Classification

The most common variant of generalized GM1-gangliosidosis, type I, presents in early infancy and progresses rapidly to death, usually by 2–3 years of age [1]. Death in the first few months of life from severe cardiomyopathy occurs in some cases, before the development of severe neurodegenerative manifestations of the disease. Severe GM1-gangliosidosis may present as non-immune foetal hydrops.

Generalized GM1-gangliosidosis, type II, is characterized by the onset between 6 and 36 months of age of developmental arrest, then regression with seizures and spasticity, in the absence of the prominent hepatosplenomegaly, skeletal abnormalities or macular cherry-red spots seen in infants with type I disease. The course of the disease is more protracted, generally culminating in death late in the first decade of life.

Type III disease is a late-onset variant presenting as generalized dystonia with dysarthria and ataxia. Parkinsonism and other signs of extrapyramidal involvement are common. Cognitive impairment develops later in the course of the disease. Survival is generally measured in decades after the initial onset of symptoms.

Galactosialidosis is a very rare disorder of ganglioside metabolism caused by deficiency of protective protein (cathepsin A) resulting in combined deficiency of lysosomal β-galactosidase and α-neuraminidase [2, 3]. This disease is covered more completely in Chapter 15.

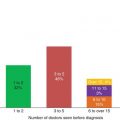

Figure 8.1 Storage histiocytes in bone marrow. Panel (a): Light microscopic appearance, Wright stain. Panel (b): Electron microscopic appearance of lamellar membranous inclusions.

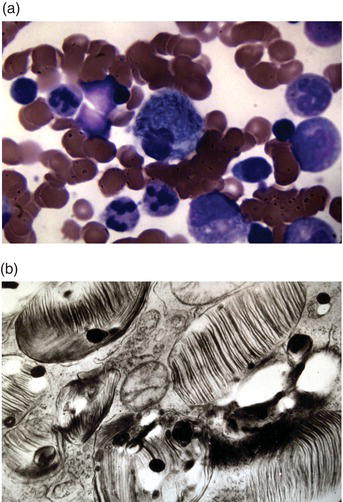

Figure 8.2 Thin-layer chromatogram of urinary oligosaccharides. The atternof oligosaccharides characteristic of various lysosomal storage diseases is revealed by staining the oligosaccharides separated by TLC with orcinol/sulfuric acid.

Epidemiology

The global incidence of GM1-gangliosidosis is estimated to be 1 in 300,000 to 100,000 births; however, the incidence is much higher in some genetic isolates, such as in the Canary Islands, southern Brazil, and among Roma gypsies.

Classification

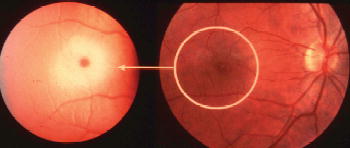

By far the most common variant of GM2-gangliosidosis is late-infantile Tay–Sachs disease, caused by HEXA mutations. The disease generally presents towards the middle of the first year of life with developmental arrest, loss of visual fixation, abnormalities of tone, macrocephaly, and an exaggerated startle reflex (“hyperacusis”). It pursues a stereotypic clinical course, with rapid neurological deterioration, the appearance of classical cherry-red spots of the macula (Figure 8.3), blindness and seizures, culminating in death at 3–4 years of age.

Late-infantile Sandhoff disease is clinically almost indistinguishable from Tay–Sachs disease. However, mild enlargement of the liver and radiographic evidence of skeletal involvement may be found. The clinical course is the same as for Tay–Sachs disease.

The juvenile variants of Tay–Sachs disease and Sandhoff disease are indistiguishable [4]. The onset is often heralded by the development of dysarthria and incoordination progressing to frank ataxia. Cognitive impairment is highly variable; some patients presenting in later childhood show very little or no intellectual impairment until late in the course of the disease. Acute psychoses are very common in patients with the juvenile variants of the diseases. The psychoses are characteristically resistant to treatment with conventional antipsychotic medications.

Figure 8.3 Macular cherry-red spot. The accumulation of ganglioside in ganglion cells creates a ring of pallor resulting in abnormal prominence of the centre of the macula which is devoid of ganglion cell bodies in the normal retina.

Adult-onset Tay–Sachs disease is much more common than adult-onset Sandhoff disease, but the onset, clinical course and outcome are the same. It is more common in Ashkenazi Jews than among other populations because of the frequency of heterozygosity for severe HEXA mutations in that population. Adult-onset Tay–Sachs disease is often the result of compound heterozygosity for one of the two common severe HEXA mutations (1278insTATC; IVS12 + 1 G > C), along with a mild mutation, such as G269S. This variant may present at any age as an atypical cerebellar ataxia, atypical motor neurone disease or psychosis. Cognitive impairment only occurs late in the course of the disease.

Tay–Sachs disease caused by deficiency of the GM2 activator protein (GM2A mutations) is clinically indistinguishable from classical variants of Tay–Sachs disease. Diagnosis is complicated owing to the fact that measurements of β-hexosaminidase activity using synthetic substrates are invariably normal.

Epidemiology

The overall incidence of GM2-gangliosidosis is of the same order as GM1-gangliosidosis. However, approximately 1 in 25–30 Ashkenazi Jews is a carrier of the disease, and prior to the introduction of screening for carriers of the disease, Tay–Sachs disease (late-infantile GM2-gangliosidosis, TSD variant) was 100 times more common in Ashkenazi Jews than in other populations. Large-scale screening programmes to identify carriers and provide genetic counselling, including prenatal diagnosis, have led to a marked decrease in the incidence of the disease [5]. Sandhoff disease (late-infantile GM2-gangliosidosis, Sandhoff variant) is very rare, except in some relatively isolated, inbred communities. Although carrier detection of Tay–Sachs disease also identifies carriers of Sandhoff disease, carrier detection programmes have not had a significant impact on the frequency of the disease because of the focus on Ashkenazi Jews and the fact that the disease is very rare and the frequency of the condition is not increased in that population.

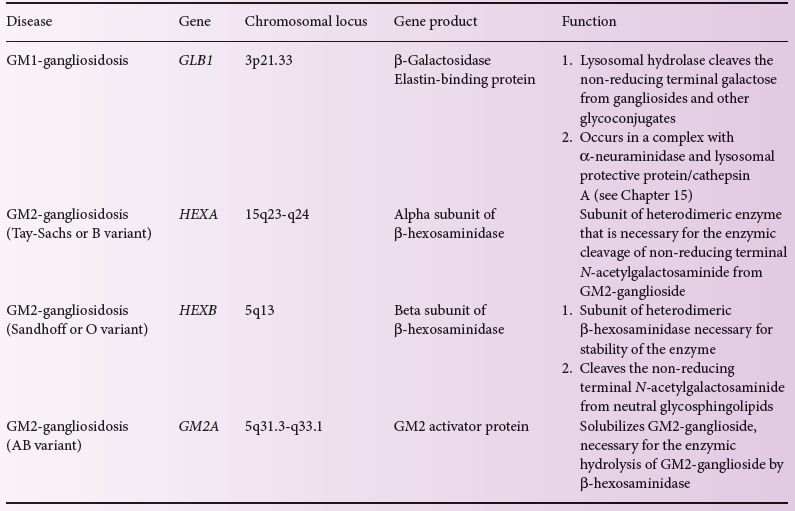

Table 8.1 Genetics of the gangliosidoses.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree