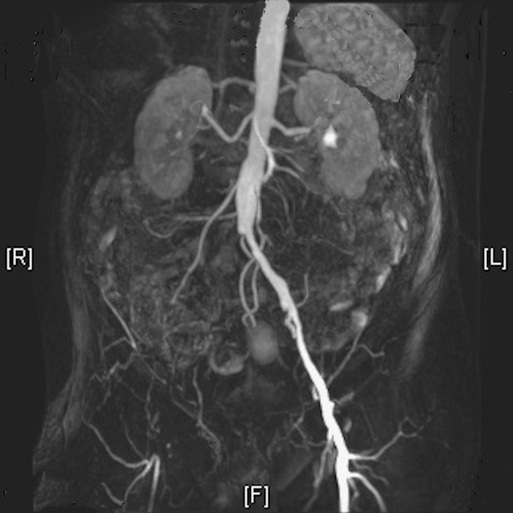

Charles McCollum, Christopher Lowe, Vivak Hansrani, Stephen Ball As the prevalence of atherosclerosis increases with advancing age, it is hardly surprising that specialists in geriatric medicine frequently find vascular disease in their patients. For many, their overall degree of frailty is such that neither detailed investigation nor vascular surgery will be indicated. However, vascular surgeons now routinely perform procedures in octogenarians and will increasingly do so as the population ages. Older adults suffer a range of vascular conditions. This chapter focuses on the four vascular problems of greatest concern to geriatricians: (1) limb ischemia; (2) abdominal aortic aneurysm; (3) carotid disease; and (4) chronic venous insufficiency, venous ulcers, and the swollen leg. Most older adult patients with peripheral artery disease (PAD) have chronic symptoms rather than acute leg symptoms. The spectrum ranges from intermittent claudication to critical limb ischemia (CLI) with rest pain, ulceration, gangrene, and the threat of limb loss (Figure 46-1). Vascular intervention is rarely indicated for intermittent claudication in older adults unless it significantly impairs quality of life. CLI is the tipping point in arterial insufficiency where stenosis and/or occlusion of the limb arteries, often at multiple levels, lowers the downstream perfusion pressure to the extent that nutritional flow to tissues is severely compromised, impairing wound healing or threatening tissue viability.1 Without urgent revascularization, tissue necrosis may occur within days or weeks and lead to major limb amputation. In contrast to intermittent claudication, where intervention is never urgent or even essential, CLI is an absolute indication for investigation with a view to angioplasty or surgery to restore adequate perfusion to the tissues of the foot. Acute limb ischemia is also common in older adults and can involve the upper or lower limb. There may be little or no significant arterial disease previously with embolization due to atrial fibrillation. Acute ischemia is often secondary to acute thrombosis in patients with PAD. Acute ischemia usually requires immediate (within 2 to 3 hours) investigation and treatment. As chronic PAD is often missed in older adults, its prevalence cannot be estimated reliably; however, the prevalence of intermittent claudication is approximately 7% in patients aged 70 years or older.2 The incidence of CLI is thought to be in the range of 500 to 1000 per million in Europe and the United States with prevalence of approximately 1% in patients aged 60 to 90 years.1 Intermittent claudication has a benign prognosis as perfusion of the tissues at rest is normal, but the peripheral arteries cannot deliver the 10-fold increase in blood flow required by exercising skeletal muscle. Only 10% of patients with claudication require vascular reconstruction, and with conservative care, most improve or remain stable. However, the risk of myocardial infarction and stroke in this group is similar to that of individuals with established coronary artery disease. A reduced ankle-brachial (pressure) index (ABI) as a result of PAD is associated with a three- to six-fold increase in cardiovascular mortality and all-cause mortality independent of the Framingham Risk Score.2 Managing cardiovascular risk is more important for most patients with claudication than investigation with a view to a vascular procedure. Management includes smoking cessation, optimization of blood pressure and diabetic control, and statin and platelet inhibitory therapy. Rest pain, ulceration, and gangrene indicate that tissue perfusion has begun to decompensate. Without prompt diagnosis and treatment, the outlook for patients with CLI is poor. Untreated CLI is associated with major amputation, disability, and death. Even following arterial reconstruction, 20% to 25% of patients will have died within a year and 25% to 30% will have suffered major amputation. Only 25% will be alive and free from signs and symptoms of CLI.2,3 Evaluation and Diagnosis The clinical history is critical; the pain of intermittent claudication is felt in the muscle, reproducibly develops with similar levels of exercise, and recovers within minutes of resting (without needing to sit down). CLI is associated with tissue loss and ischemic rest pain. Rest pain invariably occurs in the toes or forefoot unless there is acute limb ischemia involving the calf or even the whole leg. In individuals with CLI, elevation of the limb usually aggravates symptoms while dependency usually brings some degree of relief.4 Insonating blood flow in the ankle arteries using a handheld Doppler instrument and measuring the ABI is a simple bedside test that should replace the palpation of pulses, which is subjective and unreliable.1 In patients with leg pain, an ABI of 0.8 is more than 95% sensitive to PAD, but an exercise test is needed to exclude PAD; an ABI of greater than 0.9 after exercise effectively excludes PAD as a cause of symptoms or a threat to wound healing.5 It can be used as a first-line test in geriatric clinics or on the wards. Symptoms of CLI rarely develop in patients with an ABI greater than 0.5, but falsely high ABI may be measured in patients with calcified calf arteries. Any elevated ABI greater than 1.2 with a monophasic Doppler signal is almost certainly false because of calf artery calcification; symptomatic patients should be referred for a vascular opinion. If there is discrepancy between clinical signs and ABIs, particularly in patients with diabetes or chronic renal failure, further investigation should be dictated by clinical symptoms and signs. The inability to detect flow in the ankle arteries by Doppler, or measure an ankle arterial pressure, suggests very severe ischemia that needs emergent treatment. Noninvasive imaging by the vascular laboratory through the use of duplex Doppler ultrasound, computed tomographic angiography (CTA), or magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) has replaced invasive catheter digital subtraction angiography for most diagnostic purposes and for the planning of some interventions. Duplex ultrasound is now the first line of investigation for PAD and in general should be undertaken in all patients with symptoms sufficient to justify possible intervention. High-definition ultrasound is used to image the anatomy of the artery and any arterial disease and is combined with color Doppler to detect blood flow and quantify the severity of any stenosis.6–8 Duplex is operator dependent and is best undertaken by experienced clinical vascular scientists. Images can be limited by vessel calcification, and visualization of the iliac arteries is often unsatisfactory because of overlying bowel gas. Duplex ultrasound is ideal for imaging the carotids, abdominal aorta, and all the arteries in the limbs. Results can be used for planning procedures such as angioplasty and stenting.9,10 MRA is now widely available, avoids radiation, and allows detailed three-dimensional reconstruction of the entire arterial tree. The gadolinium contrast used carries little risk of contrast-induced nephropathy when used in recommended doses,11 although caution is still advised in patients with severe acute or chronic renal insufficiency (estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] < 30).12 MRA is the imaging modality of choice for planning of endovascular and surgical procedures when duplex imaging is insufficient, and it is particularly useful in assessing iliac disease (Figure 46-2). The sensitivity of MRA for segmental stenosis greater than 50% is 95% with a specificity of 96%, but the severity of stenoses are frequently overestimated.13 It is contraindicated in patients with pacemakers and other metallic implants, may not be tolerated by patients with claustrophobia, and is inaccessible for some very obese patients. When MRA is not possible, CTA is the alternative. Modern multidetector computed tomography scanners deliver high-quality arterial imaging with lower doses of radiation. The advantages of CTA over MRA include image acquisition with no signal “dropout” in previously stented vessels, patients’ preference for CTA, and less risk of overestimating the severity of stenosis. One disadvantage of CTA is that interference due to arterial calcification can obscure luminal narrowing or occlusion. The risk of contrast-induced nephropathy is an issue in older adult patients with chronic kidney disease, although this can be mitigated by prehydration.11 MRA is far easier to interpret, which is why it is more widely used than CTA to take images of PAD. All patients should be advised on managing cardiovascular risk. Statins reduce cardiovascular events in patients with PVD14 and can also prevent plaque instability and thrombosis by moderating endothelial function and inflammatory changes in the arterial wall.15 Platelet-inhibitory therapy is mandatory unless contraindicated, with clopidogrel being the initial drug of choice. Patients with claudication should be advised to stop smoking, lose weight if appropriate, and exercise with a view to improving their general fitness. Surgery or angioplasty for intermittent claudication should almost never be offered before a period of optimized medical care of at least 3 to 4 months. Vasodilator drugs such as naftidrofuryl are of minimal value and should probably be avoided.2,16 It is vital to recognize the onset of CLI, which requires urgent evaluation and treatment. Recent developments in endovascular therapy, such as drug-eluting balloons and stents, allow treatment of more complex lesions and also treatment of patients previously unfit for bypass surgery. However, because multilevel disease is usual in CLI, combined open surgery and endovascular procedures have become commonplace; for a patient with both iliac and femoral artery disease, the “inflow” can be treated by iliac angioplasty (with a stent if necessary) while the disease in the common or superficial femoral artery is treated surgically during the same procedure. For patients with superficial femoral artery disease and a life expectancy of greater than 2 years, the evidence is that a surgical “bypass first” approach achieves better long-term survival and limb salvage that an “angioplasty first” approach.17 The classic symptoms of sudden onset pain, pallor, pulselessness, loss of sensation, and loss of function indicate a surgical emergency. Sensory loss and loss of muscle function are the only signs that reliably discriminate acute from chronic ischemia. The palpation of pulses in unreliable and insonation of the ankle or wrist arteries by handheld Doppler is now essential. The underlying causes of acute ischemia include an embolus, frequently from the left atrium in atrial fibrillation in older adult patients or acute thrombosis of diseased arteries in patients with PAD. Iatrogenic arterial trauma during arterial catheterization (e.g., for coronary angiography) is also common in older adults. A bolus dose of intravenous heparin (5000 U) should be given to prevent propagation of the arterial thrombus before immediate transfer to a vascular service. Reperfusion should be achieved within 4 hours. The most frequent origin for an arterial embolus in older adults is the left atrium in atrial fibrillation or a mural thrombus following a myocardial infarction. Emboli may also arise from peripheral aneurysms or proximal arterial disease. Emboli commonly lodge at arterial bifurcations such as the aortic bifurcation (saddle embolus) or at the common femoral artery. Symptoms are often profound with a cold, white limb and loss of motor and sensory function. Numbness and sudden loss of sensation are ominous but frequently missed signs of a threatened limb. Immediate imaging by duplex Doppler ultrasound, CTA, or MRA defines the thrombus and should be performed urgently unless the cause is obvious (e.g., fractured long bone or a stab injury in young adults). Emboli lodged proximally in the limb or above the inguinal ligament are best removed surgically. Provided the limb is viable at presentation, embolectomy using a Fogarty catheter will usually restore limb perfusion. Embolism to the upper limb is usually only seen in older adults. The hand and arm are often viable because of the excellent collateral circulation around the shoulder. If the wrist pressure ratio on Doppler is higher than 0.6, most patients will recover fully with conservative care. If the wrist pressure ratio is lower than 0.6, many patients with a viable hand will experience long-term forearm claudication; surgery is usually indicated unless the patient is very unfit. Embolectomy under local anesthetic usually achieves a good result but is not a simple procedure, as closure of the small brachial artery usually requires a vein patch. In modern practice, lower limb acute ischemia is now more often caused by thrombosis of a diseased artery than a femoral embolus. The urgency of investigation is dictated by the severity of ischemia and particularly by whether there is sensation in the forefoot and toes. Patients with severe ischemia of the foot may still be able to wiggle toes if perfusion of the calf is adequate. Loss of sensation is an indication for reperfusion by surgery. Duplex imaging is ideal in the lower limb, whereas emergency MRA or CTA is more appropriate for aortoiliac disease. Provided motor and sensory function are intact, catheter-directed thrombolysis may be attempted initially.18–20 This usually involves catheterization of the thrombus and bolus dose of a thrombolytic (such as tissue plasminogen activator) followed by a continuous infusion over a period of 48 to 72 hours. Once thrombolysis has been achieved, any atherosclerotic stenosis should be treated by angioplasty/stenting or by arterial reconstruction as appropriate. Rupture of an abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is a catastrophic event, with at least 50% of deaths attributed to AAA rupture occurring before the patient reaches hospital.21,22 Ruptured AAAs cause approximately 8,000 deaths per year in the United Kingdom23 and approximately 15,000 deaths per year in the United States.24 Because the mortality is also high for patients that survive to reach the hospital and the operating room,25,26 management clearly focuses on early identification and treatment. Most AAAs are asymptomatic and are found incidentally during physical examination or investigation for another illness, most commonly during ultrasound for urologic diseases. Symptomatic aneurysms are now unusual, although low back and abdominal pain in a patient with an AAA should be attributed to the aneurysm in the first instance. The early survivors of AAA rupture have symptoms of collapse, severe back or abdominal pain, hypotension, and possibly hypovolemic shock. Patients with a retroperitoneal rupture have a better chance of reaching the hospital alive, as the initial hemorrhage is tamponaded by surrounding tissues. If the presence of an AAA is in doubt, a portable ultrasound in the emergency department may resolve the issue. The definitive diagnostic tool is CTA, which should be undertaken immediately after initial resuscitation unless shock is profound and immediate surgery essential. CTA confirms whether rupture has occurred and enables the surgeon to choose open or endovascular repair (Figure 46-3). Because the prevalence of AAA in men aged 65 to 75 is 4.9%, a national AAA screening program has recently been introduced throughout the United Kingdom.27–29 All men aged 65 are invited for ultrasound screening, and older men can request a scan. If the aorta is less than 3 cm in diameter, the patient is discharged. If the aorta is larger than 3 cm, the patient enters regular surveillance until the AAA grows to a diameter of 5.5 cm, the usual indication for repair in men. The risk factors for AAA are well established; these include male sex, advanced age, smoking, hypertension, and a family history in first-degree male relatives.30–33 Currently the aortic diameter used as the threshold for repair is 5.5 cm or greater in men and 5 cm or greater in women. This indication is based on large randomized trials in the United Kingdom34,35 and the United States.36 However, it is questionable whether these population-based findings are applicable to individual patients with AAAs. These trials were not designed to determine whether the indication for younger patients might be different for that in older patients. Current work focuses on providing more individualized indications for AAA repair37 and using computational modeling techniques to more accurately predict rupture risk in individual patients.38 The two main determinates influencing the decision to repair are (1) “fitness” for surgery, and (2) anatomic suitability for open or endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR). Detailed considerations of the anatomic criteria for conventional EVAR are beyond the scope of this chapter; however, the femoral and iliac arteries must be adequate as access vessels for introducing the stent graft, and the infrarenal aorta must provide a satisfactory proximal sealing zone. AAAs close to or involving the renal and visceral vessels are challenging in older adult patients, who are often unfit for open repair requiring aortic clamping above the renal arteries. Complex EVAR in octogenarians using fenestrated or branched grafts is now becoming routine in specialist centers but should not be considered minimally invasive. The procedures require general anesthesia and can last up to 5 hours. They require multiple sites of arterial access and high doses of nephrotoxic x-ray contrast. The decision not to repair can often be appropriate in octogenarians or in younger but unfit patients with multiple comorbidities. Regardless of whether open or endovascular repair is being contemplated, assessment of fitness to undergo repair and optimization of cardiac, pulmonary, and renal function are prerequisites. The majority of screen-detected AAAs will be approximately 5.5 cm with relatively low rupture risk (<5% per year), providing time to involve the appropriate medical specialties to optimize treatment. In our practice, all patients will undergo cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) as there is a growing evidence that CPET identifies patients at increased perioperative risk and predicts long-term survival.39–41 The evaluation of frailty, using a frailty index, has also been found useful in identifying patients who are at increased risk; this information can also be used in care planning.42

Vascular Surgery

Introduction

Arterial Disease of the Limb

Background

Peripheral Artery Disease

Epidemiology

Intermittent Claudication

Critical Limb Ischemia

Duplex Doppler Ultrasound

Magnetic Resonance Angiography

Computed Tomographic Angiography

Treatment

Acute Limb Ischemia

Management of Embolism

Management of Acute Thrombosis

Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm

Background

Symptoms and Presentation

AAA Screening

Elective Repair of AAAs

Indications

Assessment for Elective Repair

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Vascular Surgery

46