27 Strategy for Avoiding Pharyngocutaneous Fistula: Pectoralis Muscle Flap for Salvage Total Laryngectomy

Abstracts

There has been a paradigm shift in the primary management of cancer of the larynx since the results of the Veterans Affairs and Radiation Therapy Oncology Group trials were published. This has led to an increase in the use of organ-preservation protocol (OPP) over laryngeal surgery. Subsequent failure after OPP requires salvage total laryngectomy. The complication rate following salvage total laryngectomy is higher than primary surgery, most probably, due to tissue fibrosis and obliterative endarteritis. The incidence of major and minor complications is reported between 52 and 59%. Pharyngocutaneous fistula (PCF) is the most common component of these complications. These complications increase hospitalization time, cost of treatment, and future incidence of pharyngeal stenosis, significantly impacting the quality of life of patients. There is robust evidence supporting the use of vascularized tissue in the closure of defects following salvage laryngectomy to decrease complications. The vascularized tissue can be a local flap, pedicle flap, or free flap. However, local flap based on sternocleidomastoid or infrahyoid musculature, being located in the radiation field, precludes their use in the salvage setting. These flaps can be used as an overlay or an interpositional flap. Overlay flaps are placed over the primary closure and interpositional flaps are primarily used to augment inadequate pharyngeal mucosa. Using options other than vascularized flaps such as good nutritional support, a salivary bypass tube, timing of starting oral feeds, and avoiding unnecessary neck dissections helps in decreasing the complication rates. In this chapter, we discuss the various strategies for avoiding PCF with a special emphasis on reconstruction using the pectoralis muscle flap in salvage laryngectomy.

27.1 Case Report

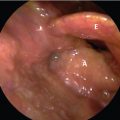

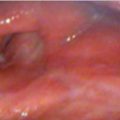

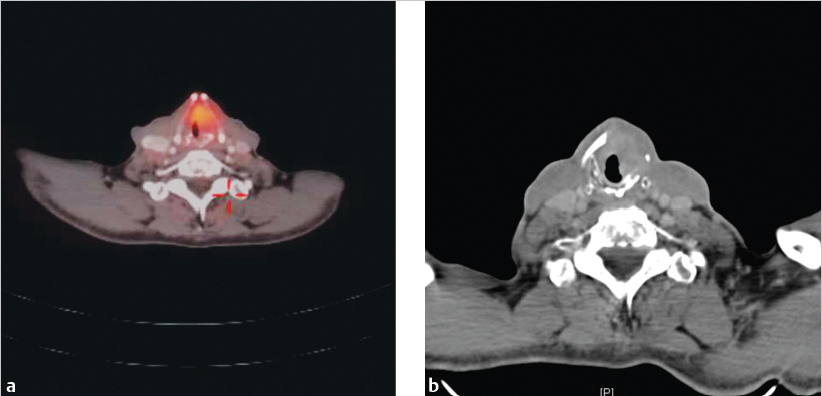

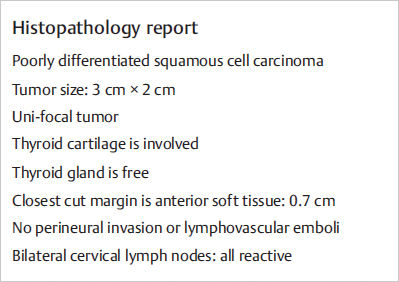

A 63-year-old retired farmer with no comorbidities, and euthyroid, retired farmer, presented with progressive hoarseness for the last 4 months. He had no history of aspiration or difficulty in breathing. He was a beedi smoker, smoking through one pack a day for 20 years as well as drinking socially. At the time of consultation, the patient had good Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) status and presented with a change in voice, having narrow vocal range. No abnormality was detected in the examination of oral cavity and cervical palpation. Examination with a Hopkins rod revealed an ulcero-infiltrative lesion in the entire left true and false vocal cord, which extended to the anterior commissure and reaching the ipsilateral arytenoids without involvement of infraglottis larynx. The mobility of the left vocal fold was restricted. For a better deeper evaluation, a CT scan was performed, which revealed an infiltrative, irregular lesion at the left vocal fold having heterogeneous contrast enhancement. It was seen that the lesion infiltrated the anterior commissure and posteriorly was reaching the ipsilateral arytenoid. There were no signs of extension to the right vocal fold, paraglottic space, and pre-epiglottis space. All the cartilages were intact. Microlaryngoscopy was performed and it was seen that the lesion was involving the anterior commissure, making its complete exposure difficult. Histology was confirmed as squamous cell carcinoma. The patient was diagnosed with cancer of the glottis staged as T2N0. In view of inadequate microlaryngoscopy exposure, the patient was not considered suitable for laser excision and he underwent radical radiation, which consisted of 70 Gy in 35 fractions. However, after a disease- and symptom-free interval of 1.5 year, he presented again with a progressive increase in hoarseness. He did not have any signs of aspiration or difficulty breathing. On Hopkins rod examination, the lesion was seen on the left vocal fold. It had similar extension as seen prior to the radiation. On direct laryngoscopy, the extent of the lesion was confirmed and it was found to have an infraglottic extension ( Fig. 27‑1). The left cord was fixed and the right cord was edematous as a sequel to radiation. Biopsy confirmed recurrent cancer with PET contrast-enhanced CT (CECT) demonstrating fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) avid lesion in the anterior commissure with erosion of the left lamina of the thyroid and exolaryngeal extension ( Fig. 27‑2). In view of its infraglottic extension, any form of conservative laryngeal surgery was not possible. The patient underwent total laryngectomy with primary closure of the remnant mucosa. Essentially, the steps of salvage total laryngectomy are similar to a routine total laryngectomy. However, in this case, an overlay pectoralis myofascial flap was used to cover the mucosal closure ( Fig. 27‑3). The patient had an uneventful satisfactory postoperative period. He was started on liquid diet on the 10th postoperative day. The nasogastric tube was removed on the 12th day after surgery. The final histopathological report is shown in Fig. 27‑4 .

27.2 Discussion

There has been a major shift in the management of laryngeal cancer from surgery to OPP. This paradigm shift occurred following publication of the results of Veterans Affairs (VA) Laryngeal Cancer Study Group 1 and Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) 91–11 2 trials. They demonstrated that OPP had similar survival outcomes as compared to surgery and considering the morbidity associated with total laryngectomy, there was an obvious increase in the use of OPP. Subsequently, with the failure of OPP, there was an understandable rise in the rate of salvage laryngectomy. Stankovic et als. Literatur have shown poor survival with salvage laryngectomy as compared to primary laryngectomy. Apart from recurrence, salvage laryngectomy is also occasionally considered in cases of stage IV chondronecrosis (Chandler’s classification) 4 with patients having debilitating symptoms. The reported major and minor complications associated with salvage laryngectomy ranged from 52 to 59% in view of previously irradiated tissue. 5 In the same study, the incidence of pharyngocutaneous fistula (PCF) was 15% after radiation only and 30% after chemoradiation. In a meta-analysis by Hasan et al, consisting of 50 studies and 3,292 patients, the overall complication rate was 67.5% and PCF was seen in 28.9% cases. 6 These complications lead to prolonged hospitalization, increased treatment costs, and potential need for reoperations. Therefore, it is crucial to discuss various preventive methods that can reduce these complication rates.

There are several predisposing factors to fistula formation such as preexisting comorbidities, pre- and postoperative low hemoglobin and albumin levels, tumor site and stage, concurrent neck dissection, hypothyroidism, etc. As per the VA trial, 1 the rate of salvage laryngectomy was higher in glottic cancer, fixed cords, cartilage erosion, T4, and stage IV cancers. The incidence of salvage laryngectomy in the VA trial was 36%. It was 28, 16, and 31% in patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) followed by radiotherapy (RT), concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT), and only RT, respectively, in RTOG-9111 trial. 2 Salvage laryngectomy was required within 2 years of completion of treatment in 80% of the cases. In a post hoc analysis of the laryngopharyngeal cancers in the TAX 324 trial, there was no significant difference in the incidence of salvage laryngectomy between two-drug (docetaxel and cisplatin [TP]) and three-drug (docetaxel, cisplatin, and fluorouracil [TPF]) groups (20 vs. 11%). 7

27.2.1 Reduction in Leak Rate

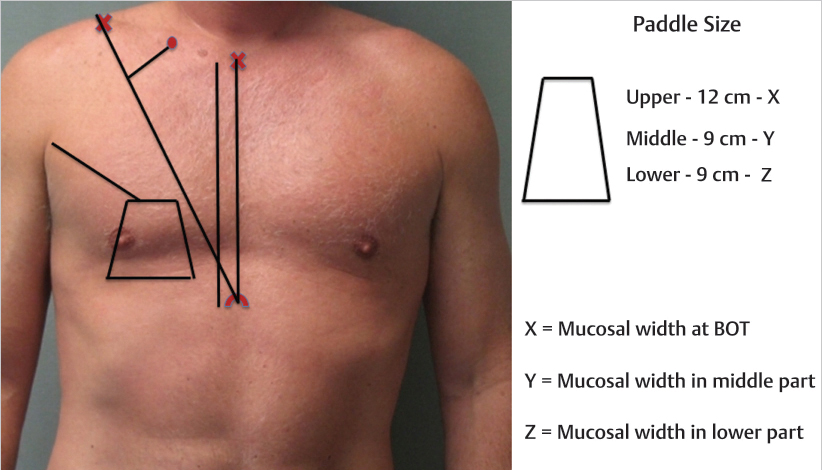

Tissue fibrosis and obliterative endarteritis following radiation are major contributory factors increasing the incidence and severity of complications associated with salvage laryngectomy. 8 Pharyngeal stenosis is a long-term sequel that further impacts swallowing and voice of these patients. The use of a vascularized tissue flap has been studied extensively for reducing the rate of PCF. The flap can be interpositional or overlay. Overlay flap is used when adequate remnant pharyngeal mucosa is available for primary closure. A study by Hui et al in 1996 has shown that 1.5 cm relaxed and 2.5 cm stretch pharyngeal remnant mucosa are adequate for primary closure. 9 The interpositional flap is mainly used to augment inadequate pharyngeal remnant mucosa. However, it is preferred by a few institutes over onlay flap even when adequate pharyngeal remnant mucosa is available. The markings used for an interpositional flap is shown in Fig. 27‑5 .

Paleri et al 10 in a systemic review consisting of 591 patients suggested that there is a definite advantage in using vascularized tissue from outside the radiation field after salvage laryngectomy. Thus, local flaps based on sternocleidomastoid or infrahyoid musculature preclude their use in salvage setting 11 , 12 as they are within the radiation field. Another meta-analysis by Sayles and Grant 13 similarly showed that the rate of PCF after primary closure was 27.6%, which reduced significantly with a flap-reinforced closure (10.3%). A multi- institutional retrospective study 14 consisting of 359 patients from eight institutions also showed that the use of nonirradiated, vascularized flaps reduced the incidence and duration of fistula. The PCF rate was lowest with pectoralis onlay flap (15%) as compared to interposed free flap (25%) or primary closure (35%).

The vascularized flap can be a pectoralis major myofascial flap (PMMF) or a free flap. Comparing them, Chao et al reviewed 36 studies, with 301 patients reconstructed with PMMF and 605 patients with free flaps. Pooled-data analysis revealed that PMMF had higher reported rates of fistula (24.7 vs. 8.9%), requirement for second surgery (11.3 vs. 5.5%), and fewer PMMF patients produced tracheoesophageal speech (17.5 vs. 52.1%). They found no difference in stricture rates or swallowing outcomes. 15 However, the use of free flaps requires surgical expertise, infrastructure, and longer duration of surgery, and also carries a higher risk of flap failure. PMMF has the advantage of a simpler flap harvest and can be performed simultaneously with primary closure of the pharynx, thus reducing overall duration of surgery. Moreover, the bulk of the muscle will cover the great vessels of the neck preventing any major blowout. Coming on to the long-term functional outcomes comparing PMMF and free flap when used for reconstruction specifically after salvage laryngectomy, it was seen that the requirement for esophageal dilatation was higher after PMMF (25 vs. 9%) and 38.7% had a limited oral intake compared to 15.2% of patients who received free flaps. However, the complication rates were similar in both the groups. Subgroup analyses showed a smaller amount of PCFs as well as wound dehiscence in patients where onlay PMMF was used, compared to inset pectoralis myocutaneous flap (pectoralis major myocutaneous [PMMC]). 16 In our case, there was adequate remnant mucosa of more than 3 cm and primary closure was performed along with an overlay PMMF.

Another consideration is the timing of starting oral feeds in the postoperative period. A meta-analysis incorporating four randomized controlled trials and three nonrandomized controlled trials by Hay et al 17 compared patients who had early or late postoperative feeds. This meta-analysis showed there was no difference in complication rate when early feeding was started. However, the population under analysis was heterogeneous, where some studies included postirradiated patients, while others exclude them. Moreover, the method of randomization is not mentioned in three out of four studies. Thus, timing of oral feeds impacting PCF still remains a matter of debate.

It has been postulated that leak rate can decrease further by the use of salivary bypass tube. It helps funnel saliva into the esophagus bypassing the anastomosis; however, a few surgeons believe them to be propagators of fistulas due to constant pressure and irritation along the suture line. It was seen that the rate of PCF was less in patients in whom salivary bypass tube was used (24.6 vs. 8.3%) 18 ; however, it was not significant on multivariate analysis. Bondi et al 19 and Punthakee et al 20 also showed lower fistula rates; however, the sample size was small and multivariate analysis was not done. Thus, the use of a salivary bypass tube to decrease the rate of fistula needs further research.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree