Fig. 33.1

Decision tree for the diagnosis and workup of hypoglycemic disorders

Seventy-Two Hour Fast

The 72-h fast is prolonged withholding of food and caloric fluids until Whipple’s triad has been documented. This should be undertaken by a center that is experienced in performing the test. The fast can be initiated as an outpatient as 35 % of patients have a positive fast in the first 12 h. Those that have a negative study can be admitted to complete the fast. In a group of 170 insulinoma patients, 93 % had a positive fast by 48 h of fasting and 99 % by 72 h [15].

Criteria for ending the fast:

1.

Documentation of Whipple’s triad

2.

Serum glucose <55 mg/dl with previous documentation of Whipple’s triad

3.

Progressive increase in beta hydroxybutyrate

4.

At 72 h if no symptoms or severely depressed glucose level occurs

Ending the fast may be a difficult, especially in the setting of nonspecific symptoms with low normal serum glucose near the hypoglycemic threshold. Confounding this difficulty is the fact that low serum glucose may be physiological, and glucose levels in the 40–50 mg/dl range are not uncommonly seen, particularly in young lean women. A detailed history should be taken from the patient at the time of the symptoms to establish whether neuroglycopenia is occurring. Tests can include those of cognitive function, for example serial 7 s. Frequent reevaluation may be needed, including the need for bedside glucose testing if laboratory values are delayed.

Criteria for Hyperinsulinemia

1.

Plasma insulin concentrations ≥3 μU/ml

2.

C-peptide ≥ to 200 pmol/l

3.

Proinsulin ≥ to 5 pmol/l

4.

Beta hydroxybutyrate <2.7 mmol/l. Hyperinsulinemia leads to a persistent suppression of beta hydroxybutyrate. A negative fast is suggestive if the beta hydroxybutyrate level is >2.7 mmol/l or if two consecutive values 6 h apart exceed the value at 18 h of the fast [38].

5.

Response to glucagon. In patients with hyperinsulinemia, glycogen stores are sufficient; therefore a generous serum glucose response should occur in response to glucagon. An increment of 25 mg/dl from the terminal fasting glucose should be seen in patients with hyperinsulinemia.

6.

Measurement of sulfonylureas and meglitinides using liquid chromatographic tandem mass spectrography. The evaluation will otherwise appear identical to an insulinoma.

7.

Absence of insulin antibodies.

The interpretation of insulin, C-peptide, and proinsulin concentrations during the prolonged supervised fast depends on the concomitant plasma glucose concentration. The normal overnight fasting ranges for these polypeptides do not apply when the plasma glucose is 50–55 mg/dl or lower.

Mixed Meal

Standards have not been established for the mixed meal study. The study is performed in patients with symptoms of postprandial hypoglycemia. The test is performed over 5 h after the patient ingests a meal that typically produces the symptoms. A positive result includes symptoms suggestive of neuroglycopenia in the setting of a glucose ≤50 mg/dl. It is important to note that a positive test does not provide a diagnosis, rather confirmation of Whipple’s triad in the postprandial state. If insulinoma is still suspected in a patient with positive mixed meal study, the 72-h fast may be performed. If the 72-h fast is negative, NIPHS should be suspected [16].

Selective Arterial Calcium Stimulation

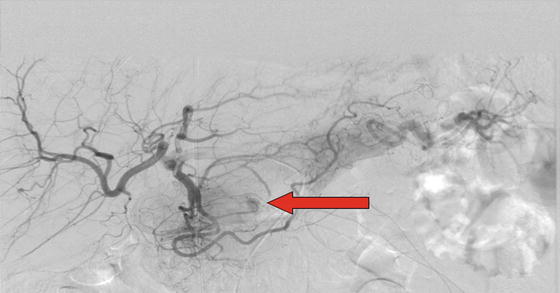

Selective arterial calcium stimulation may be used as both a diagnostic and localization test. It is indicated in patients suspected of having an insulinoma with absence of lesion or multiple lesions on imaging, or hypoglycemia secondary to NIPHS. This technique is highly sensitive, previously reported at 96 % [39]; but maybe dependent on operator experience. The procedure includes puncture of the femoral vein with catheterization of the right hepatic vein via the inferior vena cava. Calcium gluconate is selectively injected into the gastroduodenal artery, superior mesenteric artery, and splenic artery. A rise in hepatic vein insulin two- to threefold at 20, 40, and 60 s after injection of calcium will localize the excess insulin secretion to head of the pancreas (gastroduodenal artery), the uncinate (superior mesenteric artery), and the body or tail (splenic artery) (Fig. 33.2 and Table 33.1 showing arteriogram and corresponding venous insulin levels in a 53-year-old female with hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia).

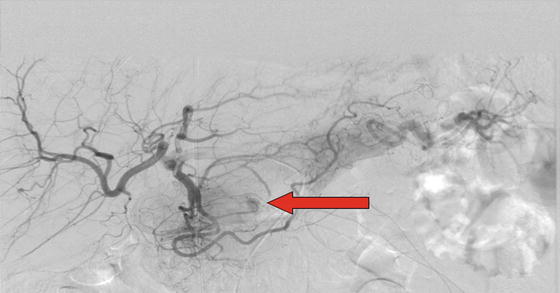

Fig. 33.2

A 53-year-old female with hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia. Arteriogram after calcium gluconate infusion into the superior mesenteric artery, gastroduodenal artery, and splenic artery reveals a vascular “blush” in the gastroduodenal artery

Table 33.1

Calcium stimulated hepatic venous sampling showing a sixfold increase in venous insulin levels in the arterial domain of the gastroduodenal artery at 40 s, corresponding to the abnormal arteriogram

Venous insulin (mcIU/ml) | Superior mesenteric artery | Gastroduodenal artery | Splenic artery |

|---|---|---|---|

Systemic insulin | 20.1 | 9.7 | 7.3 |

Hepatic (baseline) | 14 | 10 | 7.7 |

Insulin 20 s | 13.8 | 30.7 | 8.2 |

Insulin 40 s | 15.5 | 64.6 | 8.5 |

Insulin 60 s | 12.7 | 44 | 7.8 |

Selective arterial calcium stimulation test may be used as a diagnostic tool in patients with renal failure, when beta cell polypeptides are unreliable [40].

Localization

Once hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia is confirmed, the next step is to localize the lesion. Imaging techniques are successful in locating insulinomas for majority of cases due to the hypervascularity of the lesions. Imaging not only localizes the primary tumor, it also allows for evaluation of metastatic lesions. Localization is important as it will prevent morbidity associated with extensive abdominal explorations and possible need for repeat surgeries. Surgical cure may depend on accurate localization of the tumor.

Transabdominal ultrasonography (TUS), endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), intraoperative ultrasound (IOUS), computed tomography (CT), and arteriography have been used. Decision about which study to perform will depend on center experience and expertise.

Noninvasive Techniques

The advantage of noninvasive techniques is lower expense and fewer complications. TUS has a sensitivity of 9–67 % and CT scan 71–82 % [41, 42]. Large body habitus may reduce sensitivity. Imaging characteristics of CT typically involve enhancing, vascular lesions visualized during both arterial and portal venous phases, although smaller lesions are better seen during the arterial phase (Figs. 33.3 and 33.4). Lesions do not classically alter of the natural contour of the pancreas. The presence of calcification is usually a sign of malignancy as well as invasion and necrosis [41].

Fig. 33.3

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the abdomen including triphasic imaging through the pancreas of a 38-year-old male with hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia. A subtle, rounded, 1.8-cm nodule in the neck of the pancreas slightly enhances on the late arterial phase, concerning for an insulinoma

Fig. 33.4

A 48-year-old female with hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the abdomen including triphasic imaging through the pancreas reveals a 7-mm nodule in the posterior tail of the pancreas, concerning for an insulinoma

Invasive Techniques

EUS has a reported sensitivity greater than 90 % [43, 44] and is indicated if localization fails by noninvasive techniques. Intraoperative ultrasound has a sensitivity of 75–100 % if performed by experienced providers and is particularly helpful in detecting lesions in MEN 1. Both techniques are useful in mapping anatomy with respect to the pancreatic duct and blood vessels [45]. Arteriography is now only limited to the selective arterial calcium stimulation test in our practice.

Treatment

Insulinomas

Localization and resection is the treatment of choice, preserving both endocrine and exocrine function if possible. Successful removal of the insulinoma will lead to a normal life expectancy for the patient. Very deep lesions may require segmental resection, but solitary, superficial lesions may only require enucleation. More extensive resection is required if there is concern for malignancy. Insulinomas associated with MEN 1 may require a distal subtotal pancreatectomy for lesions in the body or tail of the pancreas. Lesions in the head of the pancreas can either be enucleated or treated with ethanol injection which will be discussed below.

NIPHS

NIPHS is initially treated with dietary and medical therapy. If patients continue to have intolerable symptoms despite these measures, surgical resection is indicated. This involves localization of the region of beta cell hyperfunction by selective arterial calcium stimulation. Although thought to be a diffuse process, insulin response to calcium injection often localizes to one arterial domain. Once identified, partial pancreatectomy is recommended.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree