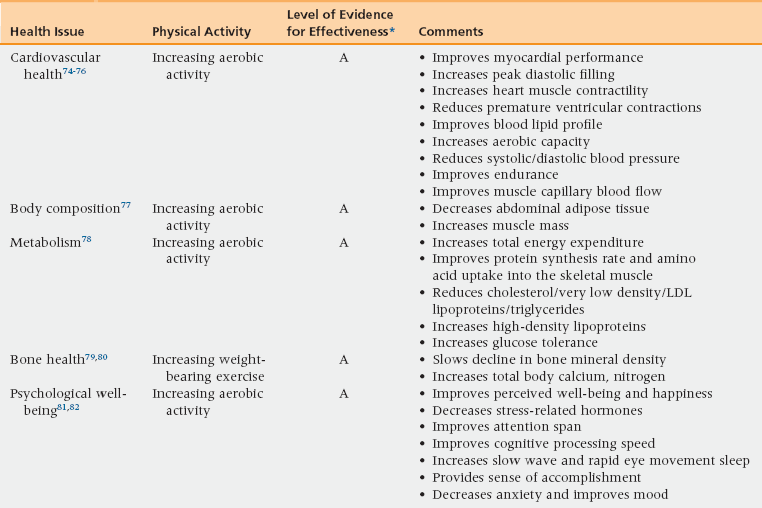

4 Essentials of Health Promotion for Aging Adults Guidelines for Screening before Exercise Maintaining Optimal Nutritional Intake Putting Prevention into Practice Facilitators for Implementation of Prevention Practices Motivating Patients to Engage in Health Promotion Activities: The Seven-Step Approach Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Define the purpose of health promotion and disease prevention in older adults. • Describe an appropriate immunization schedule for older adults. • Describe three lifestyle modifications that can prevent disease. • Describe the relevant relationship between nutrition and nutritional status and health. • Delineate the use of prophylactic medication on cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, and cancer prevention. • State appropriate cancer screening guidelines for older adults. • Plan strategies for putting prevention into practice by identifying facilitators and motivational techniques. Health promotion is the science and art of helping people change their lifestyle to move toward a state of optimal health, defined as a balance of physical, emotional, social, spiritual, and intellectual health.1 The purpose of health promotion and disease prevention is to reduce the potential years of life lost in premature mortality and to ensure better quality of remaining life. It is the latter focus that is noted to be critically important for older adults. Health promotion activities include the use of immunizations to prevent the occurrence of acute problems such as influenza and pneumonia, risk factor reduction through lifestyle modifications such as smoking cessation or regular physical activity, and the prophylactic use of medication to prevent cardiovascular disease or prevent musculoskeletal disorders. In addition, health promotion includes screening to facilitate the early identification of disease so that reatment can be initiated. Most important among these is the screening for malignancies. There are multiple guidelines for health promotion activities available for clinicians as well as patient-specific information to help individuals decide what type of health promotion activities they want to engage in. The decisions about whether or not to adhere to these guidelines are often difficult for the older individual or the individual with health care power of attorney (or proxy) to make. Guidelines for overall health screening decisions2 can help direct clinicians and the patient or their proxy in this decision process. An individualized approach is critical when working with older individuals in the area of health promotion and should drive the decision process. Table 4-1 provides an overview of recommendations for immunizations for older adults. The U.S. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices and the Centers for Disease Control currently recommend that all older adults be immunized against influenza annually and that they receive at least one pneumococcal vaccination.2,3 All older adults 65 years of age and older should receive an additional pneumococcal vaccination 5 years or more after their first immunization, if they were vaccinated with PPSV23 before the age of 65. The Food and Drug Administration has approved the zoster vaccine for use in persons age 50 and above; however, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices continues to recommend that vaccination begin at age 60.3 Compliance with recommended immunization guidelines has improved, although the goal set in Healthy People 2010 of 95% adherence to immunization has not been met and adult adherence rates continue to lag behind those seen in children.4 To facilitate compliance the federal government in 2002 approved standing orders for annual influenza vaccinations and pneumococcal pneumonia vaccination for older adults in institutional settings and home health agencies for all Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries. Medicare health coverage (Part B) will cover vaccines to prevent influenza and pneumonia and hepatitis B if the patient is at medium to high risk for this disease. No copay is associated with these vaccines. All vaccines, other than those for flu, pneumonia, or hepatitis B, are covered under Medicare Part D; this includes the vaccine for zoster.5 TABLE 4-1 Immunizations Indicated for Older Adults Even though older adults are less likely to get counseled for smoking cessation, they can successfully quit smoking and have demonstrated quit rates similar to that of younger adults. Despite common assumptions, older adults are not more likely than younger individuals to have nicotine addiction.6 Unfortunately, however, older adults are less likely to be exposed to smoking cessation interventions.7 The most commonly used model to promote individual smoking cessation is Prochaska’s transtheoretical model of change.8 Individuals are evaluated and encouraged to proceed through the following stages: precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality recommends the use of the “4 As” (ask, advise, assist, and arrange follow-up) in patients ages 50 and older, counseling interventions, physician/health care provider advice, buddy support programs, age-tailored self-help materials, telephone counseling, and the nicotine patch as effective interventions to facilitate smoking cessation in adults 50 and older. There is Medicare coverage to implement these interventions for up to eight visits per year. Polypharmacy is the use of more medications than are clinically needed or indicated. Older adults are particularly at risk for polypharmacy because of multiple comorbidities and the risk of seeing multiple health care providers. The best way to prevent polypharmacy is to avoid unnecessary medication use and attempt to implement behavioral interventions as a first line of treatment. Specifically, dietary interventions, exercise, stress management, and behavioral management techniques will often be sufficient if implemented and adhered to. Moreover, combining behavioral interventions with medications may allow for lower drug dosages to be used. Clinicians should also make certain to be very clear about drug use instructions and provide both verbal and written accounts of how to use the medication. Drug regimens should be simplified, and medications should be reviewed at each provider–patient interaction (see Chapter 6). The prevalence of current alcohol use tends to decrease with increasing age, with results in 2010 showing a decrease from 65.3% among 26- to 29-year-olds to 51.6% among 60- to 64-year-olds and 38.2% among people 65 or older.9 The rate of binge drinking among persons 65 or older in 2010 was 7.6%, and the rate of heavy drinking was 1.6% in this age group. The most reliable alcoholism-screening instruments are self-report questionnaires. Screening instruments vary in their ability to detect different patterns and levels of drinking and in the degree of their applicability to specific subpopulations and settings. The CAGE (Box 4-1) questionnaire10 is commonly used among clinicians. When used with older adults, it has reported sensitivities ranging from 43% to 94% for detecting alcohol abuse and alcoholism. The CAGE questionnaire is well suited to busy primary care settings because it poses four straightforward yes/no questions. It may fail, however, to detect low but risky levels of drinking and often performs less well among women and minority populations. Other measures include the 25-question Michigan Alcohol Screening Test (MAST),11 which was revised to be more relevant for older adults,12 or the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test.13 (See also Chapter 34.) The signs and symptoms associated with alcohol abuse in the older adult are numerous and include the same spectrum of physical, behavioral, and psychological problems that can be found in younger individuals. Conversely, however, a number of health benefits have been associated with moderate alcohol consumption.14 Specifically, there is evidence to suggest that one to two standard drinks has a positive effect on lipid metabolism,15 results in decreased mortality following a myocardial infarction, decreases risk of developing congestive heart failure, and may lower the risk of ischemic stroke in the young-old (60 to 69 years of age).16 In several large epidemiologic studies17,18 an association between alcohol and cognition suggests that moderate alcohol use was not associated with cognitive decline. A substantial body of scientific evidence indicates regular physical activity can bring dramatic health benefits to older adults (Table 4-2). Moreover, physical inactivity increases one’s risk of dying prematurely, of dying of heart disease, and of developing diabetes, colon cancer, and high blood pressure. Physical activity allows older individuals to increase the likelihood that they will extend years of active independent life, reduce disability, optimize mental health, and improve their quality of life in midlife and beyond.19–22 TABLE 4-2 Health Benefits of Physical Activity for Older Adults *A = supported by one or more high quality randomized trials; B = supported by one or more high quality nonrandomized cohort studies or low-quality RCTs; C = supported by one or more case series and/or poor quality cohort and/or case-control studies; D = supported by expert opinion and/or extrapolation from studies in other populations or settings Older adults need to regularly engage in both aerobic and resistive exercise weekly to optimize health.23 Older adults should also do exercises that maintain or improve balance if they are at risk of falling. Specifically, clinicians should recommend that older adults engage in 150 minutes of moderate intensity physical activity weekly. This activity should be done in at least 10-minute spurts and should be spread throughout the week. Moderate intensity of activity is defined as physical activity that is done at 3.0 to 5.9 times the intensity of rest. On a scale relative to an individual’s personal capacity, moderate intensity physical activity is usually a 5 or 6 on a scale of 0 to 10.24 Activities such as brisk walking, dancing, swimming, or biking are considered moderate intensity activities. Resistance training or muscle strengthening should also be done 2 days a week and should include all the major muscle groups (legs, hips, back, abdomen, chest, shoulders, and arms).23,25 Generally 8 repetitions of each exercise are recommended and the amount of resistance will vary for each individual. The individual should use a weight that can be comfortably lifted for the full 8 repetitions. Balance exercises, such as backward walking, sideways walking, heel walking, toe walking, and standing from a sitting position should be done at least 3 days a week. Initiation of a moderate intensity exercise program is safe for all older adults.26,27 Moreover, there is evidence to support that engaging in sedentary lifestyles increases risks to cardiovascular health.28 If the clinician feels that it will be helpful to the older adults to go through some type of screening, the Exercise and Screening for You screening tool27 can be completed. This interactive web-based tool can be done by the older adults or the clinician and provides assurance that, given no underlying clinical problems, the individual is safe to exercise. In addition the tool provides guidance for what type of exercises to do given underlying health concerns. There are also numerous resources available at no cost to guide the older adult through resistive exercise programs and aerobic activities such as those from the National Institute of Aging25 and the Centers for Disease Control.29 Nutritional health is important to consider in older adults because it can reflect medical illness, depression, dementia, inability to perform the functional tasks of shopping or cooking, inability to self-feed, financial challenges, or poor oral health, among other problems. In addition, nutrition contributes to frailty. A low body mass index (kg/m2 ≤20) or an unintentional weight loss of ≥10 lbs in 6 months suggests poor nutrition and should be evaluated. For older adults there is a general decline in calorie needs resulting from a slowing of metabolism and a decrease in physical activity. Nutritional requirements, however, generally remain the same. MyPlate for older adults addresses the needs of older adults based on the 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans.30 Table 4-3 lists the recommendations in MyPlate. MyPlate for older adults replaces the Modified MyPyramid for older adults. The following foods, fluids, and physical activities are represented on MyPlate for older adults: bright colored vegetables; deep colored fruits; whole, enriched, and fortified grains and cereals; low-fat and nonfat dairy products; dry beans; nuts; fish; poultry; lean meat; eggs; liquid vegetable oils; soft spreads low in saturated and trans fat; spices to replace salt; fluids such as water and fat-free milk; and physical activity including walking, resistance training, and light cleaning. Icons are used to facilitate understanding. TABLE 4-3 MyPlate Guidelines for Older Adults Adapted from U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary guidelines for Americans, 2010. 7th ed. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; December 2010.

Wellness and prevention

Essentials of health promotion for aging adults

Prevention of disease

Immunizations

Vaccine

Indicated for Older Adults

Influenza

1 dose annually

Tetanus, diphtheria, pertussis (Td/Tdap)

1-time initial dose and a booster every 10 years with Td

Varicella

2 doses are needed if the individual has never had varicella

Zoster

1 dose

Measles, mumps, rubella

1 dose if never had the diseases—adults born before 1957 are assumed, however, to be immune.

Pneumococcal

1 dose unless high risk and then may be revaccinated once in 5 years after initial vaccination.

Hepatitis A

Vaccinate only if at high risk/seeking protection from hepatitis A (behavioral risk factors; occupational risk factors; travel to countries that have high or intermediate endemicity of hepatitis A)

Hepatitis B

Vaccinate only if at high risk as noted above

Risk factor reduction through lifestyle behaviors

Smoking cessation

Prevention of polypharmacy

Screening for alcohol use/abuse

Health benefits and risks of alcohol use

Physical activity

Guidelines for physical activity

Guidelines for screening before exercise

Maintaining optimal nutritional intake

Age-relevant requirements

Foods to Reduce

Foods to Increase

Weight Management

Reduce daily sodium to less than 2300 mg; further reduce to 1500 mg for those ≥51 years and those at any age who are African American, hypertensive, diabetic, or suffering from chronic kidney disease.

Consume <10% of calories from saturated fatty acids and replace them with monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids.

Consume <300 mg per day of dietary cholesterol.

Keep trans fatty acid consumption as low as possible by limiting foods that contain synthetic sources of trans fats, such as partially hydrogenated oils, and by limiting other solid fats.

Reduce the intake of calories from solid fats and added sugars.

Limit consumption of foods that contain refined grains, especially refined grain foods that contain solid fats, added sugars, and sodium.

Keep alcohol intake to one drink per day for women and two drinks per day for men.

Increase vegetables and fruits

Consume at least half of total grains consumed as whole grains.

Increase intake of fat-free or low-fat milk/milk products.

Choose various protein foods (seafood, lean meat, poultry, eggs, beans, peas, soy products, unsalted nuts, seeds).

Increase the amount and variety of seafood consumed.

Replace protein foods high in solid fats with food lower in solid fats/calories and/or sources of oils.

Use oils to replace solid fats.

Choose foods high in fiber, potassium, calcium, and vitamin D.

Prevent and/or reduce overweight and obesity through improved eating and physical activity.

Control total calorie intake to manage body weight.

Increase physical activity and reduce time spent in sedentary behaviors.

Maintain appropriate calorie balance during each stage of life.

Wellness and prevention