Urticaria and Angioedema

Jeffrey R. Stokes

Mark H. Moss

INTRODUCTION

Urticaria and angioedema are both symptoms and signs of specific diseases and independent disease classifications in their own right. For example, urticaria can be a sign of anaphylaxis when associated with signs and symptoms in other organ systems such as wheezing or hypotension. As a result, these diseases tend to be difficult to characterize by clinicians and patients alike resulting in confusion. Patients seek to have a definitive cause of their “hives,” “whelps,” or “welts” identified so that they can avoid and eliminate the trigger. Clinicians seek to identify or rule out known triggers to characterize urticaria and angioedema with a specific cause or to move on to classify the disease as idiopathic.

I. PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Urticaria is caused by dilation of small venules and capillaries in the superficial dermis. The cutaneous mast cell is the primary cell involved in urticaria pathology. Classically, an antigen binds to high-affinity IgE receptors on the mast cell leading to the immediate release of mediators, such as histamine, prostaglandins, leukotrienes, and tryptase. A late inflammatory reaction occurs several hours after mast cell activation, leading to an increase in eosinophils, neutrophils, lymphocytes, and basophils at the site. The preformed mediator histamine is largely responsible for the classic wheal along with the flare response of vasodilation (erythema), increased vascular permeability (edema), and the axon reflex that increases this reaction via the neurotransmitter substance P. Substance P is a potent vasodilator that can stimulate further histamine release. Prostaglandin D2 is another vasodilator, while the cysteinyl leukotrienes, LTC4 and LTD4, increase vascular leakage and edema. All skin surfaces can be equally affected although urticaria can be more common on warmer body surfaces or areas compressed by clothing. Angioedema involves a similar mechanism but occurs in the deep dermis and subcutaneous tissue.

II. ACUTE/CHRONIC URTICARIA

A. Definition

Acute urticaria/angioedema lasts for <6 weeks, while chronic lasts 6 weeks or longer; however, some classification systems use 8 weeks as the cutoff between acute and chronic disease. Acute urticaria and angioedema are more frequently associated with identifiable causes, while chronic urticaria/angioedema is more often associated with physical urticarias, presence of autoantibodies, or lack of an identifiable cause. Descriptive features of

urticaria include a rash that is erythematous, raised, pruritic, blanchable, and generally transient with individual lesions lasting <24 hours. Chronic angioedema without urticaria may be hereditary, acquired, or idiopathic and will be discussed separately.

urticaria include a rash that is erythematous, raised, pruritic, blanchable, and generally transient with individual lesions lasting <24 hours. Chronic angioedema without urticaria may be hereditary, acquired, or idiopathic and will be discussed separately.

B. Acute urticaria

1. Background

Acute urticaria is the most likely form of the disease to occur in pediatric patients and is often associated with recent viral infection or medication use. Acute urticaria occurs in as many as 15% to 24% of the US population at some point during their lifetime. Men and women are equally affected by acute urticaria, and all age groups are affected. Urticarial lesions are intensely pruritic and may be accompanied by angioedema in as many as 50% of patients. Patients often present to the emergency room or urgent/immediate care clinics due to the intense discomfort caused by the pruritus. Acute urticaria is self-limited lasting days to weeks. Although it lacks long-term consequences, urticaria is uncomfortable and significantly affects quality of life, causing anxiety and depression, and is frequently associated with sleep disturbance.

2. Causes

The most important information in identifying a cause of acute urticaria is a thorough history of the events occurring immediately preceding the appearance of the initial symptoms. Identifiable causes include foods; medications; insect stings; infections; contact with allergens such as latex, animals, and plants; and physical causes (Table 12-1).

a. Foods

Readily identifiable exposure to foods should be explored in cases of acute urticaria where the patient or their family implicate a suspected food. This is in contrast to chronic urticaria where foods are much less frequently identified as a causative agent. The most common foods associated with urticaria in children are milk, eggs, peanut, soy, wheat, fish, and tree nuts and in adults are peanut, tree nuts, fish, and shellfish. The clinician should try to establish a temporal relationship between the suspected food and the onset of the urticaria. Usually, if a food is causative, the urticarial eruption will

occur within 15 to 120 minutes of ingestion of the food, rarely hours later, and not on the following day. This temporal association should be reproducible upon reexposure to the suspect food. The history should guide very focused testing using a single food or small number of foods by skin prick testing (SPT) or blood immunoassay testing (RAST or CAP-FEIA) for food-specific IgE antibodies.

occur within 15 to 120 minutes of ingestion of the food, rarely hours later, and not on the following day. This temporal association should be reproducible upon reexposure to the suspect food. The history should guide very focused testing using a single food or small number of foods by skin prick testing (SPT) or blood immunoassay testing (RAST or CAP-FEIA) for food-specific IgE antibodies.

Table 12-1 Common Causes of Acute Urticaria and Angioedema | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

b. Medications

Medications cause numerous and varied reactions that may or may not be associated with cutaneous findings. Urticaria is a frequent side effect associated with most medications but is most frequently encountered with antibiotics, typically in the beta-lactam family, and opiates. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSIADs), classically aspirin, can cause (or worsen) urticaria, although the specific mechanism is variable including both non-IgE and possibly IgE-related mechanisms. Latex has also been associated with acute contact urticarial responses. A detailed medication history including start and stop dates is essential as temporal cessation of a medication is often associated with urticaria resolution and reintroduction with a recurrence. However, drugs causing serum sickness can result in urticarial eruptions well after discontinuation. Specific questioning about over-the-counter medications such as aspirin or other NSAIDs is essential as patients typically do not mention them unless asked directly. Urticaria frequently, but not always, occurs shortly after a medication is initiated.

i. ACE inhibitors (Angiotensin-converting enzyme)

ACE inhibitors can cause urticaria but are most often associated with acute onset of potentially life-threatening angioedema within the first month of therapy. However, ACE inhibitor-associated angioedema can occur after months or even years of therapy. The angioedema associated with ACE inhibitors is likely due to impaired degradation of bradykinin typically leading to swelling of the face and tongue but can involve other areas. Most patients who have experienced ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema can safely use angiotensin receptor blockers without an increased risk of angioedema.

c. Infections

Infections are frequent causes of acute urticaria in children (usually a virus) and, to a lesser degree, adults. Urticaria may occur as part of a viral prodrome; however, it more often occurs or persists after the clinical infection has resolved, theoretically as part of a lingering immune response. Mycoplasma has been linked to acute urticaria but can progress to erythema multiforme. Case reports of localized bacterial infections in the sinuses, the lungs, and the prostate and dental abscesses have been associated with acute urticaria, but work-ups for unsuspected infections are unwarranted. Parasitic infection should be pursued as a possible cause when there is associated travel to endemic regions or exposure history. Fungal infections, including yeast, have been associated with acute urticaria, but again, this is a rare cause. Overall, if an infection is found, it is best to treat it, but this may not affect the urticaria.

d. Comorbid conditions

Autoimmune, lymphoproliferative, and endocrine disorders may also be associated with acute urticaria, although they are more likely associated with chronic urticaria. Papular urticaria of pregnancy (i.e., pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy or PUPPs) is a self-limiting inflammatory condition seen in various stages of pregnancy presenting as an urticarial-like rash. It should also be noted that many patients with acute urticaria also have a component of physical urticaria and develop intensification of lesions at sites of constriction from clothing, with increased body temperature, heat exposure, or emotional distress.

C. Chronic urticaria

1. Background and definition

Patients with chronic urticaria have symptoms for more than 6 weeks. It is more likely to occur in adult patients but can occur in any age group. In general, the longer that the urticaria has been present, the less likely it is that a specific trigger will be identified. Chronic urticaria occurs in approximately 1% of the US population during their lifetime. Women are twice as likely to be affected. Urticarial lesions are intensely pruritic and may be accompanied by angioedema in as many as 50% of patients. Although chronic urticaria also lacks long-term consequences, it significantly affects quality of life affecting activities of daily living, social interactions, work, and sleep. Much like acute urticaria, the lesions of chronic urticaria can occur almost anywhere on the skin. While chronic urticaria can remit spontaneously with as many as 50% of patients finding resolution after 1 year, up to 20% of patients will continue to have urticaria for 10 years or longer.

2. Identifiable causes include autoimmune responses/diseases and physical triggers (Table 12-2). However, as much as 80% of chronic urticaria is idiopathic, without a definable cause. Seldom are acute viral illness,

foods, medications, or other allergens triggers for chronic urticaria in contrast to acute urticaria.

foods, medications, or other allergens triggers for chronic urticaria in contrast to acute urticaria.

Table 12-2 Causes of Chronic Urticaria | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

a. Autoimmune

i. Classic autoimmune diseases such as SLE, Still’s disease, Sjögren’s syndrome, and dermatomyositis can present initially with urticaria. Patients with urticarial vasculitis may have associated JRA (juvenille rheumatoid arthritis), SLE (systemic lupus erythematosus), or hepatitis B or C. These patients usually present with lesions lasting more than 24 hours, and the individual lesions can be painful instead of pruritic.

b. Physical urticarias

Physical triggers cause 10% to 20% of chronic urticaria. These include dermatographic, cholinergic, cold-associated, aquagenic, solar, vibratory, and delayed pressure urticaria (Table 12-2). These physical factors may aggravate both acute and chronic urticaria or may be the primary cause of chronic urticaria.

i. Dermatographic

Dermatographism, or dermatographic urticaria, is the development of an urticarial wheal at the site of physical pressure on the skin from scratching the skin or from tight clothing. This most common form of chronic urticaria affects between 4% and 5% of the general population. As a result of firmly stroking the skin, wheal-and-flare response develops. In comparison to other forms of urticaria, it is generally less pruritic.

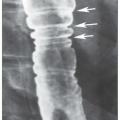

ii. Cholinergic

Cholinergic urticaria is the development of small urticarial wheals (classically 1 to 3 mm in diameter) surrounded by large flares typically as a result of increased body temperature from physical activity. Cholinergic urticaria may account for up to 5% of all cases of chronic urticaria. Specific triggers often include hot baths and showers, exercise, sweating, and rarely anxiety. Cholinergic urticaria can range from being mildly pruritic and nonbothersome to life-threatening with systemic signs of anaphylaxis. Provocative testing includes exercise, hot water immersion, or a methacholine intracutaneous challenge test, although the negative predictive value of these tests is variable.

iii. Cold-induced (acquired and familial)

Cold-induced urticaria syndromes are characterized by the development of urticaria or angioedema following exposure to cold temperature. Although these conditions are generally benign, there are several instances reported of shock-like reactions during sudden immersion in cold water. Laryngeal edema has been reported after drinking cold beverages or eating cold food such as ice cream. Primary cold-induced urticaria is usually acquired, although there is a rare familial form. Patients with familial delayed cold urticaria develop urticarial lesions 9 to 18 hours after cold exposure, which then resolve as hyperpigmented skin lesions. Family studies suggest an autosomal dominant inheritance. Familial cold autoinflammatory syndromes are distinct diseases and have nonurticarial rashes. Systemic disorders should be considered as potential causes for secondary cold-induced urticaria including cryoglobulinemia,

mycoplasma infection, infectious mononucleosis, or vasculitis. Diagnostic testing for acquired disease is performed using the ice cube test. An ice cube or chip in a plastic bag is placed on the skin of the forearm for 5 minutes. During rewarming of the skin, erythema develops first and is followed by urticaria formation.

mycoplasma infection, infectious mononucleosis, or vasculitis. Diagnostic testing for acquired disease is performed using the ice cube test. An ice cube or chip in a plastic bag is placed on the skin of the forearm for 5 minutes. During rewarming of the skin, erythema develops first and is followed by urticaria formation.

iv. Aquagenic

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree