Fuller Albright. (Photograph from March/April 1970 edition of the Harvard Medical Alumni Bulletin)

Fuller Albright was a giant in the field of endocrinology who made landmark contributions to the understanding of many diverse conditions, including postmenopausal osteoporosis, gonadal function, and Cushing’s syndrome [1]. However, he is best known for his investigation of calcium metabolism , the primary focus of his earlier career.

Albright was born in Buffalo, NY, on January 12, 1900. He attended Harvard College, followed by Harvard Medical School in 1921, and then completed his medical training in Internal Medicine at The Massachusetts General Hospital. Albright was mentored by Dr. Joseph Aub, a clinical scientist in endocrinology [1]. Between 1928 and 1929, Albright spent 1 year in Vienna studying under the pathologist Dr. Jacob Erdheim, who was credited with establishing the relationship between the parathyroid glands and calcium homeostasis [1]. It may have been during this time that Albright developed his interest in calcium metabolism .

In 1944, Dr. Albright gave the presidential address at the annual meeting of the American Society for Clinical Investigation [2]. He discussed the difficulties of clinical investigation, which he described as “trying to ride two horses—attempting to be an investigator and a clinician at one and the same time.” He warned of the “danger on one side that he, as a clinician, be swamped with patients” versus the danger that “he, as an investigator, be segregated entirely from the bedside.” Dr. Albright attained success as a clinical investigator by skillfully combining these two roles. In his lifetime, he had 118 scientific publications and was credited with being the first to describe 19 new syndromes or disease manifestations [3].

Dr. Albright offered advice for success in combining practice and the laboratory in his cartoon, which he titled “The Do’s and Do-Not’s along the road leading to the castle of success in clinical investigation” (Fig. 1) [2, 4]. His list of the ten “Do’s” included not only “measure something…make charts…[and] interpret data” but also such key elements as “look from all sides…[and] backing without strings.” Importantly, his “Don’t” list admonished against being “fooled by numbers” or a “slave to theory.” Albright followed these precepts dutifully. Upon his return to the Massachusetts General Hospital in 1929, he began work in the clinical investigation of calcium metabolism . He conducted experiments involving detailed measurements of dietary intake and urinary and fecal output to clarify metabolic pathways [1]. Dr. Albright understood the importance of precise measurements in clinical investigation. His meticulous calcium balance studies shed light on then little known pathways involved in calcium and phosphate metabolism, and on the effects of parathyroid hormone. Albright’s accomplishments are even more impressive, given the resources available for his studies in the 1920s. His investigations were limited to the measurement of calcium and phosphorus in blood, urine, and feces, and the use of a parathyroid hormone extract [5]. Assays for measurement of parathyroid hormone had not yet been developed nor would they be until the work of Berson and Yalow 40 years later [5, 6].

Fig. 1

Fuller Albright’s “Do’s and Do Nots” for a successful career in clinical investigation. (From [2]. Reprinted with permission from American Society for Clinical Investigation)

In a series of papers entitled “Studies on the physiology of the parathyroid glands,” Dr. Albright and his colleagues described the results of their detailed metabolism studies. One of the papers focused on a case of hypoparathyroidism [7] . Dr. Albright admitted a young man with presumed idiopathic hypoparathyroidism. The report charts measurements for every 8 hours of the 27-day study period. Fluid intake and output were reported along with calcium and phosphorus intake and output. Parathyroid hormone was administered to the patient four times. Dr. Albright and his coinvestigator, Dr. Read Ellsworth, observed that administration of parathyroid hormone led to an increase in serum calcium and a decline in serum phosphorus, and an increase in urinary phosphorus excretion. There was an initial decrease in urinary calcium excretion, followed by a sudden increase in excretion (once the serum calcium level reached approximately 8.5 mg/dL) [7]. Further experiments, with data collection every hour, were conducted to better elucidate the exact time course of these events, and showed that parathyroid hormone effects were evident within the first hour.

In another paper in the series, the effect of parathyroid hormone was explored in normal subjects [8]. Similar techniques were employed as in the prior study. Patients were admitted and maintained on a low-calcium diet. Measurements of calcium and phosphate intake and output were conducted over several days and the response to an infusion of parathyroid hormone extract assessed. The observations were similar: parathyroid hormone increased serum calcium levels, increased urinary calcium and phosphorus excretion, and lowered serum phosphorus levels. They did note that with significant hypercalcemia, a rise in phosphorus can be seen.

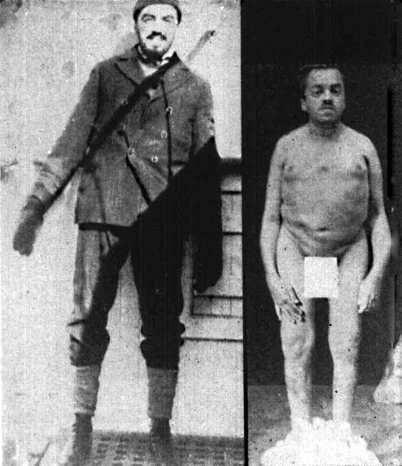

Dr. Albright later went on to apply these observations to patients with primary hyperparathyroidism . One of the earliest and surely the best-known cases of primary hyperparathyroidism involved the patient Captain Martell (Fig. 2). The picture highlights the dramatic effect of untreated primary hyperparathyroidism on the skeleton over the course of a decade. Fuller Albright played a key role in the studies on this patient, the results of which provided invaluable insight into the pathophysiology of primary hyperparathyroidism. Captain Martell first presented to Bellevue Hospital in New York City in January 1926 with loss of height and fractures [9]. In 1918, he was a 6-ft 1-in. merchant mariner. Over the course of the year, he lost height and developed a protruding chest. He also complained of muscle weakness and frequent “thick white gravel” in his urine [10]. By 1926, at age 30, he was 5’6” with the marked kyphosis shown in the right panel of Fig. 2, and he had suffered multiple fractures. He was hospitalized for over 2 months. Testing confirmed an elevated serum calcium, and metabolic studies confirmed excessive calcium excretion, well beyond his intake. Based on prior studies on the effects of administering parathyroid hormone to dogs, hyperparathyroidism was suspected. Dr. Albright noted that “the tentative diagnosis of an overproduction of parathyroid hormone (hyperparathyroidism) was made for the first time in this hemisphere, for the second time in the world” [9]. The patient was referred to Massachusetts General Hospital, where he was first under the care of Dr. Aub and Dr. Bauer, and later Dr. Albright. In 1948, when discussing this case, Albright noted that he did not mention his own name along with those of Aub and Bauer, not “because of modesty” but because he joined Dr. Aub’s group after the diagnosis was established [9]. While this may be true, it was Albright’s further metabolic studies that were instrumental in expanding the understanding of primary hyperparathyroidism .