Chapter 63 AIDS Psychiatry

THE ROLE OF PSYCHIATRIC ILLNESS IN HIV TRANSMISSION

Prior to the mid-1980s, the public was relatively unaware of the risk factors related to both contracting and transmitting HIV. As education improved, individuals learned to protect themselves by avoiding the risky behaviors well understood to transmit the virus.1,2 Historically, risk reducing measures have included screening donors and donated blood products, abstinence from sex or safe sexual practices, and using clean needles for injection drugs. Due to these public health efforts, much of the developed world understands the transmission routes and risk factors of HIV and AIDS. Despite this, vulnerable populations of people continue to engage in activities that place them at risk for contracting and transmitting HIV.

Individuals with severe mental illness (such as recurrent major depression, bipolar affective disorder, and schizophrenia) and substance abuse problems (also a psychiatric problem) make up a large part of this vulnerable population. Between 3% and 23% of adults with severe mental illness are HIV positive, compared to 0.6% of the population in the United States.3 Those with severe mental illness are at risk for contracting HIV through high-risk sexual and drug use behavior. A 1996 epidemiologic study of 2864 patients receiving medical care for HIV found a 1-year prevalence of ∼50% for psychiatric illness, with only 27.2% using a psychotropic medication.4 In the outpatient HIV clinic at Johns Hopkins Hospital (Moore Clinic), just over half of the patients who seek medical care have a major psychiatric disorder other than substance abuse (75% have a substance abuse disorder).5,6

Patients with HIV/AIDS and mental illness often lack the capacity to adhere to complicated medication regimens.7,8 Additionally, we now know that HIV infection carries its own psychiatric sequelae, such as AIDS mania and dementia, compounding the disease manifestations and containment efforts in certain patients. In effect, AIDS has become a psychiatric epidemic, in which those individuals at greatest risk of exposure to and spread of the virus are mentally ill patients who are unable to incorporate preventive, educational, or medical measures into their lives. Treatment of co-morbid psychiatric illness can improve patient care and therapeutic outcomes, effectively fighting the spread of the AIDS epidemic.

PSYCHIATRIC FORMULATION

A thorough psychiatric formulation, like its counterpart in any medical field, allows the physician to develop a comprehensive treatment plan that addresses all the problems of the patients, therefore increasing the chances of treatment success. Psychiatric diagnosis is limited by the lack of chemical, genetic, and radiological tests assisting in the placement of presenting signs and symptoms under a diagnostic label that guides evidence-based treatment. This situation makes a comprehensive formulation guiding overall treatment vital. One method of organizing the complicated clinical details which the patients present has been described.9 It is a formulation that involves looking at the details of a comprehensive history, mental state exam, and physical exam so as to develop a formula that encompasses four different vantages, or perspectives. Those perspectives are (1) the disease, (2) the dimension, (3) the behavior, and (4) the life story.

PSYCHIATRIC TREATMENT

The treatment plan for each patient must be informed by the following:

Unfocused, symptomatic treatment is less desirable than diagnostically driven treatment. For instance, providing anxiety-relieving benzodiazepines (like alprazolam) to treat a patient’s anxiety is far less productive than diagnosing a panic disorder (if it is present), educating the patient about it, and treating with an antidepressant (like sertraline). Understanding the patient and diagnosis creates the opportunity to evaluate the benefit of treatment compared with the side effects of the treatment. The process of illness education and discussion of risks and benefits of treatment is critical when developing a therapeutic alliance with the patient. The therapeutic alliance serves the purpose of bringing patients back to the clinic and promoting their adherence to the medications and other treatments prescribed.10,11

In many psychiatric conditions, available evidence supports a number of treatment options (like cognitive behavioral therapy, medication, or a combination of the two). There is no evidence that one antidepressant is more effective than others at treating major depression in HIV-positive patients. Therefore, clinicians have the option to initiate treatment with any approved antidepressant. Similarly, data often show similar success rates for medication and behavioral therapy-based treatment options. In panic disorder, the literature suggests that cognitive behavioral treatments, including exposure/desensitization therapy, and medications have similar efficacy.12–14 Combination treatment with cognitive behavioral therapy and medication may have even greater success.15 The availability of treatments may have a large impact on what is chosen for your patient. For instance, is cognitive behavioral therapy available for a patient with a depression or anxiety disorder and does his insurance cover it? Can he or she engage in therapy or make use of it? Does the treating clinician have time to provide the labor-intensive therapy? These questions realistically guide the psychiatric treatment.

MEDICATION INTERACTIONS

Decisions regarding medications require some understanding of the cytochrome P450 metabolism of both antiretrovirals and psychiatric medications. All antiretrovirals beside the nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) and fusion inhibitor, enfuvirtide, are metabolized by the CYP system. HIV protease inhibitors (PIs), such as lopinavir and ritonavir, typically inhibit the CYP 3A4 and 2D6 isoenzymes. Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs), including nevirapine and efavirenz, generally induce these same systems.16–20 Fortunately, in spite of these theoretical drug interactions, there are few clinically significant adverse reactions, likely because most medications utilize multiple metabolic pathways. At the same time, real increases in plasma concentrations may have little or no clinical impact as a result of the wide therapeutic indices of many medications. Many documented interactions involve ritonavir, which appears to be one of the most powerful inhibitors of the CYP 3A and 2D6 isoenzymes. The clinical relevance of most potential interactions remains largely unknown, necessitating the need for close observation of patients with co-administration of these drug classes.21,22 While this is an area that needs additional research, we are hopeful that the improved mental health and medication adherence that can result from the use of psychotropics outweighs the potential impact on antiretroviral blood levels.23

MAJOR PSYCHIATRIC SYNDROMES AND THEIR TREATMENT

Demoralization and Major Depression

Major Depression

In the HIV clinic, major depression may be harder to evaluate. Sadness, low mood, and feelings of illness are important descriptors, yet these are common symptoms in the chronically ill patient with HIV. It is often the anhedonia, that is, the loss of pleasure associated with pleasurable activities, that is most easily assessed. Patients will say that they no longer enjoy visiting family, or that sports are no longer interesting to them. Nothing seems to bring joy. Each patient must be asked what he or she ordinarily likes or enjoys, and patients with major depression will often say that these things have lost their interest or their usual pleasure.

Demoralization

Demoralization is best understood as an adjustment reaction to a stressful event. The chronological relationship to an event is not the distinguishing factor between demoralization and major depression. Many patients trace the start of a major depression back to a catalyzing event. The distinguishing factors are related to self-attitude changes, neurovegetative changes, and thoughts of death. In other words, when demoralized, a patient has low mood and some functional impairment yet lacks the defining characteristics of a major depression. Demoralized patients may report feeling ‘normal’ when their attention is diverted away from the inciting event. At the same time, they may become overwhelmed with grief or sadness when reminded of the distressful situation. Similarly, patients with demoralization are able to distinguish between their event-specific feelings of sadness and their own self worth.24 Demoralized patients retain the ability to find joy in usual activities if they are distracted from the inciting event or circumstances that led to their depressed mood. Patients with major depression have impairment in their ability to experience joy in any circumstances. Whereas major depression is a disease of the brain, demoralization is a disorder of mood based on circumstances.

Prevalence and Risk

In a study at the Hopkins Moore clinic, approximately one-half of HIV-positive patients with depressive symptoms suffered from major depression, while the other half experienced demoralization or adjustment disorder, as defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.25,26 Overall, studies have shown the prevalence rates of major depression in HIV-positive patients to be between 15%and 40%.27–29

Major depression is a risk factor for acquiring HIV. Epidemiologic data show a correlation between risky behaviors in HIV-negative individuals and higher scores on screening tools for psychological distress.30 Another study revealed a sevenfold increase in the lifetime prevalence of mood disorders among nonsubstance-abusing patients who presented for HIV testing when compared to the general population.31 Furthermore, researchers have clearly identified major depression as a risk factor for unsafe behaviors, such as substance abuse, that may lead to HIV infection.32–34

The literature has shown marked decreases in antiretroviral compliance among HIV-infected patients suffering from major depression compared to infected individuals who are free from mental illness.35,36 Treatment of co-morbid depression appears to improve adherence to antiretroviral regimens37 and therapeutic outcomes.38 Unfortunately, data show that over half of HIV-positive patients reporting a major depressive disorder do not receive antidepressant therapy.39 In one clinic study, early recognition and treatment of major depression with both pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy helped 85% of patients and restored half of them to baseline.40

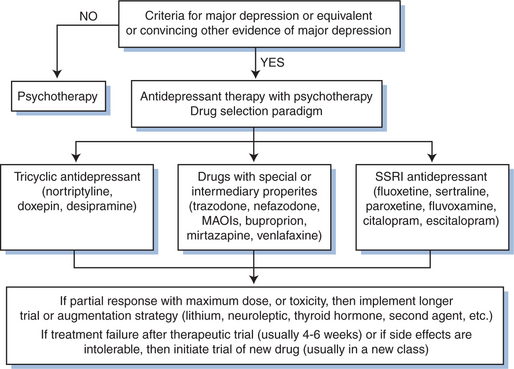

Treatment of Major Depression

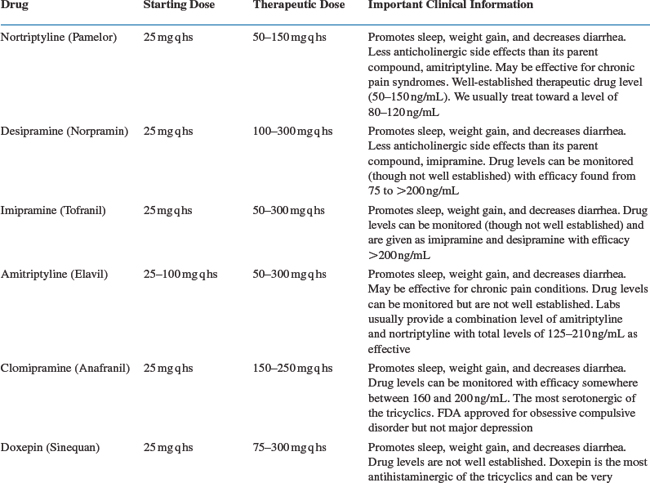

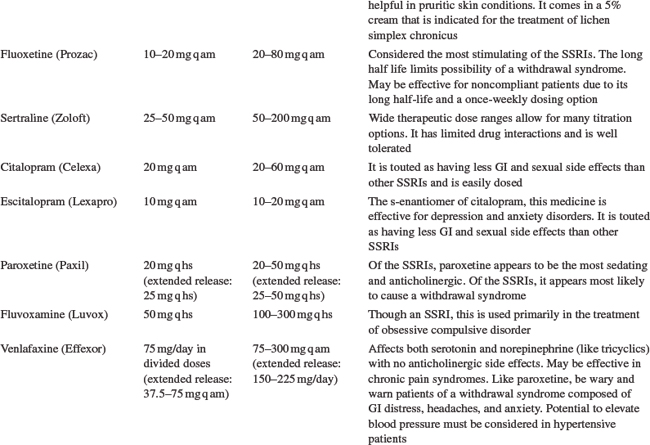

Antidepressant drugs are targeted to treat the underlying chemical imbalance in the brain that is associated with major depression (see Fig. 63-1). Patients with HIV/AIDS are prescribed antidepressants more often than any other class of psychotropics.41 Antidepressants include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), and other atypical drugs (bupropion, venlafaxine, duloxetine, mirtazipine, and trazodone). The development of SSRIs brought to market a class of antidepressants that were relatively easy to use, had limited side effects, and were safer in overdose. Though not more effective than tricyclics or MAOIs, the newer antidepressants offered primary care (and specialist) physicians the opportunity to treat the depressions seen so often in their clinics. To date, studies have shown no antidepressant more effective than others in treating depression among HIV-positive patients as a group. For that reason, much of the discussion here is generally related to the treatment of depression in all patients. In general, side effect profiles can guide the selection of an antidepressant agent because of their similar efficacies as a whole. For example, the side effects of TCAs can be capitalized on to treat an HIV-positive patient who is underweight, has diarrhea, and sleeping problems. Table 63-142 provides a list of antidepressants, dose ranges, and clinically important side effects and benefits (aside from antidepressant effects).

General Considerations

Successful antidepressant treatment requires consistent patient adherence and titration to an adequate therapeutic dose. We cannot overemphasize the importance of close follow-up with patients suffering from depression. It is not appropriate to diagnose a depression (with its inherent risk of suicide), start a medication (that may be initially agitating and cause other side effects prior to any benefit) and have the patient follow-up in 3 to 4 weeks. Close follow-up (initially weekly) gives the opportunity to provide support, stability, and close observation of any side effects that might warrant action. In order to minimize side effects, clinicians should start therapy at low doses and slowly increase to full doses or therapeutic serum levels (available for some of the tricyclic antidepressants). If a patient experiences any intolerable side effects, he may have already stopped the medicine (this is important to ask). If changing medications due to side effects, drugs in the same class still have the potential to offer improved response and decreased adverse reactions.43 At the same time, patients experiencing relief of depressive symptoms and annoying but tolerable side effects such as insomnia, constipation, or sexual dysfunction should be encouraged and receive adjunctive treatments (e.g., trazodone for insomnia or increased water and fiber intake for constipation). A full trial of an antidepressant is 6 to 8 weeks at a standard therapeutic dose.44–46 After this time, patients experiencing minimal or partial relief of symptoms should be considered for higher doses, a different medicine, or an augmenting agent. Lithium addition is the augmenting strategy best supported by evidence. Other promising augmenting agents include triiodothyronine, pindolol, and DHEA.47

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors

As a group, SSRIs have broad clinical indications, including major depression (fluoxetine, sertraline, paroxetine, citalopram, escitalopram), bulimia (fluoxetine), panic disorder (fluoxetine, sertraline, paroxetine), obsessive compulsive disorder (fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, sertraline, paroxetine), generalized anxiety disorder (paroxetine, escitalopram), post-traumatic stress disorder (sertraline, paroxetine), social phobia (sertraline, paroxetine), and premenstrual dysphoric disorder (fluoxetine, sertraline, paroxetine). Common side effects include anxiety, restlessness (akathisia), nausea, diarrhea (increased gastric motility), insomnia, and sexual dysfunction (including decreased arousal or erections, delayed ejaculation, and anorgasmia). Randomized clinical trials have noted fluoxetine most effective of the SSRIs in treating major depression in HIV-positive patients. However, paroxetine, sertraline, and citalopram have also demonstrated clinical efficacy.48

A small number of studies have examined the combination of SSRIs and antiretrovirals for drug interactions. Fluoxetine has been shown to increase concentrations of ritonavir with co-administration.49 At the same time, researchers examining a series of five cases of serotonin syndrome concluded that co-administered ritonavir increased levels of fluoxetine through inhibition of CYP 2D6.50 Although no evidence exists addressing interactions between other SSRIs and antiretrovirals, adverse reactions are possible with all combinations through the potential for CYP450 inhibition, necessitating careful observation of all HIV-positive patients taking SSRIs.51,52 However, SSRIs differ in their pharmacokinetics and potential inhibitory effect on CYP450, possibly making certain drugs, such as citalopram and escitalopram, better choices in patients taking numerous medications.53

Tricyclic Antidepressants

Clinicians most commonly employ TCAs for the treatment of depression (amitriptyline, imipramine, desipramine, doxepin, nortriptyline, protriptyline, trimipramine) and obsessive compulsive disorder (clomipramine). The TCAs last introduced to the market before SSRIs are probably the best tolerated and easiest to use. There is a tendency to underdose TCAs and therefore blood levels are particularly useful in these agents to avoid toxicity and to make sure patients are adequately treated. Unlike most other antidepressants, the serum levels of TCAs are useful and predict response. The TCAs we use most frequently are doxepin, nortriptyline, and desipramine, listed here from most to least sedating. TCAs likely act through reuptake inhibition of norepinephrine and serotonin, though their mechanisms are not entirely clear. Side effects are anticholinergic (decreased gastric motility, dry mouth, urinary retention, and blurry vision), antihistaminergic (sedation and weight gain), and antiadrenergic (hypotension and orthostasis). Cardiac conduction abnormalities (prolonged QT interval) may cause death in overdose and warrant an EKG prior to starting these medicines. Studies show TCAs to be as effective as other antidepressants in HIV-positive patients.54,55 Although no published reports have demonstrated interactions between TCAs and antiretrovirals, the potential for adverse reactions requires close observation of patients receiving both medication types. In one case report, fluconazole, an antifungal agent commonly prescribed to HIV-positive patients, caused increased serum concentrations of nortriptyline.56

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree