Adrian S. Wagg There is an often used quote stating that the bladder is an unreliable witness and the symptoms a patient describes do not point to the true pathology.1 This belief has arisen from the assumption that patients can be fitted into clearly separate diagnostic categories, in which a set of unique symptoms leads to distinct diagnoses. Given that there is likely to be a spectrum of disease, reflecting the variability inherent in any biologic system, diagnostic categories most likely form intersecting continua that share symptoms. Epidemiologic surveys have revealed this complex coexistence of lower urinary tract symptoms. The bladder detrusor muscle has a relatively limited repertoire with which to respond to any number of insults (e.g., ischemia, obstruction, diabetes mellitus, aging). Essentially, it can become overactive or fail. There is mounting evidence from human studies that there is a transition from one state to the other over time, which also accounts for the occurrence of bladder overactivity and impaired emptying in the same individual.2 The great majority of symptoms can be explained by the physiologic and mechanical principles that govern the lower urinary tract and its interplay with the central nervous system—what patients say usually makes sense. Experimental data have supported this thesis,3 but there is a continual search for classification, discrimination, and scoring of disease variables, which largely leads to greater understanding of disease or advances in treatment. This chapter examines the prevalence, assessment, and management of urinary incontinence (UI) and troublesome lower urinary tract symptoms in older adults, both robust and frail. For frail older adults, this take into account their remaining life expectancy and expectations, as well as those of their caregivers, for the treatment and amelioration of UI. Although incontinence is a common symptom of later life, it is not an inevitable consequence of aging. UI has a demonstrable negative impact on quality of life, leading to social isolation and deconditioning.4–7 Incontinence is also associated with various adverse consequences, including falls and fractures, skin infections, functional impairment, and depression.8–11 UI is also an independent predictor of institutionalization.12,13 The per capita cost of incontinence increases with age, with many of the expenses attributable to the costs of absorbent products and nursing home care.14,15 Urinary urgency is the hallmark symptom of overactive bladder (OAB), which for approximately one third of the population is associated with UI.5 The prevalence and incidence of urgency and urgency incontinence increase in association with aging. In the EPIC (European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition) study of adults older than 40 years (based on structured telephone interviews of over 19,000 people from four European countries and Canada), 19.1% of community-dwelling men (95% confidence index [CI], 17.5 to 20.7) and 18.3% of women older than 60 years (95% CI, 16.9 to 19.6) indicated that they had urinary urgency and 2.5% of men (95% CI, 1.9 to 3.1) and 2.5% of women (95% CI, 1.9 to 3.0) indicated that they had urgency incontinence.4 Similarly, in the NOBLE study, a population-based U.S. survey of 5,204 adults, the overall prevalence of OAB was 16% in men and 16.9% in women, increasing in association with age.6 More recently, reports from longitudinal studies in cohorts of men and women have illustrated the age-related increase in lower urinary tract symptoms, including urgency and urgency incontinence over time. In one study of women, 2,911 responded to a self-administered questionnaire in 1991; of these women, 1,408 replied to the same questionnaire in 2007. Over that time, the prevalence of UI, OAB, and nocturia increased by 13%, 9%, and 20% respectively. The proportion of women with OAB and urgency incontinence increased from 6% to 16%.16 In a similar study of men,17 7,763 responded to a self-completed questionnaire in 1992, and 3,257 responded again in 2009. In a similar fashion as in women, the prevalence of UI and OAB increased in the men assessed in 1992 and 2003 (overall UI, from 4.5% to 10.5%; OAB, from 15.6% to 44.4%). The prevalence of nocturia, urgency, slow stream, hesitancy, incomplete emptying, postmicturition dribble, and daytime frequency also increased. Only a minority of men, as opposed to a considerable proportion of women, reported any regression of symptoms, although the limitations of regression in the context of epidemiologic survey time frames need to be taken into account. Stress urinary incontinence (SUI), urinary loss that occurs on exertion or effort, appears to have its peak incidence in women in midlife. In the EPIC study,4 3.7% of women younger than 39 years (95% CI, 3.1 to 4.3) and 8.0% of women older than 60 years (95% CI, 8.1 to 9.0) had the condition. In men, most SUI occurs following prostate surgery, with rates varying depending on the type of operation. Transurethral resection of the prostate is associated with rates of approximately 1%,18 whereas retropubic radical prostatectomy is associated with higher rates, from 2% to 57%.19,20 Some of this variation, however, is explained by differences in the definition used, date of the report, time of ascertainment of SUI following surgery, and population surveyed; however, the proportion of men with SUI is generally most prevalent in the oldest groups. The EPIC study has revealed a prevalence of 0.1% (95% CI, 0.0 to 0.2) in those younger than 39 years and 5.2% (95% CI, 4.2 to 6.1) in those older than 60 years. According to current evidence, if a woman describes stress incontinence, there is a 78% probability that sphincter dysfunction exists. Although there is a reduction in the maximum closing pressure that can be generated in the urethra in association with increasing age, this closing pressure must exceed the pressure of urine at the bladder neck for continence to be maintained. As the bladder fills, a pressure will develop equal to the hydrostatic pressure of urine in the bladder plus the weight of any viscera pressing on it. If the maximum urethral closure pressure is reduced below this, the woman will develop a sense of impending incontinence, because the hydrostatic pressure rises with positional changes, which typically exacerbates this. The woman will thus be forced to maintain a bladder capacity below the threshold. Frequency, urgency, and urgency incontinence may all therefore be induced by an incompetent urethral sphincter. Additionally, rising during or at the end of the night, with a full bladder and suddenly applying an increased hydrostatic pressure to the bladder neck and faulty sphincter will lead to very severe urgency and precipitancy. Mixed symptoms—that is, urinary incontinence with symptoms of urinary urgency incontinence and exertional incontinence—are highly prevalent in primary care.21 Urodynamic studies of women with mixed symptoms have predominantly identified only urodynamic stress incontinence, although to what extent this reflects the imprecision of urodynamic testing is unclear. Some epidemiologic data have suggested that mixed incontinence accounts for approximately one third of all cases of incontinence in women, but age in the EPIC study of mixed UI only accounted for 4.1% of incontinence in women older than 60 years, probably highlighting the difficulty with the operational definition.4,22 It is not uncommon to find a postvoid residual volume of urine in older adults. In one survey of community-dwelling men and women older than 75 years, more than 10 mL of residual urine was found in 91 of the 92 men (median, 90 mL; range 10 to 1502 mL) and in 44 of the 48 women (median, 45 mL; range 0 to 180 mL).23 In a study of men undergoing a urologic workup, a postvoid residual volume more than 50 mL was 2.5 times greater for men with a prostate volume greater than 30 mL than in men with smaller prostates. The postvoid residual was not associated with the American Urological Association symptom index score (now International Prostate Symptom Score), age, or peak urinary flow rate. Men with a postvoid residual greater than 50 mL were about three times as likely to have subsequent acute urinary retention with catheterization during the subsequent 3 to 4 years and, in another study, a residual volume more than 300 mL predicted the need for invasive therapy over a similar time period.24,25 Another study in older women found a residual volume of 100 mL or more in up to 10% of older women, many of whom were asymptomatic. It appeared that the residual volume remitted over a 2-year period.26 The clinical irrelevance of a small residual volume is clear, but the extent to which residuals may vary from void to void, and the natural history of ineffective voiding in older persons, are less clear, although what constitutes a normal or acceptable postvoid residual urine in older adults is still widely debated. The widely held concerns about recurrent urinary tract infection, incontinence, and upper renal tract damage are not well substantiated in otherwise normal older adults. Whereas nocturia is extremely common in older adults, nocturnal enuresis (NE) is less so in community-dwelling older adults. In a study of 3884 community-dwelling men and women 65 to 79 years of age, it was reported by 2.1% and was significantly higher among women (2.9%) compared with men.27 NE occurred in 35% (495 of 1429) residents older than 65 years in nursing homes sampled as part of a national audit of continence care from England and Wales. In 2010, the reported prevalence in the same setting was 43% (477 of 1097).28–30 It is often accompanied by other associated lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and is complicated by comorbid conditions or the effects of medications affecting sleep. Congestive heart failure, functional disability, depression, use of hypnotics at least once weekly, and nocturnal polyuria have been associated with the condition, and the persistence of childhood nocturnal enuresis into adulthood has been well described. Adult-onset NE without daytime symptoms in an older person without significant comorbidity is a serious symptom that usually signifies significant urologic pathology and should be thoroughly investigated.31,32 Unfortunately, there is little available evidence on which to guide the management of older adults in any setting, from acute care to nursing home resident. Older studies that have addressed the problem describe punitive interventions, which would by today’s standards never be ethically approved.33 Urinary incontinence in older adults may be wholly unrelated to lower urinary tract dysfunction. Successful toileting requires sufficient cognition and physical function, including manual dexterity, to reach the toilet, undress, and void in a timely and socially appropriate fashion. For many frail older adults, the burden of physical or cognitive impairment renders this less likely. Incontinence in these situations is termed functional incontinence. There is little systematic evaluation or assessment of the prevalence or management of this clinical entity; much of what is practiced is a result of received wisdom involving behavioral and conservative techniques used for the general management of incontinence in frail older adults (see later). Much data are derived from older men and women with LUTS, often without comparative controls. In more recent studies, people with LUTS have been compared across all age groups.34–37 Of the potential subtypes of urinary incontinence, urgency incontinence appears to be the most common cause in older adults. Among outpatients presenting with lower urinary tract symptoms, between 75% and 85% of women and 85% to 95% of men aged 75 years and older will be found to have detrusor overactivity.38 The observed changes associated with older age in men and women with LUTS undergoing cystometry are listed in Box 106-1. In men, the influence of the enlarging prostate on the outflow tract appears to dominate the evolution of bladder physiology. In older men and women, detrusor overactivity is associated with lower bladder capacities than in those with normal bladders. Older adults void less successfully in late life, and voiding is associated with higher residual urine volumes. The explanations for this are probably complex. There is evidence for a reduced speed of detrusor shortening as well as problems in sustaining adequate voiding contractions.36,39 The transmission of force from the detrusor is dampened by the accumulation of collagen and connective tissue, giving the impression of impaired contractility, a common misnomer. The combination of detrusor overactivity and incomplete bladder emptying in older adults is commonly found in combination. Detrusor hyperactivity and impaired contractile function (DHIC) were described as involuntary detrusor contractions, postmicturition residual urine volume, and reduced speed and amplitude of isometric detrusor contractions.40 Elbadawi and colleagues41 performed electron microscopy studies of bladder biopsy specimens from older men (n = 11) and older women (n = 24); they reported four structural patterns precisely matching four urodynamic groups, with no overlap. However, these findings have not been corroborated; Carey and associates42 reported finding some of the defining histologic characteristics described by Elbadawi’s group evenly distributed between normal women (n = 15) and women with detrusor overactivity (n = 22). In vitro studies of detrusor muscle contraction have revealed a lower level of acetylcholine release in association with increasing age.43 There are also data showing a reduction in the number of acetylcholinesterase-containing nerves within the muscle.44 There are also changes in urethral function. Older age is associated with lower values of the pressures at which urine begins and stops flowing, even in the presence of detrusor overactivity. Data from studies measuring the maximum urethral closure pressure have also shown a similar decline in association with increasing age. Histologically, there is evidence of an age-related apoptosis of striated muscle cells of the urethral sphincter.45,46 The combination of reduced bladder capacity, increased urinary frequency, impaired bladder sensation, and the central mechanisms discussed next means that an older person has less time than a younger person to respond to a full bladder, explaining the commonly expressed complaint of older adults that “when they have to go, they have to go.” There is a known association between vascular risk factors and LUTS.47 The presence of white matter hyperdensities within periventricular and subcortical regions of the brain are associated with functional and cognitive impairment, increased incidence of urinary urgency and detrusor overactivity on cystometry, and difficulty in maintaining continence.48,49 There is also accumulating evidence that the frontal regions of the older person’s brain “work harder” to suppress urinary urgency than that of a younger person. This in turn suggests that the micturition center in the pons might be normally “on” but continually suppressed, rather than a simple “on-off” switch, as has hitherto been thought. Many people with UI will have at least one coexisting chronic medical condition; many of these are associated with the development or worsening of UI, or their presence may make successful continent toileting more difficult. In a large population-based observation study, UI (defined as the use of pads) was increasingly associated with the existence of other geriatric conditions (e.g., cognitive impairment, injurious falls, dizziness, vision impairment, hearing impairment)—one condition in 60% of those studied, two or more conditions in 29%, and three or more in 13%.50 The impact of other chronic diseases has not been as well evaluated, but conditions such as peripheral vascular disease, Parkinson disease (PD), diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, venous insufficiency and chronic lung disease, falls and contractures, recurrent infection, and constipation have all been implicated as exacerbating factors. Similarly, hypertension, congestive heart failure, arthritis, depression, and anxiety have all been associated with a higher prevalence of UI. In one study, a linear relationship was demonstrated between the prevalence of UI and number of comorbid conditions. (correlation coefficient = 0.81).51 Comorbid conditions can affect incontinence through a number of mechanisms. For example, diabetes mellitus, present in approximately 15% to 20% of older adults, may cause UI by diabetes-associated LUT dysfunction (e.g., DO, OAB, cystopathy, incomplete bladder emptying), or by poor diabetic control (e.g., hyperglycemia causing osmotic diuresis and polyuria). The Nurses Health Studies has shown an increase in weekly urgency incontinence (odds ratio [OR], 1.4) in women with type 2 diabetes compared to those without. Findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2001-2002 survey showed that the prevalence of UI is significantly higher in women with impaired fasting glucose levels and diabetes mellitus compared to those with normal fasting glucose levels. Two microvascular complications caused by diabetes, peripheral neuropathic pain and microalbuminuria, were associated with weekly UI.52 Table 106-1 lists common conditions associated with UI in older adults. There are studies on interventions only for PD, obstructive sleep apnea, and obesity. Data from nursing home residents have suggested that older adults with incontinence are more significantly burdened by multimorbidity than those without.53 TABLE 106-1 Comorbid Conditions That Can Cause or Contribute to Urinary Incontinence in Frail Older Adults Congestive heart failure Lower extremity venous insufficiency Appropriate use of stool softeners Adequate fluid intake and exercise Disimpaction if necessary UI after acute stroke often resolves with rehabilitation; persistent UI should be further evaluated. Regular toileting assistance essential for those with persistent mobility impairment Optimizing management may improve mobility, improve UI Regular toileting assistance essential for those with mobility and cognitive impairment in late stages Inaccessible toilets Unsafe toilet facilities No contrasting color between toilet and seat Caregivers unavailable for toileting assistance The likelihood of incontinence increases in association with the severity of dementia but older longitudinal studies did not identify an association with incident cases.54,55 Another more recent longitudinal study of 6,349 community-dwelling women has found that a decrease in mental functioning, as measured by a modified Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) score, was not associated with increased frequency of urinary incontinence over 6 years, but did predict a greater impact of the condition.56 Despite strong associations with baseline incontinence in the Canadian Study of Health and Aging, moderate or severe cognitive impairment measured using the modified MMSE was not associated with incident UI over 10 years.57 However, in a longitudinal study of 12,432 women aged 70 to 75 years, with a 3-year follow-up, there was a strong association with a dementia diagnosis (OR, 2.34).58 Similarly, over a 9-year follow-up of 1,453 women aged 65 years, dementia was strongly associated with incident UI (relative risk [RR], 3.0).13 Likewise, in a Scottish study, the prevalence of UI increased with decreasing MMSE scores and was notably more common in those with impairments of attention and orientation, verbal fluency, agitation, and disinhibition.59 Incontinence in dementia adds to caregiver burden60 and influences decisions to relocate people to nursing homes.13 It is unknown whether successful management of incontinence can reduce this associated burden or alter nursing home decisions, because the evidence is limited to case reports and anecdotes. Incontinence is associated with a reduced quality of life and impaired nutrition and mobility in older adults with dementia,61,62 but is sadly neglected in terms of the amount of attention paid to it, despite the acknowledged adverse effects on quality of life and associated costs of management.63 In England and Wales, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) quality standard for UI has noted that active treatment is better than containment.64 A dementia diagnosis should not preclude an attempt to manage incontinence with behavioral methods, but for those with a compromised ability to learn behavioral change, this is clearly inappropriate. A stepwise approach to initiating interventions and assessing the results seems like a reasonable first step in management. Some medications may predispose older adults to incontinence. Wherever possible, they should be reviewed and, if possible, any offending drugs should be removed or the dose reduced. Evidence exists for diuretics, calcium channel blockers, prostaglandin inhibitors, α-blockers, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, cholinesterase inhibitors, and systemic hormone replacement therapy,65–72 but the list is more extensive due to the potential of adverse effects of some drug classes to affect continence status (Table 106-2). Cholinesterase inhibitors for dementia are of particular relevance because their use appears to be associated with an increased risk of urinary urgency and urgency incontinence.73 Older nursing home residents with dementia newly treated with cholinesterase inhibitors are more likely to be prescribed a bladder antimuscarinic than those with dementia.74 Treatment with bladder antimuscarinics in addition to cholinesterase inhibitors has not been associated with delirium but, in one study, a decrease in the ability to carry out the activities of daily living (ADLs) in the most functionally independent people at baseline was noted.75 TABLE 106-2 Medications That Can Cause or Contribute to Urinary Incontinence in Frail Older Adults Psychotropic drugs Sedatives Hypnotics Antipsychotics Histamine1 receptor antagonists In a study of trospium and galantamine co-prescription, no effect on cognition or ADLs and some benefits on continence-related outcomes were found.76,77 The current weight of evidence, albeit of low quality, appears to be that a positive outcome in terms of bladder control can be achieved without a significant detriment in cognition or ADLs. Currently, there are no data on quality of life outcomes for this group of older adults who are treated with this combination of agents. Obviously, there needs to be due consideration about the risks and benefits of treatment with either agent before taking any action. In line with current recommendations, a screening question about bladder and bowel problems should be asked as part of all health care interactions between an older person and clinician.78 A simple question such as “Do you have any problems with bladder or bowel function?” is usually recommended. If the answer to that question is positive, an assessment should be offered. There has been little systematic evaluation of the utility of components of the clinical assessment in older adults. Generally, the traditional biomedical model of history taking and examination has been applied. In England and Wales, the national guidelines for LUTS in men suggest that the following be carried out: (1) general medical history to identify possible causes and comorbidities; (2) review of medications that may be contributing to the problem; (3) physical examination guided by symptoms and other medical conditions; (4) examination of the abdomen and external genitalia; and (5) digital rectal examination and urine dipstick test to detect blood, glucose, protein, leukocytes, and nitrites. The guidelines for women are a variation on these.79,80 In the United States, data have suggested that primary care practitioners fail to follow the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality UI guidelines (now obsolete), and nursing home practitioners rarely follow federal guidelines for UI care regarding recommended physical examination, postvoid residual volume (PVR) testing, urinalysis, and identification of potentially reversible causes.81 Okamura and colleagues have investigated the diagnosis and treatment of LUTS by general practitioners and found adherence to the guidelines, reinforced by educational and promotional activities, resulted in better treatment outcomes.82,83 Although it is unusual for guidelines to consider multimorbidity, the International Consultation on Incontinence does include guidance on the assessment and management of fecal and urinary incontinence in frail older adults.78 Older cognitively impaired people are less able to cooperate in lifestyle interventions for their incontinence and may also be at risk of developing further impaired cognition in response to high-dose antimuscarinic therapy or high preexisting antimuscarinic burden.84 However, the actual occurrence of this is rare in community-dwelling older adults, and studies have suggested that it is only those at the highest levels of exposure who might be affected. The modified MMSE does not appear to be sensitive enough to detect the magnitude of change associated with the bladder antimuscarinics and the results of other tests, such as the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, are not known. The best that might be achieved is an overall assessment of global thought processes and everyday decision making by the older adult or family member or caregiver.

Urinary Incontinence

Introduction

Impact of Incontinence

Urinary Urgency and Urgency Incontinence

Underlying Causes of Urinary Incontinence

Stress Urinary Incontinence

Mixed Urinary Incontinence

Voiding Inefficiency

Nocturnal Enuresis

Functional Incontinence

Physiologic Changes in Lower Urinary Tract Function Associated with Aging

Central Mechanisms of Urinary Urgency

Associated Factors

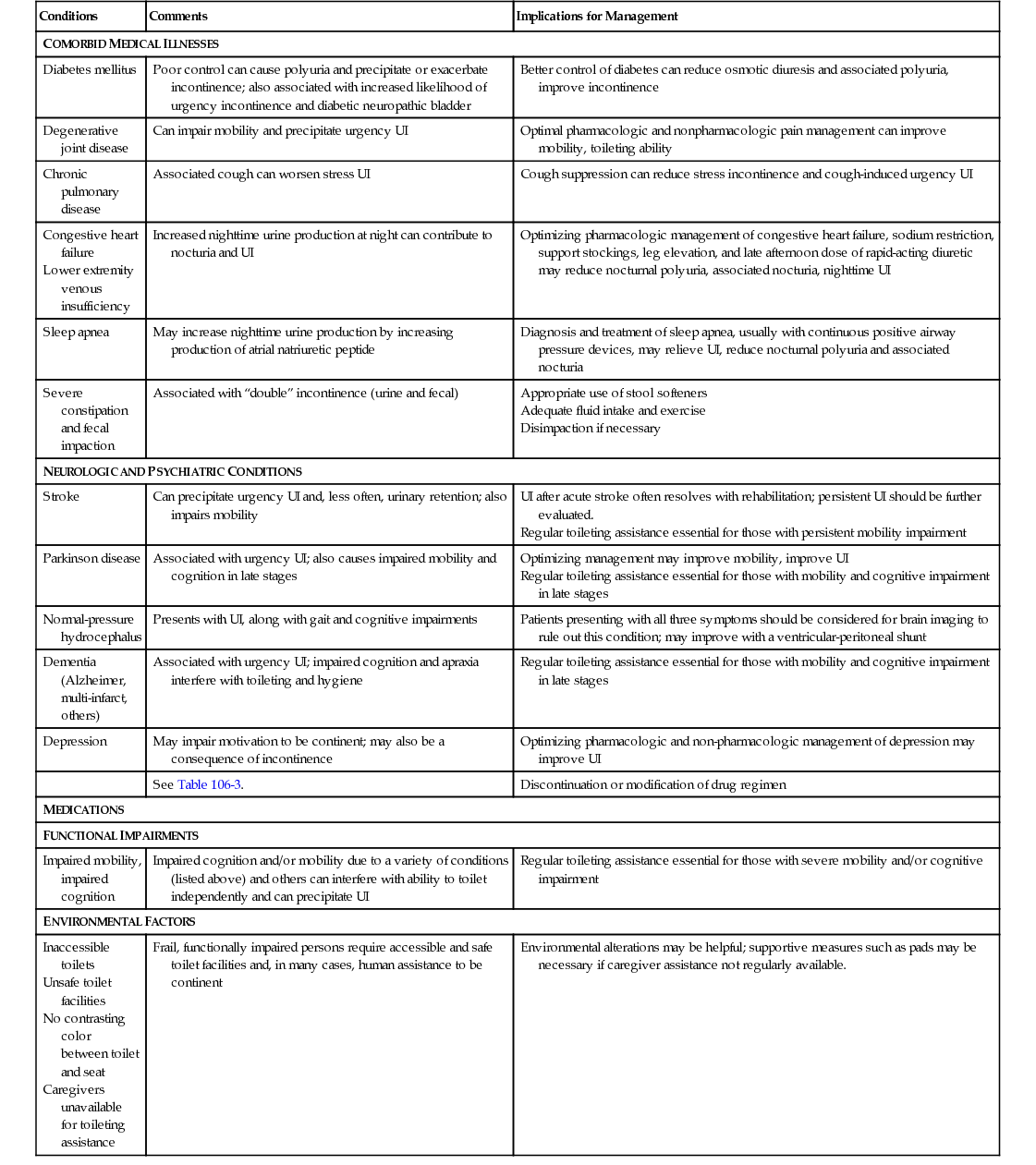

Multimorbidity

Conditions

Comments

Implications for Management

COMORBID MEDICAL ILLNESSES

Diabetes mellitus

Poor control can cause polyuria and precipitate or exacerbate incontinence; also associated with increased likelihood of urgency incontinence and diabetic neuropathic bladder

Better control of diabetes can reduce osmotic diuresis and associated polyuria, improve incontinence

Degenerative joint disease

Can impair mobility and precipitate urgency UI

Optimal pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic pain management can improve mobility, toileting ability

Chronic pulmonary disease

Associated cough can worsen stress UI

Cough suppression can reduce stress incontinence and cough-induced urgency UI

Increased nighttime urine production at night can contribute to nocturia and UI

Optimizing pharmacologic management of congestive heart failure, sodium restriction, support stockings, leg elevation, and late afternoon dose of rapid-acting diuretic may reduce nocturnal polyuria, associated nocturia, nighttime UI

Sleep apnea

May increase nighttime urine production by increasing production of atrial natriuretic peptide

Diagnosis and treatment of sleep apnea, usually with continuous positive airway pressure devices, may relieve UI, reduce nocturnal polyuria and associated nocturia

Severe constipation and fecal impaction

Associated with “double” incontinence (urine and fecal)

NEUROLOGIC AND PSYCHIATRIC CONDITIONS

Stroke

Can precipitate urgency UI and, less often, urinary retention; also impairs mobility

Parkinson disease

Associated with urgency UI; also causes impaired mobility and cognition in late stages

Normal-pressure hydrocephalus

Presents with UI, along with gait and cognitive impairments

Patients presenting with all three symptoms should be considered for brain imaging to rule out this condition; may improve with a ventricular-peritoneal shunt

Dementia (Alzheimer, multi-infarct, others)

Associated with urgency UI; impaired cognition and apraxia interfere with toileting and hygiene

Regular toileting assistance essential for those with mobility and cognitive impairment in late stages

Depression

May impair motivation to be continent; may also be a consequence of incontinence

Optimizing pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic management of depression may improve UI

See Table 106-3.

Discontinuation or modification of drug regimen

MEDICATIONS

FUNCTIONAL IMPAIRMENTS

Impaired mobility, impaired cognition

Impaired cognition and/or mobility due to a variety of conditions (listed above) and others can interfere with ability to toilet independently and can precipitate UI

Regular toileting assistance essential for those with severe mobility and/or cognitive impairment

ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS

Frail, functionally impaired persons require accessible and safe toilet facilities and, in many cases, human assistance to be continent

Environmental alterations may be helpful; supportive measures such as pads may be necessary if caregiver assistance not regularly available.

Dementia

Medications

Medications

Effects on Continence

α-Adrenergic agonists

Increase smooth muscle tone in urethra and prostatic capsule may precipitate obstruction, urinary retention, related symptoms

α-Adrenergic antagonists

Decrease smooth muscle tone in urethra may precipitate stress urinary incontinence in women

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors

Cause cough that can exacerbate UI

Anticholinergics

May cause impaired emptying, urinary retention, and constipation, which can contribute to UI; may cause cognitive impairment, reduce effective toileting ability

Calcium channel blockers

May cause impaired emptying, urinary retention, and constipation, which can contribute to UI; may cause dependent edema, which can contribute to nocturnal polyuria

Cholinesterase inhibitors

Increase bladder contractility, may precipitate urgency UI

Diuretics

Cause diuresis and precipitate UI

Lithium

Polyuria due to diabetes insipidus

Opioid analgesics

May cause urinary retention, constipation, confusion, immobility, all of which can contribute to UI

May cause confusion and impaired mobility and precipitate UI; anticholinergic effects; confusion

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

Increase cholinergic transmission, may lead to urinary UI

Others—gabapentin, glitazones, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs

Can cause edema, which can lead to nocturnal polyuria and cause nocturia and nighttime UI

Evaluation of the Older Adult with Incontinence

Assessing Cognitive Function

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Urinary Incontinence

106