Chapter Outline

Plain Language Summary 2

History 2

History of the Breast 2

History of Medical Screening 4

History of Screening With Breast Self-Exam and Clinical Breast Exam 5

History of Mammography Screening 6

History of the Media and Marketing Related to Breast Cancer Screening 7

History of Science on Breast Cancer Screening 8

The Accumulation of Evidence on the Benefits 8

The Accumulation of Scientific Evidence on Potential Harms 10

History of Variability in Guideline Recommendations and Quality 13

History of Informed Medical Decision Making 15

History of Patient Activism, Politics, and Law in Screening 16

Methods to Identify High-Risk Women for Screening 18

Studying Rapidly Evolving New Technologies and Our General Technophilia 21

Thoughts on the Future 22

Conclusion 22

Glossary 23

List of Acronyms and Abbreviations 24

References

Plain Language Summary

Culture, politics, money, and media intersect to influence the interpretation of scientific evidence, directly affecting the lives of women. Before venturing into detailed chapters reviewing the scientific evidence on breast cancer screening, we begin this textbook with an overview of the history of the breast, of breast cancer screening, and of the perfect storm of politics and science surrounding this topic. We examine the complex forces that shape the way many well-intentioned individuals view the same scientific evidence, yet arrive at vastly different interpretations.

This chapter provides a brief overview on the history of the breast, breast cancer screening, scientific evidence for and against different screening strategies, and important influences on the development of screening strategies.

History

History of the Breast

Over the years, well-intentioned individuals have reviewed the scientific evidence on breast cancer screening, yet come to surprisingly different conclusions. While many chapters in this textbook describe the scientific evidence surrounding breast cancer screening dating back decades, the interpretation of this evidence is influenced by complex factors. Individual interpretation of scientific medical information is colored by a heightened fear of breast cancer, mass media campaigns promoting screening, political involvement, and financial incentives all colliding with the complicated culture that surrounds women’s health in general, and breast health in particular. While a financial conflict of interest might be concrete and obvious, an emotional conflict of interest is subtle and can be deeply rooted. Just as a Rorschach ink blot might be interpreted quite differently by individuals, the interpretation of scientific evidence remains challenging in the area of breast cancer screening with multiple and variable interpretations.

To understand the complex nature of breast cancer screening scientific data, a reflection on the history of the breast is a helpful starting point. While thousands of pages have been written on this topic, a summary of key themes is briefly covered here.

The breast was depicted in ancient art as a symbol of motherhood, comfort, and nourishment. For example, this ancient Greek sculpture ( Fig. 1.1 ) depicts a mother feeding her twins, with the mother’s right hand gently playing with the foot of one of the infants. The mother seems relaxed in this nurturing context. Sculptor Jean-Jacques Caffieri’s marble statue titled Hope Nourishes Love shows a young woman who represents Hope nursing a winged Cupid, personifying love ( Fig. 1.2 ). Fig. 1.3 depicts Artemis, goddess of the hunt and wild animals, in her temple at Ephesus (in present-day Turkey) with striking rows of pendant objects on her torso. Most scholars have identified these pendant objects as breasts. The nourishing breast is tied to power and strength in this hunter-goddess’s statue. Just as scientists variably interpret medical data, the interpretation of art has varied over the years. While most assume that the repeated paired objects on this statue are breasts, a scientist in 1978 claimed that, as no nipples were depicted, the round objects represent bulls’ testicles, adding an example of variability in interpretation of visual data based on the viewer’s perspective.

While historic depictions have also sexualized the breast, over the centuries, artistic depictions of the breast became increasingly sensual. Representations of the breast moved from scenes of nourishment between Madonna and Child to increasingly sexualized images. In the last century, the slender flapper image of a woman was replaced with full-bodied women and the breast came to represent a key feature of a woman’s sexuality. Push-up bras and breast augmentation became commonplace and were openly discussed in conversations.

Breast cancer is one of the most feared afflictions in modern society because of its potential devastation of both the woman and her family, given the nurturing, comforting, and sexual attributes of breasts, in addition to the risk of death from the disease. Descriptions of breast cancer treatments date back thousands of years and include the cauterization of breast tumors and ulcers as described in Egyptian textbooks. In describing breast cancer, authors of the past bluntly stated: “There is no treatment.” Thankfully, this is no longer the case. However, early treatments included extensive surgical resections. As the surgical treatments for breast cancer were developed, images of mastectomy scars came to represent mutilation of the body and death. This new symbolism was evident in artist and former fashion model Matuschka’s stunning self-portrait, featured on the cover of The New York Times Magazine in 1993, in which she boldly exposed the remnants of her postmastectomy breast. The juxtaposition of the model’s lithe body and the taboo scar forced readers to confront breast cancer and its raw physical impact.

History of Medical Screening

Given the historical value society has placed on women and the breast, it is no surprise that breast cancer screening remains in the forefront of societal focus. With the development of successful treatment for early-stage breast cancer, early detection screening programs became a possible approach to consider.

Effective medical screening includes consideration of whether earlier treatment of disease improves prognosis and whether screening tests are accurate and able to detect disease at an early stage. Over time, the criteria for evaluating the usefulness and appropriateness of medical screening tests expanded to take into consideration characteristics of the specific disease, such as its severity and frequency in the target population, and characteristics of the screening test, such as cost and acceptability. Additionally, the impact of implementing screening exams in the target health care system became a requirement for consideration as well ( Table 1.1 ).

| Disease requirements |

|

|

|

|

|

| Screening test requirements |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Health care system requirements |

|

|

The success of mass screening programs, such as cervical cancer screening on reducing morbidity and mortality, has been impressive. These successes have increased enthusiasm for the general concept of screening to allow early-stage detection of disease while it is easier to treat. Screening for many diseases has now become a vital part of public health efforts to improve health and health outcomes.

History of Screening With Breast Self-Exam and Clinical Breast Exam

As improved treatment options became available to women with early-stage breast cancers and following the hypothesis that earlier detection saves lives, scientists and health care practitioners set out to identify the best strategies for finding breast cancer early via screening. Initially, a three-pronged approach was formulated involving screening mammography, clinical breast exam, and breast self-exam. The idea behind this comprehensive tactic was that: (1) breast self-exams would keep breast screening at the forefront of a woman’s health care practice and remind her to screen; (2) clinician breast exam would provide a good opportunity for the physician and woman to discuss breast health and screening; and (3) all three tactics would provide a thorough screening that improved the woman’s chance of finding a cancerous lesion early.

From the 1960s through 2000s, clinicians were encouraged to perform screening breast exams on their patients in the clinic, and clinicians instructed their patients in how to perform monthly breast self-examinations. As scientific evidence was collected, however, it became apparent that breast self-examination is not associated with a reduction in breast cancer mortality, though it does increase the risk of having a biopsy with benign results.

Studies of screening clinical breast examination performed by clinicians have been limited. The Canadian National Breast Screening Study found the 25-year cumulative mortality from breast cancer to be similar between women screened with mammography and clinical breast examinations and women screened with clinical breast examinations alone. However, the quality of these exams may have exceeded that of the standard community practice: the clinicians providing clinical breast examinations in the study were well-trained, spent 5–10 minutes examining each breast, and were periodically evaluated for examination quality. In general, clinical breast exams performed in the community setting were noted to have lower sensitivity compared with mammography. A US study found examination sensitivity to be only 21.6% in asymptomatic women who received a clinical breast examination within 1 year of breast cancer diagnosis but died of breast cancer within 15 years of diagnosis.

While the evidence on screening for breast cancer by breast self-examination and clinician breast examination is not covered in this textbook, and less research has been done on these topics, in general they are no longer recommended as part of most breast cancer screening programs in developed countries.

History of Mammography Screening

For many diseases, detection is best achieved through visualization. Initial advances in breast imaging occurred in the early 1900s when Dr Albert Salomon, a German surgeon, began using X-rays to image the breasts of symptomatic women. Mammography exams were initially evaluated as a diagnostic tool and not considered as a screening tool. With technological advances, the first dedicated mammography systems were in place the mid-1960s. As with any new, unproven device these mammography units were initially met with cautious regard by many practicing physicians, including breast surgeons, until their worth as a diagnostic aid was demonstrated.

The use of mammography as a screening tool took shape in the later part of the 1900s. In 1969, R.L. Egan published an article in Cancer describing screening mammography as having a “certain magic appeal” and saying that the patient “feels something special is being done for her.” The availability of a tool to identify early-stage breast cancer in order to improve treatment and survival helped to establish breast cancer screening as a common practice. Women wanted to do anything possible to reduce their risk of dying of breast cancer, and breast cancer screening with mammography was seen as promising.

In the 1960s, breast imaging became a radiology subspecialty in medical schools in the United States, and the Health Improvement Program (HIP) in New York—the first randomized controlled trial (RCT) of screening mammography—began in 1963. In 1972, the results of this HIP trial were published with much fanfare. This study reported a statistically significant reduction in breast cancer mortality among women randomized to the screening mammography arm of the study. This promising result was followed by additional studies including more RCTs (see chapter: Estimates of Screening Benefit: The Randomized Trials of Breast Cancer Screening ), observational studies (see chapter: The Importance of Observational Evidence to Estimate and Monitor Mortality Reduction From Current Breast Cancer Screening ), statistical modeling (see chapter: The Role of Microsimulation Modeling in Evaluating the Outcomes and Effect of Screening ), and even studies designed to identify best ways to promote mammography in different communities. Research on mammography and breast cancer screening in community settings became a primary focus in the early 1990s as the National Cancer Institute (NCI) initiated funding for the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC). The consortium is a collaborative network of multiple, nationwide mammography registries with linkage to cancer registries for the sole purpose of research on breast cancer detection and identification. The BCSC has been in operation since 1994 and has been the source of more than 550 research articles about breast cancer.

History of the Media and Marketing Related to Breast Cancer Screening

Alongside the rapidly growing and extensive body of scientific evidence on breast cancer screening, media messages geared toward women and their families have promoted breast cancer screening. Throughout the past century, a “war on cancer” has been waged. This war initially began as a push to get women to seek evaluation as soon as they noted a breast abnormality. Women’s activism and war rhetoric against breast cancer has been traced back to the Women’s Field Army which was formed in the 1930s to educate the public about breast cancer and encourage women to seek medical attention as soon as they noted a breast abnormality. This war rhetoric soon moved from encouraging diagnostic evaluation to encouraging screening for earlier cancer detection.

Increased interest in diagnostic evaluation and screening has had fiscal ramifications, as breast cancer charities have gained popularity and become a strong political force. Additionally, the massive funding stream into breast cancer research began to flow in the mid-1990s and continues to be a tremendous resource today.

While media attention has helped to inspire charitable contributions toward research and clinical programs, there have been negative results as well. In the media, breast cancer is often characterized as imminently life threatening—the anxiety-fueling “one in eight” statistic—and screening mammography is considered to be the only way to combat the resulting sense of vulnerability. Many misconstrue that one in eight women will die of breast cancer or that one in eight women will be diagnosed with breast cancer in the immediate year ahead. Rather, this is a statistic that one in eight women will be diagnosed with (but not die of) breast cancer in her lifetime. Most of these women will live long lives after their diagnosis with many remaining in remission indefinitely.

In addition to feeding anxiety, media marketing of breast cancer screening has been unbalanced, often covering only the benefits of mammography without discussing the harms and placing blame on and causing guilt in women. Ad campaigns have stated that women who died from breast cancer “could have been saved” had they been screened. Slogans include: “Mammography saves lives, and one of them might be yours,” and “If you haven’t had a mammogram, you need more than your breasts examined.”

The supply of information guiding individual screening decisions extends beyond research and big business; the actions of famous individuals inform and sway the public as well. Awareness of breast cancer being diagnosed in prominent women fueled the breast screening movement through the media. In 1974, Margaretta (Happy) Rockefeller, the wife of former American Vice President Nelson Rockefeller, underwent a double mastectomy 2 weeks after Betty Ford, then First Lady of the United States, underwent the same procedure. It is suspected that the media attention surrounding prominent women such as these led to increased attendance at breast cancer screening programs and the subsequent increase in the incidence of breast cancer cases in the United States.

Prime examples of other prominent women in the media include Amy Robach, an anchor on a US national morning news show, who had a screening mammogram on live television and revealed months later that the mammogram had found breast cancer. Robach’s message to her audience: “If I got the mammogram on air and it saved one life, then it’s all worth it. It never occurred to me that the life would be mine.” There is also former First Lady of the United States Nancy Reagan, who publicly chose mastectomy as her form of breast cancer treatment, which resulted in a subsequent increase in women choosing mastectomy. Finally, in 2013 actress Angelina Jolie Pitt announced her BRCA1 gene mutation status and her decision to undergo prophylactic mastectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Jolie Pitt encouraged women to make informed decisions, keeping their own health histories in mind and knowing the best decision for them, not basing their decision on what other people do. Referral to genetics services increased in the months following Jolie Pitt’s news story.

Balanced information is not always included in marketing media. Mammography is now an estimated $8 billion annual business in the United States, with active marketing by hospitals and facilities to entice women to their centers. Such facilities advertise that they are using the most recent technologies, operating under the assumption that new technology is superior to “old” technology.

At what point does marketing overshadow medical reason and evidence? One US hospital promotes monthly “Mingle and Mammograms” parties with pampering to calm the nerves of women before they receive a screening exam. These parties include appetizers, chocolate, foot massages, pink carnations, and bags emblazoned with the phrase “Fight Like a Girl.” In addition to appetizers, women would benefit from digestible information that will aid them in making informed medical decisions about their own participation in screening. Women need balanced information on potential harms and benefits of screening .

History of Science on Breast Cancer Screening

A primary area of focus in this book is a comprehensive review of the evidence demonstrating the potential benefits and harms of breast cancer screening. Estimates of Screening Benefit: The Randomized Trials of Breast Cancer Screening, Weighing the Benefits and Harms: Screening Mammography in the Balance, The Importance of Observational Evidence to Estimate and Monitor Mortality Reduction From Current Breast Cancer Screening, The Role of Microsimulation Modeling in Evaluating the Outcomes and Effect of Screening, Challenges in Understanding and Quantifying Over-Diagnosis and Over-Treatment provide an in-depth examination of the scientific evidence produced to date showing the benefits and harms of different screening strategies. Below is a brief summary providing the historical background for the chapters that follow in this text.

The Accumulation of Evidence on the Benefits

The gold standard study design to evaluate cancer screening is the RCT. The first RCT about mammography, the HIP trial, was initiated in New York in 1963. The study reported positive results in women 50–69 years of age suggesting that mammography screening is effective in reducing breast cancer mortality. These promising results encouraged many physicians and health plans to begin offering mammography screening to the general public. The HIP trial also encouraged scientists to conduct other RCTs to verify the findings. The early reports of these other RCTs were generally positive—screening women with mammography was associated with a statistically significant reduction in subsequent breast cancer mortality. Chapter “Estimates of Screening Benefit: The Randomized Trials of Breast Cancer Screening” provides a comprehensive review of breast screening RCTs.

These large, expensive RCTs collectively followed hundreds of thousands of women over many years of screening with additional follow-up over the ensuing decades to collect mortality data. It was challenging to get all of the women to comply with the screening intervention, with compliance rates of about 80%. Additionally, as the news spread that breast cancer screening was possibly beneficial, it was also increasingly challenging to conduct a trial in which women randomized to the control arm did not seek out and receive mammography. Some RCTs reported that approximately 20–30% of women in the control arm received screening mammography. The screening programs varied among these RCTs in numerous other ways, such as the number of screening images per breast, the time interval between screens, and the age of women entering into the screening program.

As more RCTs were completed, some RCTs did not reach statistical significance, especially in subgroup analyses. As the quality of these trials was extensively reviewed, heated arguments ensued, helping to push the development of systematic reviews and meta-analysis. Scientists were able to employ techniques of meta-analysis to merge together the data to assess overall impact on a larger scale. One great challenge of studying breast cancer screening is the fact that breast cancer is not as common as many think, and a large number of women are required to participate in these trials to adequately assess an impact. This challenge is particularly pertinent when evaluating subgroups, such as examining the impact of screening on women in certain risk or age groups. As the overall number of meta-analyses performed has grown, even these meta-analyses have produced conflicting results (see Estimates of Screening Benefit: The Randomized Trials of Breast Cancer Screening, Weighing the Benefits and Harms: Screening Mammography in the Balance ). Different methods have been used over time, including the underlying inclusion and exclusion of trials in the analyses, which obviously has a major impact on the overall findings.

Given the cost and time required for RCTs, and as breast cancer screening became a standard of care in clinical practice in many countries, RCTs became unfeasible. Scientists then turned to other study designs. Case-control studies evaluated mortality differences between screened and unscreened women, but these studies were tricky methodologically, with many potential sources of bias. The selection of cases, controls, and definitions of “screening” varied among these case-control studies, as did their results.

Scientists have increasingly evaluated the accuracy of mammography using secondary outcomes rather than its impact on mortality. As large populations underwent screening, observational and ecological data became available. In the United States, the BCSC provided a wealth of standardized data. Other countries evaluated the impact of screening on their entire population of women who participated in standardized programs (see chapter: The Importance of Observational Evidence to Estimate and Monitor Mortality Reduction From Current Breast Cancer Screening ).

With this proliferation of big data, methods of statistical modeling were developed (see chapter: The Role of Microsimulation Modeling in Evaluating the Outcomes and Effect of Screening ). Unfortunately, these statistical models rely on many underlying assumptions that remain uncertain, such as the amount of time it takes lesions to progress from atypia to ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) to invasive breast cancer. As we wade into the scientific literature using statistical modeling to evaluate whether screening has a positive impact on mortality, it is unclear if the bottom of this pool of data lies within inches or miles of our feet ( Fig. 1.4 ). In an effort to combat this issue, scientific consortiums such as the Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network (CISNET) were formed so that scientific groups could work together, though they each used different inputs and statistical methods. These groups share the same goal of modeling the impact of breast cancer screening on mortality reduction.

With the vast number of scientific publications on mammography, the interpretations of the extent of the benefits vary. For some women, participating in breast cancer screening is important as it allows them to be engaged in an effort that is important to their health and, when they have normal screening exams, to be reassured until the next screening exam. While the absolute mortality benefit of screening mammography is less than we had hoped for, if you are the woman whose life was “saved” that benefit is important.

The Accumulation of Scientific Evidence on Potential Harms

While initial publications on breast cancer screening were aimed at determining whether breast cancer screening is beneficial and might save lives, over time, the possible harms of screening have become an increasingly important consideration. The potential risks are particularly relevant because breast cancer screening imposes a medical screening test on otherwise healthy women with the goal of saving lives through the early diagnosis of cancer.

Most RCTs only evaluated women undergoing a few rounds of screening. Yet, as breast cancer screening programs are implemented into clinical practice, women are increasingly screened annually over many decades. With this longer perspective, the accumulation of potential harms has become an increasingly important consideration. Questions were raised about the safety of imaging, given the repeated radiation exposure. Scientifically, there is no easy way to answer this question, but the amount of radiation per exam was lowered over time in response to these concerns.

After the early introduction of screening mammography into clinical practice, scientists began questioning the methods for studying cancer screening. Prominent among these individuals was Dr Bailar, a statistician from the US NCI of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), who described such concerning topics as lead time and length biases in an Annals of Internal Medicine article in 1976.

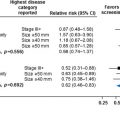

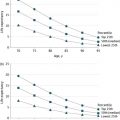

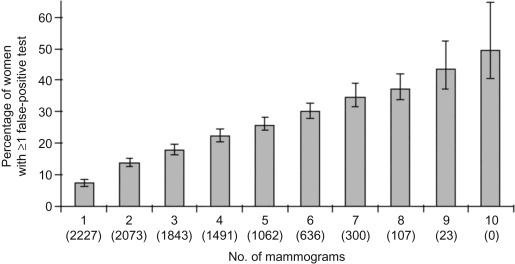

Women also began reporting extreme anxiety as a result of being called back for additional testing after their screening mammogram. Many women did not like receiving letters or telephone calls stating, “An abnormality has been noted on your screening mammogram and additional testing is recommended.” The majority of women called back for additional testing after screening mammograms have false-positive exams. One early study of women in the United States noted that after a decade of annual screening (1983–1993), about half of the women had experienced at least one false-positive mammography exam and about 20% had experienced a false-positive breast biopsy ( Fig. 1.5 ).

As breast cancer screening programs diffused into clinical practice, variable measures of sensitivity and specificity were also noted to be influenced by characteristics of the patients and the experience of the radiologists. Indeed, variability was even noted in the same radiologist who interpreted cases on two separate occasions.

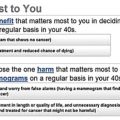

Interestingly, the false-positive rate after screening mammography varies between countries. Most women recalled for additional testing after a screening mammogram will not have cancer (and are thus a false-positive), as illustrated by the recall rate noted in publications from North America compared with other countries ( Fig. 1.6 ). It is apparent that the recall rate in North America is generally much higher. There are many potential reasons for the higher rate, including differences in the underlying patient population, age of women being screened, the threshold used by radiologists for calling women back after a screening mammogram, financial incentives, and the fear of medical malpractice litigation if cancer is missed. Table 1.2 lists some of the potential reasons for these striking differences between countries.