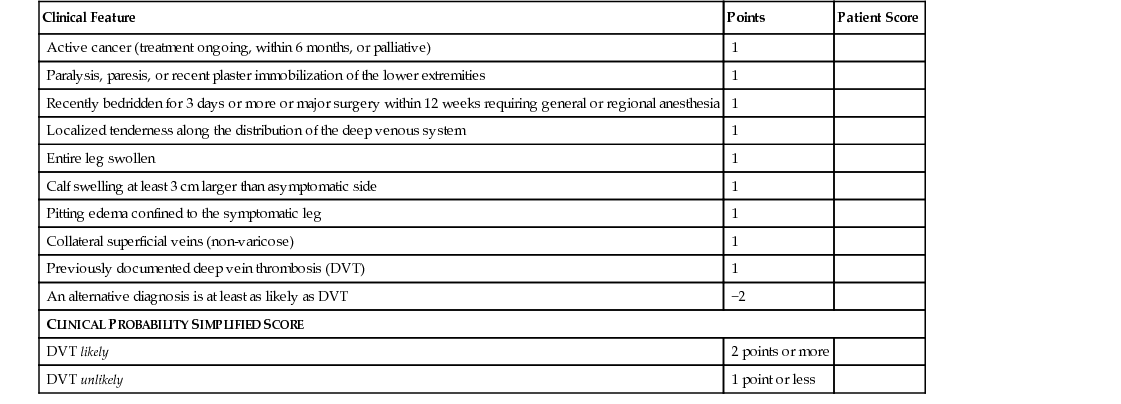

Hamsaraj G.M. Shetty, Philip A. Routledge Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is the third most common cardiovascular disease and an important cause of morbidity and mortality. Older people account for nearly two thirds of episodes.1 Between 65 and 69 years of age, annual incidence rates per 1000 for deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) are 1.3 and 1.8, respectively, and rise to 2.8 and 3.1 in individuals aged between 85 and 89 years. Older men are more likely than women of similar age to develop PE. About 2% develop PE and 8% develop recurrent PE within 1 year of treatment for DVT.2 VTE causes 25,000 to 32,000 deaths in hospitalized patients in the United Kingdom. It accounts for 10% of all hospital deaths. This, however, is likely to be an underestimate because many hospital deaths are not followed by a postmortem examination. The cost of managing VTE in the United Kingdom is estimated to be approximately 640 million pounds.3 About 25% of patients treated for a DVT subsequently develop debilitating venous leg ulceration, the treatment of which is estimated to cost 400 million pounds in the United Kingdom.3 The most serious complication of VTE is PE, which untreated has a mortality of 30%. With appropriate treatment, mortality is reduced to 2%.3 The diagnosis of VTE is often delayed until the occurrence of a clinically obvious (and occasionally fatal) PE. The diagnosis of PE is more often missed in older people and is sometimes made only at postmortem. The Virchow triad (named after Rudolf Virchow, 1821–1902) describes the three main predisposing factors for development of thrombosis. The first is alteration in blood flow, which may be reduced in people with heart failure (a common problem in older people) and in less mobile individuals. The second factor, injury to the vascular endothelium, is more relevant to arterial thromboembolism than to VTE. The third factor, hypercoagulability, is important because increases in clotting factor concentration, platelet and clotting factor activation, and a decline in fibrinolytic activity have all been reported in older people.4 The risk factors for VTE are well recognized (Box 47-1). Many of these (e.g., poor mobility, hip fractures, stroke, and cancer) are more frequently present in older people, who are also more likely to be hospitalized. Hospitalization is associated with an increased risk of VTE: the incidence is 135 times greater in hospitalized patients than in the community. The risk of VTE is greatest in medical inpatients, and it is estimated that 70% to 80% of hospital-acquired VTEs occur in this group. About a third of all surgical patients develop VTE before prophylactic treatments are used. A particular high-risk group is orthopedic patients. Without prophylaxis, 45% to 51% of orthopedic patients develop DVT. It is estimated that in Europe approximately 5000 patients per year are likely to die of VTE following hip or knee replacement, when prophylactic treatments are not given. Atypical antipsychotic agents are commonly prescribed in older people. The rate of hospitalization for VTE has been reported to be increased in association with risperidone (adjusted hazard ratio [AHR], 1.98; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.40-2.78), olanzapine (AHR, 1.87; CI, 1.06-3.27), clozapine and quetiapine fumarate (AHR, 2.68; CI, 1.15-6.28).5 Unilateral swelling of a leg is the most common feature in older patients with DVT.6 Calf pain may sometimes be present. A history of recent hospitalization for orthopedic surgery, stroke, or for some other illness is common. There may occasionally be a history of anorexia, weight loss, or other symptoms suggestive of an underlying neoplasm. It is well recognized that the clinical diagnosis of DVT can be difficult because the physical signs may often be absent or subtle, and the diagnosis may be more difficult in older people. Some individuals may be unable to complain about a swollen leg because of dementia, delirium, or dysphasia. In addition, other conditions mimicking DVT, such as a ruptured Baker cyst, are also more likely to occur in this age group. The clinical diagnosis of DVT relies on observing a swollen, warm, lower limb, which may sometimes be associated with engorged superficial veins. The Wells score attempts to take all relevant circumstances, symptoms, and signs into account and has been recommended as a useful initial screening test to ascertain whether DVT is likely or unlikely.7 Calf tenderness may also be present. If there is a difference of more than 2 cm in circumference between the two lower limbs, DVT must be excluded by appropriate investigations, unless there is another obvious explanation. Doppler ultrasonography has a sensitivity of 96% and specificity of 98% for a proximal DVT and so it is the investigation of first choice to diagnose a DVT. Contrast venography may be necessary in selected patients, especially if clinical suspicion is high and the Doppler scan is negative. Estimation of the concentration of D-dimer (a fibrin degradation product of thrombolysis), especially when combined with a clinical probability score such as the two-level DVT Wells score8 (Table 47-1), can be clinically useful. Wells and coworkers have shown that DVT can be ruled out in a patient who is judged clinically unlikely to have DVT and who has a negative D-dimer test. They suggest that that ultrasound testing can be safely omitted in such patients. In patients with suspected DVT and a “likely” two-level DVT Wells score, the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines recommend proximal leg vein ultrasound scanning within 4 hours and, if the result is negative, a D-dimer test should be performed. If the proximal leg vein ultrasound scan cannot be done within 4 hours, a D-dimer test should be performed. If the test results are positive, an interim 24-hour dose of a parenteral anticoagulant should be administered and, thereafter, a proximal leg vein ultrasound scan carried out within 24 hours.8 The guidelines further recommend that the proximal leg vein ultrasound scan should be repeated 6 to 8 days later for all patients with positive D-dimer test results and a negative proximal leg vein ultrasound scan. In those patients in whom DVT is suspected and with an “unlikely” two-level DVT Wells score, a D-dimer test should be carried out, and if the result is positive, either a proximal leg vein ultrasound scan should be conducted within 4 hours of being requested or an interim 24-hour dose of a parenteral anticoagulant (if a proximal leg vein ultrasound scan cannot be carried out within 4 hours) should be administered and a proximal leg vein ultrasound scan (carried out within 24 hours of being requested) should be offered.8 Sudden onset of dyspnea is the most common presenting feature of PE in older people. Sudden onset of a pleuritic chest pain, cough, syncope, and hemoptysis are other common presenting symptoms. In an older patient with stroke or recent orthopedic surgery, onset of any of these symptoms should greatly increase the suspicion of underlying PE. Because of high incidence of cardiovascular disease and age-related decline in cardiovascular function in general, older people are less likely to tolerate cardiovascular decompensation because of moderate or severe PE. They are, therefore, more likely to have syncope after a PE.9 Patients with smaller PEs can have very nonspecific symptoms and thus the diagnosis is often missed in this group. Clinical features will depend on the severity of the PE. In patients with a moderate to severe PE, tachycardia, hypotension, cyanosis, elevated jugular venous pressure, right parasternal heave, loud delayed pulmonary component of the second heart sound, tricuspid regurgitation murmur, and pleural rub may be present. However, in patients with smaller PEs, clinical examination may be normal, except possibly for a sinus tachycardia. Unexplained tachycardia in a patient who is potentially at risk for VTE should alert the clinician to the possibility of PE. Arterial blood gas analysis is a useful initial test in patients with suspected PE. Presence of hypoxia, or worsening of preexisting hypoxia, makes the diagnosis more likely, unless there are other comorbid conditions to account for it. An electrocardiogram (ECG) may show sinus tachycardia, S wave in lead I, Q wave and T inversion in lead III, right bundle branch block or a right ventricular strain pattern. In patients with severe PE, a P “pulmonale” may be seen. New onset of atrial fibrillation also can be a feature of PE. A chest radiograph may show elevated hemidiaphragm, atelectasis, focal oligemia, an enlarged right descending pulmonary artery, or a pleural effusion. Many older patients have coexistent cardiac failure or chronic pulmonary diseases, which can also cause some of the radiographic abnormalities associated with PE. Computed tomography pulmonary angiography (CTPA) is increasingly being used as the diagnostic test for detecting a PE. A meta-analysis has indicated that the rate of subsequent VTE detection after negative CTPA results is similar to that following conventional pulmonary angiography.10 One randomized, single-blind, noninferiority trial demonstrated that CTPA is equivalent to a ventilation/perfusion (V/Q) scan in ruling out PE. In the study, CTPA also diagnosed PE in significantly more patients.11 The British Thoracic Society has recommended CTPA as the initial lung imaging modality of choice for nonmassive PE.12 It has largely replaced the V/Q scan as the investigation of first choice in older patients because of its greater ability to detect PE even in patients with coexistent cardiac and respiratory disease. The NICE guideline recommends that in patients in whom a PE is suspected and with a “likely” two-level PE Wells score8,13 (Table 47-2), an immediate CPTA or, if not available, immediate interim parenteral anticoagulant therapy followed by an urgent CTPA should be offered. A proximal leg vein ultrasound scan should be considered if the CTPA is negative and a DVT is suspected. In patients in whom a PE is suspected and with an “unlikely” two-level PE Wells score, a D-dimer test should be offered and, if the result is positive, an immediate CTPA or immediate interim parenteral anticoagulant therapy followed by a CTPA if a CTPA cannot be carried out immediately. TABLE 47-2 Two-Level Pulmonary Embolism Wells Score

Venous Thromboembolism in Older Adults

Introduction

Risk Factors

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Deep Vein Thrombosis

Pulmonary Embolism

Clinical Feature

Points

Patient Score

Clinical signs and symptoms of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) (minimum of leg swelling and pain with palpation of the deep veins)

3

An alternative diagnosis is less likely than PE

3

Heart rate > 100 beats/min

1.5

Immobilization for more than 3 days or surgery in the previous 4 weeks

1.5

Previous DVT/pulmonary embolism (PE)

1.5

Hemoptysis

1

Malignancy (on treatment, treated in the last 6 months, or palliative)

1

CLINICAL PROBABILITY SIMPLIFIED SCORES

PE likely

More than 4 points

PE unlikely

4 points or less

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree