Vascular Lesions

Vascular lesions of the breast are a heterogeneous group. Most can be readily categorized histologically as benign or malignant. However, vascular lesions with atypical but not frankly malignant features have also been described. This chapter discusses the spectrum of vascular lesions that occur in the breast as well as pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia (PASH), a lesion with a histologic appearance that simulates a vascular lesion.

BENIGN VASCULAR LESIONS

Benign vascular lesions of the mammary parenchyma are relatively uncommon and several categories have been recognized including perilobular hemangioma, hemangioma (capillary, cavernous, and complex types), venous hemangioma, and angiomatosis. In addition, a variety of benign vascular lesions can involve the mammary subcutaneous tissue.1, 2, 3 and 4

The major clinical importance of these lesions is that they must be distinguished from angiosarcoma. In general, benign vascular lesions are circumscribed and lack the interanastomosing channels and the endothelial proliferation and atypia that characterize angiosarcomas.5 However, some angiosarcomas have areas that are extremely well-differentiated and simulate benign blood vessels. Conversely, some benign vascular lesions may show atypical cytologic or architectural features.6 For these reasons, the distinction between a benign vascular lesion and low-grade angiosarcoma may be impossible if the lesion is not completely excised or has only been sampled by a core-needle biopsy.

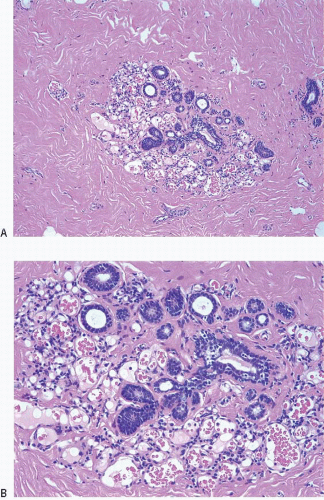

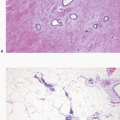

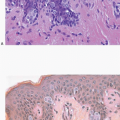

Perilobular hemangiomas are the most common vascular lesions of the breast. Their reported frequency ranges from as low as 1.2% to as high as 11% of breast specimens.7,8 They are capillary hemangiomas that are, by definition, of microscopic size and identified incidentally. They consist of a circumscribed collection of small, thin-walled, variably ectatic vascular spaces lined by relatively inconspicuous, flattened endothelial cells that lack cytologic atypia. Despite their designation as “perilobular,”

they may involve the intralobular stroma, interlobular stroma, or both (Fig. 12.1, e-Fig. 12.1). Rarely, perilobular hemangiomas exhibit endothelial cell atypia (“atypical perilobular hemangioma”).1

they may involve the intralobular stroma, interlobular stroma, or both (Fig. 12.1, e-Fig. 12.1). Rarely, perilobular hemangiomas exhibit endothelial cell atypia (“atypical perilobular hemangioma”).1

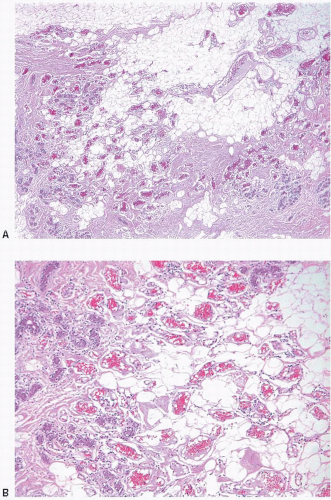

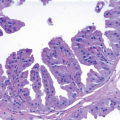

Hemangiomas are benign vascular lesions that are large enough to be detected clinically or mammographically.1 In general, they are microscopically well-circumscribed and lack endothelial cell atypia. However, in some cases, vessels extend into the surrounding breast parenchyma or adipose tissue, which produces a worrisome appearance resembling low-grade angiosarcoma. Mammary hemangiomas have been subcategorized as cavernous (featuring dilated blood vessels filled with erythrocytes), capillary (characterized by compact, sometimes lobular collections of small blood vessels that resemble a pyogenic granuloma), and complex (composed of a mixture of dilated vessels as seen in the cavernous type and small vessels as seen in the capillary type) (Fig. 12.2, e-Fig. 12.2). As with vascular lesions in other sites, thrombosis may occur; organizing thrombi may exhibit papillary endothelial hyperplasia, which produces a pattern that may be misinterpreted as an angiosarcoma (Fig. 12.3).9 In addition, some lesions with features otherwise characteristic of benign hemangiomas exhibit atypical changes, such as endothelial cell atypia or focally anastomosing vascular channels (“atypical hemangiomas”).6

Venous hemangiomas are rare lesions consisting of vascular structures that contain muscular walls of varying thickness. Again, the endothelial cells lining these spaces are relatively inconspicuous and lack cytologic atypia.4

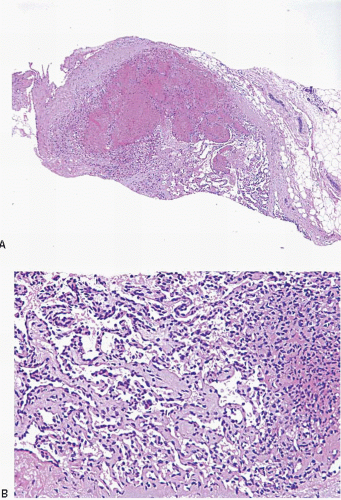

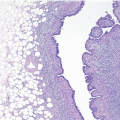

Angiomatosis is also a rare lesion composed of dilated, anastomosing vascular spaces that are similar to angiomatoses in other sites. The walls of these spaces may contain sparse, smooth muscle fibers and lymphocytes. Endothelial cell atypia is not present (Fig. 12.4, e-Fig. 12.3). Although these are benign lesions, they extend around mammary ducts and lobules and often involve large areas of the breast. In addition, angiomatosis lacks the circumscription that characterizes most other benign vascular lesions, and the distinction from a low-grade angiosarcoma may be difficult.2

ANGIOSARCOMA

Angiosarcomas are the most frequent primary sarcomas of the breast, but are still very uncommon and account for <0.05% of breast malignancies. They may arise spontaneously (primary angiosarcoma) or following radiation therapy for breast cancer (secondary angiosarcoma). Although angiosarcomas that develop after radiation may involve the mammary skin, breast parenchyma, or both, cutaneous angiosarcomas are more common than those involving the mammary parenchyma in the post-radiation setting.10, 11, 12 and 13 Angiosarcomas may also arise in the arm following radical mastectomy as the result of chronic lymphedema (Stewart-Treves syndrome); however, this is rarely seen in current practice where radical mastectomies are uncommonly performed.14

The age range at presentation of patients with angiosarcomas is broad, but patients with primary angiosarcomas are usually younger (median age 35 to 40 years) than those with post-radiation angiosarcomas (median age 59 to 69 years).

Angiosarcomas of the mammary parenchyma present as a painless mass; those that involve the skin may appear as areas of blue or violaceous discoloration.

On gross examination, the tumors range in size from <1 cm to >20 cm; most cases are >2 cm. Angiosarcomas most often appear as hemorrhagic masses (Fig. 12.5); larger tumors may have areas of necrosis or cystic degeneration. Smaller lesions may not appear grossly hemorrhagic.

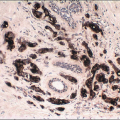

On microscopic examination, angiosarcomas are characterized by interanastomosing vascular spaces that dissect through the mammary stroma and adipose tissue and surround and invade lobules, disrupting the normal lobular architecture. The vascular spaces are lined by endothelial cells that show nuclear hyperchromasia. Variable degrees of stromal erythrocyte extravasation are present. In many angiosarcomas, the vascular spaces at the invasive edge of the tumor may appear extremely bland and may be difficult to distinguish from benign blood vessels.

FIGURE 12.5 Angiosarcoma. This hemorrhagic mass involves the mammary parenchyma and extends into the overlying skin. |

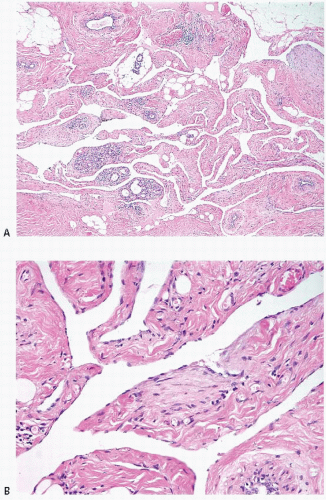

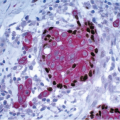

Angiosarcomas have been divided into low, intermediate, and high grade based on a combination of histologic features (Table 12.1).5 Lowgrade angiosarcomas are characterized by well-formed, anastomosing vascular channels that contain varying numbers of erythrocytes. Endothelial cell nuclear hyperchromasia is present, but mitoses are absent or scant. Papillary endothelial cell tufting and solid areas are absent (Figs. 12.6 and 12.7, e-Fig. 12.4). Some low-grade angiosarcomas are composed of vessels that have a capillary-like appearance. Intermediate-grade lesions show increased cellularity with endothelial cell tufts and papillary formations and/or the presence of solid spindle cell foci with few or no vascular lumina. Mitotic figures may be present in the more cellular areas (Fig. 12.8). High-grade angiosarcomas exhibit prominent tufts and papillations composed of cytologically malignant endothelial cells with readily identifiable mitoses. Solid spindle cell areas with little or no vascular lumen formation are often present, as are foci of stromal hemorrhage (“blood lakes”) and necrosis (Fig. 12.9, e-Fig. 12.5). In some high-grade angiosarcomas, the endothelial cells have an epithelioid appearance, and these lesions may be difficult to distinguish from carcinomas (Fig. 12.10).15 It should be noted that the grade may vary within a given lesion.

In the past, grading of angiosarcomas was thought to have prognostic importance. In the most widely cited study to address the relationship between grade and outcome, the 5-year survival was 76%, 70%, and 15% for low-, intermediate-, and high-grade angiosarcomas, respectively.16

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree