3.1 Introduction

Diet is one of the most important and modifiable lifestyle determinants of human health. Both undernutrition and overnutrition play a major role in morbidity and mortality, and therefore assessment of nutritional status is a cornerstone of efforts to improve the health of individuals and populations throughout the world. There are four main approaches to assessing nutritional status:

- anthropometry, which measures the dimensions and composition of the human body

- biomarkers, which reflect either nutrient intake or the impact of nutrient intake

- clinical assessment, which ascertains the clinical consequences of imbalanced nutrient intakes

- dietary assessment, which estimates food and/or nutrient intakes.

Each of these approaches has different strengths and limitations specific to their use in individuals versus populations. In addition, each varies markedly in terms of feasibility and costs associated with the data collection. Given the context of public health nutrition, this chapter will focus on anthropometry, biomarkers and dietary assessment, and largely excludes clinical assessment.

Table 3.1 Overview of issues related to assessing nutritional status in individuals and populations

| Nutrition assessment purpose | Assessment data needed for | |

| Individual | Population | |

| Clinical | Determination of an individual’s nutritional status for purposes of treatment or counseling | Characterization of nutritional status of a patient population by estimation of mean measures of nutritional status for the group |

| Characterization of nutritional status of a patient population by determination of proportion of individuals meeting (or not meeting) some standard of nutritional status | ||

| Public health | Nutrition monitoring and surveillance by determination of proportion of individuals in the population meeting (or not meeting) a standard of nutritional status | Nutrition monitoring and surveillance by estimation of mean measures of nutritional status for the group |

| Research | Research relating an individual’s nutritional status to his or her nutrition-related outcome (e.g. disease status) | Comparison of mean measures of nutritional status by groups |

When selecting a nutrition assessment method, an important consideration is the context in which the data will be used. The uses of assessment data can be broadly grouped as follows:

- clinical settings for determination of a person’s dietary adequacy or risk and for purposes of treatment or counseling; assessment data are sometimes used clinically to characterize patient populations

- public health settings for nutrition monitoring and surveillance of populations for dietary adequacy or risk, public policy decisions related to food assistance programs, fortification, safety and labeling, and development of public health recommendations for dietary intake

- research settings for epidemiological studies on dietary intake and disease risk and for comparison of groups, such as intervention versus control groups in a randomized controlled trial.

- Dietary self-report measures are the only type of nutritional status assessments that can provide detailed data on food choices, which is ultimately the behavior that must be modified to improve health and reduce risk of disease. However, these methods tend to be costly and burdensome and are prone to significant error and bias.

- Biomarker measures are objective and can be accurate. However, many biomarkers only weakly reflect dietary intake or nutritional status because of metabolic control and other nondietary factors affecting their levels. In addition, collection and analysis of biological samples are often difficult and costly.

- Anthropometric (i.e. height and weight) measures are easy to collect and accurate. However, these measures are a function of physical activity as well as diet and only reflect long-term energy balance.

Table 3.2 provides a summary of recommendations for appropriate use of nutritional assessment measures in individuals and populations. It is clear that choosing the appropriate nutritional status measure is a complex decision based on the objective of the data collection and the target group (individual or population), with an eye towards the competing demands of accuracy and practicality. There is no right or wrong approach, but only the best measure given the objective of the assessment and the availability of resources.

3.2 Dietary assessment

Assessment of dietary intake offers considerable challenge. Over the course of a week, an individual can consume hundreds of foods, making it difficult for respondents to report their intake accurately. Meals may be prepared by others, so that respondents may not know exactly what, or how much, they ate. Food choices typically vary with seasons and other life activities (e.g. weekends and vacations). In addition, foods themselves are often a surrogate for the variable of interest (e.g. dietary fat), which means that investigators must rely on the accuracy and completeness of food composition databases.

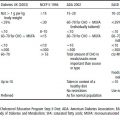

Table 3.2 Recommendations for appropriate uses of major nutritional assessment measures

| Assessment measure | Appropriate | Not recommended |

| A single, 24 h measure of dietary intake (record or recall) | For characterization of current, mean intakes of groups For international comparisons of nutrient intakes | In retrospective studies When characterization of usual diet is desired In cases where the exposure of interest (i.e. food) is rarely consumed |

| Replicate measures of food intake on specified days (records or recalls) | For characterization of current, usual diet in groups or individuals | In retrospective studies For studies where respondent burden must be minimized |

| Food frequency questionnaire | For studies of diet and health where the biologically relevant exposure is usual long-term diet In retrospective studies | If study sample size is small For surveillance and monitoring where accurate absolute intakes are required For use in a population other than that for which the questionnaire was developed, unless dietary habits are very similar in the two populations In clinical situations where precise intake estimates are needed If information on dietary patterns (e.g. meals per day or meals consumed away from home) is needed |

| Brief dietary assessment measures | In studies where respondent burden or cost issues prohibit comprehensive dietary assessment | Where it may become desirable to characterize entire diet When precise estimates of intake are required |

| Biomarkers | When an objective measure of nutritional status is needed Where an appropriate biomarker is available | Where there is lack of standardized methodology For individuals if assays are imprecise For individuals when there are no criteria for determining dietary adequacy or risk |

| Anthropometric assessments | For identification of long-term energy deprivation or excess | If recent changes in nutritional status are of interest For identification of specific nutrient deficiencies |

An additional complication with regard to studies of diet and health is that since the early 1980s research has concentrated on the identification of foods and constituents of foods (e.g. nutrients and other bioactive compounds) that cause, or protect against, the occurrence of chronic diseases. These diseases develop over many years and therefore the exposure of interest is usual dietary intake throughout the past 10–20 years. This time lag between dietary exposure and disease occurrence presents significant difficulties in the study of diet and chronic disease.

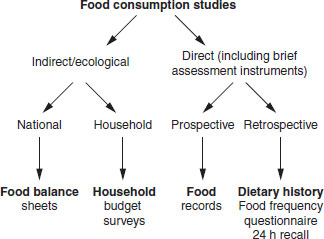

Figure 3.1 gives an overview of the options available for the measurement of food intake. The primary focus in this chapter is on the direct measurement of food intake and thus only a brief overview of indirect methods is provided.

Food balance sheets

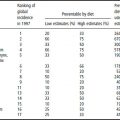

Food balance sheets represent the “disappearance” of food, which can be a surrogate for consumption. The values are based on the difference between production of food A plus its imports, minus the export of food A plus its use in animal feed. This net value is divided by the population to calculate a disappearance value, which is measured in kilograms per capita per year. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations prepares annual food balance sheets that give, on a country-to-country basis, an indication of how the disappearance of foods has changed over time. When these foods are converted to nutrients these data can help to monitor how nutrient intakes compare with some reference value or how the intakes change with time. While these data are not usable for individual assessments, they have been of great benefit in international PHN. In addition, these population intakes have been correlated with disease incidence across countries in provocative hypothesis-generating studies, many of which show a strong correlation between per capita fat intake and cancer incidence. However, the use of these data requires a clear understanding of their strengths and weaknesses.

Figure 3.1 Overview of methods available for the measurement of food intake.

- Strengths: food balance sheets are an inexpensive way of routinely monitoring global food and/or nutrient intakes using a standardized methodology.

- Weaknesses: cross-country comparisons of food balance sheet data should be done cautiously and with an understanding of the limitations of such comparisons. First, there are problems with the denominator (i.e. the population) used in calculating these figures. Specifically, there are marked differences in the accuracy with which populations are measured. In addition, the demographic composition of populations varies widely, with a higher proportion of infants and children in less developed countries than in more developed countries. Secondly, in developed countries, there is a remarkably high level of wastage of food at domestic and catering level, which is not measured. Therefore, in developed countries, the food balance sheet estimates of energy intake exceed estimates of energy intakes using direct methods. Finally, the nutritional composition of foods may vary greatly across countries. Fat levels of meat may vary, as will be types of meat consumed (e.g. muscle versus offal) and therefore the true nutrient compositions of a food may vary geographically.

Notwithstanding these shortcomings, such data are invaluable to those charged with the difficult task of monitoring global nutrition patterns.

Household budget surveys

Most economies conduct regular measures of household expenditure on a variety of items, including food, to calculate economic indices. If food prices are known, then household expenditure on food can be translated into household food purchase. If the composition of the household is known, then food purchase can be translated into weights of foods or nutrients per household member, which is the basis of household budget surveys. As with food balance sheets, these data have their strengths and weaknesses.

- Strengths: household budget survey data are relatively inexpensive to restructure for food consumption data and provide a time-trend in national food supplies.

- Weaknesses: one of the major limitations to these data is that in many countries, data on food purchased for consumption outside the home are not recorded. This omission can significantly distort nutrient intake given that in many developed countries as much as 30% of energy may be obtained outside the home. Household budget survey data suffer some of the same limitations of food balance sheets in that neither method records food loss during preparation or plate waste. As with food balance sheets, the denominator can be difficult to interpret in that although the food entering the home can be quantified, it is not possible to determine which members of the household consumed which foods and what proportions of them.

In summary, both food balance sheets and household budget surveys are part of a repertoire of options for measuring food intakes that national and public health nutritionists can use. They are inexpensive and widely available and therefore of great importance in countries where there is no infrastructure for the collection of dietary data.

The ensuing sections outline several dietary assessment methods:

- food records and recalls, which measure intake on specified days

- diet history and food frequency questionnaires, which measure usual intake

- brief dietary assessment instruments.

An overview of methods for assessing vitamin and mineral supplement use is also provided. Additional details on dietary assessment can be found in Introduction to Human Nutrition: Chapter 10: Measuring Food Intake.

Measurement of dietary intake on specified days: food records and recalls

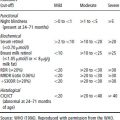

Table 3.3 provides an overview of issues related to use of food records and recalls for assessing nutritional status in individuals and populations.

Food records

For many years, food records were considered the gold standard of dietary assessment. In brief, food records require individuals to record everything consumed over a specified period, usually 1–7 days. Respondents are typically asked to carry the record with them and to record foods as eaten. Some protocols require participants to weigh and/or measure foods before eating, while less stringent protocols use models and other aids to instruct respondents on estimating serving sizes. To ensure that sufficient detail is captured on foods and preparation methods, instruction on keeping records should be provided before the recording period and the record should be reviewed for completeness after the recording period. In theory, a food record provides a perfect snapshot of food consumed. In practice, there are considerable problems with this method for assessing food intake, including the large respondent burden of recording food intake and the impact on usual food consumption caused by record keeping. Respondents may alter their normal food choices merely to simplify record keeping or because they are sensitized to food choices. The latter reason may be more likely among women, restrained eaters, obese respondents or participants in a dietary intervention. Other sources of error by respondents include mistakes or omissions in describing foods and assessing portion sizes.

Dietary recalls

Dietary recalls are an interview in which the respondent is asked to describe all the foods and beverages consumed in the previous 24 h. Unannounced recalls are often recommended because respondents cannot change what they ate retrospectively and therefore this instrument cannot alter respondent eating patterns. The major disadvantage to dietary recalls is that they rely on the respondent’s memory and ability to estimate portion sizes. In addition, it cannot be verified that social desirability does not influence self-report of the previous day’s intake. A noteworthy advantage of 24 h recalls is that they are appropriate in low-literacy populations for whom recording food intake is not practical. Finally, because recalls are interviewer administered, the data can be collected in a highly consistent manner from all respondents.

Table 3.3 Overview of issues related to use of food records and recalls for assessing nutritional status in individuals and populations

| Nutrition assessment purpose | Assessment data needed for | |

| Individual | Population | |

| Clinical | Qualitative assessment of a “usual” day’s intake has a long clinical history as useful method for identifying dietary problem areas and tailoring counseling | Not typically used in patient populations because of burden to respondents, many of whom may be ill or have little control of dietary intake (e.g. hospitalized patients) |

| Public health | Because multiple days of intake are required to assess usual intake in an individual, these methods are less useful when the goal is to determine the proportion of individuals below some standard, such as the percentage of population consuming <30% energy from fat | A single food record or 24h dietary recall is useful for characterizing mean intakes in a population because of the open-ended nature of assessment and relatively low burden and costs |

| Research | Used most frequently in small research studies where respondents are selected for willingness to record multiple days of intake or complete multiple recalls | Useful where the goal is to assess mean intakes by groups, such as dietary interventions comparing control versus intervention groups Recalls considered desirable for interventions as they are believed to be less prone to bias associated with the dietary intervention itself |

Use of food records and recalls for assessing nutritional status in individuals and populations

Records and recalls have proven very useful in studies of populations, particularly for purposes of nutrition monitoring. A single day’s intake can provide reliable estimates of the mean intake of large groups. Because these methods are open-ended, they are appropriate for assessing intake among population groups with markedly different eating patterns. Records and recalls are often used for evaluating dietary interventions where the goal is to compare mean intakes in the intervention versus the control group.

An important limitation to these methods is that a single day’s intake cannot be used to study distributions of dietary intake because on any one day, an individual’s diet can be unusually high (e.g. a celebratory meal) or unusually low (e.g. a sick day). These days are not representative of an individual’s usual intake even though they may be perfectly recorded. This day-to-day variation in intake is a type of random variation that does not bias the estimation of mean intake for a group. However, this variability does result in an increased distribution of observed intake (i.e. a wide standard deviation), as shown in Figure 3.2. These issues need to be considered whenever data from a single day’s intake are presented. For example, when looking at the distribution of energy intake in Figure 3.2(a), it is important to remember that the unit of observation is days, not individuals. Therefore, it is correct to conclude that on 2.3% of days, individuals consumed less than 1000 kcal. However, it is incorrect to conclude that 2.3% of individuals usually consume less than 1000 kcal. As shown in Figure 3.2(b), when a mean of 6 days of intake is used to estimate dietary intake, there are no observations below 1000 kcal.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree