Figure 123.1. Submandibular actinomycotic infection “lumpy jaw.” (Courtesy of Dr. Arthur Di Salvo.)

Thoracic disease

The usual presentation is an indolent, progressive course that involves the pulmonary parenchyma and/or the pleural space. Chest pain, fever, and weight loss are common. A cough, when present, is variably productive. The most common radiographic appearance is either a mass lesion or pneumonia. Cavitary disease or hilar adenopathy may develop. Many cases have pleural thickening, effusion, or empyema. Pulmonary disease that crosses fissures or pleura; involves the mediastinum, contiguous bone, or the chest wall; or is associated with a sinus tract should suggest actinomycosis. Mediastinal infection is uncommon. The structures within the mediastinum and the heart, including heart valves, can be involved in various combinations, resulting in a variety of presentations. Isolated disease of the breast occurs rarely.

Abdominal disease

Abdominal actinomycosis is often unrecognized. Months to years usually pass from the inciting event (e.g., appendicitis, diverticulitis, peptic ulcer disease, foreign-body perforation, bowel surgery, or ascension from IUCD-associated pelvic disease) to diagnosis. Because of the flow of peritoneal fluid and/or direct extension of primary disease, virtually any abdominal organ, region, or space can be involved. The usual presentation is either an abscess or a mass lesion that is often fixed to underlying tissue and mistaken for a tumor. Sinus tracts to the abdominal wall or perianal region may develop. Hepatic infection usually presents as single or multiple abscesses or masses. Isolated disease is presumably via hematogenous seeding from cryptic foci. All levels of the urogenital tract can be infected. Bladder involvement, usually due to extension of pelvic disease, may result in obstruction or fistulas to bowel, skin, or uterus. Renal disease usually presents as pyelonephritis and/or renal and perinephric abscess.

Pelvic disease

Actinomycotic involvement of the pelvis is strongly associated with IUCDs. Although the magnitude of risk is unclear, it would appear to be small. Disease rarely occurs when an IUCD has been in place for less than 1 year; however, the risk of infection increases with time and is often seen in the setting of the “forgotten” IUCD. Symptoms are typically indolent with fever, weight loss, abdominal pain, and abnormal vaginal bleeding or discharge being most common. An endometritis, if untreated, may progress to a pelvic mass or a tubo-ovarian abscess. Unfortunately, diagnosis is often delayed, and a “frozen pelvis” mimicking malignancy or endometriosis will develop by the time of recognition.

Central nervous system

Central nervous system (CNS) infection is rare. Single or multiple brain abscesses are most common, usually appearing on computed tomography (CT) as a ring enhancing lesion with a thick wall that may be irregular or nodular. Rarely primary meningitis occurs.

Musculoskeletal infection

Osteomyelitis is usually due to adjacent soft-tissue infection but may be associated with trauma (e.g., fracture of the mandible) or hematogenous spread. The uncommon infection of the extremities is usually a result of trauma. Skin, subcutaneous tissue, muscle, and bone are involved alone or in various combinations. Cutaneous sinus tracts frequently develop. Actinomycotic infections of hip and knee prostheses have also been described.

Disseminated disease

Hematogenous spread of infection from any location may rarely result in multiorgan involvement, with the lungs and liver most commonly affected. The presentation of multiple nodules may mimic disseminated malignancy. A. meyeri appears to have the greatest capability of causing this syndrome.

Diagnosis

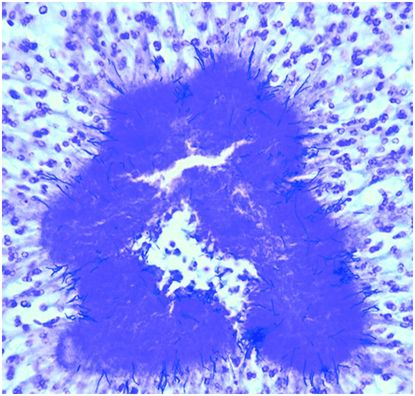

The diagnosis of actinomycosis is rarely considered. Most often the first mention of actinomycosis is from the pathologist after extensive surgery (Figure 123.2). Because medical therapy alone is often sufficient for cure, the challenge for the clinician is to consider actinomycosis so that this uncommon and unusual infection can be diagnosed in the least invasive fashion and unnecessary surgery can be avoided. CT- or ultrasound-guided aspirations or biopsies are successfully used to obtain clinical material for diagnosis, although surgery may be required. The diagnosis is most commonly made by microscopic identification of sulfur granules (an in vivo matrix of bacteria and host material) in pus or tissues, although occasionally sulfur granules can be grossly identified from draining sinus tracts or pus. Microbiologic identification is less frequent, due to either prior antimicrobial therapy or omission. To optimize yield, the avoidance of even a single dose of antibiotics is mandatory. Because these organisms are normal oral and genital tract flora, their identification in the absence of sulfur granules from sputum, bronchial washings, and cervicovaginal secretions is of little significance. Although not routinely utilized, 16S rRNA gene amplification and sequencing has been successfully used to increase diagnostic sensitivity.

Figure 123.2. Actinomycotic sulfur granule demonstrating the slender, branched gram-positive filaments of A. israelii; magnification, ×100. (Courtesy of Dr. A. T. Warfield, Department of Cellular Pathology, University Hospital Birmingham NHS FT, Birmingham, UK.)

Treatment

Antimicrobial therapy

Controlled trials either evaluating antimicrobials or designed to define duration of therapy in the treatment of actinomycosis have not been performed and will never be done. Therefore, treatment decisions are based primarily on the collective clinical experience. Two principles of therapy have evolved. It is necessary to treat this disease both with high doses and for a prolonged period of time. Presumably, this is because of the difficulties of antimicrobials penetrating the thick-walled masses that commonly occur with this infection and/or the sulfur granules themselves.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree