Viral Hepatitis

Mary E. Romano

Lynette A. Gillis

KEY WORDS

Hepatitis A

Hepatitis B

Hepatitis C

Hepatitis vaccine

Viral hepatitis

Hepatitis refers to inflammation of the liver due to infectious or noninfectious causes. Infectious causes include hepatitis viruses (HAV, HBV, HCV, HDV, and HEV), Epstein-Barr virus, and Cytomegalovirus. This chapter will specifically discuss types A, B, C, D, and E. The majority of viral hepatitis in the US is caused by hepatitis A, B, and C.

HAV is an RNA virus in the Picornaviridae family.

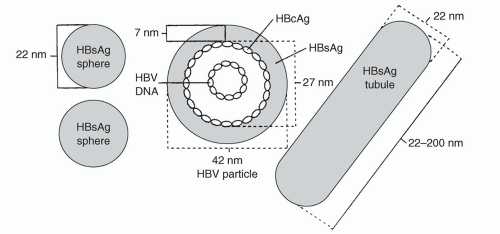

HBV is a DNA virus in the Hepadnaviridae family. The virion, also referred to as a Dane particle, is 42 nm in diameter. The circular DNA virus is contained in a 28 nm core surrounded by a 7 nm lipid envelope (Fig. 30.1).

Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) is contained within a lipid envelope.

Hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg) surrounds the circular DNA virus.

Spherical and tubular particles (20 to 22 nm) may be found circulating in the blood. These particles are excess virus coat material and contain HBsAg.

HCV is an RNA virus in the Flaviviridae family. There are seven major genotypes, more than 80 subtypes, and minor variants referred to as quasispecies. Genotype 1 is most common in the US. Treatment and anticipated response vary by HCV genotype.

HDV can only co-infect or superinfect in the presence of HBV. HDV is referred to as a subviral satellite due to its inability to cause infection on its own.

HEV is an RNA virus.

Hepatitis A

HAV is transmitted primarily through the fecal-oral route in contaminated food or water. HAV can be transmitted through close personal contact in group settings (household, day care, residential facility).

HAV does not cause chronic disease. Viral shedding is highest in the 2 weeks prior to onset of symptoms and is minimal approximately 1 week after the onset of jaundice. Infected children shed the virus longer than adults and are often asymptomatic, making them an important source of infection.

Overall, rates of hepatitis A have decreased by 90% in the last 10 years due to the expanded recommendations for vaccination of all children and adolescents.1 Rates were once higher for males, but are now similar for both genders.

Rates of hepatitis A are highest among young adults aged 20 to 29 years.2 Serologic evidence of hepatitis A increases with age as a result of natural infection and more widespread uptake of hepatitis A vaccine.

Hepatitis B

HBV is transmitted through percutaneous or permucosal exposure to infected bodily fluids and/or blood. This can occur through perinatal exposure, sexual contact, contaminated needles, or close personal contact with an infected individual (i.e., sharing personal items, contact with open sores or secretions). Among adults with HBV, about 60% report “no risk factors” for HBV infection.3 However, according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) data, when queried about selected behaviors, the most frequently reported risk factors among adults with HBV are ≥2 sexual partners (33%), men who have sex with men (MSM) (19%), and shared needles (18%).3

HBV may be found in the blood and all bodily secretions (saliva, breast milk, tears, stool, urine, semen, vaginal secretions, and respiratory droplets).

The estimated prevalence of hepatitis B is 0.4% in the US.4 Foreign-born persons have significantly higher rates of infection, particularly chronic HBV infection.

Incidence rates of acute HBV have continued to decline in all age-groups.2 In 2011, the highest incidence rates of acute HBV were seen in adults aged 30 to 39 years and the lowest in children <19 years. The greatest decline in acute incidence rates was in young adults aged 20 to 29 years. The acute incidence rates are higher in males than females, but this gap has narrowed in the last decade. The decline in infection rates is mostly attributed to HBV vaccination and a national strategy to eliminate HBV infection.

Hepatitis C

HCV is a blood-borne pathogen. The primary route of transmission is maternal-fetal in children and intravenous (IV) drug use in adolescents and young adults (AYAs).2 Sexual exposure, particularly MSM, is the next highest risk factor. Screening procedures have essentially eliminated HCV infection related to transplantation or receipt of blood products.

Rates of acute HCV infection have increased 45% from 2007 to 2011.2 The largest rate of increase was seen in those 0 to 19 years (0.05 to 0.1/100,000) and 20 to 29 years of age (0.75 to 1.18/100,000).

An estimated 75% to 85% of newly infected individuals will develop chronic HCV infection.5 There are an estimated 3.2 million people in the US with chronic HCV, making it the most common blood-borne infection. Although prevalence rates are highest in adults aged 45 to 68 years, isolated reports have shown increasing rates among AYAs (15 to 24 years).2 AYAs with reported IV drug use are at highest risk.

There have been significant increases in screening efforts for pregnant women, blood donors, and individuals at risk for HCV infection. In 2010, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved point-of-care testing for HCV in order to expedite notification of results and referral to care.5

Hepatitis D

HDV is transmitted primarily through blood and sexual contact and only in those already infected with HBV. It is uncommon in children, but can be acquired by AYAs with preexisting HBV infection. Risk factors include IV drug use and high-risk sexual activity, particularly MSM. The risk from contaminated blood and clotting products has been reduced in recent years due to improved screening techniques.

Hepatitis E

HEV is transmitted though the fecal-oral route and is largely the result of contaminated water. Animals are thought to be a reservoir for this virus.

Hepatitis E is a significant problem in developing countries and is endemic in Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. Seroprevalence rates in North America and Europe are between 1% and 3%.6 Cases of HEV in North America and Europe were previously thought to be due to travel; however, recent studies have identified strains that are distinctly different from those found in endemic developing countries.7

Symptoms

It is impossible to determine the cause of hepatitis based on the initial clinical presentation. If the date of exposure is known, the incubation period may suggest the diagnosis. The approximate incubation period for these diseases are as follows2:

Hepatitis A: 2 to 6 weeks

Hepatitis B: 2 to 6 months

Hepatitis C: 2 weeks to 6 months

Hepatitis D co-infection: 2 to 3 months

Hepatitis D superinfection: 2 to 8 weeks

Hepatitis E: 2 weeks to 3 months

Early viral hepatitis is often characterized by right upper quadrant pain and flu-like symptoms, including fatigue, low-grade fever, malaise, myalgias, and arthralgias. Cholestasis may also be present, resulting in acholic stools, dark urine, and jaundice.8

About 20% of individuals with hepatitis A will present with diarrhea.8

Hepatitis B is associated with arthritis, arthralgias, and rash due to circulating immune complexes.8 The arthritis is usually symmetric, affects smaller joints and typically spares the feet. Rash is present in patients with HBV up to 50% of the time and is typically urticarial although maculopapular and petechial rashes have been reported.

Laboratory Findings

Laboratory findings include relative lymphocytosis, elevated transaminases, elevated total/conjugated bilirubin, and mild elevation of alkaline phosphatase.8,9 Only 20% of patients with HCV infection develop symptoms with acute illness.9

The CDC case definition for acute hepatitis requires the discrete onset of symptoms and either jaundice or elevated serum transaminase levels. Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) is often more significantly elevated than aspartate aminotransferase (AST) unless cirrhosis is already present.8,9 In more serious disease, decreased albumin and increased prothrombin time are present. Decreased serum complement is found in patients with HBV arthritis. Joint fluid contains white blood cells ranging from 2,000 to 90,000 cells/mL.

Laboratory evaluation for viral antigens/antibodies can help to differentiate the causative agent. CDC laboratory criteria for diagnosis of acute hepatitis are as follows10:

Hepatitis A—CDC criteria for acute hepatitis A10:

Immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibody to HAV (anti-HAV).

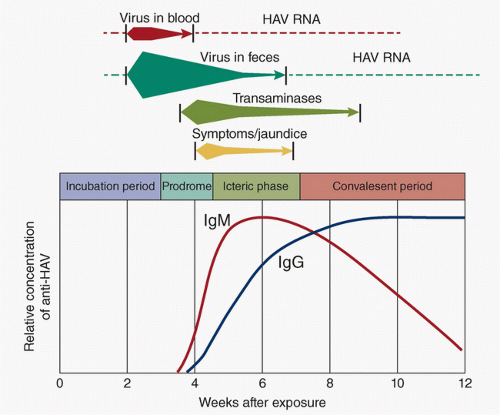

HAV in stool is the first marker. It is shed in stool 2 weeks before and 1 week after the onset of jaundice and corresponds to the period of greatest infectivity. Children can shed HAV for months, much longer than adults infected with HAV. A carrier state does not occur. IgM anti-HAV antibodies are present 5 to 10 days prior to the onset of

symptoms and remain positive for up to 6 months. IgG anti-HAV antibodies rise much more slowly and remain positive conferring lifelong protection (Fig. 30.2).

2. Hepatitis B—CDC criteria for acute hepatitis B10:

HBsAg positive and

IgM antibody to HBV core antigen (anti-HBc) positive

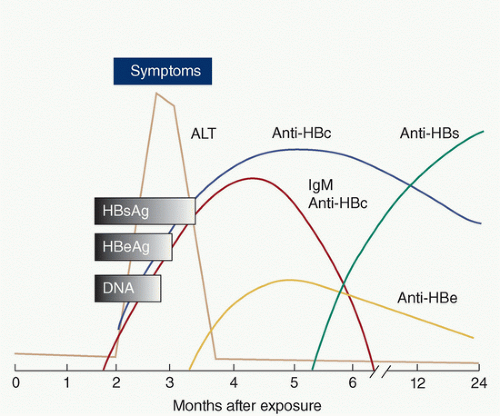

Figure 30.3 details the course of hepatitis b serology.

HBsAg becomes positive about 1 month after acute exposure and is usually undetectable by 15 weeks, although some individuals have persistence of this antigen for life. The presence of HBsAg indicates either acute HBV infection or a carrier state and the ability to transmit HBV.

Anti-HBsAg antibodies develop during convalescence or as a result of immunization and indicate immunity to disease.

Anti-HBcAg antibodies (HBcAb) appear in the window between the disappearance of HBsAg and the appearance of anti-HBsAg antibodies. Anti-HBcAg IgM and IgG appear simultaneously, but IgM disappears by 8 months. The presence of IgG antibodies alone indicates infection of >6 months duration.

HBeAg appears during the incubation period, and its presence indicates active viral replication and high infectivity. Persistence of HBeAg positivity beyond 12 weeks indicates likely progression to a chronic carrier state. The appearance of anti-HBeAg antibodies coincides with the disappearance of HBeAg and serves as a marker of decreased viral activity and infectivity. Table 30.1 summarizes the infectivity risk of HBV. Reactivation of disease can occur, particularly in immunosuppressed states. When reactivation occurs, there is reemergence of HBeAg and disappearance of anti-HBeAg antibodies.

HBV DNA can be measured and quantified, but it is not routinely used for diagnosis. It may be used to help monitor response to therapy.

3. Hepatitis C: CDC criteria for acute hepatitis C10:

Antibody to HCV (anti-HCV) screening-test-positive. (Criteria for positive values for specific lab assays as per CDC can be found at http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/HCV/LabTesting.htm) or

HCV recombinant immunoblot assay (HVC RIBA) positive or

HCV RNA nucleic acid test (NAT) positive (including qualitative, quantitative or genotype testing)

And, if done, meets the following two criteria:

Absence of IgM antibody to hepatitis A virus (IgM anti-HAV) and

Absence of IgM antibody to HBcAg (IgM anti-HBc)

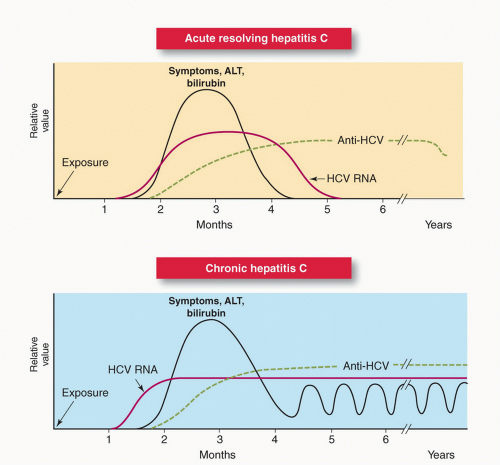

HCV antibodies are detectable about 7 weeks after exposure and are positive for life.

HCV RNA may be detected as early as 2 weeks after exposure to the virus.

TABLE 30.1 Infectivity for Acute Hepatitis B Virus

HBsAg

Anti-HBc

HBeAg

Anti-HBe

Infectivity

+

+

+

–

Acute infection or chronic carrier; very infectious

+

+

–

–

Acute or recent infection; possible chronic carrier state; moderately infectious

+

+

–

+

Recent infection or chronic carrier state; good prognosis; probably low infectivity

Anti-HBc, antibody to hepatitis B core antigen; anti-HBe, antibody to hepatitis B e-antigen; HBeAg, hepatitis B e-antigen; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen.

Antibodies against HCV may not be detected in infected patients who are immunocompromised or receiving dialysis. In contrast, patients with autoimmune disease may have a false positive test for HCV antibodies.

Chronic HCV disease is characterized by persistence of HCV antibodies and HCV RNA. A single negative test for HCV RNA using currently available NAT testing is considered sufficient to rule out chronic infection in an antibody-positive individual with no ongoing exposure. However, HCV RNA testing may be transiently negative as HCV antibodies are rising and so the CDC recommends repeat RNA testing ≥6 months after exposure for definitive diagnosis (Fig. 30.4).

4. Hepatitis D

There are no US FDA-approved tests for HDV. Commercial testing is available.

Infection with HDV can occur only with or after HBV infection. Superinfection is more likely to result in chronic disease than co-infection. Anti-HDV antibodies (IgM and IgG) are detected in acute and chronic infections, with persistence of antibodies in chronic infection. Delta antigen (HDVAg) has been documented in 20% of patients with acute infection.10 Since there is no FDA-approved test for delta antigen in the US, definitive diagnosis of chronic HDV is made by immunohistochemical analysis of liver tissue for HDV.10

5. Hepatitis E

There are no FDA-approved tests for HEV. Commercial testing is available.

Hepatitis A: Acute hepatitis A has an abrupt onset. Symptoms generally vary by age. Approximately 70% of older children, adolescents, and adults have symptomatic infection. Clinical infection does not usually last longer than 2 months; however, 10% to 15% of individuals have relapsing signs and symptoms of illness. HAV can cause fulminant hepatitis or autoimmune hepatitis.11

Hepatitis B: Clinical signs and symptoms of acute hepatitis occur more often in AYAs. While perinatal HBV acquisition is almost always asymptomatic, up to 50% of AYAs will present with acute clinical signs and symptoms after HBV exposure.11 When symptomatic, prodromal symptoms last about 10 days prior to onset of jaundice. Jaundice lasts 1 to 3 weeks although malaise and fatigue may last for months following initial infection. Pregnant women with acute HBV infection are at significantly higher risk of acute liver failure and death. The risk of progression to chronic disease decreases with age. Only 2% to 6% of adults progress to chronic infection compared to 90% of infected infants and 30% of children <5 years.12

The majority of individuals who develop chronic HBV infection are asymptomatic but capable of transmitting the infection. A minority of individuals with chronic HBV are not only infectious but also have active liver disease with abnormal serum transaminases. The risk of premature death from cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is 15% to 25% in chronic carriers.11 Adults who have had a chronic HBV infection since childhood develop HCC at a rate of 5% per decade. Up to 25% of infants and older children who acquire HBV infection eventually develop HCC or cirrhosis.11

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree