Breast Cancer Reconstruction | 8 |

Rachel Bluebond-Langner, Erin M. Rada, and Sheri Slezak

INTRODUCTION

Goals of Reconstruction

Breast reconstruction is usually not a single operation but rather a process that is an integral part of holistic care of the breast cancer patient. While women are initially concerned with their cancer diagnosis, most will go on to live long, normal lives. Over these years, many women find that breast reconstruction improves their ability to participate in desired activities, recover from cancer diagnosis, and ultimately achieve “wholeness.” Nationally, approximately 50% of patients choose to undergo breast reconstruction (1). Regardless, all patients should be educated by a plastic surgeon about their reconstructive options at the time of their diagnosis and counseled appropriately. Studies find that information given before surgery by both the oncologic surgeon and a plastic surgeon about reconstruction can mitigate some of the imagined fears of recurrence, pain, and out of pocket costs (2). Patients’ education impacts their quality of life, not only before surgery, but also long after finishing treatment.

Types of Reconstruction

In general, there are three types of breast reconstruction: autologous (utilizing the patient’s own tissue), implant-based (ultimately utilizing a breast implant), and oncoplastic reduction (preserving and reshaping breast tissue remaining after a partial mastectomy). Decision making regarding reconstruction requires a discussion between the patient and surgeon to determine a patient’s candidacy for various options based upon her body habitus, breast cancer treatment plan, medical and surgical comorbidities, and patient preferences. This makes the ultimate type of reconstruction a highly individualized decision for each patient. Differences between the implant and the autologous tissue breast reconstruction are shown in Table 8.1.

No Reconstruction/External Prosthesis

Approximately half of patients who undergo mastectomy choose no reconstruction (1). Many of these patients make this decision because they wanted to avoid further surgery; however, access to a plastic surgeon and preoperative counseling may also affect this decision. Patients who choose not to undergo reconstructive surgery may choose to wear an external prosthesis in their bra or other padded undergarments. There are, however, drawbacks to prostheses. Some women find them hot, heavy, and they may be displaced with movement or sports activities.

Table 8.1 Differences Between Expander/Implant and Autologous Tissue Reconstruction | ||

Type of reconstruction | Expander/implant | Autologous tissue reconstruction |

Surgery | 2 or 3 operations | Usually 2 operations |

General anesthesia | Yes | Yes |

Hospitalization | First stage: 1–2 days Second stage: outpatient | Usually 3–5 days |

Recovery period | 2–3 weeks | 4–8 weeks |

Need for multiple office visits | Yes (for expansion) | Yes |

Scars | Mastectomy scar only | Mastectomy scar and donor site scar |

Shape and consistency | No natural sag, may be firm | More natural shape, soft |

Potential problems | Breast hardening with shape change, skin ripples, infection, rupture | Abdominal weakness or bulge (TRAM), partial breast hardening, total flap loss |

Skin sensation | Altered in surgical areas | Altered in surgical areas |

TRAM, transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous. | ||

IMPLANT-BASED RECONSTRUCTION

Implant-based reconstruction refers to reconstruction ultimately utilizing a breast implant. At the time of mastectomy, either a permanent implant may be placed (sometimes referred to as “direct to implant”) or, more commonly, a tissue expander is placed. The tissue expander acts as a temporary placeholder and is serially expanded with saline over several weeks to months in the outpatient setting. It is ultimately replaced with a permanent implant in a second-stage outpatient operation.

Choosing Implant-Based Reconstruction

According to statistics reported by the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS), 106,338 women underwent breast reconstruction in 2015 (www.plasticsurgery.org/news/plastic-surgery-statistics). Seventy-three percent of these women opted to have tissue expansion and subsequent placement of an implant. In a survey of female board certified plastic surgeons in the United States, 66% reported that they would personally choose implant-based reconstruction if they underwent mastectomy (3). Of the female plastic surgeons who primarily perform implant-based surgery, 87% would choose expander-based reconstruction for themselves. Of the female surgeons who perform autologous reconstruction for the majority of their patients, about half would choose expanders for their own surgery.

Implants and Devices Used for Reconstruction

TISSUE EXPANDERS

Tissue expanders consist of a silicone outer membrane and an internal cavity that expands with the injection of filler. They come in a wide variety of sizes, shapes, and designs. Some surgeons use a one-shape-fits-all approach (since this is a temporary device) whereas others utilize a base diameter measurement or a target volume. Other choices include round, profiled, or dual chamber. Tissue expander ports are either integrated or remote.

If the mastectomy flaps allow, it is preferable to fill the expander to about half of the mastectomy breast weight so that the patient is not flat postoperatively. The amount of fill in the operating room can be varied given the thickness of the flaps, the quality of the muscle coverage, and the size of the breast. If the mastectomy flaps are thin or of questionable blood supply, then the expander can be left empty to place less stress on the flaps. A 50% fill in the operating room is typically enough for the patient to see some shape but not enough to give the patient severe pain or to compromise the flaps and incision.

Postoperatively, tissue expanders are then filled in the office by the physician or by an appropriate physician extender. The valve is found with a magnet and 60 to 180 mL of fluid is placed per session based upon patient tolerance. If too much is placed at once, patients can have considerable pain from stretching of the muscle. Muscle relaxants may be useful in these cases. Fills are continued every week or two until the desired size is obtained, or until the breast is a bit larger than the contralateral side. Often, chemotherapy or radiation therapy may be needed in the postoperative period. Expansion can be continued during chemotherapy, but the shape of the breast should not be altered during radiation therapy because the dosimetric plan would be compromised. Depending on the radiation techniques utilized at a given institution, a tissue expander may be deflated so that superficial electron beam radiation can effectively target the internal mammary nodes. There is no time limit in which expansion must be completed; expanders have been left in place for extended periods without difficulty. Alternative methods of expansion with air or carbon dioxide activated by the patient are currently being explored.

When expansion is complete, secondary surgery is scheduled to remove the expander and perform the definitive reconstruction with a permanent implant, autologous tissue, or autologous tissue and an implant.

BREAST IMPLANTS

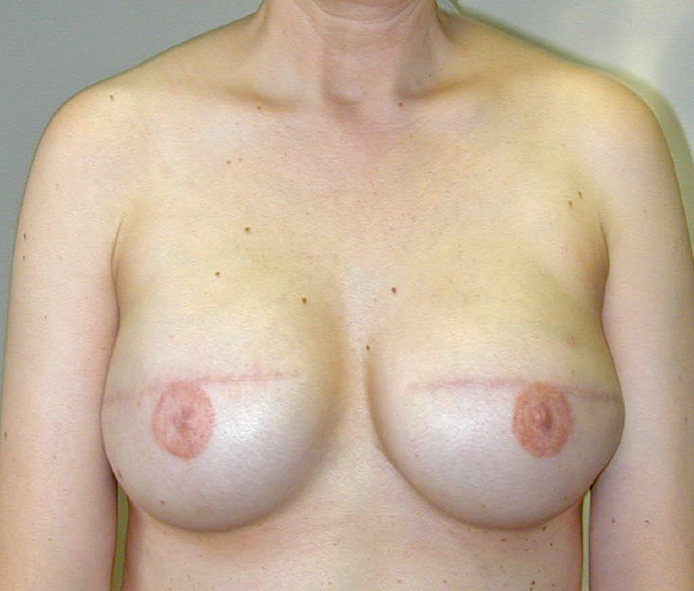

In the United States, breast implants are either saline- or silicone-filled. They are either profiled (form stable) or round, with a moderate to high projection, and have either textured or smooth surfaces. Current silicone implants are made with cohesive gel filler that has more crosslinking between silicone molecules than the silicone filler of previous generations. If cut in half, all currently available silicone implants remain intact like gelatin rather than leaking out. The vast majority of mastectomy (Figure 8.1) patients prefer silicone implants to saline because these implants are softer, feel more like normal tissue, move with the patient, and are more comfortable. Sizes range from 100 to 800 mL. Generally, the amount of saline placed in the expander is recorded and this is approximately the size of the implant chosen.

Figure 8.1 Bilateral mastectomy with implant reconstruction; nipples are tattooed.

Acellular Dermal Matrix Sling for Inferior Implant Coverage

The implant or the expander is most commonly placed below the pectoralis major muscle. Traditionally, it was covered by the pectoralis muscle, serratus, and rectus fascia. More commonly now, a prosthetic or bioprosthetic sling is used to bridge the gap between the lower edge of the pectoralis muscle and the inframammary fold. While acellular dermal matrix (ADM) is the most common sling material, there are alternatives including bovine, porcine, and poly vicryl substitutes.

The sling gives complete coverage of the implant, prevents displacement of the implant above the muscle or laterally into the axilla, pulls the pectoralis muscle down to prevent window shading up, defines the inframammary fold, and allows greater intraoperative fill volume. There is also data that ADMs decrease the incidence of capsular contracture. Ibrahim et al demonstrated improved breast contour and cosmetic appearance with an ADM sling, allowing the implant to sit lower with a more natural shape, better lower pole projection, and inframammary fold definition (4). Increased risk of complication with slings is still debated. Lee did a meta-analysis of 23 studies representing 6,199 cases (5). He found that the use of ADM significantly elevated the risks of infection, seroma, and mastectomy flap necrosis, but did not affect the risks of implant loss, unplanned reoperation, and total complications. Critics of acellular matrixes also cite its significant cost.

Advantages of Implant-Based-Reconstruction

1. There are no additional scars. Implant-based reconstruction uses the mastectomy defect only, and does not have any donor site morbidity or scars elsewhere in the body.

2. There is a faster overall recovery period. The operation is only 30 to 60 minutes longer than the mastectomy and the postoperative length of stay is the same—typically one day.

Disadvantages of Implant-Based Reconstruction

1. If tissue expanders are utilized, the patient must go through a period of expansion in the outpatient setting over several weeks to months depending upon the desired size followed by a second operation to replace the tissue expanders with permanent breast implants.

2. Expanders are typically placed below the pectoralis major muscle, which may cause more postoperative pain with expansion compared to some alternatives.

3. Breast implants tend to sit higher on the chest and do not descend as naturally over time. In patients with unilateral mastectomy, this may cause significant asymmetry requiring contralateral procedures.

4. Patients must be counseled that implants are not meant to be lifelong devices. Given the young age of many breast cancer patients, most will require implant exchange at least once over the course of their lifetime. Implants last about 15 years, but the range is variable.

5. The largest implant currently available on the market is 800 mL though many implant companies plan to expand their lines to include larger sizes. For women with large breasts prior to mastectomy, 800 mL may not be adequate.

Complications of Implant-Based Surgery

INFECTION

Infection of an implant poses a serious threat to the success of expander/implant-based reconstruction. Incidence is 3.4% to 34.4% (6–8). Risk factors for infection include breast size larger than “C,” previous irradiation, and repeat tissue expander placements (9). Organisms are most commonly staphylococcus species but may also include gram-negative rods and anaerobes. Cultures taken from the drains may help when choosing a course of antibiotics for patients with implant/expander-related infections. Treatment was historically implant removal followed by several months delay prior to a repeat reconstruction attempt. More recently, studies have shown successful treatment of up to 64.4% of patients with less severe infections using a combination of operative treatment and/or antibiotics (10,11). Patients successfully treated were stable with a normal white count and localized infection.

CAPSULAR CONTRACTURE

Capsular contracture has been a challenging complication since breast implants were introduced in 1960. Scarring around the implant causes a firm, high-riding breast that may be uncomfortably tight. Grade of capsular contracture is measured clinically according to the Baker Scale (Table 8.2) (12).

Table 8.2 Baker Capsular Contracture Scale After Prosthetic Breast Reconstruction | |

IA | Absolutely natural, cannot tell breast was reconstructed |

IB | Soft, but the implant is detectable by physical examination or inspection because of mastectomy |

II | Mildly firm reconstructed breast with an implant that may be visible and detectable by physical examination |

III | Moderately firm reconstructed breast. The implant is readily detectable, but the result may still be acceptable |

IV | Severe capsular contracture with unacceptable aesthetic outcome and/or significant patient symptoms requiring surgical intervention |

The rate of capsular contracture has improved with newer model implants. In recent studies, grade III/IV contracture ranges from 8.3% to 16.3% (6,8). Rates of contracture are higher in irradiated breasts.

The cause of capsular contracture is not well understood but various theories have been postulated including silicone bleed, subclinical infection, bacterial biofilm formation, foreign body reaction, allergy, and patient factors. In Del Pozo’s study of explanted breast prostheses, those with capsular contracture had a positive culture rate of 33% whereas those removed for other reasons had a 5% positive culture rate (13). Schreml et al found a 66.7% colonization rate for Baker III and IV capsules whereas no colonization was detected for Baker I and II capsules (14). Physicians have tried various strategies to avoid this complication including submuscular implant placement, textured implant shells, saline instead of silicone filler, ADM coverage, leukotriene antagonist administration, vitamin E therapy, ultrasound therapy, massage, and capsulectomy, all with various degrees of success.

MASTECTOMY FLAP ISCHEMIA

Flap ischemia can lead to necrosis, dehiscence, and loss of an expander. Implant-based surgery will only succeed if there is an adequate skin envelope to surround it. Extremely thin flaps are prone to necrosis and unlikely to succeed. Patients have different levels of adipose tissue, and some flaps are thinner in areas of the tumor. Methods of intraoperative perfusion assessment are becoming increasingly popular to assess perfusion to the mastectomy flaps. Newer technology provides an accurate and real-time intraoperative assessment of skin flap viability. If flow is inadequate, the plastic surgeon can excise the questionable area, place less fluid in the expander, delay the reconstruction, or plan to bring in new tissue with the use of autologous flaps.

FLUID COLLECTION

Hematoma and seroma are both complications that can occur after a large dead space is created during mastectomy. Rates of hematoma are lower than seroma, 1.3% and 4.9%, respectively (6,8).

Prevention of seromas is attempted with the use of closed suction drains at the time of mastectomy and expander placement. They are typically removed when drainage is less than 30 mL daily for three consecutive days. Persistent and high drainage may be a sign of a subclinical infection or a lymphatic leak. Other ways to prevent seromas that are less commonly performed include progressive tension sutures between the inferior pectoralis muscle or ADM and the skin flap, the use of new expanders with integral drain ports, and use of tissue glues.

While seromas may be aspirated, there is no conclusive data to guide the decision to aspirate secondary seromas or to let them resolve passively. The increased pressure of the seroma can make the process self-limiting, but this fluid is also a good medium for infection.

IMPLANT RUPTURE

Implant rupture may eventually occur in all patients. There is no evidence that a ruptured implant causes any health issues. It may present as a deflation (saline) or a change in firmness or contour (silicone). Many silicone ruptures are silent, so silicone implant ruptures must be evaluated with MRI. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommends that any ruptured implant be replaced or removed because it is not in the state that the manufacturer tested it.

The expander can deflate from a mechanical fault at a seam, or it can be accidentally injured at the time of surgery or during injections in the office. If close to the goal volume, one may simply proceed to implant exchange. If not, the expander must be replaced. Some expanders have flipped and the valve becomes inaccessible. Fixation of the tabs can make this less likely.

VISIBLE RIPPLING OR WRINKLING OF THE IMPLANT

Implant rippling has been reported in 3% to 10% of patients in several studies (8). Many mastectomy flaps are very thin, making the folds in the implant visible. There are several strategies to correct this. Silicone implants show fewer ripples than saline implants. Form stable implants have the least visible rippling. The surgeon can attempt to disguise ripples by placing ADM beneath the mastectomy flap to increase the thickness or tighten the muscle and capsule. Fat injections into the flaps can also disguise ripples. A latissimus dorsi flap can be rotated under the skin to provide more coverage. It is generally only ripples in the cleavage area that are bothersome to the patient.

Surveillance

Expanders and implants are typically placed below the pectoralis major muscle, deep to the breast, so cancer surveillance is performed via palpation. No further mammograms are needed. FDA recommendations for implant surveillance (in all cosmetic and reconstructive surgery patients) are baseline MRI 3 years postoperatively followed by every 2 years thereafter. With rupture rates under 8% at 10 years, some feel that this is overly aggressive and expensive. High-resolution ultrasounds may also provide adequate surveillance.

Direct-to-Implant Reconstruction

When women have small to moderate sized breasts with minimal to moderate ptosis and wish to remain the same size or smaller after reconstruction, it is possible to avoid the expansion process and go immediately to permanent implants. The maximum size of the implant that can be placed at the time of mastectomy depends on the mastectomy flap thickness, the available muscle, the patient’s desired size, and the use of local dermal flaps or ADM. A meta-analysis of 13 studies comparing direct-to-implant breast reconstructions with standard two-stage reconstructions revealed that wound infection, seroma, and capsular contracture risk were similar (15). Direct-to-implant reconstruction, however, had a higher risk for skin flap necrosis (OR, 1.43) and reoperation (OR, 1.25). It is imperative to choose the appropriate candidate for this procedure, but it is attractive in that it offers a one operation mastectomy and reconstruction. Tissue expanders should also be on hand in the operating room in case the flaps are thin or the perfusion to the flaps is questionable.

AUTOLOGOUS RECONSTRUCTION

Autologous reconstruction refers to procedures that utilize the patient’s own tissue to recreate the absent breast. Historically, autologous reconstruction referred to only pedicled flaps including transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous (TRAM) flaps and latissimus dorsi flaps. With advances in microsurgical techniques, free tissue transfer has become a mainstay of breast reconstruction.

Choosing Autologous Reconstruction

As with implant-based reconstruction, women choose to undergo autologous reconstruction for various reasons. While there is an additional donor site with a separate incision, many women like removal of excess skin and fat (ie, abdomen). While implants are safe, some women still develop unknown systemic complications from silicone. Other women do not like the idea of a foreign body and want their own tissue.

Donor Sites

The selection of donor site is based on the patient’s body habitus as well as desire. The abdomen and back are the two most common donor sites for autologous tissue. A flap from the abdomen can be harvested with skin, fat, and muscle (TRAM flap) or with only skin and fat, sparing the muscle (deep inferior epigastric perforator [DIEP] or superficial inferior epigastric artery [SIEA] flaps). The latissimus dorsi muscle (Figure 8.2) can be harvested with skin and fat that sits in the bra line and rotated around to the chest. Generally, an implant is needed behind the flap for adequate size and projection. The buttock tissue (superior or inferior gluteal artery perforator [SGAP/IGAP] flap) and inner thigh tissue (transverse upper gracilis [TUG] flap) are less common donor sites and usually reserved for women who are very thin but want their own tissue and do not want to use their back or in whom autologous tissue is needed but other donor sites are not available.

Advantages

1. Some patients need a large skin paddle to replace resected skin.

2. In unilateral breast reconstruction cases it is often easier to match a large and ptotic breast with the patient’s own fat.

3. Autologous tissue will produce more natural ptosis over time.

Figure 8.2 Left mastectomy with radiation; left latissimus dorsi and implant reconstruction; right mastopexy and augmentation.

4. One can avoid some of the prosthesis-related complications such as implant rupture, capsular contracture, and infection. If autologous tissue becomes infected it can be treated with antibiotics and occasionally wash out but the whole reconstruction is usually not lost.

5. While there is a donor site scar, many women like the idea of skin and fat being removed from another area of the body, particularly the abdomen.

6. Autologous tissue does not need to be replaced in 10 to 20 years.

Disadvantages

1. Longer operative time: Autologous tissue reconstruction has a longer operative time compared to implant reconstruction. Of the donor sites, the latissimus dorsi is the shortest, but a bilateral microsurgical reconstruction can be 10 to 12 hours or more. Longer operative times increase the risk of perioperative complications overall. Some patients, due to their comorbidities, may not be good candidates for microvascular reconstructions.

2. Flap failure: Microsurgical free tissue transfer has a failure rate of 1% to 10%. If the flap fails, an alternate form of reconstruction will need to be selected. Depending on the patient’s needs, this may be immediate placement of an implant, a latissimus dorsi with implant, or another free flap. This may require a second operation once the patient has healed. This can be very disappointing for both the patient and the surgeon.

3. Donor site morbidity: With all autologous reconstruction there will be some donor site morbidity although it may be minimal. The potential for donor site complications such as wound infection, abdominal weakness, bulge, or hernia (TRAM or DIEP) needs to be discussed with the patient preoperatively. While some people will counsel patients that a TRAM or a DIEP is just like a tummy tuck, the incision may be higher than in a cosmetic abdominoplasty and the abdominal musculature may be weakened, leading to a bulge or hernia in up to 10% of cases (16).

4. Longer recovery: While implant reconstruction is an outpatient procedure, autologous tissue reconstruction requires a one-night (latissimus dorsi) or three- to five-night (DIEP, TRAM, and SGAP) inpatient stay. The postoperative recovery is 3 weeks (latissimus dorsi) to 6 weeks (TRAM, DIEP, and SGAP).

AUTOLOGOUS/IMPLANT COMBINED RECONSTRUCTION

In addition to the implant-based and autologous breast reconstruction modalities described here, some patients will require both. This combination reconstruction is used when autologous tissue is required to provide adequate healthy soft tissue but the volume and projection of the breast with the flap alone are inadequate. The most common scenario is the use of a latissimus dorsi rotational flap with an implant.

Difference Between TRAM and DIEP

A TRAM flap takes some or all of the rectus abdominis muscle. Patients may have hernias, bulges, or weakness in sports or heavy lifting activities. A DIEP flap (Figure 8.3) spares the muscle although it is divided to get to the vessels. More muscle function is preserved.

ONCOPLASTIC BREAST RECONSTRUCTION TECHNIQUES

One of the greatest advances of the past 10 years has been the incorporation of plastic surgery techniques in breast conservation with excellent cosmesis. Although most lumpectomy patients need only primary closure, there are some difficult resections that will leave large deficits and gross asymmetry or leave defects in cosmetically sensitive locations, such as the areola or upper inner quadrant. Breast conserving therapy can be offered to more people with superior cosmetic results when oncoplastic reconstruction is considered.

In oncoplasty, there are two basic different approaches:

1. Volume-removal procedures, which combine resection with breast reduction and reshaping techniques, and

2. Volume-replacement techniques, using fat grafting, local flaps (glandular, fasciocutaneous, or latissimus dorsi), or implants to fill in the lumpectomy cavity.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree