11 Locally Intermediate Glottic Cancer: Chemoradiotherapy

Abstract

A case report of locally intermediate glottic cancer, cT3N0M0, stage III, is presented with discussion of the multidisciplinary evaluation, options for preserving the larynx, and the treatment course. Endoscopy revealed a left glottic mass extending to the left false cord, arytenoid, and aryepiglottic fold. The vocal fold was fixed. CT imaging demonstrated involvement of the left paraglottic space with no cervical lymphadenopathy. Swallowing function was normal with no penetration or aspiration, and vocal quality was hoarse with moderately reduced intensity. Concurrent chemoradiation was chosen by the patient whose employment entailed high occupational voice demands. The patient received a cumulative radiation dose of 7,000 cGy to gross disease, 6,125 cGy to the uninvolved larynx, and 5,600 cGy to bilateral cervical nodal levels II to IV that was planned and delivered using image-guided volumetric modulated arc therapy. Chemotherapy concurrent with radiation was seven weekly doses of cisplatin 40 mg/m2 with hydration, antiemetics, and pain management. The patient required enteral nutritional support until 6 weeks following completion of treatment. PET/CT imaging at 12 weeks demonstrated non-fluorodeoxyglucose avid posttreatment changes indicative of a complete response. The surgical and nonsurgical larynx preservation treatment options, standard of care recommendations, expected outcomes, and supporting literature are discussed. Accurate staging and baseline assessment of swallowing and voice function are emphasized. Other factors to consider in the treatment decision are comorbidities, patient preference, and expectations for long-term voice quality.

11.1 Case Report

A 57-year-old Caucasian male presented with a 3 month history of progressive sore throat and hoarseness. He was an active smoker of one pack of cigarettes per day for 42 years and social use of alcohol. He also noted occasional shortness of breath at night when lying flat. He denied dysphagia or weight loss. He worked as a railroad manager with high occupational voice demands. His medical history was significant for hypertension treated with metoprolol and valsartan, and atrial fibrillation anticoagulated with rivaroxaban. He was referred to an Otolaryngologist, and flexible laryngoscopy revealed a left glottic mass extending to the left false cord, arytenoid, and aryepiglottic fold. The left vocal fold was fixed in the median position. CT of the neck with contrast showed an enhancing mass involving the left glottis and aryepiglottic fold with involvement of the left paraglottic space. There was no cervical lymphadenopathy on physical examination or CT of the neck. He underwent direct laryngoscopy with biopsy of the laryngeal mass. Pathology reported invasive squamous cell carcinoma. CT of the chest showed no suspicious pulmonary nodules, and the clinical staging by the seventh edition of AJCC was cT3N0M0 (stage III).

The patient was seen in a multidisciplinary head and neck clinic by an otolaryngologist, radiation oncologist, medical oncologist, and speech-language pathologist (SLP). Fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing demonstrated normal baseline swallow function with no penetration or aspiration across all consistencies. The patient’s vocal quality was moderately rough and hoarse with mildly reduced intensity. Surgical and nonsurgical treatment options were discussed with the patient, including total laryngectomy, partial laryngectomy, or definitive chemoradiation with weekly cisplatin.

Larynx-preserving surgery for this cancer would require a supracricoid laryngectomy, which includes removal of the true and, false vocal cords, supraglottis, and pre-epiglottic space, and may be extended to include one arytenoid or the epiglottis.s. Literatur Anatomic contraindications to this procedure are bilateral arytenoid involvement, subglottic extension of the cancer more than 1 cm anteriorly and 0.5 cm posteriorly, cricoid cartilage involvement, base of tongue involvement, and extension into the hypopharynx or the pyriform apex. Functional considerations are aspiration and breathy voice resulting from surgery. Patients with pulmonary impairment are poor candidates for larynx-preserving surgery, because aspiration is common and the availability of speech-language pathology in rehabilitation is a critical component of surgical decision-making. Evaluation of pulmonary function is critical to successful surgery, with the ability to climb two flights of stairs without dyspnea an excellent indicator of the patient’s ability to tolerate the functional sequelae of partial laryngectomy. Because surgery results in a U-shaped laryngeal inlet, dysphonia results with a voice that is breathy and of low volume.

The patient elected for treatment with definitive chemoradiation and underwent CT and MRI simulation. Pretreatment dental evaluation was performed.

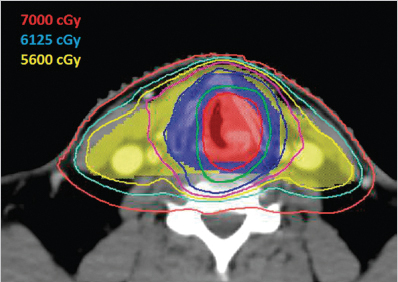

The patient completed successfully 7 weeks of concurrent radiation and cisplatin chemotherapy. The cumulative dose of radiation was 7,000 cGy to gross disease, 6,125 cGy to the uninvolved larynx, and 5,600 cGy to bilateral cervical nodal levels II to IV ( Fig. 11‑1).

Simultaneous integrated boost technique was used with 35 daily fractions. Treatment was planned and delivered using image-guided volumetric modulated arc therapy (a type of intensity-modulated radiotherapy) with 6 MV photons and daily cone-beam CT guidance. The patient received all seven planned doses of weekly cisplatin at 40 mg/m2 with routine IV hydration and antiemetics including ondansetron and dexamethasone. He developed grade 3 mucositis and grade 2 dysphagia, nausea, vomiting, and dysgeusia. These side effects led to inadequate oral intake with a weight loss of 24 pounds (12% body weight), so that a temporary nasogastric tube was placed. His pain was controlled with gabapentin, oxycodone, and a fentanyl patch. He also developed grade 3 dysphonia by the end of the treatment. The nasogastric tube was removed at 3 weeks posttreatment. He required frequent IV hydration and magnesium repletion for 6 weeks posttreatment.

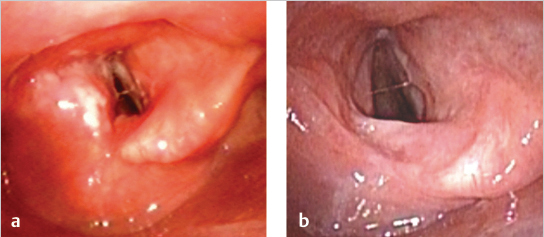

Flexible laryngoscopy revealed that the patient had a complete clinical response to treatment ( Fig. 11‑2 a, b).

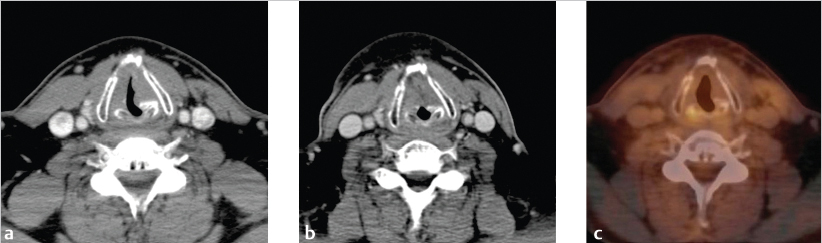

The patient also successfully stopped smoking. At 3 months posttreatment, CT of the neck with IV contrast demonstrated decreased volume of the glottic mass and posttreatment changes ( Fig. 11‑3 b). Subsequent PET/CT demonstrated non-FDG (fluorodeoxyglucose) avid posttreatment changes with only physiologic FDG uptake in the larynx ( Fig. 11‑3 c).

At 12 months posttreatment, the patient had no evidence of disease and noted mild dysphagia, dysphonia, and lymphedema of the anterior neck. He was only partially compliant with SLP follow-up and swallowing exercises. He underwent physical therapy for the lymphedema with partial improvement.

11.2 Discussion

Accurate staging and functional assessment are critical in the evaluation of patients with glottic cancer. Treatment options typically include surgical or nonsurgical management for patients with stage T1 to T3 cancer, whereas total laryngectomy is strongly favored for patients with stage T4a cancer or severe baseline laryngeal dysfunction. For early glottic cancer (stage T1–T2 N0), patients may be treated with larynx-preserving or definitive radiotherapy with similar, excellent outcomes. TLM is often favored for unilateral stage T1aN0 cancer to preserve function of the vocal cord. Definitive radiotherapy is often favored for bilateral cancer (stage T1b) or cancer involving the supraglottis (stage T2). In this setting, radiotherapy is typically delivered using two opposed lateral beams to the larynx alone (not neck nodes) using a hypofractionated regimen of 6,300 to 6,525 cGy in 28 to 29 fractions. 2 , 3

For intermediate-stage glottic cancers (T3 or N+), treatment options typically include definitive chemoradiotherapy, total laryngectomy, or in select cases partial laryngectomy.

Total laryngectomy remains the gold standard against which all organ preservation techniques are measured and, by removing the larynx and thus separating inspiration from swallowing, is associated with a lower incidence of late toxicity. In Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program (SEER) Medicare data, surgery appears to be associated with improved survival, which may be a result of a lower odds of late pneumonia in surgical patients, which was associated with the greatest risk of death at 5 years. 4 , 5 However, total laryngectomy is disfiguring and results in a permanent tracheostoma, which has functional and psychological consequences. 6

Surgical techniques that preserve the larynx (hemilaryngectomy, supraglottic laryngectomy, and supracricoid laryngectomy) preserve voice, avoid a tracheostoma, and offer the potential to avoid chemotherapy and to use radiation therapy (RT) in the adjuvant setting, with survival rates reported to be similar to that following total laryngectomy. 1 Larynx conservation surgery requires the patient to use compensatory strategies to protect the airway, and is associated with a high incidence of dysphagia and aspiration, but with careful patient selection a low incidence of morbidity and severe treatment-related complications, which is critical to a successful outcome. 7 , 8 Intelligible speech is preserved, but severe dysphonia results, which may impact patient-reported emotional, physical, and functional outcomes. 9 Compared to total laryngectomy, supracricoid laryngectomy is associated with an initial protracted period of swallowing difficulties and swallowing therapy, but speech intelligibility is rated as similar. 10 When medical and anatomic considerations are taken into account, less than one-third of patients are suitable candidates for larynx conservation surgery. 11

Nonsurgical larynx preservation approaches for intermediate-stage cancer of the glottis include concurrent chemoradiation, neoadjuvant (induction) chemotherapy followed by radiation, and RT alone. Based on the results of a meta-analysis of chemotherapy added to standard local curative treatment in more than 17,000 patients with cancer of the head and neck 12 and prospective randomized controlled trials in larynx cancer, 13 , 14 , s. Literaturconcurrent chemoradiation has been shown to offer a significant advantage over the approaches of induction or radiation alone for preserving the larynx and achieving locoregional control.

The Veterans Affairs (VA) Laryngeal Cancer Study, published in 1991, demonstrated equivalent survival for advanced cancer of the larynx treated with total laryngectomy or with induction chemotherapy followed by radiation, allowing for laryngectomy in nonresponders. 13 Salvage laryngectomy was ultimately performed for 56% of patients with T4 cancer, compared to 29% for T1 to T3 cancer, and was more frequently associated with glottic than supraglottic subsite, and with gross cartilage invasion than no cartilage invasion. 13 This higher local failure rate for T4 cancers led to the exclusion of high-volume T4 cancers (penetration through cartilage or into deep tongue musculature) from subsequent randomized trials and therefore combined chemoradiation larynx preservation approaches were limited to selected T4a cancers. By contrast, the data for intermediate-stage larynx cancer indicate equivalent survival outcomes with excellent locoregional control. Favorable results of chemoradiation were demonstrated in the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) Trial 91–11, which largely excluded T4 cancers and demonstrated improved locoregional control rates with concurrent chemoradiation therapy. 14 These data established larynx preservation with chemoradiation as a standard of care for intermediate-stage larynx cancers.

Concurrent cisplatin and radiation is endorsed in guidelines 16 as the recommended nonsurgical approach for larynx preservation based on high-level evidence and is the most commonly used approach in the United States. The RTOG 91–11 U.S. Intergroup trial of 547 patients directly compared the three approaches; concurrent cisplatin and RT, induction cisplatin/fluorouracil followed by RT, and RT alone in patients with locally advanced cancer of the glottis or supraglottis. 14 , 15 Most patients had stage III cancer, stage distribution was 79% T3, 50% N0, and 21% N1, and thus the results are applicable to this case of T3N0 cancer of the glottis. The long-term results of RTOG 91–11 showed that overall survival was similar with all three approaches but concurrent treatment was associated with a 54% relative risk reduction of laryngectomy compared with RT alone (hazard ratio [HR]: 0.46; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.30–0.71; p < 0.001) and a 42% risk reduction compared to induction chemotherapy (HR: 0.58; 95% CI: 0.37–0.89; p = 0.005). Surprisingly, induction chemotherapy added to RT had no effect on laryngectomy rate compared to treatment with RT alone. The difference in local and locoregional control followed a similar pattern demonstrating clear superiority of concurrent chemoradiation. Less acute in-field toxicity is observed with the induction approach and with RT alone, and these treatment options may be preferred based on individual patient characteristics and the expertise of the treating team. The induction approach is preferred in some geographic regions outside of North America based on a series of induction trials conducted in Europe. 17 , 18 , 19 Treatment-related late toxicity is a concern with larynx preservation with surgery or with concurrent chemoradiation. The late-effects toxicity grading system (NCI/RTOG/UICC) may be inadequate to discriminate differences among treatment groups following radiotherapy or combined chemotherapy and radiotherapy. For example, there were no differences in the incidence of laryngopharyngeal/esophageal and soft-tissue late toxicity occurring between treatment groups in the RTOG 91–11 trial and no difference in speech and swallowing function assessments. However, the 10-year follow-up report of RTOG 91–11 found an increase in non-cancer-related deaths in patients treated with concurrent chemoradiation beyond 5 years. 15 This unexplained outcome could possibly be a consequence of unrecognized late toxicity. High crude rates of late laryngeal and pharyngeal dysfunction were reported in a combined analysis of multisite RTOG chemoradiation trials. 20 The data in all of these reports come from trials performed over two decades ago using two-dimensional RT. Whether the risk of late effects is the same today with the use of modern radiation techniques and aggressive supportive care including speech and swallowing therapy is not known. It is clear that patient selection is a key factor for achieving an optimal result of surgical or nonsurgical organ preservation.

Cisplatin is the radiosensitizer recommended for administration concurrent with RT. Carboplatin is recommended for patients with medical contraindications to cisplatin. There are insufficient data to support the use of any other radiosensitizer. Prospective clinical trials in cancer of the larynx have used once every 3 weeks. high-dose (100 mg/m2) cisplatin administered every three weeks once every three weeks during the course of RT. Alternative weekly dosing (40 mg/m2) has come into practice to reduce the risk of nephrotoxicity, ototoxicity, nausea/vomiting, and to insure adequate prehydration of patients treated in the outpatient setting. The weekly schedule has been studied in nasopharyngeal cancer and the two schedules appear to have equivalent efficacy. In the treatment of non-nasopharyngeal cancer, there is a clinical impression of equivalent efficacy of the two dosing schedules when a minimum total dose of 200 mg/m2 is given. This has led to the frequent use of weekly cisplatin dosing in clinical practice. A recent meta-analysis of 52 studies (4,209 patients) of concurrent cisplatin and RT for definitive or adjuvant treatment of head and neck cancer revealed that there was no difference in overall survival or response rate among patients treated with weekly or high-dose cisplatin. 21 The weekly regimen in the definitive treatment setting was associated with higher treatment compliance and significantly less severe and life-threatening (grades 3 and 4) myelosuppression (leucopenia, neutropenia), nephrotoxicity, and nausea/vomiting. In the adjuvant setting, investigators at the Tata Memorial Hospital randomized 300 non-nasopharyngeal cancer patients to weekly (30 mg/m2) cisplatin or every 3-week, high-dose (100 mg/m2) cisplatin and RT. 22 There was a significant difference in the cumulative 2-year locoregional control rate, 58.5% versus 73% favoring 3-weekly cisplatin but no significant difference in median progression-free or overall survival outcomes. Toxicity was substantially higher with the high dose treatment. No other randomized non-nasopharyngeal cancer studies have been reported. Additional prospective studies addressing this question are unlikely given the resources that would be required to power a trial to show a small difference or noninferiority of the weekly low-dose schedule. Moreover, cisplatin efficacy is totally dose dependent, not schedule dependent. Thus, at present, a weekly dose of 40 mg/m2 is viewed as a potentially safe and equally effective alternative to three-weekly high-dose treatment as was used in the case presented.

Baseline functional assessment is very important in the discussion of treatment options for patients with intermediate-stage glottic cancers, and multidisciplinary dialogue is critical. In the case presented here, the patient attended a multidisciplinary clinic including SLP, and he was found to have excellent baseline swallow function and moderate baseline dysphonia. Given these factors, as well as his young age, limited comorbidities, and availability of appropriate support and expertise, the multidisciplinary team anticipated a relatively high likelihood of successful larynx preservation. His occupational voice demand and personal preferences were also taken into account in his treatment decision.

Radiation techniques for treatment of intermediate- or advanced-stage glottic cancers are more complex than those for early-stage glottic cancers, requiring intensity-modulated radiotherapy with many beams or several continuous arc beams. The dose is typically approximately 70 Gy to gross disease, with lower doses to at-risk areas of the larynx, pharynx, and neck. Bilateral neck nodes should be included in the treatment volume, even for clinically node-negative patients. Conventional fractionation is preferred with approximately 2 Gy per fraction to limit the risk of late toxicities. Image guidance should be utilized when available. Whenever possible, the radiation plan should spare the parotid and submandibular glands, pharyngeal constrictors, and oral cavity.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree