Case study 134.1

A 53-year-old woman with metastatic colon cancer involving the liver, abdominal pleura and lymph nodes, thoracic spine, and brain. Palliative care consultation was placed for symptoms of vertigo and nausea with projectile vomiting.

Initial treatment included a right-sided hemicolectomy for an obstructing adenocarcinoma of the cecum. She has since received multiple regimens of systemic chemotherapy including phase 1 treatment, as well as undergone craniotomy, stereotactic radiosurgery for brain metastases, and radiation therapy to the thoracic spine. Currently, she is not a candidate for any further chemotherapy and was recently informed of a poor prognosis of 4–6 weeks to live.

The patient is now admitted with a 2–3 day history of nausea, vomiting, vertigo and headache. She attributes her nausea to the administration of opioids and has a history of acathesia with metoclopramide. For nausea, she finds ondansetron to be ineffective and prefers to take lorazepam 0.25–0.5 mg as needed.

Her Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale is: Pain 5, fatigue 6, nausea 7, depression 0, anxiety 0, drowsiness 2, appetite 2, feeling of wellbeing 1, shortness of breath 0, sleep 0.

Her symptoms are significant for left-sided, constant, frontal headache which is worse in the morning hours and non-radiating intermittent chronic mid to low back pain. Headache has persisted for the past 3 days, rates the intensity as a 5/10. She achieves some pain relief with acetaminophen. In addition, she reports vertigo with any type of movement or with standing. Otherwise, the remainder of the review of systems is negative.

Vital Signs include afebrile temperature, pulse 56, respiration rate 17, BP 121/90, O2 saturation was 94% on room air. Physical examination is notable for a chronically ill-appearing woman who is somewhat anxious and talks openly about her concerns. Laboratory values are within normal limits.

1. Which of the following factors may be contributing to the patient’s nausea?

- Gastroparesis

- Increased intracranial pressure

- Anxiety

- Vestibular dysfunction

- All of the above

Nausea with or without symptoms of vomiting is not uncommon in patients with advanced cancer. A stepwise, thoughtful approach is needed for the workup of nausea including a detailed history and physical examination. Once an underlying mechanism is identified, therapy can be tailored to each unique clinical scenario. However, as in the above case, multiple factors may play a role requiring more than one intervention in order to block multiple pathways resulting in emesis.

The first step in the evaluation of nausea includes a thorough history characterizing the symptom with attention for clues to the underlying etiology. Early satiety may indicate gastroparesis, nausea and vomiting in the morning hours with symptoms of head discomfort suggest increased intracranial pressure, nausea relieved by infrequent, large emesis may indicate a bowel obstruction, and a temporal pattern of nausea associated with emotional reaction suggests underlying anxiety. Cancer which has metastasized to the liver, peritoneum, or brain is often associated with nausea.

A complete review of medications is also critical. Research indicates common factors resulting in nausea and vomiting include medications (i.e. opioids, chemotherapy, antibiotics) and constipation. Other factors associated with nausea in cancer patients include infections, metabolic abnormalities, gastroparesis secondary to autonomic dysfunction, radiation especially to the abdomen and pelvis, and bowel obstruction.

Physical examination may provide additional clues regarding the underlying etiology for the nausea and vomiting. Loss of heart rate variability or orthostatic hypotension suggests autonomic dysfunction, evidence of mucositis or thrush may result in oropharyngeal or esophageal irritation, abdominal distention or masses provide evidence of abdominal cancer or malignant ascites, and rectal examination may reveal impaction suggesting constipation.

Nausea and vomiting are the result of stimulation of the following pathways:

- chemoreceptor trigger zone

- cortex with input from the senses

- peripheral pathways via mechanoreceptors in the gastrointestinal tract, vagus and splanchnic nerves, glossopharyngeal nerves, and sympathetic ganglia

- vestibular system.

In cancer patients, common causes of nausea include opioid use, chemotherapy, autonomic dysfunction, and bowel obstruction. Opioid treatment results in nausea and vomiting in 40% of patients by stimulation of the chemoreceptor trigger zone, gastroparesis, constipation, and alterations in vestibular function. In advanced cancer patients with chronic nausea, autonomic dysfunction may result in gastroparesis and constipation. Autonomic failure affects the majority of patients with advanced cancer and is associated with decreased survival.

Autonomic dysfunction in cancer patients has a multifactorial etiology including cachexia, medications including chemotherapy, direct tumor invasion of nerves or paraneoplastic syndrome, and co-morbidities such as diabetes or heart failure.

Measures to prevent constipation and avoid medications which may exacerbate autonomic dysfunction should be implemented.

2. To control the patient’s intractable nausea with vomiting, which medication would you initiate?

- Metoclopramide

- Dexamethasone

- Haloperidol

- Diphenhydramine

- Ondansetron

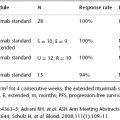

Two approaches to the management of nausea and vomiting have been proposed. One approach involves treatment based on underlying mechanism and found to be effective in up to 90% of patients with advanced disease. Others have proposed initiation of an empirical anti-emetic regimen, usually a D2 antagonist, irrespective of the underlying etiology. No head-to-head comparison of the two strategies has been studied to date.

In clinical practice, patients with advanced cancer often have symptoms of nausea and vomiting due to multiple underlying factors. All potential reversible etiologies must be assessed and treated while simultaneously administering an antiemetic to control symptoms. A D2 antagonist such as metoclopramide or haloperidol would be a sensible empiric treatment for nausea.

In the case presentation, the patient has a history of acathesia to metoclopramide. Her history of head discomfort and early morning nausea with MRI revealing progression of brain metastasis would argue to initiate steroids as first line therapy. With the above change in treatment, patient has less projectile vomiting but continues to be symptomatic despite a trial of several anti-emetic medications.

In the next 48 hours, the patient develops increase confusion with periods of agitation at night resulting in distress to the patient, family, and nursing staff. Family at bedside observes that agitation has a temporal relationship with the administration of lorazepam which causes brief sedation followed by agitation and confusion. Memorial delirium assessment scale was conducted by palliative care fellow at beside and found to be 10/30.

3. Which of the following treatments is the first line therapy to control agitation secondary to underlying delirium?

- Repeat dose of lorazepam

- Haloperidol

- Chlorpromazine

- Diphenhydramine

- Physical restraints

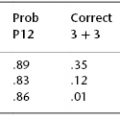

Delirium is common symptoms at the end of life and results in distress not only for patients but also for their family and healthcare providers. Delirium is characterized by a disturbance in consciousness with an inability to focus, shifts in attention, perceptual disturbances which fluctuating over time. The majority of patients have a good recollection of their experience while delirious resulting in distress. Appropriate interventions are needed to treat underlying precipitation factors including infections, dehydration, electrolyte abnormalities such as hypercalcemia and hyponatremia, organ failure, medications such as opioids and benzodiazepines, intracranial disease, as well as a number of other factors and must be initiated rapidly. In cancer patients, delirium is frequently underdiagnosed resulting in undertreatment. Several clinical tools to assess for delirium exist, but only the Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale (MDAS) and the brief observational Nursing Delirium Screening Scale (NuDESC) are both diagnostic and able to quantify the severity of delirium, allowing patients to be monitored over time.

Limited research exists examining pharmacological treatment of delirium. In hospitalized patients with AIDS, Breitbart et al. performed a seminal double-blind, randomized comparison trial of haloperidol, chlorpromazine, and lorazepam. Both haloperidol and chlorpromazine were effective; however, chlorpromazine was associated with a significant decline in cognitive function. The arm receiving lorazepam was stopped early secondary to side effects including excessive sedation, worsening mentation and disinhibition, and ataxia. The combination of haloperidol with lorazepam have been proposed for the treatment of agitated, delirious patients in order to minimize extrapyramidal side effects but more studies are needed. In addition, atypical antipsychotic medications secondary to decreased risk of extrapyramidal adverse effects are being evaluated in the treatment of delirium; however, high quality randomized controlled trials are lacking.

The same day, the patient’s primary oncologist visits the patient who is agitated and distressed. He recommends transfer to an inpatient Palliative Care Unit and consideration for palliative sedation.

4. Which of the following conditions is palliative sedation clearly indicated?

- Chronic nausea

- Anxiety and depression

- Terminal delirium with agitation

- Transient respite care

- Existential pain

Patient is transferred to the acute Palliative Care Unit and reversible causes of delirium were worked-up and treated by an interdisciplinary team. Patient remained agitated despite administration of haloperidol (>10 mg/day) and a trial of chlorpromazine was initiated and found to be ineffective in controlling symptoms. No reversible etiology was noted and the patient was diagnosed with terminal delirium. Discussions with the patient’s family caregivers about palliative sedation to control symptoms at the end of life were deliberated and agreed upon.

5. Which of the following medications titrated to control symptoms would be appropriate for palliative sedation?

- Intermittent lorazepam as needed for agitation

- Continuous midazolam titrated to control symptoms

- Continuous morphine drip titrated to control symptoms

- Scheduled haloperidol every 4 hours

- Scheduled haloperidol every 4 hours with intermittent lorazepam as needed for agitation

Palliative sedation is a treatment of last resort for refractory symptoms in patients with cancer. Symptoms are refractory when they are inadequately controlled despite aggressive treatment which does not compromise consciousness. An interdisciplinary team with specialists in pain and symptom management should ideally be involved in assessment and treatment of symptoms prior to categorizing them as refractory.