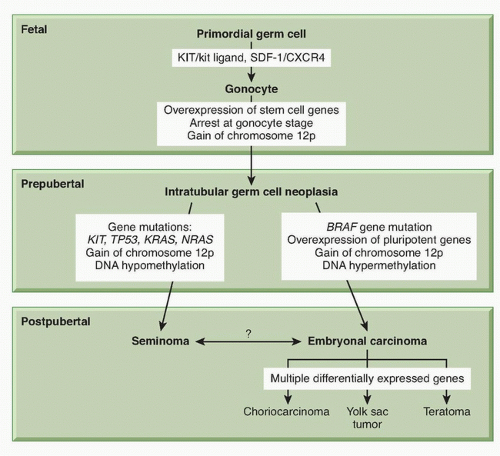

Mechanism of Germ Cell Transformation

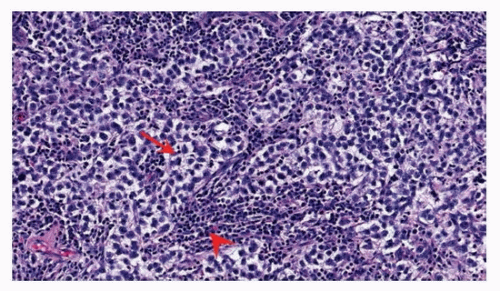

ITGCN is thought to derive from malignant transformation of primordial germ cells or gonocytes during fetal development.

31 Primordial germ cells migrate from the proximal epiblast (yolk sac) through the hindgut and mesentery to the genital ridge, and become gonocytes. The precise molecular events underlying transformation to ITGCN are not well understood. The most consistent genetic finding in germ cell tumors is a gain of material from chromosome 12p. The majority of NSGCT and seminomas contain i(12p), an isochromosome comprised of two fused short arms of chromosome 12. The remaining i(12p)-negative germ cell tumors also have a gain of 12p sequences in the form of tandem duplications that may be transposed elsewhere in the genome.

Gain of 12p sequences has been found in ITGCN, indicating that it is an early event in testicular cancer pathogenesis. The acquisition of i(12p) is not thought to be the initiating event, however, because it is preceded by polyploidization.

32 Overexpressed genes on 12p are likely to be important, and there are candidate genes on 12p including several that confer growth advantage (

KRAS2,

CCND2 [cyclin D2]), and others that establish or maintain the stem cell phenotype (

NANOG,

DPPA3,

GDF3). The exact genes that are critical to this step have not yet been identified.

Seminomas are usually hypertriploid, whereas NSGCT is more commonly hypotriploid.

33 Other chromosome regions were found to have nonrandom gains or losses in germ cell tumors with less frequency than 12p. Single gene mutations are uncommon in germ cell tumors. The most commonly mutated genes are

BRAF,

KIT,

KRAS,

NRAS, and

TP53.

11 The KIT/kit ligand (

KITLG) pathway

has special relevance for gonadal development. The biologic function of this pathway is broad and includes development of hematopoietic cells, melanocytes, and germ cells.

34 KITLG is essential for primordial germ cell survival and motility, as are the chemokine

SDF-1 (CXCL12) and its receptor CXCR4.

11 Immunohistochemical markers found on primordial germ cells and gonocytes (PLAP, CD117 [

KIT], OCT3/4 [

POU5F1]) are also found on ITGCN, suggesting a transformation from these cells during fetal development (

Fig. 44.4). The biallelic expression of imprinted genes in germ cell tumors has been reported, showing that they likely arose from primordial germ cells where the genomic imprinting is temporarily erased.

31Somatic mutations in

KIT as well as increased copy number have been described in 9% of testicular germ cell tumors and 20% of seminomas.

4 The somatic alterations in

KIT found in germ cell tumors are predicted to upregulate pathway activity.

KITLG plays a role in determining skin pigmentation and has undergone strong selection in European and Asian populations. Difference in the frequency of risk alleles for

KITLG between European and African populations may provide an explanation for the difference in germ cell tumor incidence between Caucasian and African Americans.

There is evidence that epigenetic regulation of gene expression plays a role in the pathogenesis of germ cell tumors. The DNA methylation patterns are different among histologic types. Global hypomethylation is more common in seminomas than in NSGCT.

31 In a study of 16 germ cell tumors, the methylation of CpG islands in NSGCT was similar to that observed in other tumor types, whereas it was virtually absent in seminomas.

35 Aberrant promoter methylation is generally associated with absent or downregulated expression of the methylated genes. This can result, for example, in the silencing of tumor suppressor genes.

31 Methylation has also been correlated with germ cell tumor differentiation. The more differentiated tumors (yolk sac tumor, choriocarcinoma, teratoma) were consistently hypermethylated, whereas seminoma and ITGCN were hypomethylated.

36 Some of the observed methylation patterns may reflect normal development rather than germ cell tumor pathogenesis.

Pluripotency of Embryonal-Like Differentiation in Germ Cell Tumors

Embryonal carcinoma has a six-gene signature (

DNMT3B,

DPPA4,

GAL,

GPC4,

POU5F1,

TERF1), which was detected in three of five independent studies.

11 All six of these genes are involved in establishing and maintaining pluripotency.

SOX2 encodes a transcription factor essential for maintaining self-renewal of embryonic stem cells and is upregulated in embryonal carcinoma. Two additional genes that encode transcription factors associated with stem cell pluripotency,

NANOG and

POU5F1, are upregulated in both seminoma and embyronal carcinoma.

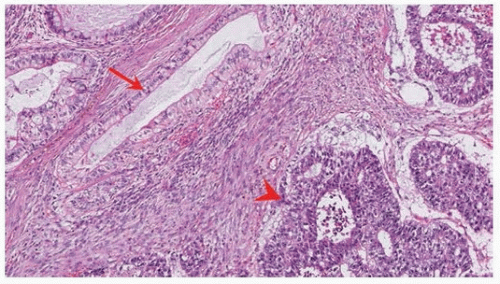

26 Lineage differentiation takes place in NSGCT, mimicking the development of a normal zygote. Thus, embryonal carcinoma can be thought of as the transformed counterpart of embryonic stem cells, displaying self-renewal, pluripotency, and lineage differentiation.

Familial Predisposition to Germ Cell Tumors

Approximately 1.4% of patients with newly diagnosed germ cell tumor report a family history of germ cell tumor.

34 First-degree male relatives of patients with testicular cancer have a 6- to 10-fold increased risk of developing testicular cancer. These observations point to the likely existence of a hereditary germ cell tumor subset. The inheritable effect is mild, and the most common number of affected relatives in a family is two. The age at diagnosis among familial cases is 2 to 3 years younger than sporadic cases, and there is a higher incidence of bilateral tumors.

The gr/gr deletion on chromosome Y, common among infertility patients and associated with a two- to threefold increased risk of testicular cancer, was studied as a candidate region for hereditary risk.

4 The frequency of gr/gr variant is low, however, such that it could only account for a small component of hereditary risk. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) for testicular cancer have been hampered by relatively small sample sizes. Nevertheless, five loci of interest were identified in a GWAS study from the

United Kingdom, on chromosomes 1, 4, 5q31.3, 6, and 12p22, including confirmatory data for the chromosome 6 locus. The single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) associations on chromosomes 1 and 4 were not convincingly replicated in an independent US study, whereas the associations on chromosomes 5 and 12 were confirmed. The strongest associated SNPs were at 12q22 within the

KITLG gene, for which there is a >2.5 risk of disease per major allele. For the chromosome 5 and 6 loci, a 1.5-fold increased risk was identified per major allele. The loci on chromosome 5 implicate the gene

SPRY4, which encodes an inhibitor of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. The locus on chromosome 6 falls within the intron of

BAK1, which promotes apoptosis. The location of a disease-associated SNP near or within a gene does not definitively implicate that gene, yet all three of the genes identified in GWASs are directly or indirectly associated with the KIT/KITLG pathway.

11 These genes may be responsible for an estimated 15% of genetic predisposition to germ cell tumors, whereas the genetic basis of the other 85% of familial aggregations remains unexplained.

Cisplatin Sensitivity and Acquired Resistance in Adult Germ Cell Tumors

Exquisite sensitivity to chemotherapy distinguishes germ cell tumors from most other cancers. Levels of p53 protein are elevated in all germ cell tumors except teratoma.

31 To maintain genomic integrity, embryonic stem cells have a high sensitivity to DNA damage, suggesting that the high levels of wild-type p53 seen in germ cell tumors may be intrinsic to their germ cell nature.

TP53 gene mutations are uncommon in germ cell tumors, however, and the role of acquired

TP53 mutations in the emergence of chemotherapy resistance has not been established.

11 Moreover, levels of p53 protein assessed by immunohistochemistry were not associated with outcome. While mutations in

TP53 have been observed in about 7% of seminomas, its significance in germ cell tumors remains unclear.

Mutations of

BRAF including V600E mutations have been detected in a small percentage of NSGCT.

BRAF mutations were most prevalent in mediastinal primary tumors, late relapse, and cisplatin-resistant NSGCT, suggesting a role in chemoresistance. Further study is needed to define the prognostic significance of

BRAF mutation and whether the V600E mutation can be therapeutically targeted. A high ratio of proapoptotic Bax to antiapoptotic Bcl-2 was found in invasive germ cell tumors and may explain the rapid apoptotic response to DNA-damaging drugs; however, the Bax:Bcl-2 ratio was not associated with treatment outcome.

31 Finally, the emergence of cisplatin resistance may be intimately associated with the expression of genes and pathways responsible for lineage differentiation in NSGCT, in other words, intrinsic to the germ cell biology rather than the result of specific mutations.