There is ongoing debate on how to reform the health care system. Value-based systems have been proposed to account for both quality and cost. The primary goal of value-based health care is to achieve good health outcomes for patients with consideration of dollars spent. To do so, it is imperative that health care providers define meaningful outcome metrics for specific medical conditions and consider the full cycle of care as well as multiple dimensions of care.

- •

Value-based health care proposes a model that evaluates health care based on 6 elements: safety, effectiveness, patient centeredness, timeliness, efficiency, and equity.

- •

The primary goal of value-based health care is to achieve an optimal health outcome with consideration of dollars spent for care.

- •

An integrated practice unit of care allows coordination of care for patients across medical disciplines, which expedites treatment and eliminates duplication of services.

- •

Successful programs for value-based health care have been implemented for organ transplantation, coronary and dialysis care, and in vitro fertilization.

One of the many challenges in quality research has been the translation of each of these quality components into measureable indicators so as to monitor and improve the quality of care at the population level. With respect to structure, surgical volumes have been the most extensively studied. However, the strength of the relationship between structure and outcomes varies widely. Process measures are the most widely used quality-measurement metrics. In theory, process measures should correlate with outcomes of care, but such associations have been difficult to show. In addition, although process measures may be useful metrics for institutions, they are not a substitute for outcomes, which are considered the only true measures of quality in health care. For example, even with highly selected process indicators or treatment guidelines targeted for compliance, there may be legitimate reasons for an individual patient to not receive guideline-based care (eg, clinician propensity, practice barriers, medical contraindications, or patient preferences). In addition, using adherence rates as a process measure is problematic because it can unintentionally promote the overuse of medical services. Traditional outcome indicators include morbidity, which assesses the unintended consequences of treatment in a measureable way, and survival and recurrence, which indicate whether a treatment is achieving its intended goal. However, consensus definitions for disease-specific outcomes do not exist and the comprehensive systematic measurement of outcomes is rare.

According to Michael E. Porter, MBA, PhD, of the Harvard Business School, the Institute of Medicine’s lack of clarity in defining the proposed 6 elements of quality health care (safety, effectiveness, patient centeredness, timeliness, efficiency, and equity ) has slowed progress in improving the performance of the health care system. To enhance the performance and accountability of the health care system, stakeholders must therefore abandon these individual quality-defining elements, which often represent conflicting goals, and concentrate on value as a single focus for health care delivery. Porter argues that the inability to measure value in health care has been the most serious failure in the medical community to date and has significantly impeded health care reform.

Value-based health care

In contrast with more traditional measures of health care quality, the primary goal of value-based health care is to achieve good health outcomes for patients with consideration of dollars spent. Value-based health care promotes a patient-centered program in which outcomes are evaluated by relevant patient outcomes rather than individual processes that contribute to outcomes. Another unique feature of value-based health care is that each medical condition has its own outcome measures that are precisely defined and assessed longitudinally. Along with disease-specific outcomes, total costs over time are considered to account for ongoing interventions and treatment-associated illnesses. The premise for value-based health care is that, if value provides overall improvement in health care systems, then all stakeholders (including patients, payers, and providers) benefit and economic sustainability is maintained.

One of the challenges in improving performance in health care has been in defining value, which, simply stated, is the patient health outcomes achieved plus the efficiency of the delivery of services as accounted for by costs. In this system, outcomes include the “results of care in terms of patients’ health over time” with consideration of complications of care, timeliness of care, and patient satisfaction. The full cycle of care in value-based health care includes diagnostic evaluation, acute care, related early and late complications, rehabilitation, and reoccurrences. Unlike current mechanisms of evaluation, value-based health care is measured over time at disease-specific intervals. These definitions of care and health are in contrast with those used in the current health care system, in which acute events are most often isolated from the care cycle and processes of care, or the volume of services delivered is often emphasized.

Outcome hierarchy

Given that, for any medical condition, there is no single outcome that captures the results of care in terms of patient health, proponents of value-based health care argue that the current system assesses outcomes in a manner that is either too broad or too narrow. For example, a patient with breast cancer who is diagnosed as tumor free would be considered to have a positive outcome in the narrow definition of breast cancer outcomes, but that patient may have ongoing symptoms associated with treatment (eg, posttreatment lymphedema) that result in a less favorable overall outcome. Similarly, assessment and reporting of hospital infection rates, mortality, medication errors, or surgical complications are outcomes that are too broad to provide evaluation of a provider’s care in a way that is meaningful for an individual patient, and they may also miss relevant treatment-associated complications and long-term sequelae.

To address these limitations of the current system, 4 principles have been defined in the value-based health care model to determine relevant multidimensional and disease-specific outcome measures: (1) relevant outcomes should be defined for individual medical conditions, (2) both short-term and long-term outcomes associated with these conditions should be considered within a care cycle that has a specified beginning and end, (3) outcome measures should include the full spectrum of contributing services and providers, and (4) outcome measures should adjust for individual risk factors and comorbidities.

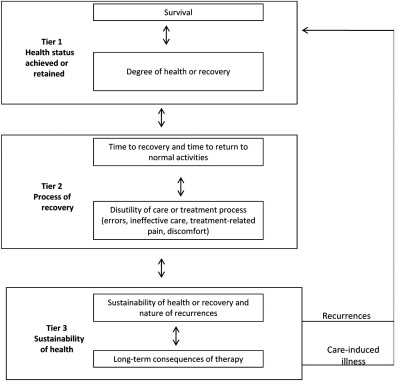

Porter proposed a 3-tiered hierarchy to account for the spectrum of outcomes for any medical condition ( Fig. 1 ). In this model, tier 1 represents patient health status achieved or retained, tier 2 the process of recovery, and tier 3 the sustainability of health. The outcomes depend on a progression of results that, in turn, depend on the success at higher tiers. Each tier consists of 2 dimensions that capture specific aspects of health.

Tier 1 is considered the most important of the three. The first dimension of tier 1 is patient survival, which is measured at condition-appropriate time intervals. The second dimension, degree of patient health or recovery, accounts for the full set of outcomes that are of significance to a patient and are related to the processes of recovery. Recovery is measured by the degree to which patients are able to return to their normal activities of daily living (ie, functional status) once condition-specific steady state has been achieved after treatment. For many cancers, recovery measures include functional outcomes, cosmetic results, and psychological state.

Tier 2 of the outcome hierarchy accounts for the processes (rather than degree) of recovery. The first dimension of tier 2 assesses the patient’s time to recovery and time to return to normal activities (ie, the best attainable level of function after diagnosis). This dimension is considered for each phase of care. Reducing the overall cycle time by reducing the time needed to complete various phases of care (eg, diagnosis, treatment planning, and initiation of treatment) is of major importance to patients. The second dimension of tier 2 accounts for the disutility of care or treatment process, such as adverse effects, diagnostic errors, treatment-related pain, ineffective treatment, and condition-specific complications related to treatment.

Tier 3 accounts for the sustainability of health, which “measures the degree of health maintained as well as the extent and timing of related recurrences and consequences” In this tier, the first dimension considers the recurrence of disease or long-term complications, whereas the second dimension captures new health conditions that occur as a consequence of treatment.

In this 3-tiered outcome model, improving 1 dimension benefits the others, and tradeoffs among outcome measures can be explicitly considered. For example, although there are limited treatment options for some metastatic cancers that do not influence survival (tier 1, first dimension) but may provide timely care, palliation of symptoms, and prolonged time to adverse consequences, thereby positively affecting tier 2 and tier 3 dimensions. An example of the hierarchical outcome model as applied for patients with locally advanced extremity soft tissue sarcoma is shown in Fig. 2 .

Each medical condition is associated with a unique set of outcome dimensions. Defining these outcomes must consider their “importance to patient, variability, frequency, and practicality.” To successfully define outcomes, information should be sought from focus groups, families, and patient advisories. In this value-based system, validated instruments (eg, for functional outcomes or quality of life) can be used to assess individual dimensions and to compare health outcomes across providers. Another critical element to capturing quality data longitudinally is an information technology infrastructure that can facilitate the extraction of clinical data for measurement purposes.

In summary, accountability for the value of health care should be shared by all physicians. Extensive outcome hierarchies for specific medical conditions provide a comprehensive measurement system that may result in improvements in care at the level of health care providers. In addition, future public reporting of such outcomes could ultimately “accelerate innovation by motivating providers to improve relative to their peers.”

Outcome hierarchy

Given that, for any medical condition, there is no single outcome that captures the results of care in terms of patient health, proponents of value-based health care argue that the current system assesses outcomes in a manner that is either too broad or too narrow. For example, a patient with breast cancer who is diagnosed as tumor free would be considered to have a positive outcome in the narrow definition of breast cancer outcomes, but that patient may have ongoing symptoms associated with treatment (eg, posttreatment lymphedema) that result in a less favorable overall outcome. Similarly, assessment and reporting of hospital infection rates, mortality, medication errors, or surgical complications are outcomes that are too broad to provide evaluation of a provider’s care in a way that is meaningful for an individual patient, and they may also miss relevant treatment-associated complications and long-term sequelae.

To address these limitations of the current system, 4 principles have been defined in the value-based health care model to determine relevant multidimensional and disease-specific outcome measures: (1) relevant outcomes should be defined for individual medical conditions, (2) both short-term and long-term outcomes associated with these conditions should be considered within a care cycle that has a specified beginning and end, (3) outcome measures should include the full spectrum of contributing services and providers, and (4) outcome measures should adjust for individual risk factors and comorbidities.

Porter proposed a 3-tiered hierarchy to account for the spectrum of outcomes for any medical condition ( Fig. 1 ). In this model, tier 1 represents patient health status achieved or retained, tier 2 the process of recovery, and tier 3 the sustainability of health. The outcomes depend on a progression of results that, in turn, depend on the success at higher tiers. Each tier consists of 2 dimensions that capture specific aspects of health.

Tier 1 is considered the most important of the three. The first dimension of tier 1 is patient survival, which is measured at condition-appropriate time intervals. The second dimension, degree of patient health or recovery, accounts for the full set of outcomes that are of significance to a patient and are related to the processes of recovery. Recovery is measured by the degree to which patients are able to return to their normal activities of daily living (ie, functional status) once condition-specific steady state has been achieved after treatment. For many cancers, recovery measures include functional outcomes, cosmetic results, and psychological state.

Tier 2 of the outcome hierarchy accounts for the processes (rather than degree) of recovery. The first dimension of tier 2 assesses the patient’s time to recovery and time to return to normal activities (ie, the best attainable level of function after diagnosis). This dimension is considered for each phase of care. Reducing the overall cycle time by reducing the time needed to complete various phases of care (eg, diagnosis, treatment planning, and initiation of treatment) is of major importance to patients. The second dimension of tier 2 accounts for the disutility of care or treatment process, such as adverse effects, diagnostic errors, treatment-related pain, ineffective treatment, and condition-specific complications related to treatment.

Tier 3 accounts for the sustainability of health, which “measures the degree of health maintained as well as the extent and timing of related recurrences and consequences” In this tier, the first dimension considers the recurrence of disease or long-term complications, whereas the second dimension captures new health conditions that occur as a consequence of treatment.

In this 3-tiered outcome model, improving 1 dimension benefits the others, and tradeoffs among outcome measures can be explicitly considered. For example, although there are limited treatment options for some metastatic cancers that do not influence survival (tier 1, first dimension) but may provide timely care, palliation of symptoms, and prolonged time to adverse consequences, thereby positively affecting tier 2 and tier 3 dimensions. An example of the hierarchical outcome model as applied for patients with locally advanced extremity soft tissue sarcoma is shown in Fig. 2 .