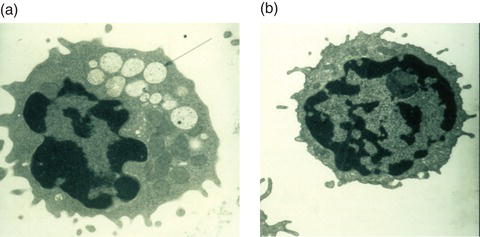

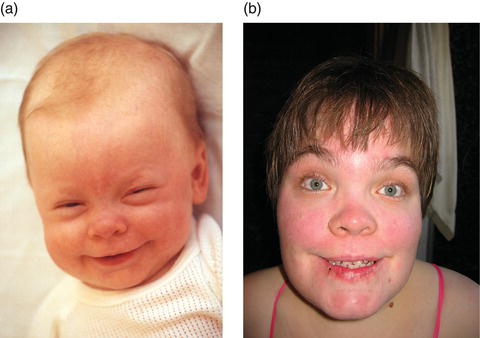

Figure 14.2 A lymphocyte with vacuolated lysosomes from a patient with α-mannosidosis (a), compared to a lymphocyte from a normal control (b). Reproduced from Malm and Nilssen [2] with permission from Biomed Central.

For many of these disorders the accumulation of undigested material results in vacuolization as seen in peripheral blood cells or fibroblasts cells under light or electron microscopy (Figure 14.2). Such accumulation of storage material may not only impair lysosomal function but, as seen in other lysosomal storage disorders, it may also cause pleiotropic effects on cellular functions such as vesicle maturation, synaptic release, endocytosis, exocytosis, Ca++ release and autophagy [8].

Genetic basis

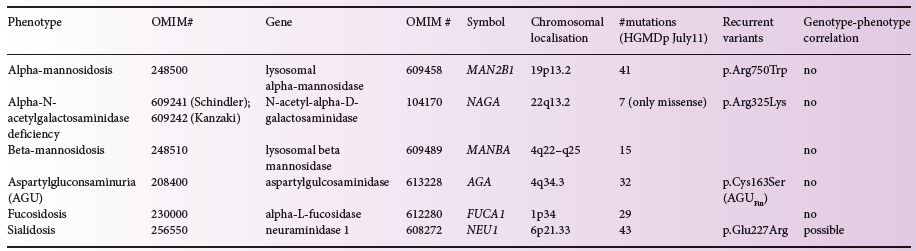

The glycoproteinoses result from mutations in genes that encode the glycosidases involved in glycoprotein degradation (Figure 14.1). The different disorders and their corresponding loci, deficient genes and enzymes are displayed in Table 14.1. Most of the mutations reported in glycoproteinoses are private and occur in single or a few families only, however, exceptions exist. In α-mannosidosis the MAN2B1 substitution p.Arg750Trp has been detected in 64 patients from 20 countries. It constitutes 27.9% of all unrelated disease alleles reported and shows a declining east–west gradient across Europe, indicating eastern European origin [9]. In β-mannosidosis 17 different MANBA mutations have been detected in patients from various ethnic origins. In patients with aspartyglucosaminuria the AGA substitution p.Cys163Ser (AGUFin) accounts for 98% of all AGU alleles in Finland, showing a carrier frequency of 1/30–1/40 [4]. More than 40 NEU1 mutations have been reported in sialidosis patients of varying disease severity of which the substitution p.Gly227Arg appear to be the most frequent as it has been reported in four families from different countries. Seven NAGA mutations have been reported in patients with α-N-acetylgalactosaminidase deficiency, of which the substitution p.Glu325Lys has been detected in several families. In patients with fucosidosis, 29 different FUCA1 mutations have been reported. Most mutations are found in homozygous form indicating a high rate of consanguinity in fucosidosis [6].

Genotype–phenotype relationship

The different glyoproteinoses show variation in clinical severity; however, in general there is no evident correlation between the genotype and the clinical phenotype. This is based on observations of extensive clinical heterogeneity among patients with the same mutation(s), the difference in clinical severity seen in affected siblings and variable clinical presentation in patients homozygous or compound heterozygous for null mutations. A possible exception is sialidosis. Based on cellular and biochemical analysis, Bonten and coworkers [10] classified mutant neuraminidases into three groups: (1) catalytically inactive and not localized to the lysosomes, (2) localized to the lysosomes but catalytically inactive, (3) localized to the lysosomes and with residual activity. Patients with the mild type I form had at least one group 3 mutation. In contrast, patients with the juvenile, severe, type II had mutations belonging to group 1 or 2 [10].

Clinical presentation

The different glycoproteinoses show a wide variation in clinical severity. Accordingly α-mannosidosis (types I, II and III), sialidosis (types I and II), α-N-acetylgalactosaminidase deficiency (types I (Schindler), II (Kanzaki) and III) and fucosidosis (types I and II) have been divided into clinical subtypes. However, rather than specific subtypes, the clinical variation within each disorder appears to represent a continuum from the mild to the severe end of a clinical spectrum. Onset might be congenital but generally ranges from 3 months to 20 years of age. Most glycoproteinoses show infantile onset with a progressing disease course. The glycoproteinoses share in common several Hurler-like clinical features such as mental impairment, speech impairment, growth impairment, delay of motor development, hypotonia, dysostosis multiplex, scoliosis, organomegaly and facial dysmorphism, including macroglossia. Recurrent infections, hearing impairment, ataxia are common to most of these disorders. Additional features such as spasticity, neuroaxonal dystrophy and cortical blindness occur in α-N-acetylgalactosaminidase deficiency type I. However, progressive loss of visual acuity has also been reported in adult patients with other glycoproteinoses.

Laboratory diagnosis

For all glycoproteinoses, initial biochemical screening can be performed by analysis of the urinary oligosaccharide and/or glycopeptide profile by thin-layer or liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). The oligosaccharide and/or glycopeptide composition will indicate glycoproteinosis and may be suggestive of a specific diagnosis. The exact diagnosis, however, will rely on direct measurement of the specific enzyme activity in white blood cells or cultured fibroblast cells. Diagnosis should always be confirmed by targeted sequencing of the patient DNA to identify the disease causing mutation(s) in the gene in question. The carrier status of the parents should be verified. Prenatal diagnosis can be performed by enzyme activity measurements in foetal cells, obtained by chorionic villus sampling at 10–12 weeks of gestation or by mutation analysis using DNA from the same source. Mutation analysis is to be preferred if the parental genotypes are known.

Table 14.1 Disorders of glycaprotein degradation

Figure 14.3 (a) Patient 1 year of age: note large head, prominent forehead, rounded eyebrows, saddle nose and broad mouth. (b) Patient 28 years of age: note large head, prominent forehead, rounded eyebrows, saddle nose, retrognathism, broad mouth with poorly healing sores and widely spaced teeth. Further notice the full hair on head and eyebrows. Normally, she would wear glasses and hearing devices.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree