Toxicity

HR

Endometrial cancer

3.28

Pulmonary embolism

2.15

Deep venous thrombosis

1.44

Bone fractures

0.68

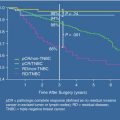

In the most recent Oxford Overview Analysis, there was a nonsignificant increase in stroke deaths (3 extra per 1,000 during the first 15 years) balanced by a nonsignificant reduction in cardiac deaths (3 fewer per 1,000 during the first 15 years), with a resulting minimal net effect of tamoxifen on overall cardiovascular mortality. In the recent ATLAS trial evaluating 10 years of tamoxifen therapy, the benefits of longer durations of tamoxifen outweighed the side effects [8]. After 10 years of treatment with tamoxifen, there was an increased risk for endometrial cancer (relative risk [RR], 1.74) and for pulmonary embolism (RR, 1.87). Endometrial cancers occurred in 3.1 % (with mortality of 0.4 %) in the long-duration group and in 1.6 % (with mortality of 0.2 %) of the 5-year group. There were only 18 pulmonary embolism events and there was an equal amount of mortality (0.2 %) in each treatment group. Additionally, there was no increase in the incidence of stroke and a decrease in the incidence of ischemic heart disease in the long-duration group.

Biomarkers for Tamoxifen Efficacy

Endoxifen, one of two active metabolites that mediate tamoxifen’s therapeutic effect, is formed through the action of the CYP2D6 enzyme [12–14]. Several polymorphisms of the CYP2D6 gene that influence the enzyme’s activity and, therefore, endoxifen levels have been identified. However, studies designed to uncover the link between patient response to tamoxifen and CYP2D6 enzyme activity (or CYP2D6 genotype) have yielded inconsistent results, perhaps as a result of limited sample sizes. Regan and colleagues [15] studied 4,861 postmenopausal patients with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer who were randomized to receive tamoxifen, letrozole, or both. Extracted DNA was used to genotype CYP2D6 and classify each patient as a poor metabolizer (PM), intermediate metabolizer (IM), or extensive metabolizer (EM). No significant association was observed between CYP2D6 phenotype and disease recurrence in tamoxifen-treated patients. Contrary to an existing hypothesis that high rates of tamoxifen-induced hot flashes are a surrogate for EM phenotype, PM and IM phenotype patients experienced the highest rates of hot flashes.

Rae and colleagues studied 1,203 patients with hormone receptor-positive early-stage breast cancer from the ATAC clinical trial who were available for genotyping of CYP2D6 and for whom 10 years of follow-up data were available [16]. Patients were classified as a PM, IM, or EM based on CYP2D6 genotyping. No significant associations were observed between CYP2D6 genotype and recurrence in tamoxifen-treated patients. These two studies confirm that there is no compelling evidence to support CYP2D6 testing in patients who are being considered for tamoxifen therapy and the NCCN treatment guidelines do not support their use [17].

Antidepressants (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI)) are commonly prescribed to breast cancer patients for depression and to reduce the effects of hot flashes, but there is evidence that the concurrent use of certain antidepressants can reduce the efficacy of tamoxifen via the CYP2D6 pathway. Although clinicians should not stop antidepressants prescribed for a psychiatric disorder, better choices among the SSRIs may be considered with concurrent use of tamoxifen and the patient should be aware of the potential interaction [18].

Aromatase Inhibitors

The use of AIs has increased dramatically over the last decade with the introduction of new, more selective aromatase inhibitors, such as anastrozole, exemestane, and letrozole. Current guidelines by ASCO [19] and NCCN [17] recommend third-generation AIs as a component of adjuvant therapy in postmenopausal women, either as monotherapy or in a sequential strategy with tamoxifen. The guidelines do not distinguish between the AIs, even though individual trials used a specific agent. There is no compelling evidence that one agent is superior to another either from an efficacy or tolerability standpoint.

This class of agents effectively blocks the extra-ovarian sites of estradiol synthesis, decreasing its serum concentration by more than 90 % in postmenopausal women [20, 21]. In contrast to tamoxifen, the newer AIs lack partial agonist activity and thus appear to avoid a concerning toxicity associated with tamoxifen, that is the highest risk for developing endometrial cancer [22]. There also appears to be a reduced risk of thromboembolic disease associated with the use of the AIs [22]. Because of this lack of estrogen agonist activity, AIs can potentially result in the loss of bone density (Table 24.2) [22]. Unlike tamoxifen, the AIs do not appear to be beneficial in premenopausal women. Even the newer aromatase inhibitors are unable to inhibit ovarian aromatase activity and, as a result, are unable to suppress estrogen synthesis in premenopausal women.

Table 24.2

Comparison of adverse events: AI and tamoxifen

Adverse event | OR | P value | Abs incidence with AI (%) | Abs incidence with tamoxifen (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Endometrial CA | 0.34 | <0.001 | 0.1 | 0.5 |

Cardiovascular | 1.30 | 1.30 | 4.2 | 3.4 |

Hypercholesterolemia | 2.36 | 2.36 | – | – |

Venous thromboembolism | 0.55 | <0.001 | 1.6 | 2.8 |

Data is available from several randomized clinical trials in the adjuvant setting that show a superior clinical outcome for postmenopausal patients who receive an AI as a component of their adjuvant therapy program. Trial designs compared (1) an aromatase inhibitor to tamoxifen, each for 5 years, (2) a sequence of tamoxifen with an aromatase inhibitor versus either alone as monotherapy for 5 years duration, or (3) 5 years of tamoxifen followed by no additional therapy or 5 years of an AI. Findings from some of the key pivotal trials are summarized below:

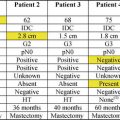

The Arimidex (anastrozole), Tamoxifen Alone, or in Combination (ATAC) study (n = 9,366) compared tamoxifen versus anastrozole versus tamoxifen plus anastrozole [23, 24]. At 120 months, DFS was significantly improved in the anastrozole group versus the tamoxifen group. Among women with hormone receptor-positive tumors, those randomly assigned to receive treatment with anastrozole had a 4.3 % lower absolute rate of breast cancer recurrence after 10 years, and a 2.6 % lower absolute rate of distant metastasis, than those randomly assigned to receive treatment with tamoxifen. The differences between anastrozole and tamoxifen in time to relapse, contralateral breast cancer, and DFS were greatest in the first 2 years of treatment but were maintained throughout the follow-up period, including the period after treatment was completed. This so-called carryover effect is similar to that observed in tamoxifen-treated patients once therapy is discontinued. OS was not significantly different between the groups.

The Breast International Group (BIG) 1-98 trial was a randomized, phase 3, double-blind trial of 8, 010 postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive, early breast cancer that compared 5 years of tamoxifen or letrozole monotherapy or sequential treatment with 2 years of one of these drugs followed by 3 years of the other [25, 26]. At a median follow-up of 8.7 years from randomization, letrozole monotherapy was significantly better than tamoxifen: DFS HR 0.82, OS HR 0.79, distant relapse-free interval (DRFI) HR 0.79, and breast cancer-free interval (BCFI) HR 0.80. At a median follow-up of 8.0 years from randomization for the comparison of the sequential groups with letrozole monotherapy, there were no statistically significant differences in any of the endpoints for either sequence. The 8-year intention-to-treat estimates for letrozole monotherapy, letrozole followed by tamoxifen, and tamoxifen followed by letrozole were 78.6 %, 77.8 %, and 77.3 % for DFS; 87.5 %, 87.7 %, and 85.9 % for OS; 89.9 %, 88.7 %, and 88.1 % for DRFI; and 86.1 %, 85.3 %, and 84.3 % for BCFI [27]. Sequential treatments involving tamoxifen and letrozole do not improve outcome compared with letrozole monotherapy, but it could be considered for an individual patient based on risk of recurrence and treatment tolerability.

The Intergroup Exemestane Study (n = 4,742) compared 2–3 years of tamoxifen followed by exemestane to 2–3 years of tamoxifen followed by further tamoxifen, each to a total of 5 years of therapy [28, 29]. After a median follow-up of 55.7 months, the exemestane arm showed significantly improved DFS (HR, 0.76) but showed no significant benefit for overall survival. Time to contralateral breast cancer, time to relapse, and time to distant relapse were also significantly improved in women who switched to exemestane. Overall survival was significantly improved only in a subgroup analysis that excluded patients with estrogen receptor-negative disease (HR, 0.83).

The Italian Tamoxifen Arimidex (anastrozole) (ITA) trial (n = 426) compared tamoxifen (20 mg daily) for 2 or more years followed by further tamoxifen or anastrozole (1.0 mg daily) to a total of 5 years of adjuvant hormone therapy [30, 31]. At 64 months follow-up, DFS was significantly improved in women who switched to anastrozole (HR, 0.57). There was no significant difference in OS between therapy arms.

The Austrian Breast and Colorectal Cancer Study Group (ABCSG)-8 and German Adjuvant Breast Cancer Group Arimidex/Nolvadex (ARNO)-95 trials had arms identical (n = 3,224) to the ITA trial described above [32]. At 28-months median follow-up, a combined analysis showed significantly improved DFS for women who switched to anastrozole (HR, 0.60). Distant metastases-free survival was also significantly longer with anastrozole (HR, 0.61). There was no significant difference in OS. There were significantly more fractures (p = 0.015) and significantly fewer thromboses (p = 0.034) in patients treated with anastrozole than in those on tamoxifen.

A meta-analysis of the ABCSG-8, ARNO-95, and ITA trials, involving 4,006 patients at a median follow-up of 30 months, found improvements in DFS (HR, 0.59; p < 0.0001), DRFI (HR 0.61, p = 0.002), and OS (HR, 0.71; p = 0.04) for women who switched to anastrozole [33]. In absolute terms, there were significantly fewer recurrences (92 events [4.6 %] versus 159 events [8.0 %]) and significantly fewer deaths (66 [3.3 %] versus 90 [4.5 %]) in the group switched to anastrozole versus those remaining on tamoxifen.

The NCI of Canada study, MA.17, was conducted to determine whether letrozole improves outcome after discontinuation of tamoxifen. Postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer (N = 5,187) were randomized to letrozole 2.5 mg or placebo once daily for 5 years [34–36]. At a median follow-up of 30 months, letrozole significantly improved DFS (P < 0.001), the primary end point, compared with placebo (HR for recurrence or contralateral breast cancer 0.58, P < 0.001). Furthermore, letrozole significantly improved DRFI (HR = 0.60; 0.84; P = 0.002) and, in women with node-positive tumors, OS (HR = 0.61; P = 0.04). Clinical benefits, including an OS advantage, were also seen in women who crossed over from placebo to letrozole after unblinding, indicating that tumors remain sensitive to hormone therapy despite a prolonged period since discontinuation of tamoxifen. The efficacy and safety of letrozole therapy beyond 5 years is being assessed in a re-randomization study, following the emergence of new data suggesting that clinical benefit correlates with the duration of letrozole. MA.17 showed that letrozole is extremely well tolerated relative to placebo. Letrozole (or an alternative aromatase inhibitor) could be considered for all women completing tamoxifen; results from the post-unblinding analysis suggest that letrozole treatment could also be considered for all disease-free women for periods up to 5 years following completion of adjuvant tamoxifen [34].

Recent reports have also suggested that obese women with early-stage breast cancer, in particular those with body mass index (BMI) ≥35 kg/m2, may have a greater risk of disease recurrence when treated with anastrozole compared to their ideal weight counterparts or those treated with tamoxifen. These findings raise a concern that aromatase inhibition in obese women may be a less effective risk reduction strategy and/or the use of the less potent aromatase inhibitors can adversely impact on clinical outcome [37]. To date, the clinical evidence suggesting that one third-generation aromatase inhibitor is more effective than another has been sparse, but preclinical data and clinical surrogates of clinical activity have shown that letrozole is more potent than anastrozole at suppressing estradiol and estrone sulfate [38]. Whether the differences in estrogen suppression with anastrozole or letrozole actually translate into a different clinical outcome cannot be determined from these data. The ALIQUOT study (Anastrozole vs. Letrozole, an Investigation of Quality of Life and Tolerability) compared the ability of anastrozole and letrozole to suppress estrogen in obese postmenopausal women with early-stage breast cancer. Letrozole appeared to be more effective; however, this small study did not demonstrate a differential effect on clinical outcome. Furthermore, the association between obesity and breast cancer is certainly more complicated than suggesting estradiol alone is the culprit. Increased levels in insulin, inflammatory mediators, and other proteins have been implicated as risk factors for breast cancer and breast cancer recurrence in obese patients [37].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree