5 T1b Glottic Cancer

Abstract

Early-stage squamous cell carcinomas of the glottic larynx can be treated with either larynx-preserving surgery or definitive radiotherapy with high rates of cure and excellent voice preservation. T1b cancers involving both vocal folds represent a unique cohort deserving of special anatomic and staging considerations. In this chapter, we discuss strategies for patient selection, with particular attention to the significance of anterior commissure involvement and depth of invasion. Practical guidelines for radiation simulation, field design, and dose fractionation are reviewed, along with common clinical pitfalls. Investigational strategies, including intensity-modulated radiotherapy, are also explored.

5.1 Introduction

Patients with Tis-T2 cancer of the glottis can be treated with larynx-preserving strategies such as radiotherapy, transoral laser microsurgery (TLM), or open partial laryngectomy. Within this group, patients with T1b disease represent a unique subset requiring special consideration and careful attention to the anatomic extent of disease, resectability, and voice quality.

5.2 Evaluation

A complete history, including current or former tobacco use, changes in voice quality, and history of rigorous voice use, is important for discussion of treatment options.

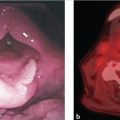

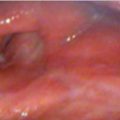

Careful evaluation of the larynx using indirect laryngoscopy, video stroboscopy, and direct laryngoscopy is essential for pretreatment staging and decision-making. Evaluation should include an assessment of anterior commissure (AC) involvement, extent and location of mucosal disease, supra- or infraglottic extension, and impairment of vocal fold mobility. On direct laryngoscopy and biopsy, the depth of invasion may have prognostic implications for voice quality following TLM.

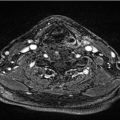

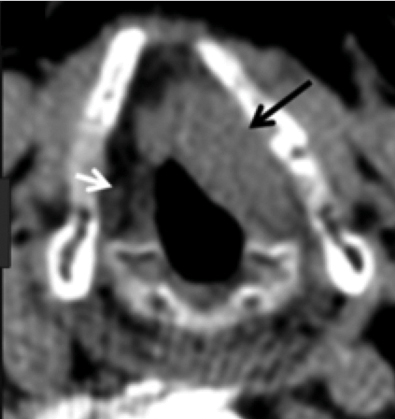

For patients with a bulky cancer or cancer involving the AC, thin-cut CT of the neck or MRI may be useful for identifying early cartilage invasion or paraglottic extension that is not appreciated on clinical examination alone ( Fig. 5‑1). Imaging may also be useful in cases with submucosal cancer, where clinical examination can underestimate the true extent of the cancer.

5.3 Selection of Treatment Modality

TLM and hemilaryngectomy are the primary alternatives to radiotherapy. TLM is minimally invasive and can achieve high rates of local control, although repeated applications are sometimes required. There are no randomized trials powered to assess the differences in oncologic outcomes between TLM and radiotherapy. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 Depending on the extent of disease and treatment modality, excellent oncologic and voice outcomes can be achieved with both radiotherapy and TLM. 6 , 7 , 8 Compared with radiotherapy and TLM, hemilaryngectomy is associated with increased morbidity and is therefore reserved for bulky disease or as salvage. 9 The selection of a definitive treatment modality is highly dependent upon the availability of technical expertise and referral patterns.

In practice, superficial lesions and lesions involving the posterior portions of the cord are often amenable to TLM with very limited morbidity. Lesions that are more deeply invasive, requiring European Laryngological Society (ELS) type III to VI resections, may be associated with poorer voice outcomes, and these cases are often referred for radiotherapy. Similarly, some authors routinely refer patients with AC involvement for radiotherapy due to concerns regarding operative exposure, difficulty achieving clear margins, and the potential for impaired vocal outcomes with extensive anterior commissure involvement. 10 , 11 , 12 Finally, many patients are referred for refractory disease despite multiple surgical attempts.

5.3.1 Anterior Commissure Involvement

Historically, AC involvement has been a negative prognostic factor for patients treated with either radiotherapy or TLM. 13

Tumors involving the AC can be difficult to expose completely for resection, and it can be difficult to achieve negative margins at this location. 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 Hoffmann and colleagues showed that AC was associated with a disease-free survival of 54.6%, compared with 79.8% for cancers without AC involvement, and that a greater number of these patients required other modalities for salvage, including total laryngectomy. 11 Similarly, Rödel and colleagues found that AC involvement was associated with lower rates of local control with surgery (5-year local control 73 vs. 89% for T1a, 68 vs. 86% for T1b). 15 Other authors have reported higher rates of local control, albeit with a smaller number of patients. 12 Following resection, patients may be at risk for development of an anterior laryngeal web, which can negatively influence voice quality.

The prognostic importance of AC involvement on outcomes following radiotherapy is more controversial. Much of the clinical data supporting these findings come from an era predating the routine use of CT or MRI imaging and modern dosimetry, potentially resulting in cancers that were understaged or even missed. Additionally, many treatment series span decades and include patients treated with significant variability and technique and dosimetric precision. In a small series, Nozaki and colleagues 16 found AC involvement was associated with worse 5-year local control (58 vs. 89%) and potentially attributable to underdosage anteriorly. Chen and colleagues showed that the impact of AC involvement could be overcome by using higher doses per fraction. 17 In more contemporary series using accelerated fractionation and 3D dosimetry, the effect of AC involvement appears to be attenuated. Le and colleagues identified a difference of borderline statistical significance (80 vs. 91%) for patients with T1 lesions. 18 Chera and colleagues reported on a series of 585 patients with T1–T2 glottic larynx cancer treated with definitive radiation, including 369 patients with AC involvement. Patients with T1a and T1b disease achieved 10-year local control of 93 and 91%, and AC involvement was not associated with adverse outcomes. 19

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree