Section 4 Acute metabolic complications

Hypoglycaemia

Type 1 diabetes

Iatrogenic hypoglycaemia usually results from a mismatch between:

• supply of glucose for metabolic requirements (e.g. as a result of a missed meal)

• rate of utilization (e.g. an increase due to physical exercise)

• a relative excess of insulin leading to a fall in the circulating glucose concentration.

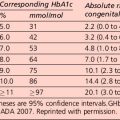

In the Diabetes Control and Complication Trial, the overall risk of severe hypoglycaemia was increased approximately 3-fold in the intensively treated group. This was observed despite strenuous efforts to exclude patients who were thought to be at high risk of hypoglycaemia. The relation between rate of severe hypoglycaemia and mean glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) level was inverse and curvilinear. Factors predisposing to severe hypoglycaemia are presented in Table 4.1. However, in a significant proportion of hypoglycaemic episodes, a clear predisposing factor cannot be identified even with very careful scrutiny of the circumstances.

Table 4.1 Risk factors for severe hypoglycaemia

Other causes of hypoglycaemia in insulin-treated patients are presented in Table 4.2. Their effects in individual patients are variable.

Table 4.2 Causes of recurrent hypoglycaemia in insulin-treated patients

| Changes in insulin pharmacokinetics |

| Altered insulin sensitivity |

| Others |

The symptoms and signs of acute hypoglycaemia may be divided into two main categories:

• Autonomic (adrenergic) – arising from activation of the sympathoadrenal system (Table 4.3). During hypoglycaemia, the body normally releases adrenaline (epinephrine) and related substances. This serves two purposes:

• Neuroglycopenic – resulting from inadequate cerebral glucose delivery (Table 4.3). Specific symptoms vary by age, duration of diabetes, severity of the hypoglycaemia and the speed of the decline. The symptoms in a particular individual may be similar from episode to episode, but are not necessarily so and may be influenced by the speed at which glucose levels are dropping, as well as the previous incidence of hypoglycaemia.

Table 4.3 Autonomic, neuroglycopenic and non-specific symptoms and signs in acute hypoglycaemia

| Autonomic (adrenergic) |

| Neuroglycopenia |

| Non-specific |

Hypoglycaemia and the brain

The most serious consequence of acute hypoglycaemia is cerebral dysfunction with the risk of:

• injury (to self or others). As a result of neuroglycopenia, the patient may become irrational and aggressive. Prompt assistance from another party may then be required to avert loss of consciousness and more serious sequelae.

• Generalized epileptic seizures.

Clinically, hypoglycaemia may be usefully graded as follows:

Hypoglycaemia – counter-regulation

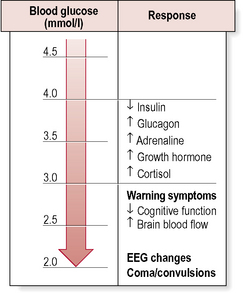

The physiological response to acute hypoglycaemia comprises:

• suppression of endogenous insulin secretion.

• activation of a hierarchy of counter-regulatory responses (Fig. 4.1).

Counter-regulatory hormone responses

Nocturnal hypoglycaemia

Conventional strategies to minimize nocturnal hypoglycaemia include:

• reducing the dose of evening intermediate insulin

• moving the time of the evening injection of intermediate insulin to 2200 hours

• eating a snack containing 10–20 g carbohydrate before bed

Treatment of insulin-induced hypoglycaemia

Grade 3–4 hypoglycaemia

• Buccal glucose gel. Proprietary thick glucose gels (e.g. Glucogel, formerly known as Hypostop) or honey (with variable efficacy) can be smeared on the buccal mucosa.

• Glucagon. Parenteral glucagon (1 mg = 1 unit) can be given by intravenous, subcutaneous or, most reliably and conveniently, intramuscular injection. Glucagon is a hormone that rapidly counters the metabolic effects of insulin in the liver, causing glycogenolysis and release of glucose into the blood. Glucagon can raise the glucose by 3–6 mmol/L within minutes of administration.

Glucagon comes in a glucagon emergency rescue kit, which includes tiny vials containing 1 mg, the standard adult dose. The glucagon in the vial is a lyophilized pellet: it must be reconstituted with 1 ml sterile water, which is included in the ‘kit’. Relatives or friends can learn how to reconstitute and administer glucagon, and this should bolster confidence when dealing with a patient prone to recurrent, severe hypoglycaemia. If glucagon is ineffective within 10–15 min, intravenous dextrose should be administered.

• Intravenous glucose. Administer 25 mL 50% dextrose (or 100 mL 20% dextrose) into a large vein. If a person is unconscious, has had seizures, or has an altered mental status and cannot receive oral glucose gel or tablets, emergency personnel should establish a peripheral or central intravenous line and administer a solution containing dextrose and saline. Dextrose 25% and 50% are heavily necrotic owing to their hyperosmolarity, and should be given only through a patent intravenous line – any infiltration can cause tissue necrosis. Thrombophlebitis is also a well-recognized complication of intravenous delivery.

Recovery from hypoglycaemia may be delayed if:

• the episode of hypoglycaemia has been prolonged or severe

• an alternative/additional cause for impairment of consciousness (e.g. stroke, drug overdose) coexists

• the patient is postictal (seizure caused by hypoglycaemia).

Behavioural problems specific to type 1 diabetes

Idiopathic ‘brittle diabetes’

Considerable difficulties in glycaemic control can occur as a result of a number of problems including delayed gastric emptying (gastroparesis) (see p. 18), drug interactions (e.g. β-blockers, steroids) and problems with insulin absorption.