Anal cancer accounts for 3% of all lower gastrointestinal tract malignancies in the United States.1 It is predicted that 8080 new cases of anal cancer will be diagnosed in the United States in 2016, with this the disease will account for 1080 deaths.1 Of the estimated cases of anal cancer in 2016, 5160 cases will occur among women and 2920 among men, a 1.7-fold higher number of cases among women.1 Squamous cell carcinomas (SCC) comprise the overwhelming majority of anal tumors although other rare histologic subtypes include adenocarcinoma, melanoma, neuroendocrine, and sarcoma.2 In this chapter, the term anal cancer will refer to anal canal SCC, unless otherwise specified. Anal cancer is classified as a human papillomavirus (HPV)-associated cancer and accounts for 15.6% of all new HPV-associated cancers diagnosed annually.3

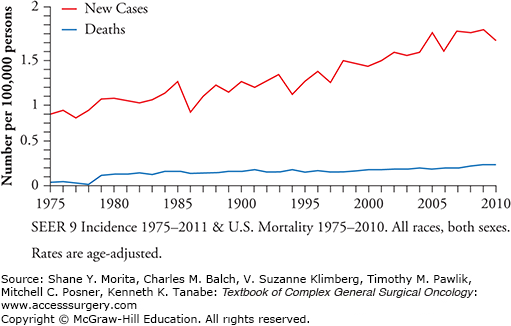

The incidence of anal cancer has increased significantly in the past 30 years, jumping 160% in men and 78% in women4,5 (Fig. 116-1). When examined by gender and race, white females (2.6 per 100,000) and black males (2.1 per 100,000) have the highest annual incidence rates and Asian/Pacific Islander men and women (0.3 per 100,000 and 0.5 per 100,000, respectively) have the lowest.3 The incidence of anal cancer also increases with age. The age-adjusted Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) incidence rates in 2010 were 1.1 per 100,000 and 5.8 per 100,000 for those diagnosed before the age of 65, and 65 or older, respectively.6

The overall 5-year survival rate for anal cancer is 65.6%;6 however, this varies considerably by stage at diagnosis (79.6% for local disease; 59.8% for regional disease, and 31.3% for distant disease at diagnosis).6 The age-adjusted death rate for patients with cancer of the anus, anal canal, and anorectum is approximately 0.2 per 100,000 per year6 with an average age at death of 66 years old.7

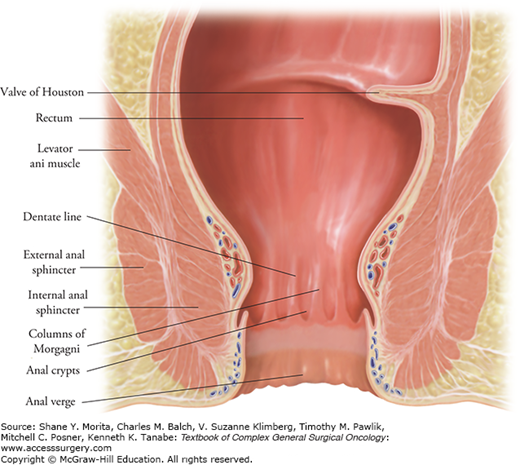

The anus represents the distal-most portion of the gastrointestinal tract and consists of a glandular mucosa-lined anal canal and an epidermis-lined anal margin. It is helpful to divide the anal canal by anatomic landmarks to allow for more precise localization of lesions and treatment planning. The surgical anal canal is defined as extending from the anorectal ring (a palpable landmark representing the upper level of the anal sphincter complex) to the anal verge8 (Fig. 116-2). The mucosa of the proximal anal canal is of endodermal origin and has lymphatic drainage to the perirectal (mesorectal and superior rectal) and internal iliac (hypogastric) nodes. The mucosa of the distal anal canal is of ectodermal origin and has lymphatic and venous drainage to the femoral lymph node basin. The latter area has sensory innervation from the somatic nervous system via the pudendal nerve branches. The dentate (pectinate) line separates the two anal canal zones and represents a visible transition zone where the mucosa changes from columnar to cuboidal epithelium and becomes darker red in color. From proximal to distal, the mucosa gradually and progressively changes from cuboidal to transitional epithelium until it finally becomes squamous epithelium. Distal to the dentate line, the squamous mucosa begins to acquire features of normal skin such as hair and apocrine glands at a mucocutaneous junction referred to as the anal verge or margin. The anal verge marks the terminal aspect of the anal canal and is a key landmark in differentiating between anal canal and anal margin (perianal skin) cancers.

Historically, HPV-associated cancers and precancerous lesions of the vulva, vagina, cervix, anus, and penis had disparate nomenclatures and histopathological classifications. In 2012, the CAP-ASCCP Lower Anogenital Squamous Terminology (LAST) Standardization project proposed a unified nomenclature across groups and serves as the most current terminology for HPV-associated squamous proliferations including anal neoplasia. The recommended two-tiered nomenclature consists of high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) and low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL), which may be further subclassified into corresponding levels of anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN). For example AIN 1 corresponds to anal LSIL and AIN 2 and AIN 3 to anal HSIL.9

Minimally invasive squamous carcinoma of the anus is termed superficially invasive squamous cell carcinoma (SISCC) and is described as microinvasive disease that is amenable to conservative or excisional treatment and has low risk for metastasis. In the anal canal, the suggested definition of SISCC includes a completely excised lesion with invasion less than 3 mm from the basement membrane and with less than 7 mm in horizontal spread. Invasive cancers are described as lesions larger than SISCC and generally require more aggressive treatment.10

The distinction between anal canal and anal margin cancers can be difficult, as lesions often involve both areas at the time of diagnosis. In general, SCCs that arise from the mucosal surface of the anus are treated as anal canal cancers even if they involve the perianal margin. Those tumors that arise within the hair-bearing skin distal to the mucocutaneous junction are termed anal margin or perianal skin cancers and tend to behave biologically like cutaneous squamous malignancies.11 The term Bowen’s disease refers to intraepithelial neoplasia of the perianal skin.

As with the cervix, the cytologic classification of SIL of the anus is reported with increasing severity as atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS), LSIL, ASC suggestive of HSIL (ASCH), and HSIL.12

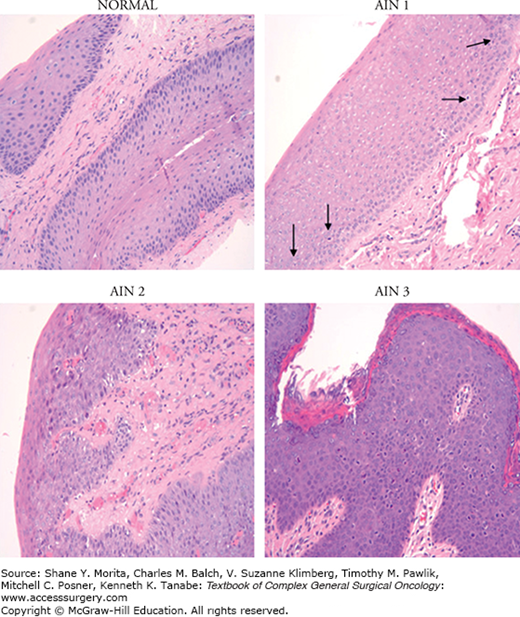

Squamous intraepithelial lesion is generally characterized by a loss of epithelial stratification and nuclear polarity as well as nuclear polymorphism, hyperchromatism, and increased mitotic activity. SIL may also be associated with the presence of koilocytes, which are enlarged cells with a cytoplasmic halo surrounding the nucleus and indicative of active HPV replication. LSIL is defined as the replacement of 20% to 30% of the epithelium by abnormal cells, while in HSIL abnormal cells replace more than half of the epithelium13,14 (Fig. 116-3).

Figure 116-3

Premalignant histology—normal: Squamous epithelium exhibits good maturation. There are rare nonatypical mitotic figures located at the base within the proliferative layer of the epithelium. This is a normal finding. AIN 1: There are an increased number of mitotic figures but they are limited to the lower third of the squamous epithelium (arrows). AIN 2: There is retarded maturation with several mitotic figures occurring through the middle third of the squamous epithelium. The squamous cells in the upper layer are plump with large size nuclei and less cytoplasm when compared to the normal epithelium. AIN 3: There is complete lack of maturation, with atypical mitoses found through the upper third of the squamous epithelium. The cells exhibit increased nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio and the nuclei show nuclear membrane irregularities and perinuclear halos (“popcorn” appearance). (Used with permission from Dr. Domenico Coppola, Tampa, FL.).

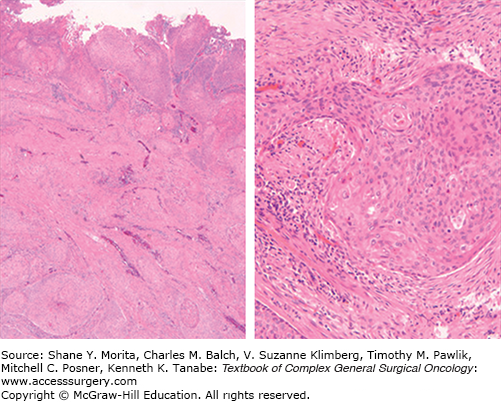

Squamous cell carcinomas of the anal canal may have a homogeneous cellular composition but often show a mixture of areas with different histologic features. Nonetheless, these cancers appear to behave similarly despite variable morphologic appearances. Previously, anal canal cancers have been characterized as keratinizing, nonkeratinizing, and basaloid (also termed junctional or cloacogenic) subtypes,14 but the value of these distinctions have been questioned. However, poor keratinization, basaloid features (small to moderate amounts of cytoplasm and eosinophilic necrosis in the center of nests), and small tumor cell size have been associated with oncogenic high-risk HPV infection (Fig. 116-4). Given significant interobserver variability, the small size of diagnostic biopsies not representative of the entire tumor, and the lack of proven prognostic impact of different histologic features, it is generally recommended that the generic term “squamous carcinoma” be used for these tumors, with the inclusion of a comment describing any distinct, observed histopathologic features (e.g., size of predominant neoplastic cell, basaloid features, degree of keratinization, and adjacent AIN).

FIGURE 116-4

Anal cancer histology: The tumor is ulcerated and shows nests of neoplastic squamous epithelium with single-cell keratinization as seen at high power. There is intervening stroma and tongues of tumor infiltrating smooth muscle and surrounded by desmoplastic stroma. The tumor cells are oval to polygonal with eosinophilic cytoplasm. Occasional intercellular bridges between tumor cells are observed (high power). There are mitotic figures and the nuclei are relatively uniform in the tumor depicted here, but they can be pleomorphic. (Used with permission from Dr. Domenico Coppola, Tampa, FL.)

Infection with HPV is likely a critical cause of anal cancer, but in isolation it is likely insufficient.15 HPV is a small DNA tumor virus with over 100 different genotypes identified, of which at least 30 HPV genotypes are sexually transmitted and infect the anogenital tract.15 HPV genotypes are classified according to the likelihood of causing cancer. HPV-16 is the only HPV type with sufficient evidence to support classification as “carcinogenic” for anal cancer,15 whereas there are 13 HPV genotypes deemed carcinogenic for cervical cancer. Anal cancer is thought to progress from an HPV infection that has deviated from natural viral lifecycle and promotes the development of preneoplastic anal intraepithelial lesions (LSIL, HSIL).

A meta-analysis of (a number of series including) 955 anal cancers reported that the overall prevalence of HPV was 84.3%. The HPV-16 was the predominant type (73.4%), followed by HPV-18 (5.2%), and HPV-33 (4.8%); a few (6.8%) had multiple viral types.16,17 HPV prevalence in SIL is similar to invasive anal cancer (92% in LSIL and 94% in HSIL) with more HPV types detected.16 HPV prevalence in anal squamous neoplasia are similar to those found in cervical cancers, thus reflecting similar anatomy and, in particular, the presence of a mucosal transformation zone, a preferential site for HPV infection.15

In general, risk factors for anal cancer are closely related to those of HPV exposure, such as sexual promiscuity, anal receptive intercourse and homosexuality (specifically for males), as well as those affecting immune status, such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and use of immunosuppressant medication. Additional risk factors for anal cancer include age, smoking history, and a history of cervical dysplasia or cancer in women. There are well-established populations that are considered at high-risk for anal cancer, including those infected with HIV (men and women) and men who have sex with men (MSM); therefore, special emphasis is placed on these high-risk groups. Table 116-1 presents the risk factors for SIL and anal cancer, highlighting differences in risk across populations.

Summary of Risk Factors for Anal SIL and SCC

| Risk Factor | SIL | Anal SCC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | Risk Estimate | Population | Risk Estimate | |

| HIV | Women28,42 | 7.8–33 | Women28,42 | 6.8–14.5 |

| Men42 | 20.8 | Men39,42 | 14–26.7 | |

| MSM28 | 60 | MSM28,39,40 | 80–100 | |

| Higher number lifetime female sex partners | Men19–21 | 2.5–3.9 | ||

| Higher number lifetime male sex partners | MSM18 | 3.3 | MSM19 | 5.6–17.6 |

| Women21 | 2.6–15.9 | |||

| Receptive anal intercourse | Women21,28 | 2.0 | Women21 | 1.6–2.1 |

| MSM27 | 2.4 | MSM19,21 | 5.6–17.6 | |

| HIV+48 | 4.3 | |||

| HIV+ MSM26 | 5.6 | |||

| Cervical HPV, any type | Women62 | 2.0–4.5 | ||

| Cervical SIL/Cancer | Women63,19 | 1.9–10 | Women64 | 2.3–10 |

| Anal warts | HIV+ MSM48 | 2.8 | Women19–21 | 5.1–115 |

| Men48 | 6–8 | |||

| AIDS diagnosis | HIV+ MSM42 | 80 | HIV+ MSM42,50 | 3.8–30 |

| Low CD4 count | HIV+ MSM44 | 14.4 | HIV+ MSM49 | 14 |

| Transplant patient | Solid organ transplant53 | 11 | Renal ransplant37,52,53 | 4.5–14.4 |

| Duration of immunosuppression (≥10 years) | HIV37 | 133.4 | ||

| Solid organ transplant37 | 19.9 | |||

| Smoking | HIV+ MSM18 | 2.3–3.5 | Men/Women21,61 | 2–4 |

| Older age | HIV+ MSM44 | 3.1–4.8 | HIV+ MSM39 | 1.3 |

| Women62 | 1.3 | |||

In general, higher numbers of lifetime sexual partners increase the risk of anal SIL and anal cancer in both men and women.18–21 Early case-control studies reported over a 30-fold increased risk for anal cancer among men who ever had receptive anal intercourse (HIV status unknown);22 however, more recent studies report risk estimates between 5.6 and 17.6.19,21,22 Anal cancer rates among HIV-negative MSM are comparable to those for cervical cancer in women (5 per 100,000 person years).23 In prospective studies, 5% to 15% of HIV-negative MSM had an incident SIL detected by cytology within a 2 to 4 year period.24,25 The risk of anal cancer associated with receptive anal intercourse among women was lower than that among men, with Daling et al21 reporting an OR = 2.1 (95% CI 1.3 to 3.3) and several others reporting no association.19,20 Receptive anal intercourse also increases risk for SIL21,26–28 (Table 116-1). Anal HPV infection is strongly associated with receptive anal intercourse, with between 1.6 and 3.8 increased risk.29–34 HPV has been detected in the anal canal in both men and women who reported never engaging in receptive anal intercourse,26,33–35 suggesting alternative modes of transmission.19,29

Immunosuppressed patients, particularly HIV-positive or organ transplant patients, account for approximately 20% to 35% of patients diagnosed with anal SCC. The risk of anal cancer among immunosuppressed patients is highest among those with HIV/AIDS (standardized incidence ratio (SIR) = 28.75 – 81.1) compared to organ-transplant patients (SIR = 4.85 – 14.4).36,37 Anal cancer is a significant burden for the HIV-positive population, being the fourth most common cancer among those infected with HIV.38 In a meta-analysis of nine studies, the pooled incidence rate for anal cancer was 46 per 100,000 person-years among HIV-positive MSM compared to 5.1 per 100,000 and 2 per 100,000 person-years for HIV-negative MSM and the general population, respectively.23 HIV-positive MSM have over an 80- to 100-fold increased risk of developing anal cancer,28,39,40 and a 60-fold increased risk of dysplasia compared to their HIV-negative counterparts.41 HIV-positive women and heterosexual men are also at an increased risk for SIL and anal cancer28,39,42 (Table 116-1). HIV-positive MSM frequently have existing HSIL (37% to 57%) upon first examination, while HSIL is less common in HIV-positive women (11% to 26%) and HIV-positive heterosexual men (15% to 17%).23,25,32,43 Among HSIL-negative HIV-positive MSM, over 50% had a new HSIL detected within 2 to 4 years, regardless of CD4 count or HAART treatment.44 Incidence of anal cancer among the HIV-positive population is increasing at higher rates than among the HIV-negative population, with an increase from 1% to 28% for anal cancer in HIV-positive men in 1980–1984 to 2001–2005, respectively.45

Risk factors for HSIL among HIV-positive men include older age, low pretreatment CD4+ cell counts, receptive anal intercourse, smoking, HPV-16 or HPV-18 infection and history of HPV-associated disease (e.g., warts), duration of immunosuppression, and AIDS diagnosis.18,42,44,46–48 Anal HPV-16/18 infection is strongly associated with progression to HSIL (OR = 31; 95% CI 5.7 to 169.6).44 Risk factors for anal cancer among HIV-positive MSM are low CD4 counts, AIDS diagnosis, and older age.28,39,42,49–51 The association between HAART treatment and ASCC is unclear. HAART does not reduce risk of anal cancer, and some early reports suggest incidence rates of anal cancer are significantly higher in the post-HAART era (after 1996) among HIV-positive MSM, compared to the pre-HAART era (77.8 per 100,000 vs. 21.8 per 100,000 person years, respectively).23

As with HIV-positive individuals, immunosuppressed organ or bone marrow transplant patients appear particularly susceptible to infection-related cancers, including anal cancer. A recent population-based study in Denmark among patients with end-stage renal disease reported an anal cancer incidence ratio of 19 (95% CI 11.2 to 34.7).52 In the United States, incidence ratio for anal cancer among solid organ transplant recipients was 5.4 (95% CI 4.4 to 6.6) and 11.6 (95% CI 8.7 to 15.2) for carcinoma in situ.53 Risk of cancer increased with increasing duration of immunosuppression.37 Renal transplant patients who were immunosuppressed for an average of 92.8 months (range 1 to 381) had an HPV prevalence of 21.3% and SIL prevalence of 5.8%,54 which is similar to an earlier report among long-term immunosuppressed renal transplant patients.55 Factors associated with risk of SIL among transplant patients were receptive anal intercourse, history of genital warts, and duration of immunosuppression.54 Prevalence of anal HPV-16, HPV-18, HPV-6, or HPV-11 in liver transplant patients 3 weeks posttransplantation was reported at 18%,56 which is similar to overall HPV prevalence in liver and kidney transplant patients within 24 hours of transplantation (29% and 21%, respectively).57 There does not appear to be an increased risk for anal cancer among allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients, which is in contrast to increased incidence of oral and cervical cancers.58,59

Cigarette smoking has been inconsistently associated with anal SIL and anal cancer (Table 116-1). Among MSM, even smoking was associated with persistent HPV infection in one study;60 however, this was not replicated.18,30,31,33 Among HIV-positive MSM, smoking status and duration were significantly associated with a 2.3- to 3.5-fold increased risk of HSIL, controlling for carcinogenic HPV and other confounding factors.18 With regards to the risk of anal cancer posed by smoking, two early case-control studies with unknown HIV status reported that current smoking was statistically associated with a two- to fourfold increased risk of anal cancer;21,61 however, these findings may be confounded by sexual practice and HIV status.

Women who have previously tested positive for cervical HPV are at a 2- to 4.5-fold increased risk of developing an anal SIL.62 In addition, a history of cervical SIL or cancer is a significant risk factor for anal SIL (OR = 1.9–10).19,63,64 Previous anogenital warts are also a strong risk factor for anal SIL and cancer for both genders19–21,48 and among HIV-positive MSM.48

The predominant carcinogenic mechanisms in anal neoplasia have been ascribed to the effects of the HPV onco-proteins E6 and E7, which have growth-stimulating and transforming properties.65 Classically, the integration of HPV DNA into the host genome results in a disruption in the E1–E2 region of the viral genome which, in turn, results in a loss of E2 protein function, with a subsequent uncontrolled expression of E6 and E7.66 The E6 protein binds to the p53 protein (an important mediator in cell cycle, DNA damage, and apoptotic pathways) and promotes its degradation, which is functionally equivalent to an inactivating mutation of this gene.67 The E7 oncoprotein functions via the formation of inactivating complexes with the important tumor suppressive cell cycle regulator, pRb, which leads to an increase in cell proliferation and genomic instability.67 Of these two viral oncoproteins, E7 has been shown to be the more potent oncogene in anal cancer, similar to HPV-associated cervical and head-and-neck cancers.68 In particular, there is a direct correlation between the level of chromosomal instability and the degree of E7 overexpression in cervical dysplasia.69 In cervical cancer, surrogate biomarkers of HPV infections have been defined as overexpression of p16 and loss of either p53 or pRb.70 Several small studies have confirmed this biomarker pattern in anal cancer.71–74

Similar to cervical carcinogenesis, there is a well-described progression from normal anal mucosa to SIL (LSIL-HSIL) and finally to invasive anal SCC. However, unlike cervical cancer, the molecular changes that occur during the progression to anal cancer have not been thoroughly investigated. Information can be gleaned from animal models75 and human tissue studies to elucidate some of the molecular biology of HPV-associated anal carcinogenesis. In animal models, forced expression of HPV E6 and E7 in anal epithelium was able to induce AIN, but additional chemical exposures were required for progression of AIN to invasive carcinoma.75 In such animal models, HPV E7 appears to play a dominant role in anal carcinogenesis.68 Alteration of cellular proteins and pathways, specifically loss of TGF-β and activation of the AKT-MTOR pathway, promoted growth of AIN and invasive anal cancer in one-third of mice tested,76,77 and inhibition of AKT using the mTOR inhibitor, rapamycin, delayed tumorigenesis.77 Biomarker analyses demonstrated that the activation of the AKT pathway in the invasive tumors was similar to that observed in human anal cancer.77,78

There is evidence that chromosomal aberrations, such as loss of heterozygosity (LOH) or microsatellite instability (MSI), are common in anal cancer; however, most studies included a small number of cases. In a small karyotype study of eight anal SCC, Muleris et al79 observed frequent deletions of chromosome 11q (n = 8) and 3p (n = 6). Heselmeyer et al,80 in a study of 23 anal SCCs, also showed LOH of 11q to be the most frequent (39%) alteration with chromosomal losses, mapping to 4p, 13q, and 17p, occurring less frequently. Gervaz et al81 performed an analysis of anal SCCs from 18 HIV-negative and 10 HIV-positive patients and demonstrated a similar frequency of 11q LOH across both groups (10 of 28; 38.5%). However, they also observed that the frequencies of LOH at the 5p (0% vs. 33%; p = 0.12), 17p (10% vs. 43%; p = 0.09), and 18q (41% vs. 0%; p = 0.05) loci tended to be less in HIV-positive compared to HIV-negative patients.81 There is also some evidence that LOH occurs in the progression to AIN,82 with one study reporting chromosomal gains in chromosome 3q.83 In summary, extrapolating from cervical cancer and consistent findings in anal tumors, the 11q23 region may harbor a putative tumor suppressor element, of which LOH may represent an early common event in HPV-associated anogenital carcinogenesis,81,84 regardless of HIV status. These findings suggest that, in addition to HPV infection, an accumulation of chromosomal changes, such as loss of 11q, is also required during the progression to AIN and invasive cancer.

In addition to the traditional genetic changes, there is a growing appreciation that epigenetic alterations, such as DNA methylation and chromatin remodeling, may play a critical role in the neoplastic progression of anal cancer. DNA methylation is the addition of a methyl group to a cytosine nucleotide when found in a cytosine-guanine dinucleotide pair (termed CpG locus). Clusters of methylated CpG sites in gene promoter regions (termed CpG Islands) are associated with transcriptional silencing. The silencing of genes, especially tumor suppressor genes, by DNA methylation is a common alteration that occurs in all cancers.85 There is emerging evidence that aberrant DNA methylation occurs in anal neoplasia. By single gene analyses, Zhang et al86 examined the methylation status of a panel of 11 genes. They noted that methylation of IGSF2 and DAPK1 was common in anal SCC and HSIL detected by cytology, but absent in LSIL and normal biopsies.83 Using an array-based assay that measured over 1500 CpG loci, Hernandez et al87 identified 20 genes with DNA methylation differences at CpG loci between normal anal mucosa, carcinoma in situ, and invasive anal cancers. Just as there may be key epigenetic changes that occur in the progression from AIN to malignancy, the growth and progression of the invasive cancers may also be associated with identifiable alterations in the epigenome. In a study of 121 anal cancer patients from the mitomycin C arm of the RTOG 98-11 trial,88 Siegel et al89 characterized the epigenomic signatures associated with low-risk (size <5 cm, N0; n = 62) versus high-risk (>5 cm, N+; n = 59) anal cancer. A total of 16 CpG loci were identified to be differentially methylated, including sites associated with the known methylated cancer-related genes, SALL3 and SFRP2.89

Bruland et al90 have also postulated that there may be identifiable molecular subtypes of anal cancer. Using gene expression microarray profiling of 13 HPV-16-positive/E7 mRNA-positive anal cancer specimens, they were able to identify two distinct groups that were predominantly characterized by the differential expression of HPV- and/or E2F-regulated genes. This would suggest that, even in the setting of documented HPV infection, there may be differential penetrance of the transcriptional regulation controlled by HPV E6 and E7.90

Despite generally favorable survival outcomes, there is clearly heterogeneity in the response to chemoradiation therapy among anal cancer patients. Furthermore, both the short- and long-term toxicities associated with therapy are significant. Consequently, the identification of predictive and prognostic biomarkers would be valuable to allow for more personalized application of therapy. There have been limited studies to identify predictive and prognostic biomarkers of anal cancer and a majority of the studies conducted are limited by sample size (<100 cases).91 Table 116-2 summarizes the most highly studied tumor biomarkers in anal cancer and the reported associations with anal cancer outcomes.

Summary of Frequently Measured Prognostic Biomarkers in Anal Cancer

| Biomarker | Total Studies | Marker Detection | Percent Tumors Positivea | Significant Finding Related to Prognosisb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p53 | 10 | IHC | 34–100% | High nuclear p53 expression associated with worse local control, shorter DFS, or relapse-free survival93–95 |

| p16 | 4 | IHC | High p16 expression associated with longer relapse-free survival and longer OS94 | |

| Ki67 | 3 | IHC | 65% | Higher Ki-67 associated with longer DFS100 |

| p21 | 3 | IHC | 65–71% | Loss of p21 associated with shorter OS and higher locoregional failure rate96,97 |

| EGFR/HER-1 | 6 | IHC/FISH | 55–100% | NS |

| BCL-2 | 3 | IHC | 24–58% | Higher Bcl-2 associated with better local control and longer DFS92 |

| MVD/CD31 | 3 | IHC | 50–51% | NS |

| MiBl | 2 | IHC | 34–41% | Higher MiBl associated with longer colostomy-free survival98 |

| Cyclin D1 | 2 | IHC | 33–34% | NS |

| VEGF | 2 | IHC | 100% | NS |

Surrogate HPV biomarkers p53 and p16 have been examined as predictive and prognostic markers for anal cancer. Overall, p53 is the most comprehensively studied biomarker within 10 studies of varying sample size. Overall, only three of these studies suggested an association between elevated p53 expression and worse local control,92 DFS,92,93 or relapse-free survival.94 P16 staining, which is diagnostically informative as a biomarker of HPV activity, was not associated with anal cancer prognosis in three studies.90,95 However, in a study of 153 ASCC patients treated with standard radiation, 5-FU and MMC, p16 expression correlated strongly with relapse-free survival (relapse rate 27% in moderate/strong p16 vs. 62.5% in p16 absent/weak, p = 0.0076).94 In addition, median survival was 65.2 months (95% CI 46.0 to 84.4) among p16-positive cases as opposed to 22.3 months (95% CI 9.1 to 35.6) in p16-negative cases (p < 0.001).94 Other biomarkers within the p53 and pRb pathways have also been examined. There have been three studies of p21 expression (65% to 71% in tumors), of which two reported that loss of p21 may be associated with worse locoregional control96 or overall survival.97 Only one of three studies that examined bcl2 reported a significant association with improved tumor control and DFS.92 Among four relevant studies, Ki67 proliferative index was associated with superior colostomy-free survival (p = 0.04)98 and increased DFS (p = 0.03).95 Biomarkers such as EGFR, VEGF, and microvessel density have failed to demonstrate any association with clinical outcomes,91,94,99,100 while others (e.g., NFkB, M30, Cyclin A, PCNA, MCM7, SHH, and Gli-1)91 are associated with very limited data.

Interest in the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) pathway in anal SCC has increased due to the promise of EGFR pathway-targeted therapies in other SCCs. In anal cancer, EGFR has consistently been reported to be overexpressed.94,101–104 In a study of 84 patients, 34% of cases had increased EGFR copy number;102 however, others have reported no evidence of amplification104 or of EGFR mutations.103 In a study of neoplastic progression, expression of EGFR increased with increasing severity of AIN and was higher in HIV-positive patients.72,104 Notably, K-ras mutant cancers are generally insensitive to EGFR inhibitors, such as cetuximab. In five studies of anal cancer, very few to no mutations in K-ras were reported in primary or recurrent tumors.94,102–105 The consistent expression of EGFR in anal cancers and lack of mutations in EGFR, K-ras, and PI3K suggest there is potential for EGFR-inhibiting agents in the treatment of anal SCC,103 similar to the biomarker profile in EGFR-responsive HPV-positive head-and-neck SCC. Initial phase I and II clinical trials have evaluated the addition of cetuximab to cisplatin, 5-FU, and radiation regimens for locally advanced anal SCC.106–108 The initial phase I107 and the subsequent ACCORD16 phase II106 trials, both restricted to HIV-negative patients, were closed early due to dose-limiting acute and long-term toxicities. Neither trial examined EGFR or K-ras status prior to randomization. Early findings from two ongoing phase II trials, one in immunocompetent patients (ECOG 3205) and one in HIV-positive patients (AIDS Associated Malignancies Clinical Trials Consortium 045), reported severe toxicities in 2 out of 28 patients.108 The addition of cetuximab to standard 5-FU, mitomycin, and radiation has not been investigated.

The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system for anal cancer takes into consideration the characteristics of the primary tumor and involvement of the regional lymph nodes. In anal cancer, the T category is primarily determined by the size of the primary tumor (T1–T3), while direct invasion of any adjacent organ is classified as T4 disease. With respect to lymph node involvement, there are three separate N categories based on the lymph node chain involved (Table 116-3). Current staging guidelines have changed the staging of anal margin cancers from the previous AJCC TNM skin system to that of the anal canal.

AJCC Anal Cancer Staging and 5-Year Overall Survival Rates

| Primary Tumor | |

| T0 | No tumor |

| Tis | Carcinoma in situ |

| T1 | Tumor 2 cm or less |

| T2 | Tumor between 2 cm and 5 cm |

| T3 | Tumor larger than 5 cm |

| T4 | Tumor invades adjacent organ (not including anal sphincter) |

| Lymph Nodes | |

| N0 | No lymph nodes metastasis |

| N1 | Metastasis in perirectal lymph nodes |

| N2 | Metastasis in unilateral internal iliac and/or inguinal lymph nodes |

| N3 | Metastasis in perirectal and inguinal lymph nodes and/or bilateral internal iliac and/or inguinal lymph nodes |

| Metastasis | |

| M0 | No distant metastasis present |

| M1 | Distant metastasis present |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree