Section 3 Management of diabetes

Type 1 diabetes – initiating therapy

Insulin regimens

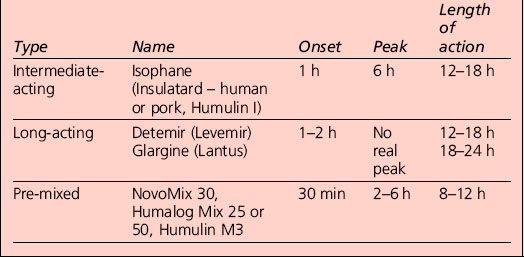

Appropriate combinations of the above insulins can be tailored to the individual; a certain element of this will be trial and error, but close liaison with the health-care provider usually results in the right regime for that person (Table 3.1). The pre-mixed insulins are a popular starting regimen, and the timing of onset, peak and duration of action will depend on the component parts.

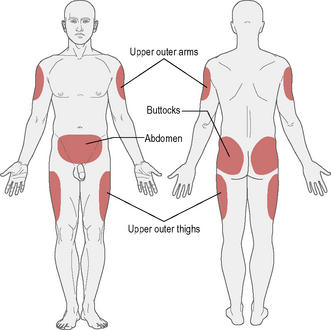

Insulin injection sites

The recommended sites for insulin injection are shown in Figure 3.1. Injection should be given into a pinched-up skin fold using thumb, index and middle finger, taking up the skin and leaving the muscle behind. This will avoid intramuscular injection. Too shallow an injection will be delivered intradermally, and can be painful.

• Insulin absorption is fastest in the abdomen and slowest in the arms and buttocks. Short-acting insulin is best given into the abdomen, and long-acting insulin into the thigh or arm; however, this can be varied according to the most practical site available.

• Most importantly, the injection sites should be ‘rotated’: if the abdomen is the site used most often then rotating around different points regularly is a good idea. This should avoid lipohypertrophy (an accumulation of fat under the skin), which occurs if the same injection site is used repeatedly. If this occurs, it can be unsightly and increases the variability of insulin absorption.

• If a person rotates from limb to limb, it is good idea to try to stick to a schedule whereby the same area is injected at the same time of day, for example morning injection in the abdomen, teatime injection in the leg.

• Insulin absorption may also be accelerated by exercising that part of the body (e.g. injecting legs and then jogging/running).

Different insulin delivery systems

Needle and syringe

This is the traditional method of delivery. The following steps are recommended:

1. Clean the rubber stopper of the bottle with alcohol. If intermediate-acting or long-acting insulin is being used (cloudy insulins), mix by rolling or rotating the bottle.

2. Open the syringe to the number of units that is needed so that there is air to this point in the syringe.

3. Turn the insulin bottle upside down and inject the stopper with the needle.

4. Push the air inside and withdraw the insulin dose required.

5. Give the syringe a few taps with your finger to get the bubbles to the top, and push the bubbles back into the bottle.

6. Pinch up the area of skin to be injected.

7. Insert the needle at a right angle to the skin and push it in; then push down the plunger to administer the insulin.

Jet injection device

• Allergy. Local allergic reactions are uncommon with modern insulin preparations; reactions to diluent or preservatives are sometimes thought to be of relevance; a change of brand may help, but many cases resolve spontaneously. Transient tender nodules developing at the injection site are suggestive; generalized allergic reactions are exceedingly uncommon. Testing kits are available from insulin manufacturers. Major insulin resistance due to high titres of anti-insulin antibodies that cause antigen–antibody complexes is very uncommon; corticosteroids may be useful.

• Lipohypertrophy. Localized areas of lipohypertrophy, although comfortable to inject into, are thought to cause erratic absorption of insulin from the site. The hypertrophy is attributed to the trophic effects of insulin on fat metabolism. Avoidance of the area may lead to regression; liposuction has been used.

• Lipoatrophy. This has become rare since the introduction of highly purified, and more recently human sequence, insulins. It may be improved by the injection of highly purified soluble insulin around the edge of the lesion.

Altering insulin doses

• Alter one insulin dose at a time.

• Alter the appropriate insulin based on knowledge of the pharmacokinetics of the insulin preparations being used. For example, on twice-daily mixtures of short- and medium-acting insulin:

• A relatively small change (2–4 units) is generally safe; larger changes may be indicated in some instances, but care should be taken to avoid inducing hypoglycaemia. Such small alterations are not always appropriate; the magnitude of the increase or decrease should reflect the overall insulin dose. For example, for a patient stabilized on a daily dose of 40 units, a change of 4 units is 10% of the total; for a patient on 100 units, a proportionately similar change would be 10 units. Moreover, when insulin has just been initiated, tiny daily increases in dose may be too cautious. However, experience is required in judging whether larger increases are indicated.

• If recurrent hypoglycaemia occurs at the higher dose, the patient should drop back to the previous dose.

• Remember that increasing the dose of a pre-mixed insulin preparation will increase both the short- and the longer-acting components.

• Be prepared for discrepancies between theory based on insulin pharmacokinetics and the realities of clinical practice.

Unwanted effects of insulin therapy

Severe insulin resistance

The definition is arbitrary. When daily insulin doses (in excess of 200 units) were needed to control glycaemia, it was considered to reflect severe insulin resistance; this is now largely of historical interest. The concept of insulin resistance is discussed in Section 1.

• Severe insulin resistance syndromes. Specific causes of severe insulin resistance, congenital or acquired, are very rare.

• Brittle diabetes. Whether this entity exists is regarded as contentious by some. Apparently high insulin requirements with swings in control are a feature of some patients with idiopathic brittle diabetes.

• Hormonal stress response to intercurrent illness. Transient insulin resistance may arise in the course of intercurrent illnesses (e.g. sepsis); temporary increases in insulin doses, sometimes necessitating a change to intravenous or multiple subcutaneous doses of short-acting insulin, are required. Insulin may be required during the course of such an illness in patients previously well maintained on oral antidiabetic agents; this will usually be undertaken in the hospital setting. With resolution of the acute episode, reintroduction of oral therapy may be possible.

• Anti-insulin antibodies. The role of acquired anti-insulin antibodies, once thought to be an important mechanism of insulin resistance, has faded with modern, less antigenic, insulin preparations.

• Obesity. Clinical insulin resistance is confined largely to patients with type 2 diabetes whose obesity and associated insulin resistance limits attainment of glycaemic targets despite large doses of insulin. However, type 1 patients can become obese and develop insulin resistance – possible ‘double diabetes’.

Insulin regimens

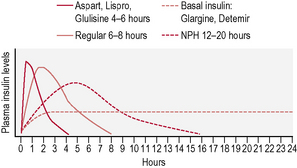

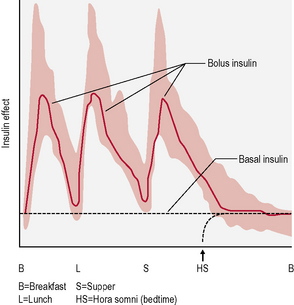

This is the schedule of insulin that a person will decide upon with their health-care professional, and is based on the type of diabetes, physical needs and lifestyle (in particular eating patterns and activity). The variables include type of insulin, timing and dose (Fig. 3.2). There are many regimens, but the most common examples are:

• Insulin added to oral medication. This combination is worthwhile in those with type 2 diabetes where the fasting blood glucose begins to rise despite maximum oral medication. It most often means a dose of long-acting insulin at bedtime.

• Twice-daily insulin. This is either two doses of an intermediate-acting insulin or two doses of a mixed insulin to give more control over postprandial increases in blood glucose (Fig. 3.3). The latter is often used in type 1 diabetes when the individual wants to avoid taking insulin at work/school at lunchtime.

• Basal-bolus insulin. This is essentially intensive insulin therapy and is discussed below (Fig. 3.4).

Adverse effects of insulin therapy

• Hypoglycaemia. This is the most common disadvantage of insulin therapy and occurs when the amount of insulin taken is too much for the amount of food ingested, exercise undertaken or starting level of blood sugar. It may also occur as a consequence of excess alcohol intake (see Section 4).

• Weight gain. When insulin is started, a person will begin to retain fat; this is normal to some extent. People will find they are unable to eat as much as they did previously without putting on weight and therefore they should beware of overeating. Also, eating snacks to avoid hypoglycaemia should be limited as much as possible. It is usually better to reduce the insulin dose rather than eating to justify it.

• Insulin allergy. This is now extremely rare due to the use of human insulin.

Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion therapy

Some important points to know about pumps

• They do not measure blood sugar and so the pump still needs to be directed by blood sugar measurements with a meter and dose adjustments.

• There are two basic rates of delivery: the basal rate, which is a slow, continuous trickle when a person is not eating, and the bolus rate, which is a much higher flow rate delivered when a meal is about to be eaten.

• Much guidance is required, especially at the start, from the diabetes specialist nurse and/or doctor, in addition to a dietitian.

• National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines recommend that pumps be considered in those where other insulin regimes have ‘failed’ – where it is not possible to reduce HbA1c to less than 7.5% without causing ‘disabling hypoglycaemia’. Pumps should also be considered only for patients who are committed to gaining the considerable expertise and competence that the effective use of a pump requires.

Disadvantages of pumps

• Skin infections can occur as the infusion set is left in situ for a few days.

• Ketoacidosis can occur rapidly if the pump disconnects, as short-acting insulin is the only form given.

• Blood glucose must be measured frequently to adjust the pump for best control.

• They are expensive (more than £2500, with annual costs of about £1200).

• Limited availability of pumps supplied from the National Health Service.