell cancers are anecdotally seen. Carcinosarcoma, plasmacytoma, and Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma have been reported as primary within the urethra. In general, management of rare histologic types of urethral neoplasia more commonly associated with other anatomic structures (neuroendocrine tumors, plasmacytoma, lymphoma) will be predicated on the histology rather than the anatomic location of origin and will parallel management of these cell lines diagnosed at other primary sites.

Malignant melanoma can be primary in the female urethra, and may be amelanotic in approximately 20% of instances (27). Therapy is generally surgical because of the relative insensitivity of melanoma to radiation and cytotoxic chemotherapy. Often more deeply invasive than cutaneous melanoma, possibly as a result of delayed diagnosis, prognosis for these lesions is grim, with a propensity to fail rapidly after surgical therapy with local recurrence, regional nodal spread, and hematogenous dissemination (28).

In men, squamous cell carcinoma is the predominant histologic type, representing 50% to 90% of all urethral tumors (2,3,13,14,29,30,31). Transitional cell carcinoma is the second most common histologic type, followed by adenocarcinoma. The histology of tumors originating in the urethra tends to coincide with the morphology of the urothelial lining: tumors originating in the prostatic urethra are transitional cell carcinomas, whereas tumors originating in the penile urethra are squamous in origin. However, there have been numerous reports of transitional cell carcinoma originating in the pendulous urethra (32,33,34,35,36,37), which could be explained by urothelial metaplasia.

Adenocarcinoma may arise from the surface mucosa through a process of metaplasia or from periurethral glands. The possibility of direct extension from rectal adenocarcinoma should be considered. Stage for stage, adenocarcinomas in men have the same prognosis as primary tumors of other histologies.

Sixty percent of tumors originate in the membranous urethra and bulbous portion of the penile urethra (bulbomembranous urethra), 30% in the pendulous segment of the penile urethra, and 10% in the prostatic urethra (3,4,5,14,38).

Cowper glands are small mucous tubuloalveolar bulbourethral glands located on either side of the membranous urethra (9) (Fig. 54.2). They drain through separate excretory ducts in the bulbous urethra after traversing the corpus spongiosum. Cowper glands are the homolog of Bartholin glands in

women. However, pathologic conditions such as infections or carcinoma associated with Cowper glands are much less common than those associated with Bartholin glands (39). This might reflect the difficulty in making an early diagnosis because of the inaccessible location and lack of early clinical symptoms.

women. However, pathologic conditions such as infections or carcinoma associated with Cowper glands are much less common than those associated with Bartholin glands (39). This might reflect the difficulty in making an early diagnosis because of the inaccessible location and lack of early clinical symptoms.

Documented cases of adenocarcinoma of Cowper glands are extremely rare. The patients’ ages have ranged from 19 to 70 years. Patients present with perineal pain, lower urinary tract symptoms, and a mass in the perineum (39,40,41,42,43). The tumors have a tendency for local invasion and less propensity for metastasis (40,41,43). Microscopically, these neoplasms share many of the features with adenocarcinomas arising from the urethral surface mucosa. The patients have been managed either by local resection (39) or by radical excision (42) with and without radiation. Local control has been achieved in a few patients, with most progressing locally with or without metastatic sites within a short period of time. The prognosis is poor with no documented survivors beyond 5 years.

Adenoid cystic carcinoma, morphologically similar to similar tumors arising in major and minor salivary glands and Bartholin glands, has been reported arising in Cowper glands with anecdotal long-term survival after combined modality therapy (44).

EVALUATION AND STAGING

In women, as a consequence to the accessibility to examination, there can be no substitute for the information gleaned by obtaining a history and performing a careful physical examination. If radiation therapy is to be employed as all or a component of treatment, the status and underlying health of adjacent normal tissues including the vagina, cervix, uterus, pelvic bones and femurs, major vessels, and anorectum should be ascertained. Physical examination, possibly including examination under anesthesia, will yield information regarding both tumor extent and the status of adjacent vulnerable normal tissues that is beyond the capability of the most sensitive imaging techniques. Imaging should be appreciated as complementary to physical examination and should be used to assess disease extent beyond the limits of direct visualization and palpation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree