The management of patients with hematologic disorders in pregnancy involves a multidisciplinary approach involving specialists from hematology, obstetrics, and anesthesiology. Whereas regional anesthesia has led to a decline in maternal morbidity and mortality, the presence of uncorrected coagulopathy or the use of anticoagulant or antithrombotic medications pose a special risk for the rare complication of an epidural hematoma after neuraxial anesthesia. This article briefly reviews the common principles of anesthesia for obstetric patients, provides an obstetric anesthesiologist’s perspective on the implications of regional anesthesia in obstetrics, and enhances communication between the specialties.

Overview of obstetric anesthesia

Introduction

Anesthetic management of the obstetric patient with hematologic disease requires establishing a plan for anesthesia that incorporates the patient’s specific hematologic problem, the comorbidities, and the obstetric situation. The increasing popularity of regional anesthesia in the last several decades has greatly changed the experience of labor. Whereas the use of regional anesthesia has aided in decreasing maternal morbidity and mortality, a new dimension to the evaluation of hematologic issues and the increased awareness of maternal thrombophilias has led to the present widespread use of various anticoagulant medications in the pregnant population. Moreover, the increasing rate of cesarean delivery has resulted in an increased incidence of placental implantation abnormalities with resultant maternal hemorrhage concerns. This discussion briefly reviews the common principles of anesthesia for obstetric patients, provides an obstetric anesthesiologist’s perspective on the implications of regional anesthesia in obstetrics, and enhances communication between the specialties.

Principles of General Anesthesia for Cesarean Delivery

When general anesthesia is required for cesarean delivery, a rapid sequence technique is typically used whereby an intravenous induction agent (most commonly sodium thiopental [Pentothal] or propofol) and the paralytic agent succinylcholine are given in quick succession, followed by endotracheal intubation using cricoid pressure to prevent passive regurgitation of the stomach contents. Anesthesia is maintained using a volatile inhalation anesthetic agent, with the addition of nitrous oxide after umbilical cord clamping to minimize the concentration of volatile agent and the risk of uterine atony and postpartum bleeding. Parenteral opioid boluses or intravenous opioid patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) are used for postoperative pain management.

The incidence of cesarean deliveries has increased in the past decade and accounts for almost 40% of all deliveries in some countries. The relative risk of maternal mortality is greater with general anesthesia compared with neuraxial anesthesia because general anesthesia is more commonly performed in the presence of underlying comorbidities or obstetric complications. Approximately 25% of cesarean deliveries are done in an urgent or emergent manner for maternal or fetal indications. In these situations, general anesthesia may still be required to achieve rapid anesthetic depth for surgery and to prevent maternal or fetal compromise. The presence of uncorrected coagulopathy or the use of anticoagulant or antithrombotic medications may also necessitate the use of general anesthesia. Major concerns of general anesthesia include difficult airway management, risk of maternal awareness, depressant effects of inhalation anesthetics on uterine tone and the ensuing postpartum hemorrhage, and drug effects on early fetal alertness and later fetal neuronal development.

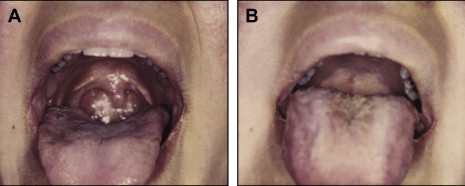

Maternal mortality has decreased dramatically in the last 50 years, due in large part to the widespread adoption of neuraxial anesthetic techniques. The regional anesthesia use for cesarean delivery was 55% in 1981 compared with 84% in 1992. This change in practice has paralleled the decline in maternal mortality related to anesthesia. An analysis of the liability claims between the years 1990 and 2003 compared with claims pre-1990 showed that respiratory causes of injuries decreased from 21% to 4%. During this time, the claims for maternal nerve injury and maternal back pain increased significantly. The incidence of failed tracheal intubation in the pregnant population is 8 times higher than in the nonpregnant population (up to 1 in 250) and can be unexpected. Pilkington and colleagues examined the maternal airway and found a 34% increase in the incidence of the most difficult airway classification (Mallampati 4, Samsoon modification) when comparing their airways at 12 and 38 weeks’ gestation. These changes have been attributed to pregnancy-related fluid retention, weight gain, and breast enlargement. The process of labor and delivery can further worsen airway edema, making airway instrumentation even more difficult ( Fig. 1 ). Coupled with the pregnancy-related increase in oxygen consumption and decrease in functional residual capacity, these patients are at a high risk of arterial oxygen desaturation during apneic episodes. This risk is exaggerated even further in morbidly obese patients and those with preeclamsia and multiple gestations.

Although gastric emptying of liquids does not seem to decline during pregnancy and labor, the reduction in lower esophageal sphincter tone and cephalad displacement of the stomach by the gravid uterus increases the risk of gastroesophageal reflux disease during pregnancy. According to the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) task force on preoperative fasting guidelines, the ingestion of clear fluids is allowed throughout labor and up to 2 hours before a scheduled surgical procedure but oral intake of solids should cease at least 6 hours before elective cesarean delivery.

Principles of Regional Anesthesia

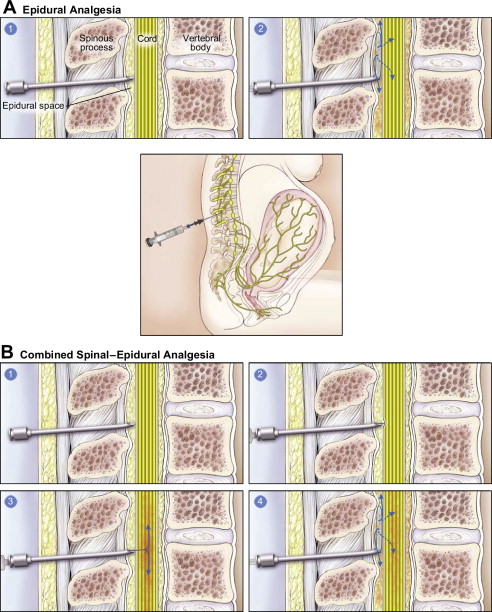

Neuraxial techniques such as spinal, epidural, and combined spinal-epidural (CSE) can be used both for pain relief during labor as well as surgical anesthesia during cesarean delivery. The choice of technique depends on patient factors, the need for speed and reliability of onset, the ability to titrate and redose via a catheter-based technique, and individual preference. Spinal anesthesia relies on the deposition of local anesthetic (usually in combination with an opioid) into the cerebrospinal fluid. This technique is quick, reliable, provides excellent surgical anesthesia, and uses a small gauge (25 gauge) pencil-point needle for administration. The disadvantages of spinal anesthetics are the risk of hypotension from rapid onset of sympathectomy and vasodilation, as well as a limited duration of action (typically 1–2 hours). Epidural anesthesia is performed by placing a catheter in the epidural space, with the option for continual infusion or intermittent boluses through the catheter ( Fig. 2 A). Epidural anesthesia is slower in onset and associated with less hemodynamic instability compared with spinal anesthesia. The presence of a catheter allows for titration of medication dose as well as readministration of local anesthetic for the duration of labor and for prolonged surgical procedures. The catheter can also be left in place for postoperative pain management or when the risk of bleeding requiring reoperation is a concern. The disadvantages of this technique include occasional inadequate spread of the anesthetic and the increased risk of venous injury and epidural hematoma formation with the use of a larger-gauge needle (17 gauge or 18 gauge). The use of neuraxial techniques in a parturient with hematologic disease may be precluded by uncorrected coagulopathy or when the risk of epidural hematoma outweighs the benefit.

Physiologic Changes of Pregnancy: Epidural Vein Dilation

The epidural space contains a venous plexus that becomes distended during pregnancy, labor, and delivery. During routine spinal and epidural placement, puncture of this plexus can lead to venous bleeding. The accumulation of blood in the epidural space can lead to compression of spinal cord and spinal nerves, with potential for permanent neurologic deficits if the compression is not relieved within 6 to 12 hours.

Regional Anesthesia for Cesarean Delivery

Neuraxial technique is the most common method of anesthesia for cesarean delivery. For most elective cesarean deliveries, a single injection of local anesthetic and opioid is given through a pencil-point spinal needle (eg, 25-gauge Whitacre needle) with a typical duration of anesthesia of 1 to 2 hours depending on the drug and dose. If a longer surgical procedure is anticipated (ie, previous abdominal surgeries and risk of adhesions, abnormal placental implantation, maternal obesity), a CSE technique is often done. This technique is performed by first identifying the epidural space using a 17-gauge or an 18-gauge epidural needle. A longer spinal needle is then inserted in a needle-through-needle technique to reach the subarachnoid space and deposit the intrathecal dose of medication (see Fig. 2 B). An epidural catheter is then placed into the epidural space, which allows for subsequent dosing with additional local anesthetic or opioid medication, if necessary. In women who have an epidural catheter in situ for labor analgesia and later require a cesarean delivery, the epidural can be extended to surgical anesthesia by using a higher potency local anesthetic such as 2% lidocaine. Additional advantages of using regional anesthesia for cesarean delivery include the ability of the mother to be awake and alert for the infant delivery, the presence of a partner in the operating room, and the ability to include a long-acting opioid such as morphine in the subarachnoid or epidural injection to provide up to 18 to 24 hours of postoperative pain relief.

Regional Anesthesia for Labor and Vaginal Delivery

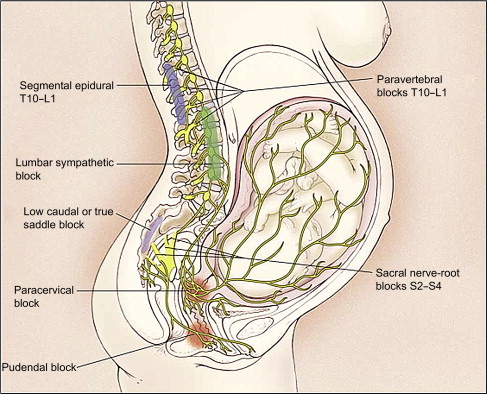

Labor pain is caused by uterine contractions and cervical dilation. These pain impulses are transmitted through the lower thoracic, lumbar, and sacral nerve roots and are amenable to epidural blockade ( Fig. 3 ). In 2006, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the ASA issued a joint statement indicating that maternal request is a sufficient medical indication for pain relief. An increasing number of women are choosing lumbar epidural to alleviate labor pain, which allows for the continuous infusion of a dilute local anesthesia solution, opioid, or both into the lumbar epidural space. The use of epidural analgesia during childbirth varies from region to region, but approximately 60% of women in the United States and the United Kingdom choose this form of pain relief. Studies have confirmed the increased analgesic efficacy of epidurals compared with parenteral opioids. Although the use of labor analgesia can prolong the duration of labor by approximately 1 hour, concerns about the use of epidurals during labor leading to increased incidence of cesarean delivery have not been substantiated. The 2006 ACOG opinion statement reaffirms the notion that “the fear of unnecessary cesarean delivery should not influence the method of pain relief that women can choose during labor”. Contraindications to the use of regional anesthesia include patient refusal, increased intracranial pressure, some preexisting neurologic disorders, hemodynamic instability, local or systemic infection, frank coagulopathy, and the use of anticoagulant or antithrombotic medications. The latter two hematologic contraindications are the focus of this article.

Alternative Methods of Pain Control for Labor and Vaginal Delivery

Labor pains can lead to increased maternal blood pressure, increased catecholamine release, and hyperventilation. Although epidural analgesia has been shown to be the most effective form for pain relief in labor, some women may choose alternative forms of pain control. The other modalities of pain control include psychoprophylaxis (Lamaze method), transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation (TENS), inhalational analgesia using nitrous oxide (rarely used in the United States but popular in other countries), systemic opioids, various hypnotic techniques, and immersion in water. The administration of intravenous opioid using a PCA system has been associated with higher patient satisfaction compared with intermittent opioid boluses given by the provider. Parenteral opioids rapidly cross the placenta and appear in fetal circulation. The potential for neonatal respiratory depression must be considered if parenteral opioids have been administered.

Complications of Neuraxial Analgesia and Anesthesia

Epidural analgesia and anesthesia are generally safe, but serious complications can occur. The complications of nerve injury, postdural puncture headache, epidural abscess, and meningitis are not reviewed in this article. Epidural hematoma is a rare complication, but patients with underlying hematologic disorders are at an increased risk and the sequelae are potentially catastrophic. Management of obstetric patients with impaired clotting function can therefore be challenging for the anesthesiologist and the hematologist.

Epidural hematoma

Symptoms of acute spinal hematoma include sharp radiating back pain with a radicular component and sensory and motor deficits that outlast the expected duration of spinal or epidural anesthesia. Neuraxial hematologic complications in the obstetric population are rare. A retrospective study of severe neurologic complications after the use of central neuraxial anesthetic technique in Swedish obstetric patients between 1990 and 1999 estimated the risk of hematoma after obstetric epidural to be 1:200,000. Ruppen and Derry identified 27 studies including a total of 1.4 million obstetric patients and determined the rate of epidural hematoma to be 1 in 168,000 and the risk of persistent neurologic injury to be 1 in 237,000. None of the cases with persistent neurologic injury were clearly attributed to epidural hematoma. A UK prospective study noted that the incidence of complications of epidural and CSE anesthesias were at least twice those of spinal and caudal anesthesias. In another comprehensive literature review, Loo and Dahlgre identified 7 cases of spinal hematoma after labor epidural (through 1998) and 3 patients with risk factors for bleeding, including 1 patient with abnormal activated prothrombin time (aPTT) and 1 with cholestasis of pregnancy and abnormal coagulation profile. Although anticoagulation therapy with low-molecular-weight-heparin (LMWH) is considered a risk for development of epidural hematoma, there are no case reports of epidural hematoma in an obstetric patient on enoxaparin or other anticoagulant medications. However, spontaneous epidural hematoma has been described in the obstetric population, including 1 case in a patient being treated with enoxaparin, 60 mg subcutaneously twice daily, for antiphospholipid syndrome.

Anesthesia for Patients with Hemoglobinopathies

Sickle cell disease and thalassemias are the 2 largest and most significant groups of hemoglobinopathies. The perioperative management of patients with sickle cell disease includes confirmation of preoperative diagnosis, clinical assessment, prevention, and management of postoperative complications. Acute sickle cell crises have been reported to occur in 16.9% of patients after cesarean delivery and hysterectomy. Principles of anesthetic management include maintaining oxygenation, hydration, thermoregulation, and acid-base regulation. The use of regional anesthesia may reduce pain-induced respiratory splinting and improve oxygenation in these patients. Adequate lateral tilt positioning is critical in these patients because venous stasis owing to vena caval compression by the gravid uterus may contribute to a sickle cell crisis.

Patients with thalassemia are classified by whether the α or β chain production is affected. Clinical severity varies with differing genotypes. For those with severe anemia and extramedullary hematopoiesis, bony abnormalities of maxillofacial area can complicate airway access. Most patients with thalassemia carrier state present with mild microcytic anemia, and their anesthetic care is uneventful.

Anesthesia for Patients with Preexisting Coagulopathy

Thrombocytopenia

Following injury to blood vessels, platelets play an important role in establishing the initial hemostatic plug and subsequent activation of the coagulation cascade. A low platelet count may impair surgical hemostasis, leading to an increased risk of hemorrhage and anesthetic complications, such as epidural hematoma. The most common causes of thrombocytopenia in pregnancy include gestational thrombocytopenia, preeclampsia, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, and collagen vascular disorders. Other rare causes include May-Hegglin anomaly, Bernard-Soulier syndrome, and Glanzmann thrombasthenia.

Anesthesia management of patients with thrombocytopenia

The prevalence of mild thrombocytopenia (a platelet count <150 × 10 9 /L) was recorded in 6.6% of patients in a large obstetric center over a 7-year period. The approach to a patient with thrombocytopenia begins with a thorough review of history that may reflect a bleeding disorder, such as symptoms of menorrhagia, epistaxis, prolonged bleeding following dental procedures, and previous history of unanticipated blood transfusion. It is also important to elicit medication use that may affect platelet function, including nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, aspirin, and some herbal medications. The physical examination may be significant for mucocutaneous bleeding, splenomegaly, petechiae, ecchymoses, or excessive bleeding around the peripheral intravenous sites. However, pregnancy may make the physical examination somewhat unreliable because some signs, such as epistaxis, bleeding gums, or easy bruising, may be associated with normal physiologic effects of pregnancy. A high index of suspicion for DIC should exist in obstetric situations including placental abruption, massive hemorrhage and transfusion, intrauterine fetal demise, and amniotic fluid embolism (AFE).

There is a wide range of opinion, with little actual evidence, regarding the safe lower limit of platelet count for neuraxial anesthetic techniques. In a survey in 1996, all respondents stated that they would insert an epidural if the platelet count was greater than 100 × 10 9 /L, only 16% of academic and 9% of private anesthesiologists would do so if the platelet count was 80 to 99 × 10 9 /L, and only 2% and 0% would if the platelet count was 50 to 79 × 10 9 /L. The most recent (2007) ASA practice guidelines for obstetric anesthesia do not comment on a specific platelet count that is considered safe for neuraxial anesthesia. There are insufficient data to assess whether a routine platelet count can predict anesthesia-related complications in uncomplicated parturients. Platelet count is clinically useful for those with suspected pregnancy-related hypertensive disorders or other disorders associated with coagulopathy.

In addition to the absolute platelet count, adequate platelet function should be considered in determining if neuraxial anesthesia can be delivered safely. In preeclampsia, platelet function has been shown to be abnormal despite a normal platelet count, the mechanism of which remains unclear. Yuen and colleagues reported on a case of epidural hematoma for a patient with severe preeclampsia after epidural placement for cesarean delivery. Her platelet count at the time of anesthetic intervention was 71 × 10 9 /L, an increase from 49 × 10 9 /L from the time of admission. One hour after cesarean delivery under epidural anesthesia, the patient developed hypertension and an unusual tonic-clonic seizure that was generalized but spared her lower limbs (which had a motor and sensory deficit from the L1 dermatome downward). A 4-mL clot extending from T12 to L2 level was discovered on computed tomographic scanning. When thrombocytopenia occurs in the context of preeclampsia, other coagulation parameters may also be abnormal. Conversely, in a case series of 7 deliveries in 3 sisters with the May-Hegglin anomaly, no adverse neurologic sequelae were noted. Neuraxial techniques (5 epidurals and 2 spinals) were used in deliveries in all 7 patients with platelet counts ranging from 14 × 10 9 /L to 100 × 10 9 /L. Several case series have documented the use of neuraxial techniques in patients who had thrombocytopenia (platelet count <100 × 10 9 /L) without any adverse neurologic effects. However, these individual experiences cannot be extrapolated to all patients, and the overall clinical picture, rather than the absolute platelet count, is important in determining the risk of epidural hematoma in these patients.

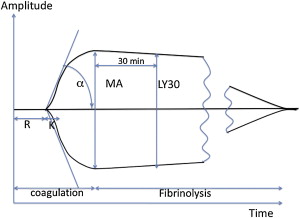

There is no single test of coagulation that can be used to predict the bleeding risk. As a bedside test of whole blood anticoagulation, thromboelastography (TEG) may become a useful tool in helping the anesthesiologist determine the coagulation and fibrinolysis function in certain obstetric situations ( Fig. 4 ). TEG was first established in 1941 and popularized for the use of coagulation monitoring during cardiac and liver transplant surgeries. TEG has been used to demonstrate the hypercoagulable state of normal pregnancy as well as the impaired coagulation that develops in the setting of severe preeclampsia. A significant correlation was found between the maximum amplitude (an indicator of clot strength) and platelet count in healthy term parturients. Preliminary studies suggest that TEG may be a sensitive test to detect the decline of enoxaparin in patients after stopping therapy, with an in vitro correlation of increased TEG R-time (time to initial clot formation) and anti-Xa activity. The platelet function analyzer (PFA-100, Dade Behring, Deerfield, IL, USA) is an alternative bedside assay of coagulation that specifically evaluates platelet function and may be a superior assay for the detection of abnormal platelet function in severe preeclamptic patients. The information obtained from TEG or PFA-100 may be used in conjunction with usual coagulation tests to determine if adequate coagulation is present before any surgical or anesthetic intervention.