Figure 43.1 Course of acute hepatitis A. HAV = hepatitis A virus; ALT = alanine aminotransferase; anti-HAV = antibody to hepatitis A virus. (Adapted from Martin P, Friedman LS, Dienstag JL. Diagnostic approach to viral hepatitis. In: Thomas HC, Zuckerman AJ, eds. Viral Hepatitis. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1993:393–409.)

The average incubation period of HAV infection is 28 days (range 15 to 50 days), with peak fecal viral shedding and infectivity occurring before the onset of clinical symptoms, which may include anorexia, fever, malaise, fatigue, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and right upper quadrant discomfort. In acute HAV infection, these symptoms tend to occur 1 to 2 weeks before the onset of jaundice. Replication of HAV occurs exclusively within the cytoplasm of the hepatocyte, where the virus causes a noncytopathic infection. Hepatocellular damage is due to the host’s immune response as the infected hepatocytes are cleared and is clinically observed by marked reduction of HAV RNA. Acute liver failure is rare and occurs in about 0.5% of infected individuals, more frequently in adults than in children. The overall case-fatality rate of acute HAV is 0.3% to 0.6% but reaches 1.8% among adults >50 years. Prompt referral of acute liver failure cases to a transplant center should be performed at the earliest. Patients with chronic liver disease who contract HAV are at particular risk of hepatic decompensation, which has led to the recommendation that HAV-naïve patients with chronic liver disease should be vaccinated against HAV. Most infected individuals recover uneventfully although the illness can occasionally be bimodal or relapsing. Chronic infection with HAV does not occur but a protracted cholestatic phase may be present with persistent jaundice and pruritus before the eventual recovery.

Extrahepatic manifestations of HAV include acute pancreatitis, acalculous cholecystitis, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, aplastic anemia, reactive arthritis, effusions, mononeuritis multiplex, and Guillain–Barré syndrome. HAV-related acute kidney injury has been reported in cases from Asia, possibly mediated by immune complexes or interstitial nephritis.

Routine diagnosis of acute HAV infection is made by detection of IgM anti-HAV antibody in serum (Table 43.1), which becomes detectable 5 to 10 days before the onset of symptoms and persists for 3 to 12 months after infection. IgG anti-HAV antibody develops early in infection and persists indefinitely. The presence of IgG anti-HAV in the absence of IgM anti-HAV reflects immunity either from prior infection or from vaccination.

| Type | Diagnostic tests | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Hepatitis A virus (HAV) | IgM anti-HAV IgG anti-HAV | Acute infection Resolved infection, immunity |

| Hepatitis B virus (HBV) | HBsAg IgM anti-HBc HBeAg, HBV DNA Anti-HBs IgG anti-HBc | Indicates infection Acute infection Indicates replication Indicates immunity Current or prior infection |

| Hepatitis C virus (HCV) | Anti-HCV HCV RNA | Indicates infection Indicates infection/viremia |

| Hepatits D virus (HDV) | IgM anti-HDV Anti-HDV | IgM anti-HBc positive indicates coinfection IgG anti-HBc positive indicates superinfection Indicates infection |

| HDV RNA and HDV antigen | Research tools at present | |

| Hepatitis E virus (HEV) | IgM anti-HEV IgG anti-HEV | Acute infection Resolved infection |

| EBV | EBV IgM and PCR | Indicates infection |

| CMV | CMV IgM and PCR | Indicates infection |

Abbreviations: EBV = Epstein–Barr virus; CMV = cytomegalovirus.

Therapy

Acute HAV infection is self-limited without chronic sequelae. About 85% of acute HAV cases have clinical and biochemical recovery within 3 months and nearly all have complete recovery by 6 months from the time of infection. Treatment is largely supportive and includes adequate nutrition, hydration, avoidance of hepatotoxic medications, steroids, and abstinence from alcohol (Table 43.2). Because acute HAV is more likely to lead to hepatocellular failure in adults, especially in those with underlying chronic liver disease, these patients require close follow-up until symptoms resolve.

| Type | Major focus | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Hepatitis A | Symptomatic therapy | Recognition of ALF and promptly refer to transplant center |

| Hepatitis B | Symptomatic therapy. Oral agents for acute severe HBV | Observe for ALF |

| Hepatitis C | Pegylated interferon +/− ribavirin | Treatment efficacious in acute HCV |

| Hepatitis D | Consider anti-HBV agents in severe cases Prevention: HBV vaccine | Clinically more severe than HBV alone |

| Hepatitis E | Ribavirin monotherapy is effective | FHF common in pregnant women. Transmission can be enteric or zoonotic. Can become chronic in immunocompromised |

| EBV | Symptomatic therapy | Risk factor for PTLD |

| CMV | Immunocompetent: monitor Immunocompromised: ganciclovir, forscarnet, or cidofovir |

Abbreviations: EBV = Epstein–Barr virus; CMV = cytomegalovirus; FHF = fulminant hepatic failure; PTLD = post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disease.

Universal precautions to prevent transmission among close contacts, good personal hygienes and immunization are recommended. Passive prophylaxis with intramuscular polyclonal immunoglobulin before and after exposure is safe and efficacious. Pre-exposure prophylaxis with immunoglobulin should be reserved for nonimmune patients at risk for HAV who are allergic to HAV vaccine. Postexposure prophylaxis with immune globulin is recommended for the following high-risk groups in whom protective antibody titers should be generated quickly: (1) close household and sexual contacts of an index patient with documented acute HAV, (2) staff and patients of institutions for the developmentally disabled with outbreaks of HAV, (3) children and staff of day-care centers with an index case of HAV, (4) those exposed to protracted community outbreaks, and (5) travelers and military personnel who plan to visit countries endemic for HAV. Active immunization with an inactivated HAV vaccine has been available in the United States since 1995. Recent literature suggests that the efficacy and effectiveness of HAV vaccine is superior to passive immunization even for postexposure prophylaxis.

Hepatitis B virus

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is the most common cause of chronic viral hepatitis worldwide and is also a major cause of acute viral hepatitis, especially in developing nations. There are an estimated 400 million people chronically infected with HBV worldwide. In the Far East and sub-Saharan Africa, up to 20% of the population has serologic evidence of current or prior HBV infection. In the United States, although HBV infection is less frequent, the prevalence of chronic HBV is much higher in certain immigrant communities, including Asian Americans. After acute HBV infection, the risk of chronic infection varies inversely with age. Thus, children younger than the age of 5 have a high risk of chronicity after acute HBV infection, whereas an immunocompetent adult has ≤5% likelihood.

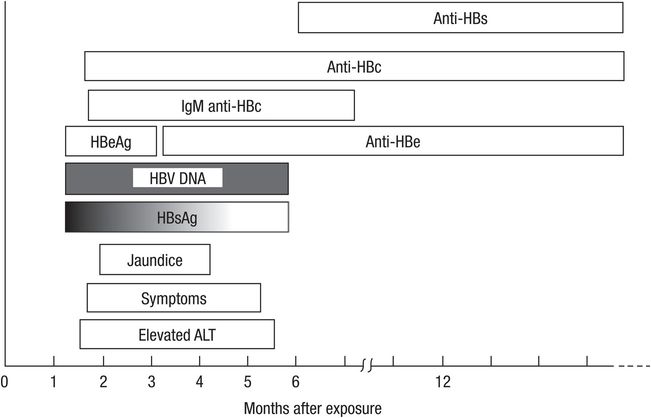

HBV is a DNA virus transmitted predominantly by a parenteral route or intimate contact with an infected subject. In Asia and other hyperendemic areas, vertical transmission is an important transmission route, whereas sexual and percutaneous transmission predominates in the Western world. The incubation period is 45 to 160 days. The typical course of a patient with acute HBV infection is illustrated in Figure 43.2. Typically, elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels and clinical symptoms appear earlier than jaundice. However, not all patients with acute HBV infection develop jaundice. About 70% of patients with acute HBV infection develop subclinical or anicteric hepatitis and only 30% develop icteric hepatitis. Paradoxically, the patient with anicteric and clinically less severe acute HBV infection is more likely to become chronically infected than the individual with more symptomatic acute infection because a brisk immune response causes more hepatic dysfunction but also a greater likelihood of ultimate clearance of HBV infection. The symptomatic patient should be reassured that full recovery is likely but should be warned to report back if symptoms such as deepening jaundice, severe nausea, or somnolence develop because these symptoms may herald acute hepatic failure. Acute liver failure occurs in approximately 0.1% to 0.5% of acute HBV cases. Like acute HAV, acute infection may be more severe in patients with underlying chronic liver disease.

Figure 43.2 Typical course of acute hepatitis B. HBsAg = hepatitis B surface antigen; ALT = alanine aminotransferase; HBV DNA = hepatitis B virus DNA; HBeAg = hepatitis B e antigen; Anti-HBc = antibody to hepatitis B core antigen; Anti-HBe = antibody to hepatitis B e antigen; Anti-HBs = antibody to hepatitis B surface antigen. (Adapted from Martin P, Friedman LS, Dienstag JL. Diagnostic approach to viral hepatitis. In: Thomas HC, Zuckerman AJ, eds. Viral Hepatitis. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1993:393–409.)

The diagnosis of acute HBV hepatitis is made by detection of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and IgM anti-hepatitis B core antibody (anti-HBc IgM) in the serum (Table 43.3). Resolution of HBV infection is characterized by loss of HBsAg. Development of the corresponding neutralizing antibody to HBsAg, anti-HBs, indicates resolution of infection. IgM anti-HBc declines and becomes undetectable whereas IgG (“total”) anti-hepatitis B core antibody (anti-HBc IgG) persists after resolution of infection. Detection of IgG anti-HBc distinguishes immunity-acquired from prior infection rather than vaccination in a patient with detectable anti-HBs.

| IgM anti-HAV |

| HBsAg (if positive, then IgM anti-HBc, HBV DNA, HBeAg) |

| Anti-HCV antibody (if positive, then HCV RNA) |

| Consider testing for HEV, HSV, CMV and EBV if A, B, and C tests are negative. Testing for other viruses is at clinician’s discretion |

Individuals who are immunocompromised or have another chronic condition such as renal failure are more likely to develop chronic infection. Children younger than 5 years and the

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree