ADRENAL LESIONS WITH ENDOCRINE FUNCTION

The cardinal rule of endocrine radiology may be expressed in the phrase diagnosis first, localization second. When dealing with a patient with a suspected endocrine abnormality, the clinician must establish the diagnosis first, using endocrinologic methods. Only after the diagnosis is determined should radiologic methods be used in an attempt to locate an anatomic abnormality. Failure to heed this rule often results in a costly series of tests that produce only false-positive findings.

PHEOCHROMOCYTOMA

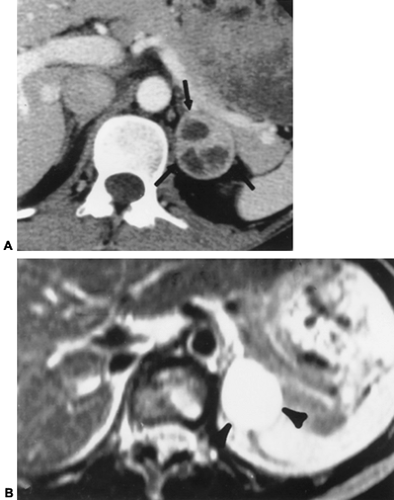

Adrenal pheochromocytomas are almost always >2 cm in diameter and are readily identified by CT. Central necrosis and calcification may occur (Fig. 88-5).2 Pheochromocytomas demonstrate very high signal intensities on T2-dependent spin-echo MRI images and are readily visible.5 In a series of 282 patients with known pheochromocytomas, MRI had a sensitivity of 98%, CT had a sensitivity of 89%, and scanning with 131I-metaiodoben-zylguanidine (MIBG) had a sensitivity of 81%.19 For this reason, MRI is the procedure of choice for the initial localization of pheochromocytomas.

Patients with elevated catecholamine levels and a unilateral adrenal mass on CT or MRI require no further localization studies. Bilateral tumors or adrenal medullary hyperplasia are common in multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome (MEN) type 2A (Sipple syndrome) and type 2B.

When pheochromocytoma is suspected, MRI of the adrenal glands should be performed first, because 90% of these tumors are intraadrenal. If the adrenal glands are normal, MRI or CT of the entire abdomen and pelvis is appropriate, because 98% of all pheochromocytomas and 85% of all extraadrenal pheochromocytomas occur below the diaphragm.20 Extraadrenal pheochromocytomas may occur in paravertebral locations, in the organ of Zuckerkandl, and anywhere from the base of the skull (e.g., glomus jugulare tumors) to the neck of the urinary bladder.

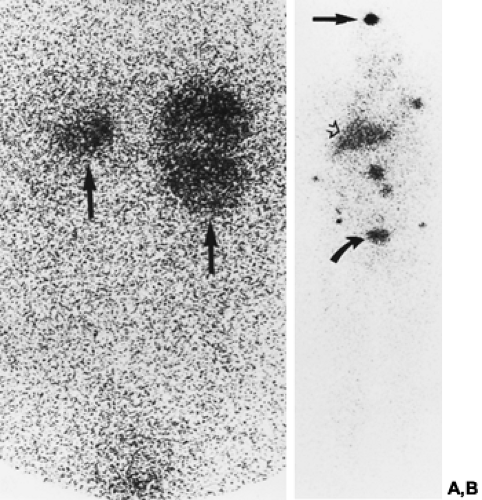

MIBG imaging has proven useful for the detection of ectopic pheochromocytomas. MIBG has a molecular structure that resembles norepinephrine. It is actively concentrated in chromaffin tissue and the adrenergic nervous system. Although MIBG imaging is less sensitive overall than MRI or CT, it is more specific than either.21 For extraadrenal lesions, MIBG scanning has a sensitivity of 67% to 100%, and a specificity of 96%.20 It is particularly helpful for the detection of metastases in patients with malignant pheochromocytomas (Fig. 88-6). MIBG scans alone may not provide sufficient anatomic detail to guide the surgeon, but they help to direct CT and MRI studies toward the ectopically located lesion.

In the rare patient in whom CT, MRI, and MIBG studies yield negative or equivocal results, arteriography or venous sampling may sometimes be helpful.22 These procedures are safe in patients receiving adequate doses of blocking agents, such as phenoxybenzamine. Nonionic contrast agents do not appear to affect circulating catecholamine levels.23

HYPERALDOSTERONISM

Hyperaldosteronism (Conn syndrome) may be caused by a discrete, functioning aldosterone-producing adenoma (APA) or by bilateral hyperplasia. The decision between medical and surgical

therapy hinges on the diagnosis of unilateral adrenal involvement (adenoma) or bilateral hyperplasia.24 Because MRI is more expensive than CT and has a lower spatial resolution, CT is the preferred modality for initial evaluation of the adrenal glands in patients with hyperaldosteronism.17

therapy hinges on the diagnosis of unilateral adrenal involvement (adenoma) or bilateral hyperplasia.24 Because MRI is more expensive than CT and has a lower spatial resolution, CT is the preferred modality for initial evaluation of the adrenal glands in patients with hyperaldosteronism.17

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree