1.1 Introduction

The knowledge base underpinning the public health nutritionist professional is developed over years and built on a foundation of biology, biochemistry, physiology and basic nutritional sciences, as well as an understanding of social anthropology. The development of the foundations is not within the scope of this book. Many of these competencies are covered in the accompanying textbooks, particularly the Introduction to Human Nutrition and Nutrition and Metabolism. The aims of this book are to cover the skills needed in public health nutrition and to provide a coherent structure to enable the reader:

- to identify nutrition-related public health problems relevant at the local, regional, national and international levels

- to identify causes of these problems

- to develop strategies to deal with these problems

- to evaluate the impact of these strategies

- to understand the process whereby research-based evidence provides a basis for the development of public health policy

- ultimately, to improve nutrition-related health by applying evidence to action to solve problems.

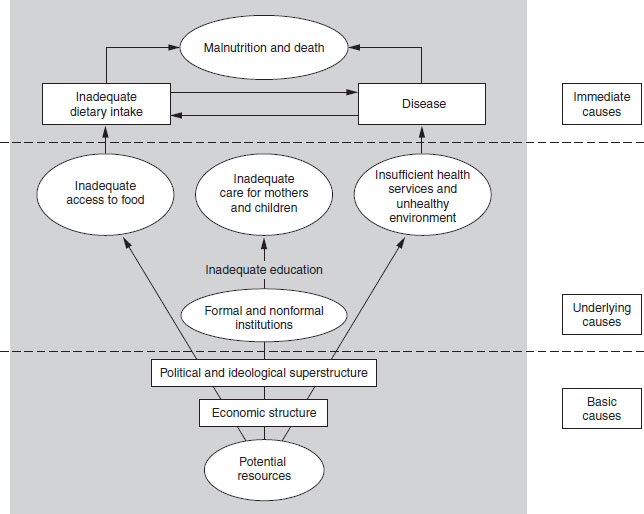

Public health nutrition is about applying knowledge to the solution of nutrition-related health problems. Often when confronted with a problem, people do not know where to start, become lost in the detail, and sometimes miss the obvious and simple critical steps that will really make a difference. In this introductory chapter an attempt is made to provide a framework for the reader to think logically and systematically: to provide a template to proceed in a logical and systematic way. People often want to jump in with what they think is the solution to the problem confronting them; the aim here is to help readers to think before they jump. It is now fashionable to talk about an evidence-based approach to public health. All this really means is finding out what others already know, putting aside one’s prejudices, assessing the situation objectively, and coming up with the best and most effective solution. It may seem obvious, but there is no need to fix that which is not broken. Rather, the effort should be to try to identify the key rate-limiting step (or major constraint to behavior) in the causal pathway and fix that. Our knowledge as to what the rate-limiting step is can never be perfect, so some judgment is required. However, the more systematically the evidence is gathered and reviewed, both in terms of the causal pathway and in terms of effective interventions, the more effective the effort will be in achieving the targeted health gains. The aim of this book is to give the student the knowledge and skills to think clearly about how to solve problems. The primary purpose of good nutrition is to maintain health and well-being. Nutrition is more than the food supply: it reflects the interaction between what we eat, and the metabolic demands of the body to maintain functional capacity. The basic, underlying and immediate causes of malnutrition are summarized in Figure 1.1. If nutrition is only thought of as the supply side of this balance this is likely to lead to a misunderstanding of the key rate-limiting steps that link good nutrition to wellbeing. It is also important to consider the social as well as the biological context within which individuals live and interact in society. While it is beyond the scope of this text to cover all aspects of whole-body integrated metabolism, some understanding of the underlying mechanisms that link diet and style of living to health is required to understand whether the lifestyle changes that are being suggested to improve health make sense biologically. Inevitably, good nutrition-related health is about understanding the relationships between the biological and sociological context within which individuals live and interact in society. Where food supply is limited there is a clear biological imperative to obtain enough to eat; where supply is in excess, social imperatives that restrain or limit behavior come into play. In all societies, especially those in transition, there is a complex mix of problems of overnutrition and undernutrition occurring in close proximity. The job of the public health nutritionist is to try to understand this complexity and to provide guidance as to what is best for most people. This book aims to help students in this task.

Figure 1.1 United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) conceptual model.

1.2 Organization of the book

There are 22 chapters in this book. The first eight chapters are designed to develop the skills required to understand how to identify and subsequently to develop approaches to address the major nutrition-related public health problems. Chapter 2 on nutritional epidemiology addresses the skills required for the design of appropriate studies, for conducting nutritional surveillance and the development of research protocols. It also reviews the analytical skills required in the use of nutritional and other relevant data and databases including the statistical issues, sampling study size and power, determination and application of appropriate statistical analytical techniques. Chapter 3 defines and describes the tools used to assess nutritional status at the individual and population levels. The emphasis in Chapter 3 is on assessment of dietary intake. Chapter 4 describes the methods and approaches used to assess physical activity. Nutritional status embraces an understanding of the dynamic between supply and demands, and increasingly it is becoming clear that, particularly in terms of understanding energy balance, it is essential to assess both intake and expenditure, and factors that affect both. Identifying the problem is only the first step in solving the problem; Chapters 5 and 6 describe the approaches to developing effective interventions in groups and individuals, respectively and Chapter 7 describes how to develop and present dietary guidelines that communicate dietary advice in the most sensible way possible, once it is clear what is the required or optimal nutritional pattern or profile. There is considerable overlap in the approaches used, broadly, the aim should be to use that approach which is most effective for most people, or different approaches for different groups if there appear to be different constraints in subgroups. Understanding the constraints on behavior and factors affecting food choice is the subject of Chapter 8.

Chapters 9–14 describe different aspects of malnutrition. Chapters 9 (overnutrition) and 10 (undernutrition) describe the development of aspects of what might be termed macronutrient malnutrition, while Chapters 11–13 describe specific micronutrient malnutrition deficiencies. Increasingly, it is becoming clear that undernutrition and overnutrition occur in different groups of people in the same countries, and that macronutrient and micronutrient imbalances can occur in the same people. Chapter 14 describes the complex area of eating disorders, which lead mainly to undernutrition of both macronutrients and micronutrients, but with different causes, and tending to affect different groups within a society, from those described in Chapters 9–13.

Chapters 15–18 describe different aspects of maternal and child health; Chapter 15 focuses on aspects of cognitive development, Chapter 16 focuses on the importance of infant feeding, Chapter 17 focuses on adverse outcomes of pregnancy in relation to folate and related B-group vitamins, and Chapter 18 describes the concepts that underpin fetal programming. Taken together, these chapters highlight the importance of achieving the optimal nutrient supply at the critical time to enhance and maintain function. This may be considered a key part, or first step of a life-course approach, recognizing that what happens after certain critical events is constrained by these earlier events and interacts with current behavior. Current health and well-being cannot be fully explained by current behavior alone, and early events (programming, early exposure) influence the way in which an individual and society react to what appears to be the same exposure. This may be described as explaining the sources of heterogeneity within a population, which may be also a mix of different levels of the expression of genes, gene–nutrient and nutrient–gene interactions.

Chapters 19–22 describe the main chronic disease that affect large numbers of people around the world; Chapter 19 describes cardiovascular diseases, Chapter 20 diabetes, Chapter 21 cancer and Chapter 22 osteoporosis. Already these chronic diseases affect more people in developing than in developed countries, and it is likely that this will increase as the nutrition transition continues in developing countries and rates of chronic diseases decline in developed countries.

There is no specific chapter on communicable or infectious diseases; the impact of these is covered extensively in the chapters on undernutrition. The aim has been to use major health problems as a way of illustrating approaches and ways of thinking that should help the reader to think about how to understand and address specific problems.

1.3 Definitions used in public health

Public health nutrition

A public health nutrition approach focuses on the promotion of good health (the maintenance of wellbeing or wellness, quality of life) through nutrition and the primary (and secondary) prevention of nutrition-related illness in the population. Public health nutrition is built on a foundation of basic and applied sciences, operates in a public health context, and uses the skills and knowledge of epidemiology and health promotion. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines health as a state of complete mental, physical and social well-being, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity. Public health is defined as the collective action taken by society to protect and promote the health of entire populations. Alternatively, it can be defined as the art and science of preventing disease, promoting health and prolonging life through the organized efforts of society. Epidemiology provides a rigorous set of methods to study disease occurrence in human populations.

Public health

The approach to public health may be summarized as being either broad or narrow (Table 1.1).

The narrow approach

The narrow approach focuses on disease prevention and cost containment, with health defined as the absence of disease. The underlying theory is that the way in which individuals live their lives (what they eat, what they do, whether they smoke or drink or engage in risky behavior) is the main cause of disease, and that the motivation to change behavior is based on reducing risk at an individual level. The evidence base comes from clinical and molecular epidemiology; research is undertaken that identifies differences in risk factors, and on the basis of that information, advice is given to the public that if they change their behavior they will reduce their risk of developing the disease (cancer or heart disease, etc.). This approach links an individual’s own behavior to risk of disease. The burden of prevention and health promotion lies with the individual and it is seen as their responsibility to address their risk behavior. The approach is aimed at identifying immediate and obvious problems now and addressing them now. The disadvantage of the narrow approach is that it may miss fundamental threats within society that may be outside the individual’s control (basic and underlying causes such as the wider socioeconomic factors, education and access to services, environmental factors, and the overarching values in society).

The broad approach

The broad approach defines health as more than the absence of disease. It considers well-being in terms of mental and physical health and also includes a sense of having some control over your life. The approach links public health science with policy: the action and structures agreed by society aimed at improving and maintaining health. The underlying theoretical model is sociocultural; it focuses on the wider environment and seeks to understand the factors that enable individuals to make healthy choices, or inhibit them. The motivating concern is about addressing the underlying sociostructural factors such as poverty, global issues and structures at a local, regional, national and international level that affect health. The evidence base for a broad approach comes from epidemiology as well as other approaches more suitable to exploring the sociostructural context. The broad approach takes a more long-term view of causes and solutions, addressing structural issues in society that make it more difficult for individuals to make optimal choices. The disadvantage of a broad approach is that because the approach is so broad it may never address the key rate-limiting steps in a timely manner.

Table 1.1 Different approaches to public health

| Characteristics | Broad | Narrow |

| Major public health activities | Link public health science with policy | Cost-containment, disease prevention |

| Place of epidemiology | Balanced by other methods | Clinical and molecular epidemiology |

| Advantages | Long term, global | Short |

| Disadvantages | Risk of failure because of breadth | Miss fundamental threats |

| Define health | Foundations for health | Absence of disease |

| Underlying theory | Sociostructural | Lifestyle |

| Motivating concerns | Inequalities, poverty, global | Individual risks |

The broad public health approach has been taken up and developed by UNICEF into a conceptual model. The UNICEF model is now widely used, at least in research and development in developing countries1 (this term is used in the sense of gross domestic product, rather than social and cultural development, and is not meant to imply a hierarchy or judgment about better or worse than a developed country) (see Figure 1.1). This conceptual model acknowledges that while the immediate causes of undernutrition may be a lack of food, often coupled with a high burden of infection, the provision of adequate education and health care has an important impact on health. The provision of these underlying factors is determined by basic causes such as the resources that are available in a society, and decisions about how these resources will be used. The model acknowledges that dealing only with the immediate causes will never lead to long-term improvements, which are dependent on the societies’ view as to how resources will be used and distributed in society to maximize the health and well-being of all members of society. These arguments do not apply only to developing countries; how governments prioritize the use of taxation is a function of the underlying values of the society (as expressed through the election of governments that reflect the popular view); for example, the balance of spending priorities between education, health and defense, or priorities for agricultural policies that subsidize farmers but not manufacturing industry. Policy decisions as to the priorities on spending are complex and reflect a balance of tensions and pressures that often pull in different directions. Policy will be discussed in more detail later in this chapter.

In reality, in most countries there is a recognition that a narrow (individual and immediate cause oriented) approach needs to be balanced with addressing, at least to some extent, the basic and underlying (broad) causes. Most governments acknowledge that there are differences in health outcomes in different sectors of society and that state resources should be used to try to redress these differences. The food supply is regulated in all countries, even if the regulation is restricted to issues of food safety. Many of the first efforts in public health were about developing regulations to protect the public against the adulteration of staple foods. It has always been recognized that freedom of choice does not operate in a vacuum. Many countries have regulations about the accuracy of information contained in labels. There are few countries where the government does not intervene in the food supply to some extent, either through legislation to recommend the fortification of foods or to subsidize the production of some foods, such as in the Common Agricultural Policy in Europe and farming subsidies in the USA and elsewhere.

In developing a public health perspective it is important to balance the narrow with the broad. Striking the right balance is difficult and influenced by philosophical and political considerations. As a public health nutritionist, when trying to solve a local or national problem, it is important that both the narrow and broader determinants of behavior are considered and that it is not assumed that knowledge and individual choice are all that matters.

Recently, the UK Faculty of Public Health has agreed the key concepts that underpin public health. These reiterate to some extent the debate about broad versus narrow approaches to public health (Box 1.1). The key issues are a population approach to promoting and protecting health and well-being. They also highlight the importance of information.

Epidemiology

Nutritional epidemiology underpins Public Health Nutrition. This is covered in Chapter 2. It provides a scientific basis for the development of the evidence upon which public health action can be implemented. It also provides guidance on the approaches as to the best way to evaluate and monitor the effectiveness of programs designed to improve health. Epidemiology is the only setting in which it is possible to ask questions about what factors affect processes in the whole population. The questions that are asked in epidemiological studies need to emerge from metabolic and clinical research; it is important to have some sense of the underlying mechanisms and processes involved in the way the body seeks to maintain optimal function. It is also essential to understand that the biological processes that maintain functional capacity in humans do so in a wider context. As mentioned above, epidemiology is not the only source of information essential to a public health perspective.

- Surveillance and assessment of the population’s health and well-being

- Promoting and protecting the population’s health and well-being

- Developing quality and risk management within an evaluative culture

- Collaborative working for health

- Developing health programs and services and reducing inequalities

- Policy and strategy development and implementation

- Working with and for communities

- Strategic leadership for health

- Research and development

- Ethically managing self, people and resources

Health promotion

Health promotion is defined as any process that enables individuals or communities to increase control over the determinants of their health. The Ottawa Charter for health promotion (www.who.int/hpr/archive/docs/Ottawa.html) outlines an internationally accepted framework for health promotion that includes five approaches:

- building healthy public policy

- creating supportive environments

- developing the personal skills of the public and the practitioners

- reorienting health services

- strengthening community action.

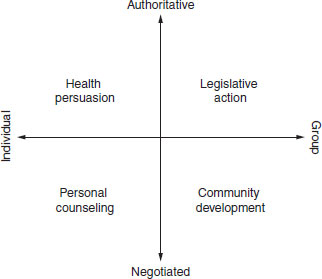

Figure 1.2 summarizes Beattie’s model of health promotion. This model further highlights the implications of the different underlying philosophical basis of public health discussed above. The two axes of the level at which promotion operates (individual to group/society) and the approach (authoritative to negotiated) highlight the range of options available. Often a range of approaches will be used. The key point is to use the approach that is going to be most effective and sustainable. In order to be effective, it is important that the strategy to be used has been shown to be effective in the target group, and that it addresses the most important constraints or rate-limiting steps, be they knowledge, attitudes, access or intentions. Understanding what the rate-limiting step is requires an understanding of the balance of factors that affect why people eat what they eat (see Chapter 8). In some circumstances, a legislative approach, which requires no action at the individual level, may be the most effective way to achieve the desired health gain. A simple example is the decision to fortify flour in the USA with folic acid (see Chapter 17).

Figure 1.2 A model for health promotion. Reproduced from Beattie (1981) with permission from Thomson Publishing.

Nutbeam and Harris (1999) have summarized the theoretical models that underpin a health promotion approach. It is beyond the scope of this chapter to review all the models and theories described, and they are covered in more details in Chapters 5 and 6. The main point to emphasize here is that at whatever level one operates, there is a theoretical model that has been developed and should be considered as a basis for organizing the planning of work. A summary of models relevant for the different levels at which health promotion works is shown in Table 1.2.

A health promotion planning and evaluation cycle has been described and involves seven steps:

- problem definition

- solution generation

- resource mobilization

- implementation

- impact assessment

- immediate outcome assessment

- outcome assessment.

For all but the last step in the cycle, theories have been developed as to how to perform each step most effectively: to identify targets for intervention; to clarify how and when change can be achieved in targets, and how to achieve organizational change and raise community awareness; to provide benchmarks against which actual can be compared with ideal programs; and to define outcomes and measurements for use in evaluation. The precede–proceed model is another way that has been used to encapsulate the steps in a health promotion cycle and this will be described in more detail in Chapter 6. These ideas have been taken and used as a basis for the development of the public health nutrition cycle, which is described in more detail later in this chapter.

Table 1.2 Summary of models relevant for the different levels at which health promotion works (from Nutbeam and Harris, 1999)

| Area of change | Theories or models |

| Theories that explain health behavior change by focusing on the individual | Health belief model |

| Theory of reasoned action | |

| Transtheoretical (stages of change) model | |

| Social learning theory | |

| Theories that explain change in communities and community action for health | Community mobilization: Social planning Social action |

| Diffusion of innovation | |

| Theories that guide the use of communication strategies for change to promote health | Communication for behavior change Social marketing |

| Models that explain changes in organizations and the creation of health-supportive organizational practices | Theories of organizational change Models of intersectoral action |

| Models that explain the development and implementation of healthy public policy | Ecological framework for policy development Determinants of policy making Indicators of health promotion policy |

1.4 What are the key public health problems?

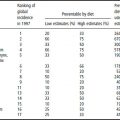

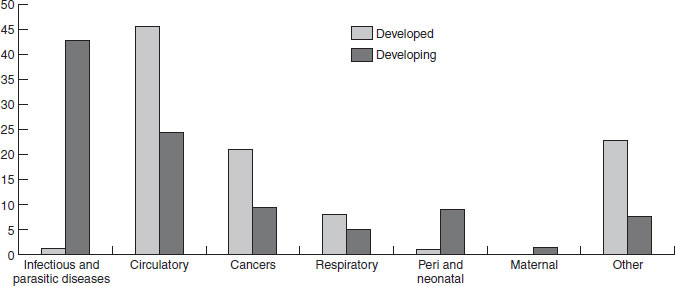

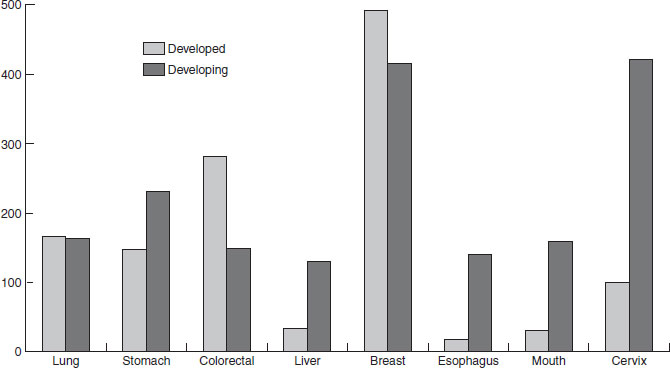

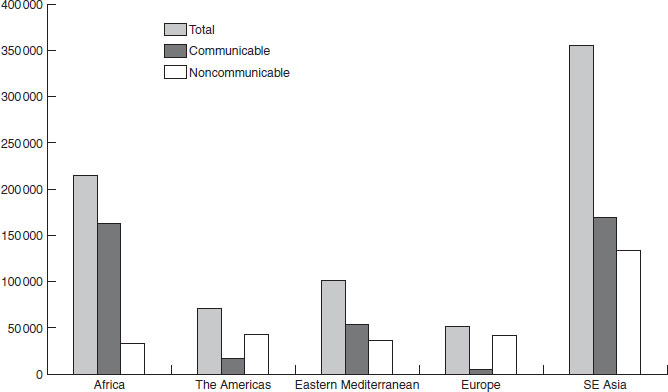

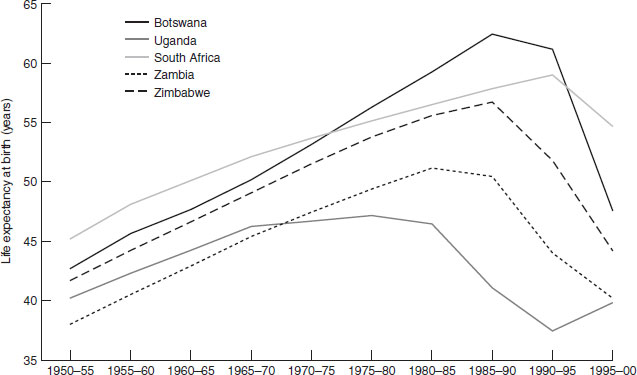

The chapters in the latter part of this book cover in detail the public health problems that have the greatest public health impact. Here, the aim is to give a broad overview of the overall balance of global nutrition-related health problems, and to highlight, in particular, the double burden of both overnutrition and undernutrition that many transitional countries suffer (Figures 1.3–1.6, Table 1.3; http://www.who.int/whr/previous/en/). Data are presented in two ways, which are important to distinguish; Figures 1.3 and 1.4 present the proportion of deaths attributable to each major cause, whereas Figure 1.5 and Table 1.3 show the absolute numbers of deaths or disease burden. From a public health perspective the total burden of disease gives a sense of the demands placed on the health services and infrastructure. Figure 1.3 and 1.4 show the burden of infectious diseases in developing countries compared with developed countries; Table 1.3 shows the high burden of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) in sub-Saharan Africa. Although cancer, as a percentage of overall deaths, is lower in developing than developed countries, in absolute terms (Figure 1.4) more people die of cancer in developing countries. In Africa and south-east Asia (Figure 1.5) the burden of communicable diseases is high, compared with Europe; in south-east Asia the burden of noncommunicable diseases is nearly as high as communicable diseases and is also higher than in Europe. The higher burden of cancer in developing countries may be a function of both a higher underlying incidence and poorer case finding and treatment (owing to limited access to health facilities). The impact of HIV on overall mortality and life expectancy is illustrated in Figure 1.6, which shows that in a number of African countries life expectancy has actually fallen since the late 1980s, after a steady rise from the 1950s to 1985.

In addition to the burden of death and disability the burden of chronic undernutrition is heavy in many developing countries. It is a stark figure, but 14 000 children die every day from malnutrition-related causes. Among those who survive, the effects on growth and development are profound and long-lasting. A quarter of all babies born in south Asia weigh less than 2500 g at birth (UNICEF, http://www.unicef.org/statis/2001). In India (44%) and Africa (29%) many children are underweight, while the proportion of the adult population becoming obese is also rising. Food insecurity continues to be a major problem for many people around the world, and not just in developing countries (see http://www.euro.who.int/ Nutrition for European data and http://www.nlm.nih.gov/pubs/cbm/nutritionsummit.html#51 for US data). The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) provides a great deal of information about the nutrition situation in most countries (http://www.fao.org/es/esn/nutrition/profiles_en.stm). More details about the burden of undernutrition are covered in Chapter 10.

Figure 1.3 Percentage distribution of causes of death. Reproduced with permission from the WHO. (http://www.who.int/whr/previous/en/).

Figure 1.4 Burden (number per 1000) of cancer in developed and developing countries (women). Reproduced with permission from the WHO. (http://www.who.int/whr/previous/en/).

Figure 1.5 Burden of disease in diability-adjusted life-years by WHO Region. Reproduced with permission from the United Nations Population Division. (http://www.who.int/whr/previous/en/).

Figure 1.6 Changes in life expectancy in selected African countries with high HIV prevalence, 1950–2000. Reproduced with permission from the United Nations Population Division.

The double burden of problems of communicable and noncommunicable diseases, related to malnutrition (overnutrition and undernutrition) in the widest sense, was extensively described by Popkin (2002), who summarized the stages of the health, nutritional and demographic transitions (Figure 1.7). Many countries in the developing world have subpopulations in different stages of these transitions, which makes national data difficult to interpret. The complexity also places a particular burden on health services with limited resources.

Table 1.3 Leading causes of mortality in sub-Saharan Africa, 1999

| Rank | % of total |

| 1 HIV/AIDS | 20.6 |

| 2 Acute lower respiratory infections | 10.3 |

| 3 Malaria | 9.1 |