| Altered level of consciousness |

| General anesthesia Narcotic and sedative drugs Drug overdose and ethanol toxicity Metabolic encephalopathies (electrolyte imbalances, liver failure, uremia, sepsis) Hypoxia and hypercapnia Central nervous system (CNS) infections Dementia |

| Abnormal glottic closure |

| Anesthetic induction or postanesthetic recovery Postextubation Structural lesions of the CNS (tumors, cerebrovascular accident, head trauma) Seizures Infection (e.g., diphtheria, pharyngeal abscess) |

| Gastroesophageal dysfunction |

| Alkaline gastric pH Gastrointestinal tract dysmotility Esophagitis (infectious, postradiation) Hiatal hernia Scleroderma Esophageal motility disorders (achalasia, megaesophagus) Tracheoesophageal fistula Ascites (increased intra-abdominal pressure) Intestinal obstruction or ileus Diabetes (functional gastric outlet obstruction) |

| Neuromuscular diseases |

| Guillain–Barré syndrome Botulism Muscular dystrophy Parkinson’s disease Polymyositis Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis Multiple sclerosis Myasthenia gravis Poliomyelitis Tardive dyskinesia |

| Mechanical factors |

| Nasogastric or enteral feeding tubes Upper endoscopy Emergency and routine airway manipulation Surgery or trauma to the neck and pharynx Tumors of the upper airway Tracheostomy Endotracheal tube Zenker’s diverticulum |

| Other factors |

| Obesity Pregnancy |

Clinical epidemiology

In 2010 there were approximately 190 000 inpatient admissions in the United States for which the principal diagnosis was food/vomit (or aspiration) pneumonitis (ICD-9 507.0). These hospitalizations accounted for more than 19 000 inpatient deaths with a total medical care cost of 2.7 billion dollars. Another 370 000 persons received a secondary diagnosis of aspiration pneumonitis. Swallowing disorders due to neurologic diseases affect 300 000 to 600 000 people each year in the United States. Nearly 40% of stroke patients with dysphagia aspirate and develop pneumonia. Overall, aspiration pneumonitis accounts for approximately 0.5% of all hospitalizations, 3% to 4% of inpatient mortality, and 5% to 23% of all cases of community-acquired pneumonia.

More than 70% of cases of aspiration pneumonia are in persons older than 65 years of age. As a corollary, aspiration pneumonia is the second most frequent principal cause of hospitalizations among United States Medicare patients. Among nursing home patients, aspiration pneumonia accounts for up to 30% of cases of pneumonia, occurs at a rate three times that of age-matched patients in the community, and markedly increases the risk of death. Among such patients, difficulty swallowing food, use of tube feedings, requiring assistance with feeding, delirium, and use of sedative medications are the most frequent risk factors for aspiration pneumonia. While the debilitated elderly are at particularly high risk, prior silent aspiration is also common in apparently healthy elderly patients with community-acquired pneumonia.

Aspiration complicates the course of approximately 10% of persons admitted to hospitals for overdosage with sedative or hypnotic agents and 0.05% to 0.8% of persons receiving general anesthesia for surgical procedures. Patient characteristics independently associated with an increased risk of aspiration following general anesthesia include male sex, nonwhite race, age of >60 years, dementia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, renal disease, malignancy, moderate to severe liver disease, and emergency surgery.

Clinical course and diagnosis

Aspiration of gastric contents results in acute inflammation of the major airways and lung parenchyma with maximal hypoxemia within 10 minutes of aspiration. Local injury results in complement activation as well as release of tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-8, and other proinflammatory cytokines that in turn are primarily responsible for the acute nonobstructive complications of chemical aspiration. The severity of lung injury is greatest when the pH is less than 2.5, but severe pulmonary injury does occur at higher pH.

Acute symptoms and signs of chemical pneumonitis include respiratory distress, fever, cough, reflex bronchospasm, leukocytosis, and pulmonary infiltrates. Life-threatening hypoxemia may develop as a consequence of atelectasis, pulmonary capillary leak, and direct alveolar damage. These findings are easily attributable to chemical pneumonitis if they follow witnessed vomiting and aspiration of gastric acidic contents. If the event is not witnessed, detection of the gastric enzyme pepsin in a tracheal aspirate may serve as a marker for gastric aspiration pneumonitis.

Many patients with chemical pneumonitis improve without any specific antimicrobial therapy. Other patients develop progressive clinical symptoms and worsening radiographic findings for several days after an aspiration event. Such progression indicates the emergence of the acute respiratory distress syndrome and/or bacterial pneumonia. Alternatively, patients may initially improve for several days but then worsen with the onset of recurrent symptoms and signs indicative of secondary bacterial pneumonia.

Differentiation of aspiration pneumonia from progressive chemical pneumonitis is often challenging as there is frequent overlap between these two syndromes. This distinction is important given the desirability of avoiding unnecessary antibiotic use, especially as pneumonia fails to develop in approximately half of all aspiration events. Furthermore, given the differences in microbial etiology of aspiration pneumonia versus community-acquired pneumonia, it is important to consider aspiration in persons with pneumonia who have the risk factors listed in Table 34.1 even if an aspiration event has not been witnessed.

The clinical presentation of aspiration pneumonia is much less dramatic than that of chemical pneumonitis. Many episodes of aspiration pneumonia, especially those involving normal oral flora (i.e., mixed aerobic/anaerobic infections), result from silent aspiration. Clinical characteristics include fever, alteration of general well-being, and respiratory symptoms such as productive cough, dyspnea, and pleuritic pain. In elderly patients with aspiration pneumonia, the early signs and symptoms of pulmonary infection may be muted and overshadowed by nonspecific complaints such as general weakness, decreased appetite, altered mental status, or decompensation of underlying diseases. These patients may have an indolent disease and not develop fever, malaise, weight loss, and cough for 1 to 2 weeks or more after aspiration. This is an especially common presentation for patients who present with mixed aerobic/anaerobic lung abscesses or empyemas after an aspiration event.

Neither routine nor specialized laboratory tests, e.g., C-reactive protein, soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells (TREM-1), lipid-laden macrophage, and serum procalcitonin distinguish between aspiration pneumonitis and aspiration pneumonia. The role of procalcitonin and amylase in bronchoalveolar lavage remains to be established.

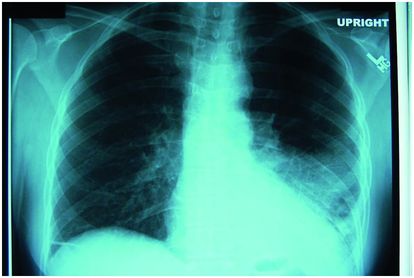

Radiographic evaluation is necessary to establish the diagnosis of pneumonia as there is no combination of historical data, physical findings, or laboratory results that reliably confirms the diagnosis. Limitations of chest radiography for the diagnosis of pneumonia include poor specificity in patients with the acute respiratory distress syndrome and decreased sensitivity in persons with previous structural lung disease, very early infection, severe dehydration, or profound granulocytopenia. Otherwise, the failure to detect an infiltrate essentially rules out the diagnosis of pneumonia. Although spiral computed tomography (CT) of the chest provides a more sensitive means of detecting infiltrates than chest radiography, such infiltrates may not actually represent pneumonia. Esophagography and CT are especially useful in the evaluation of aspiration disease related to tracheoesophageal or tracheopulmonary fistula.

Radiologic findings do not distinguish between chemical pneumonitis and aspiration pneumonia, save for the fact that radiologic abnormalities typically have a more rapid onset with chemical pneumonitis. However, when compared with other causes of pneumonia, pneumonia complicating aspiration more often involves the posterior segment of the right upper lobe, the superior segment of the right lower lobe, or both, as well as the corresponding segments in the left lung. Manifestations of severe, mixed aerobic/anaerobic infection include necrotizing pneumonia, lung abscess, and empyema (Figures 34.1–34.4). Foreign-body aspiration typically occurs in children and manifests as obstructive lobar or segmental overinflation or atelectasis. An extensive, patchy bronchopneumonic pattern may be observed in patients following massive aspiration of gastric contents.