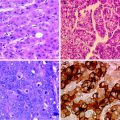

Fig. 1

Histologic features of fibrolamellar carcinoma. Hematoxylin-eosin stained photomicrograph demonstrates large hepatocellular tumor cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm and prominent nucleoli embedded in a lamellar, fibrous stroma

3 Presentation and Laboratory Diagnosis

Many patients present with symptoms, including abdominal pain and a palpable, painless abdominal mass. An unusual presentation is gynecomastia, caused by tumor cell expression of the enzyme aromatase, which converts androgens to estrogens [9, 10] Laboratory examination reveals normal serum alpha-fetoprotein levels but elevated values of des-γ-carboxy prothrombin (DCP), vitamin B12 binding capacity, and neurotensin. DCP, also known as prothrombin induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist II (PIVKA II), is an abnormal prothrombin produced by malignant hepatocytes with defective post-translational carboxylation of the prothrombin precursor. Serum DCP is used in the diagnosis and surveillance of conventional hepatocellular carcinoma. Its levels are reportedly elevated in 64–100 % of patients with fibrolamellar carcinoma [11, 12].

In 1973, extraordinary elevations of serum vitamin B12 and vitamin B12 binding protein were reported in 3 teenagers with primary liver cancer, likely fibrolamellar carcinomas [13]. A decade later, Paradinas and co-workers reported high serum levels of unsaturated vitamin B12 binding capacity (UBBC) in 7 of 8 cases of fibrolamellar carcinoma, contrasted with 3 of 99 cases of typical hepatocellular carcinoma [14]. More recently, serum vitamin B12 binding proteins have been measured for not only diagnosis but also surveillance of fibrolamellar carcinoma [12, 15] The mechanism for vitamin B12 binding protein elevation is not known but may involve tumor cell production of a protein that impedes uptake of vitamin B12 binding proteins by the reticuloendothelial system [13, 16].

Patients with fibrolamellar carcinoma also present with elevated levels of serum neurotensin, a peptide that regulates gut motility, secretion, and mucosal growth [17]. In the adult gastrointestinal tract, expression of the neurotensin gene is localized to the small bowel. In the liver, neurotensin gene expression has been identified in fetal human liver, reflecting the common embryologic origin of the gut and liver. It has also been detected in fibrolamellar carcinoma but not in adult liver or focal nodular hyperplasia. Neurotensin gene expression and elevated serum levels suggest a possible stem cell origin of fibrolamellar carcinoma.

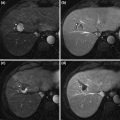

4 Radiologic Diagnosis

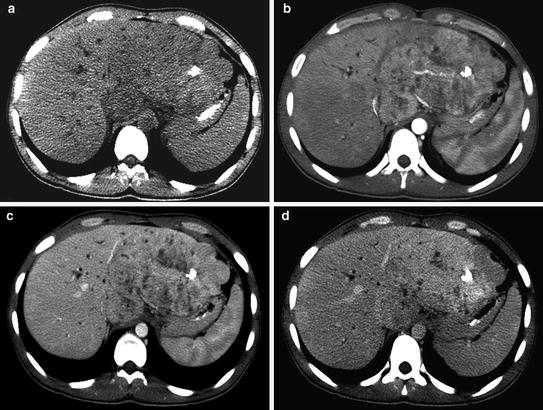

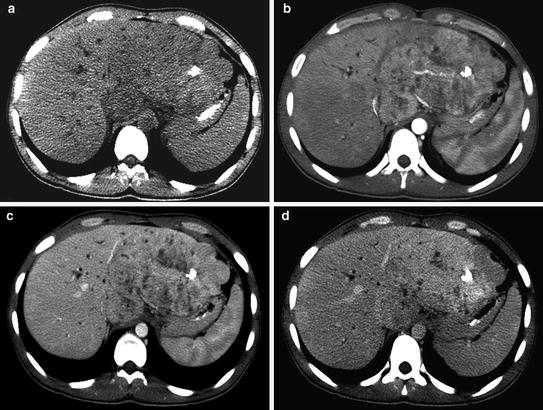

On ultrasound, fibrolamellar carcinoma presents as a large, solitary mass with well-defined, lobulated borders, and variable echotexture [18]. Unenhanced computed tomography (CT) demonstrates a hypoattenuating mass relative to surrounding normal liver (Fig. 2a). A central scar is reported in 20–75 % of cases and represents a coalescence of fibrous tissue with radiating fibrous bands [19, 20] Arterial and portal phase CT images demonstrate heterogeneous enhancement surrounding the central scar, if present (Fig. 2b, c). On delayed phases, fibrolamellar carcinoma is characterized by increasing homogeneity, as contrast washes out from more vascular portions of the tumor and fibrous lamellae take up contrast (Fig. 2d). Lymphadenopathy is detected in up to 65 % of patients, indicative of nodal metastases, typically in the porta hepatis [20].

Fig. 2

Unenhanced CT demonstrates a large, low-attenuation mass in the liver with calcifications (a). Arterial phase CT shows a central scar surrounded by heterogeneous enhancement (b), which becomes homogeneous on delayed phases (c, d)

On magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), fibrolamellar carcinoma is hypointense relative to surrounding non-neoplastic liver on T1-weighted sequences and hyperintense on T2-weighted sequences [18]. Similar to contrast-enhanced CT, gadolinium-enhanced MRI displays heterogeneous enhancement surrounding the central scar, which may exhibit delayed enhancement, persisting 10–20 min after contrast administration [18, 20].

Fibrolamellar carcinoma should be distinguished from focal nodular hyperplasia, which is a benign lesion, also characterized by a central scar. Fibrolamellar carcinoma is usually larger than focal nodular hyperplasia, with mean diameter exceeding 10 cm. Whereas calcification occurs in 35−68 % of fibrolamellar carcinomas, it is rarely seen in focal nodular hyperplasia [19, 20]. On arterial phase CT, the enhancement surrounding the central scar is heterogeneous in fibrolamellar carcinoma and homogeneous in focal nodular hyperplasia. On T2-weighted MRI, the central scar in fibrolamellar carcinoma is typically hypointense, unlike focal nodular hyperplasia, in which the central scar is hyperintense.

Radionuclide scans may be helpful in cases of diagnostic uncertainty with CT or MRI. In technetium-99m-labeled sulfur colloid scans, sulfur colloid uptake correlates with the reticuloendothelial activity of Kupffer cells, which are absent in fibrolamellar carcinoma [18]. Therefore, these scans will demonstrate a photopenic defect in the area of the tumor. In contrast, focal nodular hyperplasia will demonstrate normal or increased uptake of sulfur colloid. If the differential diagnosis includes hepatic hemangioma, then technetium-99m-labeled red blood cell scan can be useful, as fibrolamellar carcinomas exhibit increased arterial phase activity and a photopenic defect on delayed images. Hemangiomas demonstrate the reverse pattern–a photopenic area on arterial phase and increased activity on delayed images.

5 Treatment

The mainstay of treatment for fibrolamellar carcinoma is surgical resection. Owing to patients’ younger age and absence of cirrhosis, more aggressive surgery is feasible than in patients with typical hepatocellular carcinoma. For patients with unresectable tumors, orthotopic liver transplantation has been performed, with 3-year survival rates of up to 76 % [21]. The criteria for liver transplantation in fibrolamellar carcinoma are the same as those for conventional hepatocellular carcinoma, since poor outcomes have been reported after transplantation of patients with tumors beyond the Milan criteria [11].

Since 1995, there have been few published surgical series on fibrolamellar carcinoma with small numbers of patients (Table 1). All the studies are from North America or the United Kingdom, reflecting the predominance of this disease among Caucasians and its rarity in Asia [5, 6]. Most patients required major hepatectomy (resection of 3 or more segments) or liver transplantation. Unlike conventional hepatocellular carcinoma, lymph node involvement was common, occurring in up to 70 % of patients, but this did not preclude surgical resection. The incidence of vascular invasion ranged between 11 and 75 %. Recurrence rates were as high as 100 %, with a median time to recurrence of 2.2 years [22]. The most common sites of recurrence were liver, lung, and intra-abdominal lymph nodes. Many patients were amenable to resection of recurrent disease, with median survival of 26 months after re-resection in the series by Stipa and colleagues [23]. The 5-year overall survival of surgically treated patients was favorable, ranging between 50 and 76 %.

Table 1

Surgical series on fibrolamellar carcinoma published since 1995

Author, Year | No. of patients | Median age (range), years | Positive nodes (%) | Median size (range), cm | Solitary tumor (%) | Vascular invasion (%) | Recurrence rate (%) | 5-year overall survival (%) | Prognostic factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Pinna 1997 [11] | 41 (28 PHx, 13 OLT) | 25 (9–66) | 34 | 13 (3–25) | 73 | 75 | 66 | 66 | Positive nodes Vascular invasion |

Hemming 1997 [27] | 9 | Mean 31 (20–56) | 11 | Mean 8 | 78 | 11 | 67 | 70 | Positive nodes Vascular invasion Multiple tumors |

El-Gazzaz 2000 [21] | 20 (11 PHx, 9 OLT) | 27 (12–69) | 30 | 11 (2–22) | 80 | 55 | 45 | 50 | Positive nodes Vascular invasion Multiple tumors Size>5 cm Capsule invasion |

Stipa 2006 [23] | 28 | 27 (14–72) | 50 | 9 (3–17) | 89 | 32 | 61 | 76 | Positive nodes |

Maniaci 2009 [22] | 10 | 24 (16–50) | 70 | Mean 13 (8–20) | 50

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|