The appendix is a rare site of malignancy, with a large variety of histologic subtypes. Reviews of large series of appendectomies reveal appendiceal neoplasms in nearly 0.7% to 0.9% of cases.1,2 Even with the large number of appendectomies performed annually in the United States, appendiceal malignancies remain a rare entity, comprising less than 1% of colorectal malignancies. The age-adjusted risk of development of appendiceal cancer is estimated at just 0.12 cases per 1,000,000 per year.3,4 The rarity of the diagnosis makes database reviews and small series the primary source of information regarding frequency of diagnoses and outcomes. McCusker was the first to conduct a review of the SEER database, reviewing 2117 appendiceal malignancies reported to SEER between 1973 and 1998.4 Additional SEER reviews based on the same population but extending the time interval slightly have been published by McGory and Turaga, revealing fairly similar results.5,6

While the SEER database provides no information regarding the clinical presentation of patients with appendiceal malignancies, large case series confirm that the diagnosis is seldom made prior to surgery. Patients with appendiceal neoplasms commonly present with signs and symptoms of appendicitis. The diagnosis is often not suspected intraoperatively, and a finding of cancer may not be made until the pathologic analysis. While the majority present with presumed appendicitis, a sizable minority of patients are diagnosed via imaging performed for abdominal pain or as incidental findings in the workup of other complaints.

Benign neoplasms represent between 20% and 40% of appendiceal malignancies, and include leiomyomas, neuromas, and lipomas.7 Lesions of intermediate behavior include low-grade mucinous neoplasms as well as typical carcinoid tumors. More aggressive malignant neoplasms include atypical carcinoid, adenocarcinoma, and goblet cell carcinoid. The 7th edition of the AJCC staging manual introduces separate staging systems for typical carcinoids and all other appendiceal tumors. However, the behavior and management of appendiceal neoplasms vary widely. Due to their differing features, prognosis, and treatment they will be discussed individually in this chapter, but a general classification scheme is shown in Table 105-1. Pseudomyxoma peritonei, the term used to describe peritoneal dissemination of a mucus-producing malignancy, may originate from appendiceal malignancies, and is included in the types of appendiceal cancer discussed in this chapter.

The term “karzinoid” was coined by the German pathologist Sigfried Oberndofer, and reflected his understanding that the behavior of carcinoid tumors was less aggressive than that of typical adenocarcinoma.8 While carcinoid tumors develop not only in the digestive tract but also within the lung, the appendix is disproportionately represented as a common site of disease. In a large series including 8305 carcinoid tumors from all sites, the appendix was the most common individual site of the primary tumor—19% of all carcinoid tumors in the series.9 In contrast to other appendiceal tumors, carcinoids demonstrate a female predominance on the order of 2–2.7 : 1.10,11 In addition, carcinoids tend to present at a younger age than other appendiceal malignancies. The average patient diagnosed with appendiceal carcinoid is in their early 40s.9,12

While some reviews suggest appendiceal carcinoids comprise as high as 57% of all appendiceal tumors,1 this is likely an overestimate due to inclusion of goblet cell carcinoids in addition to typical carcinoid tumors. (Goblet cell carcinoids, which have features of both neuroendocrine tumors as well as gland-forming elements, are also termed adenocarcinoid and are discussed in the subsequent section.) Recent estimates of the frequency of appendiceal carcinoid are in the range of 20% of all appendiceal malignancies.4 Subsequent SEER reviews report this number as being even lower.5,6 While the incidence of appendiceal carcinoids has not likely changed significantly, this may reflect better differentiation between classical carcinoid and other tumors. Furthermore, pathologists may classify some carcinoid tumors without nuclear atypia or mitotic figures as benign. Consequently, only tumors with evidence of nodal or distant spread, or malignant histology may be classified as “malignant” carcinoid. This differentiation may result in classic carcinoid being considered benign, and as such not reported to SEER databases.11

Histologic analysis of both normal appendices and typical appendiceal carcinoids suggest typical appendiceal carcinoid tumors likely arise from a different neuroendocrine cell than other carcinoid tumors. Instead of arising from epithelial neuroendocrine cells as in most other gastrointestinal carcinoids, appendiceal carcinoids appear to arise from subepithelial neuroendocrine cells.13,14 This is likely responsible for the lower age range for patients with appendiceal carcinoid (manifesting shortly after the population of subepithelial neuroendocrine cells reaches an age related peak in the appendix), as well as the typical location in the tip of the appendix, where subepithelial neuroendocrine cells are more numerous.13 In one large series of carcinoid tumors, two-thirds of tumors were located in the tip of the appendix, with another 20% in the body of the appendix.12

In spite of portending a favorable prognosis, appendiceal carcinoid tumors are reported to have a high incidence of lymph node metastases (LNM)—up to five times the rate of LNM associated with the so-called “mixed neuroendocrine appendiceal neoplasms.”15 However, these data are difficult to interpret as they come from the SEER administrative database and were not subjected to a consistent pathologic review process. In a separate analysis of SEER data that included only patients with “typical” carcinoid, the authors found that 44 of 89 patients (49%) had LNM.11 The calculated rate of lymph node involvement was 15% for tumors less than or equal to 1 cm in size, 47% for tumors between 1 and 2 cm, and 86% in patients with tumors larger than 2 cm.11 The authors excluded patients with incomplete pathology, which may have inadvertently enriched the cohort with node-positive patients. Although the rate of LNM was quite high in this series, 10-year survival remained greater than 90%. The high 10-year survival was even noted among patients with tumors more than 2 cm in size with nodal spread, calling into question the prognostic significance of positive lymph nodes.11

Many patients with metastatic carcinoid live for long periods prior to succumbing to their disease. For this reason, 10-year overall survival may not be the ideal outcome to follow. In an older series from a single institution, 122 patients with typical appendiceal carcinoid tumors less than 2 cm in size were reported as having undergone appendectomy alone. In median follow up of 14 years, no patients with tumors between 1 and 2 cm developed recurrence or metastatic disease, nor did any of the 100 patients with tumors less than or equal to 1 cm.12 This suggests that LNM in appendiceal carcinoid tumors smaller than 2 cm are either uncommon, or alternatively may not be clinically significant.

Because of the relatively indolent nature of carcinoid tumors of the appendix, the role of right hemicolectomy in the treatment of appendiceal carcinoid has been questioned. Traditionally, right hemicolectomy was advised for tumors larger than 2 cm in size, involvement of the base of the appendix, or mesoappendiceal invasion. The first two criteria remain accepted indications for right hemicolectomy in appendiceal carcinoid, however, the last criteria has been questioned in one recent review. Of 42 primary neuroendocrine tumors of the appendix evaluated at one institution, 15 had invasion of the mesoappendix; none of these patients developed local disease recurrence or metastasis over mean follow-up of 52.6 months.16 Currently, retrospective data support the use of appendectomy alone for tumors less than or equal to 1 cm in size. While the high incidence of lymph node involvement with larger tumors may not have a significant impact on outcome, there is a paucity of data regarding appendectomy alone with larger tumors. Consequently, right hemicolectomy is still generally endorsed for carcinoids greater than 2 cm in size. The optimal treatment for carcinoids between 1 and 2 cm remains unknown but appendectomy alone has been considered sufficient by many authors. This is supported by Moertel’s data indicating that none of the 22 patients with carcinoids between 1 and 2 cm in size developed recurrent or metastatic disease with median follow-up of 14 years.12

Appendiceal tumors demonstrating a combination of neuroendocrine features and glandular formation were first described in a series of 12 patients in 1974.17 The authors proposed the term “goblet cell carcinoid” to reflect the combined histology, but the term adenocarcinoid refers to the same entity. Of note, in the original description, 9 of the 12 patients were treated with appendectomy alone, and only 1 of the 12 developed recurrent disease. Interestingly, the only patient to develop recurrent disease in this series underwent a right hemicolectomy as opposed to a simple appendectomy.17

In the recent SEER review of appendiceal tumors, goblet cell carcinoid (GCC) composed between 14% and 19% of all appendiceal tumors.4–6 Generally, the prognosis falls between that of classic carcinoid and adenocarcinoma, with disease-specific survival of nearly 75% at 10 years.6 However, the behavior of GCC can be quite diverse, leading some authors to subdivide these tumors into different groups. Surprisingly, GCCs lack staining for S100 (present in typical appendiceal carcinoids), suggesting they may not arise from subepithelial neuroendocrine cells as do typical carcinoids.14 This discrepancy in the cell of origin may help explain the difference in prognosis between goblet cell and typical carcinoids.

In another review encompassing 10 years of data from the National Cancer Database, carcinoid tumors were separated into typical carcinoid, GCC, composite goblet-cell carcinoid–adenocarcinoma (CGCC-A), and other neuroendocrine carcinomas based on ICD-O-3 codes.18 GCC patients were diagnosed at a later age than typical carcinoid patients (52 vs. 41 years),18 potentially as a consequence of the different cells of origin. Results of this study also mirrored prior studies in suggesting that GCCs are significantly less likely than typical carcinoid to have lymph node metastases, yet are associated with a slightly worse prognosis than typical carcinoid. Five-year overall survival was 77.6% for GCCs as compared to 86.3% for typical carcinoids.18 In contrast, CGCC-A tumors were much more likely to be associated with both nodal and distant metastasis when compared to GCCs, and carried a 5-year overall survival of 56.3%.18

In another study that attempted to subclassify GCCs, Tang et al reviewed 63 GCCs in a single institution, separating the tumors into GCC Group 1, adenocarcinoma ex-GCC signet ring type (Group 2), and adenocarcinoma ex-GCC poorly differentiated (Group 3).19 While the 3-year disease-specific survival was 100% in the first group, it declined to 85% in the second, and 17% in the third, emphasizing the differences among the spectrum of GCC tumors.19 Survival was not closely linked with stage of disease in all cohorts. In Group 1, one-third of patients (10 of 30) had stage IV disease; the single patient with stage IV disease who died during follow-up survived 119 months after diagnosis. In Group 2, 23 of 26 patients had stage IV disease at diagnosis; 4 were alive with no evidence of disease at last follow-up (including 1 patient who presented with stage IV disease), and 15 of 26 were alive with disease with median follow-up of approximately 3 years. In contrast, in Group 3, all seven patients had stage IV disease; six of the seven patients died of disease in 2.5 years of mean follow-up.19

A source of confusion that has arisen with this classification system described in the paper by Tang et al was the use of the signet ring name to describe a tumor that is quite distinct from mucinous adenocarcinoma with signet ring features. The latter diagnosis carries one of the worst prognoses of all appendiceal tumors, while that of adenocarcinoma ex-GCC signet ring type carries an intermediate prognosis. However, the authors did note that the majority adenocarcinoma ex-GCC signet ring tumors were p53 negative. This is in stark contrast to conventional colonic adenocarcinoma, which is most commonly p53 positive, possibly suggesting a different phenotype.19 Overall, this appears to be an informative series as the histologic subtype was closely associated with metastatic behavior and prognosis.

Generally, in the absence of distant metastasis, right hemicolectomy is considered the optimal management of appendiceal GCC without regard to the size of the tumor. Once again, definitive guidelines are difficult to establish given the rarity of the diagnosis and lack of prospective studies. One meta-analysis reviewing management of appendiceal GCC included data from 100 patients with adenocarcinoid. They noted a 7% failure rate among patients undergoing appendectomy, as compared to 10% with partial colectomy.20 The authors suggested that right hemicolectomy provides no therapeutic benefit to patients. However, the patients who underwent colon resection may have had tumors with higher risk features. Furthermore, an unpublished series of 70 primary appendix cancers from Memorial Sloan Kettering revealed a low risk of LNM from GCC or adenocarcinoma of the appendix (13% and 28%, respectively). Patients with absence of LNM had a very low risk of subsequent recurrence compared to those with LNM (9% vs. 82%, p < 0.0001). Therefore, right colectomy offers important staging and prognostic information. Given that LNM were not common, it is unlikely that the small Varisco meta-analysis would have been able to demonstrate a statistically significant survival difference. It is highly doubtful that a prospective trial will be conducted to resolve this question; in the meantime, right hemicolectomy remains the appropriate management course for these patients.

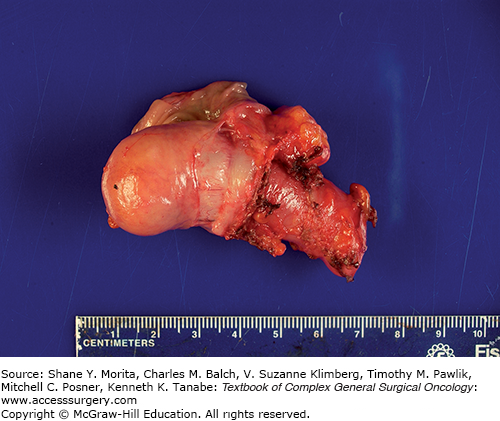

A dilated, mucin-filled appendix may occur in a variety of conditions, the majority of which are benign when the dilation is less than 2 cm (see Fig. 105-1). The term mucocele is often used to refer to any condition in which the appendix is dilated and filled with mucin; some authors discourage the use of the term mucocele in these circumstances, as it gives no indication of the underlying cause.21,22 The mucin-filled appendix can be a consequence of obstruction of the appendiceal lumen by a hyperplastic polyp or serrated adenoma (benign processes), or due to neoplastic growth in the wall of the appendix such as a mucinous adenoma/cystadenoma, mucinous lesion of uncertain malignant potential, or even due to a mucinous adenocarcinoma.22

The potential for apparently benign processes such as a mucinous adenoma to lead to pseudomyxoma peritonei seems counterintuitive, but likely occurs because of inconsistencies in pathologic classification. Some pathologists will reclassify benign appearing lesions as malignant if there is evidence of cellular extra-appendiceal mucin, while others prefer to use the term “low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm (LAMN)” for both.23 Those lesions with benign histologic appearance that are completely excised (negative margin at the appendiceal base with no gross or even microscopic perforation, and no mucin in the right lower quadrant at surgical exploration) carry an extremely low risk of recurrence. In combined results of two large reviews of appendiceal mucinous neoplasms, none of the 66 patients with a nonperforated appendix subsequently developed peritoneal disease.23,24 However, even without evidence of perforation or overt peritoneal disease at the time of appendectomy, malignant mucinous neoplasms resected with a negative margin can recur in the form of pseudomyxoma peritonei (see Fig. 105-2). The lack of a thorough pathologic analysis might also contribute to underdiagnosis. Insufficient sectioning of the appendix may result in failure to note an area of fibrosis where perforation may have occurred.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree