3 Pathology Chronic Venous and Lympho-Venous Insufficiency Lymphedema is a very common and serious condition, affecting at least 3 million Americans. It occurs if the transport capacity (TC) of the lymphatic system has fallen below the normal lymphatic load (LL; see Chapter 2, Mechanical Insufficiency), resulting in an abnormal accumulation of water and proteins principally in the subcutaneous tissues. Lymphedema may be present in the extremities, trunk, abdomen, head and neck, external genitalia, and internal organs; its onset is gradual in some patients and sudden in others. Most patients in the Western Hemisphere develop lymphedema after surgery and/or radiation therapy for various cancers (breast, uterus, prostate, bladder, lymphoma, melanoma), in which case it is referred to as secondary lymphedema. Other patients develop it without obvious cause at different stages in life (primary lymphedema), and still others develop it after trauma or deep vein thrombosis. In developing countries, parasites (filariasis) account for millions of cases. Lymphedema is serious because of its long-term physical and psychosocial consequences for patients; it continues to progress if left untreated. If lymphedema combines with other pathologies (cardiac and venous insufficiency, chronic arthritic conditions, etc.), the pathophysiological effects are further exacerbated due to the additional stress placed on the already compromised lymphatic system (see Chapter 2, Combined Insufficiency). Its cosmetic deformities are difficult to hide, and complications do occur frequently (fibrosis, cellulitis, lymphangitis, lymphorrhea, etc.). Lymphedema is also serious because of the pervasive lack of medical expertise in the diagnosis and treatment of this condition and the tendency of clinicians to trivialize lymphedema in patients who have been treated for cancer. No specific studies on the incidence of lymphedema have been performed to date, and estimated rates reported in the literature vary widely. Worldwide, 140 million to 250 million cases of lymphedema are estimated to exist, with filariasis, a parasitic infestation (see Secondary Lymphedema later in this chapter), being the most common cause. In the United States, the highest incidence of lymphedema is observed following breast cancer surgery, particularly among those who undergo radiation therapy following axillary lymph node dissection. Other than skin cancer, breast cancer is the most common type of cancer among women in the United States. All women are at risk for developing breast cancer. A woman’s chance of developing breast cancer increases with age. The majority of breast cancer cases occur in women over 50 years of age. Although breast cancer is less common at a young age, younger women tend to have more aggressive types of breast cancer than older women, which may explain why survival rates are lower among younger women. Incidence also varies within ethnic groups and geographical location within the United States (Table 3.1). Table 3.1 Incidence of breast cancer by age

Lymphedema

Definition

Incidence of Lymphedema

By age 30 | 1 out of 2212 |

By age 40 | 1 out of 235 |

By age 50 | 1 out of 54 |

By age 60 | 1 out of 23 |

By age 70 | 1 out of 14 |

By age 80 | 1 out of 10 |

Ever | 1 out of 8 |

Source: National Cancer Institute, 1999

Generally, it can be said that 1 in 8 women in the United States will develop breast cancer during the course of their lives. (More information can be found on the National Institute for Cancer Website at http://cancer.gov/cancerinformation, accessed June 9, 2012.)

Other cancer survivors at risk for lymphedema include those who have undergone surgery and/or radiation treatment for malignant melanoma of the upper or lower extremities; prostate cancer; gynecologic cancers; ovarian, testicular, and prostate cancers; and colorectal, pancreatic, or liver cancers. Some studies report the incidence of lower extremity lymphedema (and/or genital lymphedema) after radical lymph node dissection in prostate cancer to be more than 70%.

It is generally thought that the more lymph nodes are removed during any surgical procedure, the higher the incidence of lymphedema. The true numbers of patients suffering from any form of lymphedema are unknown.

Most statistics are available on the incidence of upper extremity lymphedema following breast cancer surgery in women. Studies show incidences varying from 6–7% of breast cancer patients (a report in the April 1984 issue of Breast Cancer Digest found that ~50–70% of patients who have had axillary node surgery will develop lymphedema). In general, studies with longer follow-up show higher incidence and more severe swelling. Some authors feel that with the more conservative surgical procedure (modified radical mastectomy), the incidence has decreased. Surgeons hope that the sentinel node procedure (see discussion in Secondary Lymphedema later in this chapter) will reduce lymphedema because it removes fewer nodes. Presently, there is not enough follow-up information available to state this with certainty.

Based on the numbers above and other statistics, it is estimated that 2 million to 3 million secondary and 1 million to 2 million primary lymphedema cases are currently in existence in the United States.

Lymphedema may develop anytime during the course of a lifetime in primary cases. Secondary cases may occur immediately postoperative, within a few months, a couple of years, or 20 years or more after surgery.

Lymphedema Incidence among Non-Breast Cancer Patients

Lymphedema is recognized as a significant breast cancer survivorship issue; however, this chronic, progressive condition can also occur after the treatment of other solid tumors particularly those requiring lymph node dissections. While there have been several studies examining the incidence and risk factors for lymphedema following the treatment of breast cancer,1 less is known about lymphedema following the treatment of other tumors.

Our research group performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of the oncology-related medical literature to determine the reported incidence of and risk factors for lymphedema after treatment of cancers other than breast carcinoma.2 We searched three major medical indices (MEDLINE, Cochrane Library databases, and Scopus) to identify all prospective studies of post-treatment lymphedema published from 1972 to 2010. These studies were identified and categorized according to the type of malignancy. Detailed information related to the surgical procedure, radiation therapy, follow-up interval, lymphedema measurement criteria, and lymphedema incidence were extracted from each article. The Quality Assessment Tool for Diagnostic Accuracy Studies3 was used to score individual study quality, with scores ranging from 0 (worst quality) to 14 (best quality). Overall estimates of lymphedema incidence were calculated using weighted averages, on the basis of study size, for each type of malignancy.

Forty-seven eligible studies were identified that evaluated secondary lymphedema in patients with melanoma (n = 19 studies), gynecologic cancer (n = 25), genitourinary cancer (n = 8), head and neck cancer (n = 1), and sarcoma (n = 1). The median (range) study quality scores were as follows: melanoma, 7 (4–10); gynecologic cancer, 7 (4–10); genitourinary cancer, 5 (3–9); head and neck cancer, 5 (4–10); and sarcoma, 7. Of the 8341 patients included in these reports, 16% had been diagnosed with lymphedema, with a reported incidence of 0%–73%. This variability in the reported incidence can be attributed to the significant heterogeneity among the studies’ clinical lymphedema definitions, lymphedema measurement methods, and follow-up durations.

Patients with sarcoma had the highest pooled incidence of lymphedema (30%), followed by patients with gynecologic cancer (20%), melanoma (16%), genitourinary cancer (10%), and head and neck cancer (4%) (Table 3.2). Among patients with melanoma, those undergoing axillary lymph node dissection had a much lower incidence of lymphedema (5%) than did those undergoing inguino-femoral lymph node dissection (28%). Overall, 2837 patients in 22 studies underwent pelvic lymph node dissection for various malignancies; their incidence of lymphedema was 22%. The incidence of lymphedema among 1716 patients in 18 studies treated with radiation was 31%.

Lymphedema Genetics

Hereditary Lymphedema

In the United States and Europe, the predominant presentation of lymphedema is as a secondary condition following cancer treatment. However, there are also forms of primary lymphedema which run in families (hereditary) and have been recognized as early as 1892 by Milroy.4 Despite this long history, it is only in the last 10–15 years with the explosion in molecular biology and specifically molecular lymphology that advances in lympho-vascular genetics have taken place.5 The true incidence is not clear because standardized evaluation protocols do not exist, few centers are equipped to focus on patients with genelinked lymphatic abnormalities, and testing options are limited. In patients with primary lymphedema, based on available evidence including testing, it is reasonable to estimate that 5%–10% are hereditary. There is a slightly higher incidence in females with males generally presenting at birth and females at puberty; however, this feature is not of diagnostic value. Examination of the lymphatic system abnormalities in these patients has demonstrated developmental aplasia, hypoplasia, and hyperplasia of the lymphatic vessels and nodes as the underlying cause of the lymphedema. The majority of patients described so far have autosomal dominant mutations meaning that a single mutated gene passed on to the next generation is sufficient to cause disease. Others are autosomal recessive requiring a mutated gene from each parent. Some of these genes have reduced penetrance meaning that even though the gene may be present, its effect may not be evident. There are also genes that have varied levels and types of presentation. These features understandably require careful evaluation by the clinical team.

The Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) catalog focuses mainly on inherited genetic diseases.6 This catalog is frequently updated and easily searchable. Focusing on lymphedema or lymphangiectasia, there are almost 40 syndromes that have lymphedema as a component, and many of these have multiple phenotypic abnormalities of the lymphatic system and a variety of other systems involved.6 There are also additional syndromes that do not yet have entries in OMIM.7

Known Genes

There are seven genes implicated so far in syndromes with either lymphedema as a primary phenotype or as a consistent feature, two genes without a specifically defined associated lymphedema syndrome, and six syndromes with chromosomal abnormalities (Table 3.3). These mutations and chromosomal abnormalities are spread across the entire human genome, and it appears unlikely that genes yet to be discovered will be segregated to more focused areas. It is interesting to note that all the mutations so far have been found on the q or long arm of the chromosomes. Whether this will also be the case for new genes remains to be seen.

Approach to Clinical Evaluation

Although major advances in understanding the role of specific genes in development of the lymphatic system and lymphedema-related syndromes have occurred recently, defining the mechanistic link between the clinical phenotype and the genotype remains incomplete. The first step in approaching the patient is detailed evaluation by the clinical team of the history and physical examination, which remains paramount in phenotyping the patient. This phenotyping should also include imaging of the lymphatic system to define more precisely the anatomical and functional defects. Without clear distinctions between patients with specifically defined syndromes, the sophisticated genetic techniques will not be as powerful.

The second step is to determine the genotype. This task will largely fall to the geneticist or knowledgeable physician on the team. After obtaining consent from the patient, a requirement due to the type of information which can be revealed by analysis of genetic material regardless of whether the patient is in a study or not, a sample is collected to isolate DNA. This sample can be blood, scrapings of cheek cells, mouthwash following vigorous rinsing, or a small piece of tissue obtained from an operative procedure. Standardized protocols are used to isolate DNA from these samples. The number of family members who are available and whether the search is for a specific known gene(s) or for a new gene will determine what type of analysis is employed. Sophisticated linkage analysis may take place, whole genome, specific gene, or exome sequencing may be utilized, or newer gene-chip technology could be used. Different clinical centers have varying levels of expertise with these techniques and some specific gene testing is commercially available. Associated costs should be considered.

The Future

From studies in mice it is known that there are many more genes that impact lymphatic system development and function which do not yet have a corresponding gene in man, or the corresponding mutations have yet to be discovered. There are also many human syndromes, which so far have no known associated gene defect. These areas are clearly where future advances will be made. In addition, improvements in availability and sophistication of genetic testing, more comprehensive and careful phenotyping of the physical manifestations, and diagnostic imaging of the lymphatic system by clinicians should move the field forward.

The goal of investigating the genetics of lymphedema-related syndromes is to translate these basic science discoveries back into the clinic and impact lives of patients. Genes crucial for the growth and development of the lymphatic system can be identified, then this knowledge can be harnessed to stimulate (or inhibit) lymphatic system growth and function when and where it is defective or dysfunctional. In addition, by carefully defining the syndromes that manifest lymphedema, specific genetic treatment plans can be devised including pinpointing of the optimal timing to correct or ameliorate the defects. Unfortunately, the recent history of gene therapy has yet to yield the anticipated success and practical applications and our understanding of the specific genes, expressions, interactions, and context for future treatment remains limited.

Etiology of Lymphedema

Lymphedema can be classified as primary or secondary, based on underlying etiology. However, this classification usually has little significance in determining the method of treatment (Table 3.4).

Table 3.4 Etiology of lymphedema

Primary lymphedema | Secondary lymphedema |

• Aplasia • Hypoplasia • Hyperplasia (lymphangiectasia/megalymphatics) • Fibrosis of lymph nodes • Agenesis of lymph nodes • Congenital • < 35 years of age: lymphedema praecox • > 35 years of age: lymphedema tarda | • Dissection of lymph nodes • Radiation • Trauma • Surgery • Infection • Malignancies • Chronic venous insufficiency • Immobility • Self-induced |

Fig. 3.1 Reduced transport capacity in the subclinical stage of lymphedema. LL, lymphatic loads or lymph volume; LTV, lymph time volume (TC = LTVmax); TC, transport capacity of the lymphatic system.

Primary Lymphedema

Primary lymphedema represents a developmental abnormality (dysplasia) of the lymphatic system, which is either congenital or hereditary. It can present as a variety of abnormalities.

Hypoplasia. This most common form of dysplasia refers to the incomplete development of lymph vessels; that is, the number of lymph collectors is reduced, and the diameter of existing lymph vessels is smaller than normal.

Hyperplasia. The diameter of lymph collectors is larger than normal in this dysplasia (lymphangiectasia or megalymphatics). The dilation of the lymph collectors results in a malfunction of the valvular system within the collectors, which often leads to lymphatic reflux.

Aplasia. The absence of single lymph collectors, capillaries, or lymph nodes associated with this abnormality may be a cause for the development of primary lymphedema.

Fibrosis of the inguinal lymph nodes (Kinmonth syndrome) presents an additional cause for the onset of primary lymphedema. The fibrotic changes primarily affect the capsular and trabecular area of the involved lymph nodes. This may affect lymph transport in the afferent lymph collectors.

With the understanding of basic lymphatic system physiology, it becomes evident that the transport capacity of the lymphatic system in all the abnormalities listed above is reduced (Fig. 3.1). As discussed in Chapter 2, lymphedema occurs if the transport capacity of the lymphatic system falls below the normal lymphatic load.

Although the developmental abnormalities are present at birth, lymphedema may develop at some point later in life. It may not develop at all as long as the (reduced) transport capacity of the lymphatic system is sufficient to manage the lymphatic loads. Primary lymphedema is often classified by the age of the patient at the onset of swelling.

Congenital lymphedema is clinically evident at birth or within the first 2 years of life. A subgroup of patients with congenital lymphedema has a familial pattern of inheritance, which is termed Milroy’s disease. If primary lymphedema presents after birth but before the age of 35, it is called lymphedema praecox, which is the most common form of primary lymphedema and most often arises during puberty or pregnancy. Lymphedema tarda is relatively rare and develops after the age of 35.

Primary lymphedema almost exclusively affects the lower extremity (unilateral and bi-lateral) and involves mostly females. The swelling usually starts at the foot and ankle and gradually involves the remainder of the extremity. It may occur without any known impetus or may develop after minor trauma (insect bites, injections, sprains, strains, burns, cuts), infections, or immobility. These triggering factors produce additional stress to the already impaired lymphatic system, resulting in mechanical insufficiency (Fig. 3.2).

Secondary Lymphedema

The mechanical insufficiency present in secondary lymphedema is caused by a known insult to the lymphatic system.

Most common causes for secondary lymphedema include surgery and radiation, trauma, infection, malignant tumors, immobility, and chronic venous insufficiency.

Lymphedema may also be self-induced.

Surgery and radiation: As outlined earlier, this is by far the most common cause for secondary lymphedema in the United States. Surgical procedures in cancer therapy commonly include the removal (dissection) of lymph nodes. The goal of these procedures is to eliminate the cancer cells and to save the patient’s life.

A side effect in lymph node dissection is the disruption in the lymph transport. If the remaining lymphatics are unable to manage the lymphatic load, secondary lymphedema will develop.

In the early years of breast cancer surgery radical mastectomy was the only option available for patients. Radical mastectomy includes the removal of the entire mammary gland, the axillary lymph nodes, and the pectoralis muscles under the breast. Although common in the past, radical mastectomy is now rarely performed and is recommended only if the cancer cells have spread to the muscles under the mammary gland. Modified radical mastectomy is now more commonly performed. This procedure includes the removal of the breast and part of the axillary lymph nodes. In certain forms of breast cancer, a simple or total mastectomy is performed, in which only the mammary gland, but not the axillary lymph nodes, is removed.

Today, many women with breast cancer are given the choice between mastectomy and lumpectomy. In lumpectomy, also referred to as breast-conserving surgery, only the part of the mammary gland containing the malignant tumor and some of the normal surrounding tissue are removed. Most women after breast surgery, especially after lumpectomy, receive radiation treatment (Fig. 3.3).

Sentinel lymph node biopsy, a relatively new technique, was developed to determine if cancer cells have spread to the axillary nodes and trunks, without having to perform a traditional axillary lymph node dissection during which, on average, ~10–15 axillary lymph nodes are removed. A sentinel lymph node biopsy requires the removal of only those lymph nodes to which the mammary gland drains first (sentinel nodes) before reaching the rest of the axillary lymph nodes. A pathologist then closely reviews one to three lymph nodes. If they do not contain malignant cells, the chance that the remaining axillary nodes are cancer free is ~ 95%, and removal of additional axillary nodes may be avoided.

Radiation (or radiotherapy) is the treatment of cancer and other diseases with ionizing radiation. The goal of this therapy is to destroy cancer cells that may linger after surgery. It uses either precisely aimed, high-energy, external beam radiation or radioactive seeds that are implanted in the tumor area. Malignant cells often grow at a faster rate than normal cells; this makes many cancers very sensitive; that is, vulnerable to radiation.

Although radiation damages both cancer cells and normal cells, the normal cells are able to repair themselves and continue to function properly. Radiation is usually administered 5 days a week for several weeks and may also contribute to the onset of lymphedema. Rays can cause fibrosis in the tissues, leading to an impaired lymph transport, and hinder the regeneration of lymph vessels. Radiation may also affect nervous tissue, which can result in numerous problems affecting either the lymphedema itself or the patient’s ability and compliance during the treatment of the lymphedema (radiation plexopathy; see Complications in Lymphedema later in this chapter).

Trauma: Traumatic insults involving the lymphatic system may cause a significant reduction in lymph flow, resulting in secondary lymphedema (burns, larger skin abrasions). Scar tissue hinders regeneration (lympholymphatic anastomosis) of lymph collectors, further exacerbating the problem. Post-traumatic secondary lymphedema develops from a mechanical insufficiency of the lymphatic system as a result of tissue lesions and should not be confused with post-traumatic edema. Post-traumatic edema is a local result due to trauma, which usually recedes after a few days (see Lipedema later in this chapter).

Fig. 3.3 a, b a. Secondary lymphedema of the left upper extremity. b. Secondary lymphedema of the left upper extremity following bilateral mastectomy.

Infection: Recurrent acute or chronic inflammatory processes affecting the lymphatic system may result in mechanical insufficiency. If inflammation involves lymph nodes (lymphadenitis) or collectors (lymphangitis), the walls tend to become fibrotic and the lymph fluid coagulates and obliterates the lymphatics, thus creating blockage to the lymph flow. In addition to the existing mechanical insufficiency, there is an increase in the volume of lymphatic load, resulting in combined insufficiency.

Lymph node and lymph vessel infections can be caused by bacteria (especially Streptococcus) and fungal infections. The inflammatory process affecting intra- and periarticular tissues in rheumatoid arthritis may spread to the lymphatics, presenting another cause for mechanical insufficiency (see Traumatic Edema later in this chapter).

The most common cause for inflammation of the lymphatic system and lymphedema in general is filariasis.

Lymphatic Filariasis

Lymphatic filariasis is the primary cause of lymphedema worldwide and is a painful and extremely disfiguring disease, which has been identified by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a leading cause for permanent and long-term disability in the world. It is a tropical disease, endemic in more than 80 countries in Africa, India, Southeast Asia, and South America, as well as in the Pacific islands and the Caribbean. Lymphatic filariasis is rare in the United States, and it is likely that those who contract it will have visited endemic regions.

According to the WHO, 1.3 billion individuals are at risk from the disease and over 120 million people are currently affected, with ~40 million being disfigured by lymphedema and suffering from recurrent infections and other secondary conditions.

Filariasis is caused by three types of round parasitic filarial worms with Wuchereria bancrofti being the most common type. The other types, Brugia malayi and Brugia timori are endemic to Southeast Asia.

Lymphatic filariasis is transmitted to humans by different types of mosquitos that bite while carrying infective-stage larvae. At the time of the bite, the larvae enter the wound and are deposited in the victim’s skin; from there the parasitic larvae migrate to the lymphatic system, where over a period of 6–12 months they develop into adult worms and mate. Male and female worms live together and form “nests” in the nodes and vessels of the lymphatic system. Adult worms live for a period of ~4–6 years; male worms can grow to 3–4 cm in length, whereas females can reach 8–10 cm.

The females produce millions of microscopic worms (microfilariae) during their lifetime, which circulate in the host’s bloodstream and are then again ingested by biting mosquitos. Once inside the mosquito, the microfilariae develop into infective-stage larvae, which then again are transmitted to other individuals, thus completing the transmission cycle (Fig. 3.4a).

During their lifetime inside the host’s lymphatic system, the worms cause dilation of and damage to the lymphatics, restricting the normal flow of lymph, and cause swelling, fibrosis, and infections to lymph vessels and nodes (lymphangitis, lymphadenitis).

While infection by larvae generally occurs in childhood in individuals living in endemic countries, the painful and disfiguring symptoms of this condition typically manifest themselves later in life.

Fig. 3.4 a, b

a Lifecycle of Wuchereria bancrofti. (Reprinted with permission from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.)

b A Nigerian man with elephantiasis, the most extreme form of lymphatic filariasis. (Reprinted with permission from The Carter Center/Emily Staub.)

Lymphatic filariasis may present asymptomatically with no external signs of disfigurement or infection but with acute (infections, fever, swelling) or chronic subclinical lymphatic damage. The chronic stage includes lymphedema, which can grow to monstrous proportions and may affect the extremities (most often the legs), breasts, and the external genitalia (labia, scrotum, and penis) causing pain, disability, and sexual dysfunction (Fig. 3.4b).

Lymphatic filariasis is typically diagnosed through blood tests that detect the presence of microfilariae in the blood, and antigen detection tests (ICT).

The primary treatment approach for individuals affected by lymphatic filariasis is pharmaceutical (diethylcarbamazine [DEC], albendazole, and ivermectin) and aims to eliminate adult worms and circulating microfilariae, thus interrupting the transmission cycle. Another important goal is to eliminate lymphatic filariasis as a public health problem by preventive measures involving mass drug administration covering the entire at-risk population of a country. The goal of the Global Alliance to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis (GAELF) is to stop the spread of filarial infection and to eradicate this disease through distribution of free medication. To interrupt the transmission of infection, mass drug administration should be implemented in endemic regions for a period of 4–6 years.

Foreigners visiting endemic countries are rarely infected; however, as a preventive measure mosquito bites should be avoided by sleeping under a mosquito net, using insect repellents, wearing long-sleeved shirts and long pants and refraining from being outside between dusk and dawn, when mosquitos are most active.

Lymphedema caused by lymphatic filariasis can be treated effectively with complete decongestive therapy (CDT), if available. Other measures to improve lymphedema and infections are patient education in self-care including hygiene, skin care, compression therapy, exercises and elevation of the affected extremity.

Malignant tumors: Malignant tumors may mechanically block the lymph flow by pressing against lymphatic structures from the outside (see Complications in Lymphedema later in this chapter). Malignant cells may also infiltrate the lymphatic system and proliferate in either lymph vessels (malignant lymphangiosis) or lymph nodes, thus blocking the flow of lymph (Fig. 3.5). Modified CDT protocols may be applied to address the symptoms associated with malignancies (Fig. 3.6).

Chronic venous insufficiency: Insufficient venous return results in an increase in venous blood pressure. The subsequent elevation in blood capillary pressure causes an increase in net filtrate (see Chronic Venous and Lympho-venous Insufficiency later in this chapter). In its primary function to actively prevent edema, the lymphatic system tries to compensate for the higher volume of the lymphatic load of water by the activation of its safety factor (see Chapter 2, Safety Factor of the Lymphatic System). Without initiation of adequate therapy for the venous problem, the lymphatic system may develop a mechanical insufficiency (combined insufficiency) over time, due to the constant strain (Fig. 3.7).

Immobility: If left without proper care, immobility caused by injuries to the spinal cord, stroke, or cerebral hemorrhage may eventually result in similar problems as discussed earlier (e.g., insufficient venous return with subsequent lymphatic overload).

Self-induced lymphedema: By use of a tourniquet (bandages, rubber band), some individuals produce a combination of venous and lymphatic obstruction on an extremity that produces the signs and symptoms of lymphedema. The ligature mark is usually easily identifiable just proximal to the swelling. This condition is extremely rare. If a therapist suspects self-induced lymphedema (also known as artificial lymphedema), it is recommended that he or she contact the referring physician following the evaluation (Fig. 3.8).

Table 3.5 Stages of lymphedema with typical symptoms

Stages of lymphedema | Characteristics |

• Latency stage | • No swelling |

• Lymphangiopathy (also stage 0/prestage/subclinical stage) | • Reduced transport capacity (TC) • “Normal” tissue consistency |

Stage 1 (reversible stage) | • Edema is soft (pitting) • No secondary tissue changes • Elevation reduces swelling |

Stage 2 (spontaneously irreversible stage) | • Lymphostatic fibrosis • Hardening of the tissue (no pitting) • Stemmer sign positive • Frequent infections |

Stage 3 (lymphostatic elephantiasis) | • Extreme increase in volume and tissue texture with typical skin changes (papillomas, deep skinfolds, etc.) • Stemmer sign positive |

Fig. 3.8 Self-induced lymphedema of the left lower extremity (note the ligature mark on the left knee).

Stages of Lymphedema

Currently, there is no cure or permanent remedy for lymphedema. The transport capacity in the damaged lymph vessels cannot be restored to its original level (see Chapter 2, Fig. 2.13).

If lymphedema is present, the lymphatic system is mechanically insufficient; that is, the transport capacity has fallen below the normal lymphatic load.

Although the swelling may recede somewhat during the night in some early-stage cases, lymphedema is a progressive condition. Regardless of genesis, lymphedema, in most cases, will gradually progress through its stages, if left untreated (Table 3.5).

There is no specific period of time for a patient to remain in a particular stage. For example, a patient will not necessarily be in stage 1 for 4 months and then progress to stage 2 for 6 months before moving to stage 3.

Stage 0

This stage is also known as the subclinical stage, or prestage, of lymphedema. In this stage, the transport capacity of the lymphatic system is subnormal, yet remains sufficient to manage the (normal) lymphatic load (see Fig. 3.1). This situation results in a limited functional reserve (FR) of the lymphatic system (see Chapter 2, Lymph Time Volume and Transport Capacity of the Lymphatic System).

Patients who have undergone surgery (or had trauma) involving the lymphatic system and do not experience the onset of lymphedema are said to be in a latency stage, which is a subcategory of stage 0. For example, those women who have had surgery for breast cancer (with or without lymph node dissection and radiation) and do not present with postmastectomy/lumpectomy lymphedema are considered to be in a latency stage. Again, in these cases, the TC is subnormal but still sufficient to drain the normal LL.

A condition known as lymphangiopathy presents if the TC is reduced by congenital malformations (dysplasia) of the lymphatic system. As long as the subnormal TC can manage the LL, lymphedema is not clinically present.

Patients in a prestage are “at risk” of developing lymphedema. The reduction in functional reserve results in a fragile balance between the subnormal TC and the LL. The onset of lymphedema correlates to the ability of the lymphatic system to compensate for any added stress to the system or the frequency of certain occurrences that may cause an increase in lymphatic load of water (or water and protein) in the limb at risk.

Patient information and education, especially following surgical procedures, can dramatically reduce the risk of developing lymphedema (see Chapter 5, Precautions and Lymphedema and Air Travel).

Stage 1

This stage, also known as the reversible stage, is characterized by soft-tissue pliability without any fibrotic alterations. Pitting is easily induced, and the swelling retains the indentation produced by the (thumb) pressure for some time (Fig. 3.9). In early stage 1, it is possible for the swelling to recede overnight.

With proper management in this early stage, it is possible for the patient to expect reduction of the extremity to a normal size (compared with the uninvolved limb). Without proper care, progression into stage 2 in the vast majority of cases is inevitable.

It is difficult to distinguish stage 1 lymphedema from edemas of other geneses. The clinician needs to take into account the patient’s history and whether the swelling resolves with conventional management (compression, elevation) or not (refer to Diagnosis and Evaluation of Lymphedema later in this chapter).

Stage 2

Stage 2, also known as spontaneously irreversible lymphedema, is primarily identified by tissue proliferation and subsequent fibrosis (lymphostatic fibrosis). Over time the tissue becomes more indurated, and pitting is difficult to induce. In stage 2, the Stemmer sign is positive (Fig. 3.10). A Stemmer sign is positive if the skin from the dorsum of the fingers and toes cannot be lifted, or lifted only with difficulty (compared with the uninvolved side). A positive Stemmer sign is considered accurate to diagnose lymphedema of the extremities; the absence of a Stemmer sign, however, does not exclude the presence of lymphedema (false-negative Stemmer sign).

In many cases, the volume of the swelling increases, which exacerbates the already compromised local immune defense (increased diffusion distance). Because of this, infections (cellulitis) in this stage are common.

Volume reduction can be expected if proper treatment is initiated in this stage of lymphedema. In most cases, the indurated tissue will not completely recede in the intensive phase of complete decongestive therapy (see Chapter 4). Reduction of fibrotic tissue is achieved mainly in the second phase of CDT with compression and good patient compliance (Fig. 3.11).

Fig. 3.11 Primary lymphedema of the right lower extremity before (left) and after (right) complete de-congestive therapy.

Lymphedema often stabilizes in stage 2. In those patients suffering from recurrent infections, the lymphedema may develop into stage 3, lymphostatic elephantiasis.

Stage 3 (Lymphostatic Elephantiasis)

Typical for this stage are an increase in volume of the lymphostatic edema and further progression of the tissue changes. Lymphostatic fibrosis increases in firmness, and other skin alterations, such as papillomas, cysts, and fistulas, hyperkeratosis, mycotic infections of the nails and skin, and ulcerations, develop frequently. Pitting may or may not be present. The natural skinfolds, especially on the dorsum of the wrist and ankle, deepen, and the Stemmer sign becomes more prominent. In many cases, cellulitis is recurrent (Fig. 3.12).

If lymphedema management starts in this stage, reduction can still be expected. To achieve good results, it is necessary to extend the duration of the intensive phase of complete decongestive therapy (CDT). In many cases, the intensive phase has to be repeated several times. Even extreme cases of lymphostatic elephantiasis can be reduced to a normal or near normal size with proper care and patient compliance (see Therapeutic Approach to Lymphedema later in this chapter).

Tissue changes or the progression of fibrosis remains the clinical trait to distinguish between the stages of lymphedema.

Tissue changes commonly seen in the progression of lymphedema are proliferation of connective tissue cells, production of collagen fibers, and an increase in fatty deposits and fibrotic changes (lymphostatic fibrosis). The fibrotic tissue tends to become sclerotic over time, increasing in firmness. Lymphostatic fibrosis is initially noticed at the distal end of the extremities, fingers, and toes (Fig. 3.13).

Pitting is generally more pronounced in the early stages of lymphedema and occurs if pressure is applied with the examiner’s thumb on the edematous tissue. Pitting is usually tested on the distal extremity (preferably over bony prominences) and occurs because of the displacement of fluid in the tissue caused by pressure with the flat thumb. The pitting response (indentation produced by pressure) can remain on the tested area for some time if there are minimal fibrotic skin changes present.

Table 3.6 Grading of lymphedema based on severity

Severity of lymphedema | Volume increase |

Minimal | <20% |

Moderate | 20%–40% |

Severe | >40% |

Angiosarcoma (Stewart-Treves syndrome; see also Complications in Lymphedema later in this chapter) may develop in long-lasting lymphedema, particularly in patients with stage 3 lymphedema. This type of angiosarcoma may develop in primary or secondary lymphedema and is characterized by extensive malignancy; it is highly lethal. Reliable data on the incidence of angiosarcoma in lymphedema are not available at this time.

Grading of Lymphedema Based on Severity

Extremity volume is not considered within the different stages of lymphedema. The severity of unilateral lymphedema in relation to volume can be assessed within each stage as minimal (less than 20% increase), moderate (20%–40% increase), or severe (more than 40%) increase in limb volume (Table 3.6).

Precipitating Factors for Lymphedema

For a patient “at risk,” the possible development of lymphedema depends on many factors (see Avoidance Mechanisms later in this chapter). Some patients are able to effectively compensate for a decrease in transport capacity and functional reserve by the regeneration of lymph vessels, utilizing alternative collateral circulation routes and lympho-venous anastomoses, and increasing the lymph time volume of remaining collectors. These patients may not exhibit signs or symptoms of lymphedema as long as the lymphatic system has found a way to compensate.

As discussed earlier, lymphedema may develop anytime during the course of a lifetime in primary cases. In secondary cases, the swelling may occur immediately postoperative, within a few months or a couple of years, or 20 years or more after surgery.

Based on the pathology and pathophysiology, as well as patient reports, certain triggers that cause the onset of lymphedema can be identified (for a more detailed review of precipitating factors and prevention of lymphedema, refer to Chapter 5, Precautions).

Lymphedema Risk Reduction (Venipuncture and Blood Pressure)

The surgical procedures used for individuals affected by breast cancer may be mastectomy, partial mastectomy, or lumpectomy. Along with the actual breast surgery for cancer, axillary lymph nodes are removed and/or radiated. As a result of axillary lymph node clearance, the normal lymphatic drainage from the extremity is impaired, and some patients experience the onset of lymphedema. Accumulated lymph in the edematous arm provides a rich culture medium for bacteria, which makes lymphedematous tissues extremely susceptible to infections. Simple injuries and puncture wounds can develop into local or generalized infections that may produce further lymphatic destruction and blockage. To reduce the risk of these postoperative complications, most patients are advised to not have blood pressure readings taken on, intravenous infusions in, or blood samples taken from the arm on the operated side.

Very few published data are available to document the exact risk of lymphedema from performing blood pressure readings, blood draws and injections on the affected extremity. Lack of research and normal variations in an individual’s lymphatic system (numbers or sizes of lymph nodes) make it difficult to quantify personal risk from each triggering factor.

While further research is needed, health care professionals are encouraged to minimize the risk of lymphedema by taking blood pressure readings and blood draws from and giving injections to the nonaffected limb whenever possible. In patients with breast cancer on both sides, these procedures should be performed on the leg or the foot. If this is not possible, the procedure should be carried out on the nondominant arm. If one side has had no lymph node removal, the arm on that side should be used, regardless of whether it is the dominant arm. In an emergency, however (such as a car accident), and if an intravenous line must be started, medical professionals must be allowed to do what they need to do to start the intravenous line as soon as possible.

If a port is present, blood draws should be taken directly from there. In patients with “bad” veins, good hydration and some form of heat (heat pads, warm water) help to dilate the veins prior to cannulation.

To avoid the onset of lymphedema, or infections in lymphedema, health care professionals should follow expert consensus regarding best practice to avoid lymphedema, and inform patients with breast cancer about their risk for lymphedema. Until further research is available, the National Lymphedema Network’s Position Statement on risk reduction practices should be used to deliver information to patients.

Not all medical professionals are familiar with the precautions for avoiding lymphedema, so patients have to be particularly watchful advocates for themselves. Lymphedema alert bracelets are available from The National Lymphedema Network. Wearing this bracelet increases the odds of remaining lymphedema-free and at the same time educates the medical community.

Increase in blood capillary pressure: Active hyperemia (vasodilation) that results from a local or systemic application causes an increase in blood flow, which ultimately will increase the lymphatic load of water and stress a compromised lymphatic system (see Chapter 2, Fig. 2.9). Examples of active hyperemia include local hot pack, other thermal modalities (diathermy, electrical stimulation, ultrasound), massage, vigorous exercise, and infection of the limb “at risk.” Hot tubs and saunas, hot weather and high humidity, as well as injuries, are additional triggering factors.

Passive vasodilation as a result of the obstruction of the venous return will also result in increased net filtrate and place additional stress on the compromised lymphatic system. Examples include chronic venous insufficiency, cardiac insufficiency, and immobility, as well as the examples listed under the next category.

Fluctuation in weight gain and fluid volumes: Pregnancy and obesity, excessive weight gains during the menstrual cycle (cyclic idiopathic edema), and certain medications are known to trigger the onset of lymphedema by causing additional stress (lymphatic load) on the compromised lymphatic system.

Injury: Even in subclinical stages of lymphedema, the immune response is reduced as a result of edematous saturation of the tissues on a microscopic level. Any insult to the integrity of the skin may cause infection, thus triggering the onset of lymphedema. Examples include insect bites, pet scratches, injections, intravenous cannulation, blood pressure measurements on the involved extremity, cuts, and abrasions.

Changes in pressure: The change in cabin pressure during an airline flight, coupled with inactivity, may trigger the onset of lymphedema. The reduced cabin pressure may allow more fluid into the tissue spaces. Additional inactivity allows for venous pooling, which will eventually cause an increased pressure at the blood capillary level, thereby increasing filtration and the lymphatic loads (see Chapter 5, Lymphedema and Air Travel).

Avoidance Mechanisms

In an effort to maintain fluid homeostasis, the body has the ability to respond to lymphostasis, which may prevent the manifestation of lymphedema. The following discussion will focus on the body’s compensatory mechanisms.

Safety Factor

Lymph collectors not affected by either blockage (surgery, radiation, trauma) or malformation will increase their contraction frequency and amplitude (lymphangiomotoricity) in an effort to compensate for those collectors affected by mechanical insufficiency. These compensating collectors are located in the same tributary area. The mechanisms involving the lymphatic safety factor are described in Chapter 2, Safety Factor of the Lymphatic System.

Collateral Circulation

Lymph collectors circumnavigating blocked areas may be able to avoid the onset of lymphedema by redirecting lymph fluid into areas with sufficient lymph drainage. Lymph collectors of the lateral upper arm, for example, may drain into the supraclavicular lymph nodes. This may be significant in case of axillary lymph node dissection because part of the lymph fluid may be rerouted around the axillary area into the supraclavicular nodes. The chance to avoid the manifestation of lymphedema, in this case, of the arm, is even greater if the individual’s collectors of the lateral upper arm communicate with those located in the radial forearm territory (long upper arm type; see Chapter 1, Superficial Layer). If this connection exists, lymph fluid from the forearm and upper arm would be able to bypass the blocked axillary area into the supraclavicular nodes.

Interterritorial anastomoses present another possible bypass for lymph fluid. If the normal flow of lymph within a truncal territory is interrupted by lymph node dissection, the inter-territorial anastomoses may prevent the onset of swelling in those quadrants that would normally drain into the dissected lymph node groups. The higher the number of anastomoses, as described in Chapter 1, Interterritorial Anastomoses, the better the chance of avoiding lymphedema.

Lympho-Lymphatic Anastomosis

Severed lymph collectors tend to reconnect after a relatively short time (2–3 weeks). Newly formed lymph vessels reconnect the distal with the proximal lymph vessels’ stump (Fig. 3.14). Scar tissue may prevent lympho-lymphatic anastomoses. Lymph collectors separated due to blunt trauma (no skin breakage) will regenerate more effectively than collectors disconnected by incisional trauma.

Fig. 3.14a–d Reconnection of lymph collectors following blunt trauma. a Severed lymph collectors. b Intralymphatic pressure in the distal lymph collector stump increases. c Newly formed lymph vessels connecting the distal and proximal lymph vessel stumps. d Lympho-lymphatic regeneration.

Lympho-Venous Anastomosis

The distal end of a severed lymph collector may connect with an adjacent vein, creating a natural shunt. Lymph fluid then directly voids into venous blood.

Lymph Vessels in the Adventitia of Blood Vessels

Larger blood vessels have their own nutrient blood vessels (vasa vasorum vessels), which supply the wall of the larger arteries and veins with oxygen and nutrients.

There are also lymph vessels in the adventitia of larger blood vessels (lymph vasa vasorum). With lymphedema present, lymphatic loads may reach these lymph vasa vasorum vessels via tissue channels. Lymph vessels in the adventitia of blood vessels have the ability to increase their activity, thus providing an additional drainage pathway for stagnant lymph fluid.

Macrophages

If protein-rich fluid accumulates in the tissues, monocytes leave the blood capillaries in large numbers. Once in the tissues, they are macrophages (phagocytes) and will digest accumulated protein molecules. The subsequent decrease in tissue protein concentration will result in an increased reabsorption and a decrease in net filtrate, which will help to reduce the lymphatic loads. The digested protein molecules are broken down into amino acids, which do not present a lymphatic load, and are removed by the blood circulatory system.

Complications in Lymphedema

Lymphedema is often combined with other pathologies and conditions, which either aggravate the existing symptoms or present additional complicating factors in the treatment of lymphedema.

The following is a list of the most common complications.

Reflux: Retrograde flow of lymph fluid caused by valvular insufficiency of lymph collectors. Valvular insufficiency is the result of hyperplasia, dilation of collectors due to constant strain or blockage of lymph flow, or organic changes in the walls of lymph collectors (mural insufficiency; see Chapter 2, Mechanical Insufficiency).

If valvular insufficiency is present, lymph fluid is propelled not only to proximal but also to distal (retrograde flow) during the contraction of lymph angions. Reflux presents as blisterlike formations (lymphatic cysts) on the surface of the skin, commonly in the axillary (Fig. 3.15), cubital, genital (see Chapter 5, Fig. 5.25), and popliteal areas. Lymphatic cysts contain lymph fluid, which may be clear or chylous. If chylous, the reflux originates from the intestinal lymph system.

Clinical relevance: Lymphatic cysts may easily break open, presenting an entryway for pathogens, which can cause infection. Burst cysts associated with leaking of lymph fluid (lymphorrhea) are termed lymphatic fistulas.

To avoid damage to cysts and to prevent infection, it is recommended to cover the cyst with sterile gauze during treatment (local antibiotics should be applied around the fistulas), and not manually work on or around the cysts and fistulas. Cysts should be padded with soft foam material (donut or U-shaped padding) to avoid direct contact with the bandage materials while the patient wears the bandages.

Radiation fibrosis: Reaction of the skin to irradiation, leaving visible and/or palpable changes in the skin and subcutaneous tissue. The skin in radiation fibrosis appears reddish brown (Fig. 3.16), and superficial blood vessels may be dilated in the irradiated area (telangiectasia) (Fig. 3.17). The newly formed scar tissue may be soft or hard, and the skin may adhere to the underlying fascia.

Clinical relevance: The tissue changes in radiation fibrosis tend to get worse over time, possibly resulting in compression of venous blood vessels and subsequent dilation of superficial veins.

Radiation fibrosis may cause pain, limitations in range of motion if near a joint, paresthesia, pareses, and paralysis, which can occur even years after the radiation therapy was administered.

The skin in radiation fibrosis may also be more fragile. To avoid mechanical damage to the irradiated skin, CDT presents a local contraindication in radiation fibrosis if there is adhesion to the fascia or if the radiated area is painful. Movements designed to mildly stretch the affected skin area should be incorporated into the exercise program. CDT techniques may be applied with lighter pressures if skin discoloration or telangiectasia and/or dilated superficial veins are present and the skin is pliable.

Infection: Bacterial (especially Streptococcus) and fungal infections are common in patients with lymphedema (especially stages 2 and 3). Clinical symptoms of cellulitis are fever and tenderness; the skin is red with indistinct margins (Fig. 3.18).

Fungal infections may involve the skin and/or nails and most often affect the lower extremities (Fig. 3.19). Nails generally take on a yellow color, split, flake, and grow too thick. Symptoms in fungal infections of the skin include itching, crusting, scaling, and maceration between the toes. The skin may be moist or dry and may show a grayish-white film. A sweet odor is often associated with fungal infections.

Clinical relevance: Episodes of cellulitis (or erysipelas) usually require a course of systemic antibiotics. CDT is generally contraindicated until the infection has cleared. Therapy for the fungal infection with local or systemic antifungal medication precedes lymphedema treatment.

Hyperkeratosis: Hypertrophy of the corneous layer of the skin. This condition is often associated with lymphedema, especially on the lower extremity. Wartlike papillomas are generally observed on the feet and toes. Skinfolds may be deepened.

Clinical relevance: Good skin hygiene is necessary to avoid possible infections in the moist skinfolds. Hyperkeratosis may be treated with over-the-counter medication or, in extreme cases, may be surgically removed (after decongestion), especially if papillomas interfere with the donning of compression garments. Because papillomas are elevated nodules, care must be taken to not tear the papillomas while donning the garments.

Scars: Scars located perpendicular to lymph collectors may present a blockage to lymph drainage, especially if the scar tissue adheres to the underlying tissues and/or exceeds 3 mm in width.

Clinical relevance: The treatment of fresh scars is covered later in this chapter under Traumatic Edema. Older scars causing discomfort, blocking lymph flow, or hindering exercise protocols may be treated with techniques and materials designed to soften the indurated tissue (foam, manual techniques, nonthermal ultrasound).

Malignancies: Blockage of the lymphatic return may be caused by malignant tumors, in which case the swelling would be categorized as malignant lymphedema. As described previously in this chapter, a rare form of malignancy may develop as a result of long-standing lymphedema (angiosarcoma or Stewart-Treves syndrome). Malignant cells may also infiltrate the lymphatic system, causing blockage to the lymph flow (malignant lymphangiosis) (Fig. 3.20).

Signs and symptoms of malignancies include sudden onset and fast progression of the swelling, pain (especially in the swollen extremity), paresthesia, paresis and paralysis, enlarged lymph nodes, ulcerations on the skin, varicose veins on the thorax, and elevated shoulder due to pain on the involved side in upper extremity involvement (Fig. 3.21).

Changes in the color and integrity of the skin may also indicate malignancies: cellulitis-like redness is often associated with malignant lymphangiosis (Fig. 3.20) (the redness does not appear suddenly as in cellulitis but develops slowly over the course of weeks and months). Hematoma-like discolorations on the skin may indicate the presence of angiosarcoma.

Clinical relevance: If any of the above symptoms are present, if lymphedema is therapy-resistant, or if there is a sudden relapse in swelling in previously treated lymphedema, a physician must be consulted immediately. Modified CDT protocols may be applied to reduce and alleviate the symptoms associated with malignancies (palliative care).

Paresis and paralysis: Partial or complete loss of motor function may be caused by injuries to peripheral nerves, the spinal cord, stroke or cerebral hemorrhage, infiltration of nervous tissue by malignant tumors, or radiation (radiation plexopathy).

Genital swelling: Frequently present in combination with lower extremity lymphedema. In 40%–60% of the male lymphedema population, the external genitalia (scrotum and/or penis) may also present with significant swelling, in addition to the lower extremity involvement. Females are affected less frequently.

Clinical relevance: These patients should be thoroughly instructed in self-management issues (e.g., hygiene, the application of bandages or pads to the swollen area, appropriate clothing, etc.). It is important that compression garments incorporate the genital swelling (pantyhose, compressive body parts; refer to the appropriate sections in Chapters 4 and 5).

Other pathologies combined with lymphedema: Lymphedema is often combined with other conditions and pathologies that may worsen the symptoms associated with lymphedema or complicate the treatment protocol with additional obstacles.

Clinical relevance: It is necessary to incorporate modifications in the treatment protocol for lymphedema to appropriately address signs and symptoms associated with any additional pathologies.

Examples

Lymphedema and cardiac insufficiency. Abdominal techniques are contraindicated; the affected extremity (especially in leg lymphedema) should be treated only in sections to avoid too much venous blood and lymph fluid returning to the heart during the treatment. Lighter compression is necessary for the same reason.

Lymphedema and obesity. Obesity contributes to the onset of lymphedema and often worsens the symptoms of existing lymphedema (see p. 309). In a 2008 study conducted by researchers at the University of Missouri-Columbia, it was suggested that the risk of developing upper extremity lymphedema following breast cancer surgery was 40%–60% higher in women with a body mass index (BMI) classified as overweight or obese, compared with women of normal weight. In their study, which included 193 breast cancer survivors, researchers also reported that the risk of lymphedema is especially high in over-weight or obese women who undergo cancer treatment involving the dominant side, or who experience postoperative swelling.

Excessive weight and obesity may also contribute to the onset of primary and secondary lymphedema involving the lower extremities. Excessive weight, especially morbid obesity, can have a negative impact on the return of lymphatic fluid from the legs; additional fluid volumes associated with obesity may overwhelm an already impaired lymphatic system. Direct pressure on lymphatic vessels by excess fatty tissue, impaired diaphragmatic breathing and decreased muscular function can also be factors contributing to the manifestation of lymphedema. Chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) is often associated with obesity. The increased burden on the lymphatic system in CVI can play a significant role in the manifestation of lower extremity lymphedema.

The progress of treatment of existing lymphedema may be seriously hampered in patients with a high BMI. With obese patients it is often difficult to apply bandages, especially in cases of lymphedema affecting the lower extremities. Furthermore, the compressive materials (bandages, garments) applied to the affected extremities have a tendency to slide in obese patients. Compression garments may have to be custom made, creating an additional financial burden on the patient.

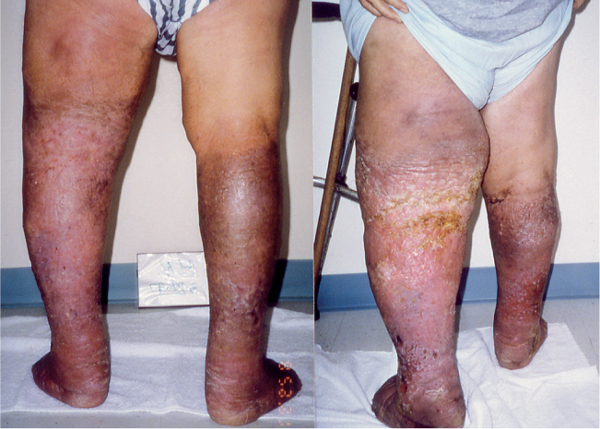

Fig. 3.22 Lymphedema in combination with venous insufficiency (stage 3), ulcerations, and lymphorrhea on both lower extremities before (right) and after (left) complete decongestive therapy.

Exercise—a very important aspect of the management of lymphedema—may be made difficult as well. Mobility problems associated with a high body mass index can affect the patient’s participation in treatment, and exercise protocols used in lymphedema therapy for the upper and lower extremities may have to be modified accordingly.

Weight management and proper nutrition are essential for successful long-term lymphedema management (see also Nutritional Aspects in Lymphedema later in this chapter).

Lymphedema and orthopedic problems. Symptoms associated with lymphedema and orthopedic pathologies will magnify each other and may even exacerbate the current presentation of either or both pathologies. Relevant combinations are “frozen” shoulder and upper extremity lymphedema or hip/knee problems associated with lymphedema of the leg. To interrupt the vicious cycle, it is necessary to address all involved pathologies. It is often advised to prioritize treatment according to the more limiting factors found during the assessment.

Lymphedema and venous insufficiency. Venous insufficiency contributes to the onset of lymphedema and worsens symptoms of existing lower extremity lymphedema (see Chronic Venous and Lympho-venous Insufficiency later in this chapter). The additional presence of venous ulcerations necessitates proper wound care (Fig. 3.22; see also Wounds and Skin Lesions later in this chapter). It is recommended that the lymphedema therapist incorporate the materials prescribed by the physician into the compression bandage.

Although venous insufficiency will benefit from CDT for lower extremity lymphedema, it is imperative to observe possible complications associated with venous insufficiency (thrombophlebitis). These complications may present a contraindication for the treatment of lymphedema.

Lymphedema and diabetes. Diabetes is often associated with dry skin, frequent infections, neuropathy, slowhealing wounds, and high blood pressure. To address these problems, the treatment protocol for lymphedema may be modified accordingly, with more emphasis on skin hygiene. If ulcerations are present, the incorporation of wound care into the protocol becomes necessary. As with venous ulcers, it is recommended that the lymphedema therapist use and incorporate the materials prescribed by the physician into the compression bandage.

Axillary Web Syndrome

Definition

Axillary web syndrome (AWS) is a condition that may develop after interruption to the axillary lymphatics such as axillary lymph node dissection, sentinel lymph node dissection, trauma, or an obstruction from cancer. It is a visible and palpable web of tissue that becomes taut with shoulder abduction. It is located in the axilla region and often extends distally along the anterior, medial upper arm toward the antecubital space and may extend as far as the base of the thumb. In patients with a thin body type, it may also extend proximally along the lateral chest wall (Fig. 3.23a). In a few cases, subcutaneous nodules have also been reported along the cord. It has the appearance of a tight cord of tissue being stretched underneath the skin (Fig. 3.23b) and is sometimes referred to as “cording.” Other terms used to describe AWS include Mondor’s disease, lymphatic cording, subcutaneous fibrous banding, fiddle-string phenomenon, lymph vessel fibrosis, lymphangiofibrosis thrombotica occlusiva, and lymph thrombosis. AWS is painful and can limit range of movement (ROM) of the shoulder, elbow, wrist and trunk. The cord tends to be more extensive in patients who have had axillary lymph node dissection compared with those who have had sentinel lymph node dissection. AWS should not be analogous with soft-tissue tightness, because many patients have soft-tissue tightness following axillary lymph node dissection but do not have AWS.

Fig. 3.23a, b

a Location of the axillary web syndrome.

b Axillary web syndrome of the left arm (multiple cords visible in the antecubital space).

AWS appears to develop more often in patients who have a thin body type. It is suggested the cord may be more difficult to detect in heavier-set patients because the thick layer of subcutaneous tissue may cover the cord. The subcutaneous fat tissue may also make it more difficult for the skin to adhere to the underlying tissue caused by the cord.

Physiology/Pathophysiology

It has been indicated that AWS is a variant of Mondor’s syndrome. Mondor’s syndrome is caused by a thrombosed superficial vein and presents as a cord on the chest wall, which is painful, tender, and causes skin retraction and pulling. AWS development is thought to be caused by an injury to the axillary lymphatics following axillary lymph node dissection, trauma, or an obstruction from cancer. An interruption of the lympho-venous channels causes a thrombosis and stagnation of the lympho-venous fluid, resulting in inflammation, fibrosis, and shortening of the tissue. Tissue biopsies of the cord taken from a small number of patients have indicated dilated lymphatics, a fibrin clot in the lymphatics, and venous thrombosis.

The reported incidence of AWS is variable ranging from 6%–72%. There are indications that AWS primarily occurs in the early postoperative period beginning ~1–5 weeks following surgery and resolves on its own within 2–3 months. Although its occurrence is most often seen in the acute stages following surgery, AWS has been reported to develop months or years after surgery. Lingering remnants of the AWS cord have also been observed beyond the 3-month timeframe following surgery.

Evaluation

Because there is postoperative delay in the development of AWS, the patient will typically have fairly normal ROM following surgery. Within a few weeks, the patient starts to experience tightening and pain in the arm which begins to limit ROM. The patient may come to the clinic with the affected arm in a protected position of shoulder protraction, internal rotation, elbow flexion, with wrist flexed and supinated because it is painful to let the arm rest by the side. Shoulder abduction is the most limited movement in most cases, but elbow extension is also often limited especially with arm abduction. The cord is taut and painful with palpation.

With a severe cord that extends to the elbow or base of the thumb, the cord will be easily detected by the attempt to position the arm at the side. The patient will not be able to extend the elbow or wrist fully and a cord can be visible and palpable in the forearm. If the cord is located in the axilla, the cord will become visible when the arm is abducted and a stretch is applied to the cord. In thin patients, a cord may be visible on the lateral chest wall at the end range of shoulder abduction and trunk sidebending. Some patients will report tension in the lateral chest wall similar to the cording symptoms felt in the arm and axilla even though a cord may not be observed. The reason the cord may not be visible in this area may be due to the presence of subcutaneous fatty tissue. A thorough assessment of all affected areas is indicated so that fragments of the cord are not missed.

Therapeutic Approach

From a therapist’s perspective, any indication of AWS should not be ignored. Treatment of AWS can rapidly reduce the pain caused by the tension of the cord and dramatically improve ROM and function. Without treatment, AWS could cause prolonged shoulder immobility which could lead to secondary problems such as altered movement patterns, poor posture, malalignment, muscle imbalance, impingement, frozen shoulder, soft-tissue tightness, and chronic pain.

An effective manual technique used to treat AWS is skin traction starting at the most distal portion of the cord and working proximally. It involves a gentle stretch on the superficial tissue over the cord. Using the palmar surface of the fingers, both hands are placed ~2–10 cm apart along the cord and a stretch is applied along the direction of the cord in the opposite direction. (Fig. 3.24). Once the patient no longer feels tension in the area, the arm is repositioned into further abduction to apply more tension on the cord. Feedback from the patient is imperative throughout treatment as the cord may become tight in another area as one area is relieved. Work the area of the cord where the patient indicates tightness. The elbow should stay extended throughout the progression into abduction. Wrist extension can also be applied to achieve tension on the cord.

Cord bending is another manual technique used to treat AWS. While the cord is tensed when the patient is positioned in a stretch, a perpendicular pressure is applied on the cord with the thumbs while bending the tissue in the opposite direction with the other fingers. Cord bending should be applied to the area of the cord where the patient indicates tightness. This technique can also be used in the pectoral region to stretch the tissue (Fig. 3.25).

The cords may break or release during treatment and a palpable and sometimes audible pop can be experienced. No adverse effects have been reported following the breaking of the cords though it is important to be cautious and avoid being overly aggressive in trying to break the cords until further research is obtained on the exact mechanics of the cord breaking. It is not known whether the noise is due to the actual cord or the supporting fibrous tissue around the cord breaking, or to another cause. If a cord does break, an immediate increase in ROM is experienced. To reduce anxiety, it is beneficial to explain to the patient that the cord may break and that he or she may hear and feel the cord release during treatment and to reassure him or her that this is a normal response. Gentle manual techniques are quite effective in helping resolve the cords without being overly aggressive.

If the cord extends into the arm, a gentle but effective approach to the rapid resolution of the cord is the short-term use of gradient compression bandaging. The application of low-stretch compression bandages achieving a gradient compression can be used for 1–3 days. Less compression is needed compared with regular lymphedema compression bandaging, therefore 2–3 compression bandages with appropriate padding are usually sufficient. If there is lymphedema involvement, the appropriate compression to treat the lymphedema is indicated. Like all bandaging, close monitoring and patient education is necessary to avoid complications. A compression garment is not as effective in resolving the cord.

Instruction in a home exercise program is dependent on the location and severity of the cord. Gentle ROM exercises should be initiated at the most distal portion of the cord first. A cord that extends to the base of the thumb can be quite painful; therefore thumb and wrist extension in addition to elbow extension may be all the patient can tolerate initially. Proximal ROM exercises (such as pendulum exercises and/or the finger walk on the wall) can be added as the cord resolves distally. The patient can be instructed in a self-skin stretch, similar to a nerve stretch, by placing the affected hand on the wall with the wrist extended, forearm supinated, elbow extended, arm abducted below 90 degrees and scapula depressed. The palmar surface of the unaffected hand can be used to apply a gentle proximal stretch on the cord (Fig. 3.26). This self skin-stretch of the cord can also be applied with more advanced stretches such as pectoralis and lattisimus dorsi stretches or other exercises indicated by therapist. A caregiver can also be instructed in manual techniques to stretch the cord to help increase the ROM.

It is important to focus on postural education throughout treatment. Myofascial release, craniosacral techniques, scar mobilization, joint mobilization, nerve glides, and strengthening can also be incorporated into the treatment as indicated by the therapist. Nonsteroid anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) and opioids may also be beneficial for pain management related to AWS.

Impact of Lymphedema on Quality of Life

Lymphedema affects psychological well-being and quality of life of people of all ages,16 cultures,17,18 and genders.19 Although the majority of research has been done in the area of breast cancer-related lymphedema3,20 and the highest proportion of patients living with lymphedema in the developed world may be survivors of breast cancer,21 studies show that patients suffering from either primary or secondary lymphedema experience a negative impact on their quality of life from this chronic disease.16,19,20,22–24

The association of quality of life and lymphedema has long been a concern, with research dating back over three decades.16,25,26 Primary lymphedema is reported to affect 1.15/100 000 people under 20 years of age.16 As far back as 1985, Smeltzer et al.16 reported findings from a longitudinal study at the Mayo Clinic of children and adolescents with primary lymphedema that led to recommendations that adolescents, in particular, be referred for psychological counseling.

A decade later, noting the absence of a validated tool for assessing quality of life among patients living with lymphedema, despite the general clinical awareness of such a problem, Augustin et al.19 developed and validated a tool for assessment of quality of life in lymphedema. They found that patients with primary and secondary lymphedema showed marked impairment in quality of life in all areas assessed (e.g., physical status, everyday life, social life, emotional well-being, treatment, satisfaction, and profession/household), compared with patients with early-stage venous insufficiency, and comparable reductions in quality of life compared with patients with venous leg ulcers.

In an area of greater investigation, researchers reporting quality of life outcomes among breast cancer survivors with lymphedema detail impairments in both physical and psychological aspects of life.27 For example, McWayne and Heiney28 and Collins et al.29 reported that psychological problems (e.g., frustration, distress, depression, and anxiety) are associated with the presence of lymphedema among breast cancer survivors. In addition, lymphedema may compromise the normal activities of daily living (e.g., sleeping, driving, carrying items, household chores, occupational responsibilities, dressing, or gardening and other leisure activities),30–33 domestic role,35 and family responsibilities.32 Survivors with lymphedema experience more symptoms (increase in arm and shoulder size; tighter fitting clothing, sleeve cuff, and jewelry; limited elbow function; arm/hand weakness; loss of sleep secondary to arm discomfort; tenderness; swelling; pitting; blistering; firmness/tightness; heaviness; stiffness; aching; breast swelling) than those survivors without lymphedema.22–24,35 While breast cancer survivors report that they are most fearful of a cancer recurrence, it is noted that their second greatest fear is that they will develop lymphedema.36,37

Konecne and Perdomo38 reported that lymphedema could lead to functional limitations for elderly individuals (e.g., decreased ability to reach, lift, push, pull, twist, carry, shove, and grasp), which in turn could affect their quality of life. As people living with primary and secondary lymphedema grow older, the impact on quality of life may burgeon.39

This chapter focuses on the personal impact on quality of life when living with lymphedema based on qualitative studies of individuals and families and the objective impact on quality of life in areas such as function and finances. Personal quotations (Armer, unpublished data) and studies that are selected for review22,40 reveal the universal and widespread impact of this chronic condition.

Personal Views of Lymphedema across the Globe

It’s like giving birth. Everybody can tell you it feels like this and this, but until you experience it yourself, you don’t know…

If you’ve got children and you’ve got a husband, you’ve got to be up. There’s no time to be sick… It does influence relationships, especially with your husband… My husband likes a good looking woman with breasts and a nice body and everything. So it has been hard work for me to, to survive this whole thing…

I think at first… you try to have a lot of hope that this thing… is a temporary sort of situation. And I think that, um, the disappointment, with time and as you realize it’s not going to go away, something that you have to cope with for the rest of your life, so it is a disappointment.”–V, breast cancer survivor and professional business woman, living with lymphedema, South Africa Since going through breast cancer 5 years ago and developing a swollen arm my doctor says [it] will only get bigger… caring for my family has been very difficult…

I fight cancer, through my weakness and through my struggle… I struggle…

Sacrifice… I am a humble person. I am grateful for everything, everyday. I am grateful…

There are other times when I think about my thick arm because of the weight of the arm. But then I have to put it out of my head… there are other things to worry about, a decent place to live, running water…” – E, breast cancer survivor and hourly domestic worker, living with lymphedema, South Africa

“Going through treatment for breast cancer (41 years ago) was nothing compared to all these (39) years with lymphedema.” – R, breast cancer survivor and retired secretary, living with lymphedema, Midwestern United States

These quotations reveal the personal dimensions of living with lymphedema following breast cancer treatment in two very disparate parts of the world, with comments resonating with the impact on quality of life among individuals of vastly different ages and cultures. It is important that health professionals hear the voices of the individuals they treat who are living with the challenges of lymphedema.

Impact of Minimal Limb Volume Change on Quality of Life among Survivors with Lymphedema