Atypical Carcinoid Tumor

Mary Beth Beasley

Atypical carcinoid tumor (AC) is a rare pulmonary neoplasm. Carcinoid tumors as a whole make up 1% to 2% of all pulmonary malignancies and AC is estimated to represent 11% to 24% of this number.1 AC is defined in the 2004 World Health Organization (WHO) classification of pulmonary neoplasms as a carcinoid tumor with 2 to 10 mitoses per 10 HPF or necrosis. Most tumors will have both features, but it should be noted that occasionally a carcinoid will have necrosis without an elevated mitotic count and those tumors should be properly classified as AC. The current criteria were proposed in 1998 by Travis et al.2,3 and were subsequently incorporated into the 1999 WHO classification. The evolution and continued debate regarding the appropriate criteria and nomenclature of these tumors are discussed in Chapter 12; however, one should note that, given the evolution of criteria for the classification of AC, older literature should be interpreted with caution given that some tumors previously classified as AC may be better classified as other neuroendocrine tumors given current guidelines.

The clinical characteristics of AC are similar to those of typical carcinoid tumors (TCs; see Chapter 10), although AC occurs in a slightly older age group and approximately 60% of patients with AC have a history of cigarette smoking. AC has a worse prognosis in comparison to TC, with a 5-year survival rate of 60% to 70% and a 10-year survival of 35% to 50%.1,2,4,5 Lymph node metastases are present at the time of diagnosis in approximately 30% to 40% of patients.1,2,4,6 The presence of nodal disease significantly effects prognosis in most studies, with one study reporting a 5-year survival of only 22% in patients with N2 disease.1 Like TC, some cases of AC have been reported to arise in a background of diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia.7

ATYPICAL CARCINOID TUMORS, CYTOLOGY

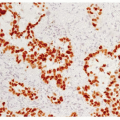

Cytologically, ACs show features similar to those of TCs, including round, uniform nuclei and abundant cytoplasm, with additional cytologic features including necrosis and mitotic figures.

ATYPICAL CARCINOID TUMORS, GROSS FEATURES

ACs have the same gross appearance as TCs, typically measuring between 2 and 4 cm in diameter. The tumor may protrude into the airway, and occasionally may obstruct the airway lumen. ACs are usually tan to yellow-red on cut section; and in some cases, foci of hemorrhage, not characteristic of TCs, may be evident. Also, more ACs arise peripherally than do TCs (Fig. 11-1).

ATYPICAL CARCINOID TUMORS, HISTOLOGY

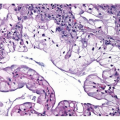

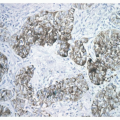

Like TC, AC is typically composed of a relatively uniform population of round to polygonal cells with finely granular chromatin and moderately abundant cytoplasm. AC most commonly has an organoid pattern of growth (Fig. 11-2), but an array of patterns similar to that in TC may also

be encountered as well as areas of solid, less well-organized growth.4 Nuclear pleomorphism is a point of interest. Pleomorphism is more commonly encountered in AC, but in the 1998 study by Travis et al.,2,3 pleomorphism did not correlate with a worse prognosis by multivariate analysis and, therefore, is not currently included in the WHO definition as a factor discriminating TC from AC. As stated above, AC is distinguished from TC by the presence of necrosis or a mitotic count of 2 to 10 per 10 HPF. The necrosis is typically located within the center of the organoid tumor nests and may be focal or punctuate ( Figs. 11-3,11-4,11-5,11-6,11-7,11-8 and 11-9). Occasional cases may have larger areas of infarct-like necrosis.3,4 As these discriminating features may be present only focally, absence of these features on a core or transbronchial biopsy does not exclude an atypical carcinoid. As such, small biopsies should be designated “carcinoid tumor” with final classification left to a resected specimen. Tumors with a mitotic rate of 6 to 10 mitoses per 10 HPF have been shown to have a worse prognosis than those with 2 to 5 mitoses per 10 HPF.4 Like TC, AC is treated surgically and typically shows minimal response to chemotherapy. Studies evaluating AC in regard to potential targeted therapies are discussed in Chapter 10.

be encountered as well as areas of solid, less well-organized growth.4 Nuclear pleomorphism is a point of interest. Pleomorphism is more commonly encountered in AC, but in the 1998 study by Travis et al.,2,3 pleomorphism did not correlate with a worse prognosis by multivariate analysis and, therefore, is not currently included in the WHO definition as a factor discriminating TC from AC. As stated above, AC is distinguished from TC by the presence of necrosis or a mitotic count of 2 to 10 per 10 HPF. The necrosis is typically located within the center of the organoid tumor nests and may be focal or punctuate ( Figs. 11-3,11-4,11-5,11-6,11-7,11-8 and 11-9). Occasional cases may have larger areas of infarct-like necrosis.3,4 As these discriminating features may be present only focally, absence of these features on a core or transbronchial biopsy does not exclude an atypical carcinoid. As such, small biopsies should be designated “carcinoid tumor” with final classification left to a resected specimen. Tumors with a mitotic rate of 6 to 10 mitoses per 10 HPF have been shown to have a worse prognosis than those with 2 to 5 mitoses per 10 HPF.4 Like TC, AC is treated surgically and typically shows minimal response to chemotherapy. Studies evaluating AC in regard to potential targeted therapies are discussed in Chapter 10.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree