Bacterial vaginosis

Trichomonas vaginalis

Vaginitis

Vulvovaginal candidiasis

History: It should include type, duration, and extent of symptoms (i.e., discharge, pruritus, odor, dyspareunia, dysuria, rash, pain); relation of symptoms to menses; frequency and type of sexual activity, and number of sexual partners; previous STIs; contraceptive history; medications, especially antibiotics and steroids; use of deodorants, soaps, lubricants, or douches; and history of immunosuppression.

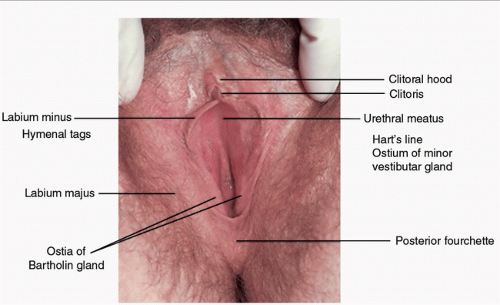

Examination: It should include inspection of color, texture, origin (vaginal or cervical), adherence, and odor of the vaginal discharge; inspection of the perineum, vulva, vagina, and cervix for erythema, swelling, lesions, atrophy, trauma, and foreign bodies; and palpation of the introitus, uterus, and adnexa for tenderness or masses (Fig. 51.1).

Laboratory:

The pH value of vaginal secretions is sampled from the anterior vaginal fornix or lateral vaginal wall. Cervical mucosa should not be sampled due to its higher pH of approximately 7.0.

A saline wet mount should be examined under dry high power. Normal findings include <5 to 10 WBCs per high-power field or ≤1 WBC per epithelial cell, as well as lactobacilli. Abnormal findings include presence of “clue cells” (Fig. 51.2), defined as epithelial cells covered with bacteria and demonstrating indistinct borders and intracellular debris, as well as trichomonads. Motility of trichomonads decreases with time; thus, immediate inspection of wet mount is advised.

A potassium hydroxide (KOH) slide should be prepared, and an immediate fishy, amine odor is called a positive “whiff test” and is suggestive of BV. Under dry high power, abnormal findings are yeast buds and pseudohyphae.

Rapid or point-of-care tests (POCTs) for TV, VVC, and BV should be considered particularly when microscopy is not available in the office setting.

In women with discharge, testing for C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae is advised.

FIGURE 51.1 Normal vulva. (From Edwards L, Lynch PJ. Genital dermatology atlas. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2010.) |

Prevalence: Data show an overall prevalence of the disease of 29%; among those 14 to 19 years old the prevalence is 23%, and among those 20 to 29 years old the prevalence increases to 31%.3

Transmission: There continues to be controversy about the possibility of BV being transmitted sexually. Although BV has a higher prevalence among sexually active AYAs, it can also be found in females who are not sexually active. In addition, while the use of condoms seems to be a protective factor, treatment of partners does not prevent reoccurrence of the disease process.2

TABLE 51.1 Vaginal Discharge in the AYAs

Condition

Signs and Symptoms

Diagnosis in the Office Setting

Physiologic discharge

Clear gray discharge, no offensive odor, no burning or itching

Wet prep: Epithelial cells with no or few polymorphonuclear cells; no pathogens

Vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC)

Curd-like discharge, intense burning, pruritus, usually no odor, often associated vulvitis

KOH/wet prep: budding yeast and pseudohyphae

Trichomoniasis

Pruritus; malodorous, frothy, yellow-green discharge; dysuria; rarely, abdominal pain

Wet prep: pear-shaped organism with motile flagella, point-of-care test

Bacterial Vaginosis (BV)

Homogenous, malodorous, gray-white discharge; usually mild or no pruritus or burning

Wet prep: epithelial cells covered with gram-negative rods, few polymorphonuclear leukocytes, pH >4.5

Retained tampon

Malodorous discharge, local discomfort

History and physical examination, history of exposure to deodorant spray or scented tampons

Irritant vaginitis

Vaginal discharge, erythema

History and physical examination

Predisposing factors: BV is associated with Black race/ethnicity, increased frequency of douching, cigarette smoking, and increased number of lifetime sex partners.3

Presentation: Up to 50% of cases are asymptomatic. Symptoms include vaginal pruritus and discharge, more noticeable after intercourse or after menses. The discharge is classically homogeneous, thin, and grayish-white, with a “fishy” odor.2

Examination may reveal the typical discharge adhering to the vaginal walls and odor.

Complications: BV is linked to serious sequelae including pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), increased human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) acquisition and transmission, infertility, and postsurgical/postabortal infection. Obstetric complications include chorioamnionitis, premature rupture of membranes, preterm labor, postpartum endometritis, and postabortal infection.2

The Amsel criteria are used for clinical diagnosis. Three of the four clinical symptoms and signs are required: (1) homogeneous, grayish-white discharge; (2) vaginal pH level >4.5; (3) positive whiff test; and (4) wet prep showing “clue cells,” that comprise at least 20% of the epithelial cells.2

Commercial tests are available including Affirm VP III, an automated DNA probe assay for detecting G. vaginalis;4 OSOM BVBlue (Sekisui Diagnostics), a 10-minute Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)-waived chromogenic diagnostic test based on the presence of elevated sialidase enzyme activity, which is produced by bacterial pathogens including Gardnerella;5 and Pip Activity TestCard (Quidel Corporation), a proline-aminopeptidase that detects proline iminopeptidase (PIP) activity found with G. vaginalis and Mobiluncus spp.6 Sensitivities and specificities for these test are 95% / 100%, 90.3% / 96.6%, and 91.6% / 97.67%, respectively, compared to Gram stain and/or the Amsel criteria.4,5,6

For nonpregnant patients, recommended regimens are metronidazole 500-mg oral tablet twice daily for 7 days, metronidazole 0.75% gel 5 g intravaginally once daily for 5 days, or clindamycin 2% cream 5 g intravaginally daily for 7 days. Cure rates for all these regimens are 75% to 85%. Alternative treatments include tinidazole and oral clindamycin regimens. Please see the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]7 guidelines for the most updated information (www.cdc.gov). Patients should be warned to avoid ingestion of alcohol within 3 days of taking oral metronidazole because of the possibility of disulfiram-like reaction with nausea, vomiting, and flushing. In addition, clindamycin cream is oil based and might weaken latex condoms and diaphragms for 5 days after use.

Recurrent BV occurs in 20% to 30% of cases within 3 months. The treatment recommended by the CDC7 is an initial 7-day course of oral or intravaginal metronidazole or clindamycin. For reoccurrence, re-treatment with the same regimen and use of a different treatment regimen are both acceptable. Suppression therapy then follows with a 4- to 6-month course of metronidazole gel twice a week.7

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree