26 Salvage Surgery after Radiotherapy: Total Laryngectomy

Abstract

Radiotherapy for cT1 and cT2 and selected cases of cT3 laryngeal carcinoma is widely used. The recurrence of laryngeal cancer following (chemo)radiotherapy offers ample possibilities for surgical salvage options, if compared to other sites of the head and neck, but various factors must be considered. The diagnosis and staging of laryngeal relapses remains a challenging task. Differentiating between radiation reaction such as edema, fibrosis, and soft-tissue and cartilage necrosis, and recurrent cancer is a difficult clinical and radiological issue. Laryngeal cancer recurs more frequently in the primary site (T) than in cervical lymph nodes (N) or at distance (M). Radiorecurrent cancer is more aggressive due to its high propensity to infiltrate surrounding tissue, are less differentiated lesions, and have typical histological growth pattern with multifocal, lymphovascular and perineural infiltration. For these reasons, in the majority of cases, salvage total laryngectomy (STL) is the only choice in case of persistent/recurrent advanced cancer of the larynx after organ preservation protocols. STL is technically more difficult than primary laryngectomy and is associated with a higher number of complications such as hematoma, edema, suture dehiscence, subcutaneous abscess, and tissue necrosis with consequent pharyngocutaneous fistula (PCF). A second surgical procedure for closing the PCF may be necessary if wound dressing and spontaneous healing are not adequate. Surgical pearls and suggestions have been proposed for preventing PCF; nonetheless, pedicle or free flap harvesting from nonirradiated areas is one of the most commonly used techniques.

26.1 Case Report

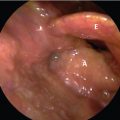

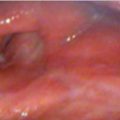

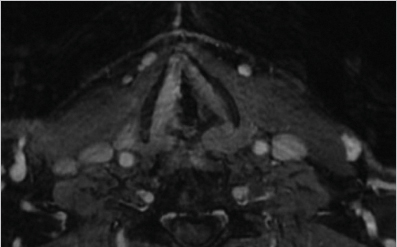

A 66-year-old male ex-cigarette smoker was affected by squamous cell carcinoma of the larynx involving the right vocal cord and the homolateral supraglottic regions, extending to the posterior commissure and the right arytenoid. An MRI scan was performed, confirming posterior extension of the cancer, involving the posterior commissure and the right arytenoid, in conjunction with osteosclerotic aspects of the same arytenoid. The paraglottic space was involved as the anterior commissure, without erosion of the perichondrium of the thyroid cartilage. The lesion was in close contact with the cricoarytenoid joint and the thyroarytenoid space was obliterated. No subglottic extension of the cancer was identified ( Fig. 26‑1). The cancer was staged as cT3N0–G2. Following a multidisciplinary team assessment, radiotherapy (RT) was delivered. Two weeks before starting RT, the patient presented severe acute dyspnea and an emergency tracheostomy was carried out. The patient was treated with intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) with a total dose of 70 Gy to the tumor, 63 Gy to the peristomal region and 58 Gy to the bilateral neck (levels II–V). Four months following RT, the MRI showed a recurrent/persistent lesion involving the right glottic and supraglottic region, with infiltration of the paraglottic space but without erosion of the thyroid cartilage. The posterior commissure was involved by the cancer with contralateral extension to the left posterior paraglottic space. The lesion extended also inferiorly into the subglottic region, both anteriorly and posteriorly ( Fig. 26‑2 a,b). The tumor was restaged as yrcT4aN0. Biopsies in microlaryngoscopy confirmed recurrence; therefore, salvage total laryngectomy (STL) was planned. Bilateral neck dissections, total laryngectomy, and prophylactic temporoparietal myofascial free flap was harvested to reinforce the pharyngeal closure in order to prevent complications such as pharyngocutaneous fistula (PCF).

26.2 Surgical Technique

The patient was placed in the head extended position. The surgical procedure was performed under general anaesthesia, with intubation through the previous tracheostomy. A nasogastric feeding tube (NGFT) was inserted.

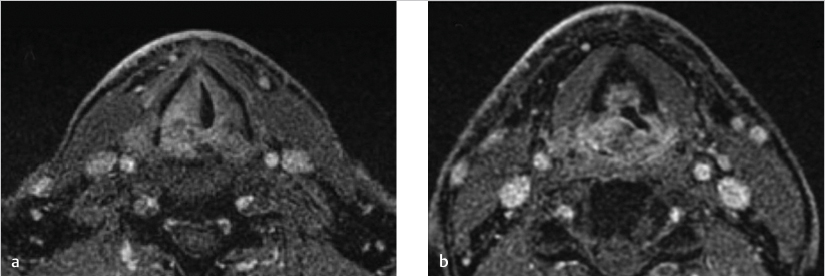

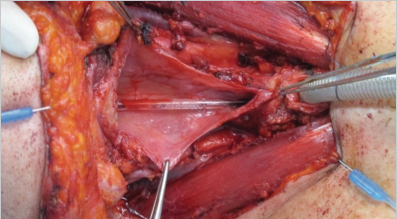

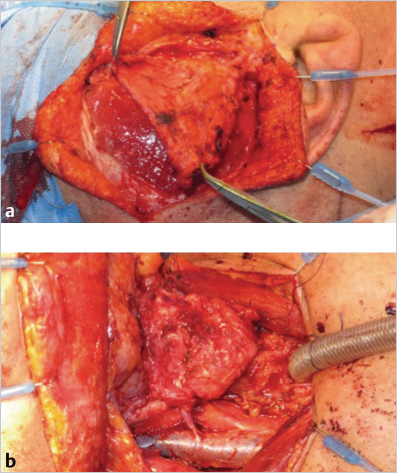

A traditional “apron” incision was performed, which consisted of a bilateral curvilinear midneck incision incorporated with the planned skin excision of the previous tracheotomy. This incision allows to adequately expose the contents of the lateral neck for bilateral selective neck dissection (levels II–IV). After completing the neck dissection, the thyroid gland was released from the trachea on both sides, completely sectioning the isthmus. In this case, there was no suspicion of anterior spread of the tumor; otherwise, the hemithyroid with tumor involvement is left attached to the larynx and is removed along with it. The superior laryngeal artery and vein were identified at the level of the thyrohyoid membrane and sectioned bilaterally. Inferior constrictor muscles were exposed and incised at the insertion on the posterior border of the thyroid cartilage; thus, the superior cornu was skeletonized, thereby releasing the larynx. The hyoid bone was cranially identified and preserved. The hyothyroepiglottic space was dissected and the thyrohyoid membrane was incised at the inferior border of the hyoid bone, in order to access the valleculae. The inferior limit of the resection was performed at the level of the third tracheal ring as needed considering the previous tracheostomy and the subglottic extension of the cancer. The posterior portion of the cricoid was dissected out of the overlying mucosa. The laryngeal frame was finally detached from the anterior esophageal wall through a pharyngotomy ( Fig. 26‑3). A T-shaped closure of the pharynx was carried out. A second layer closure was performed using the inferior constrictor muscles. Finally, the tracheostomy was harvested. The temporoparietal fascia free flap was harvested and insert directly over the pharyngeal closure ( Fig. 26‑4 a, b).

Bilateral cervical and right temporal drains were inserted. The postoperative period was uneventful and the drains were removed within 3 days. Oral intake of liquids started 3 weeks after surgery. The period of hospitalization was 30 days.

The final pathology report showed yrpT4aN0 squamous cell laryngeal carcinoma (G1) with free margins.

No local complications were observed nor any other comorbidities occured. The patient did not have any symptoms of pharyngeal stenosis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree