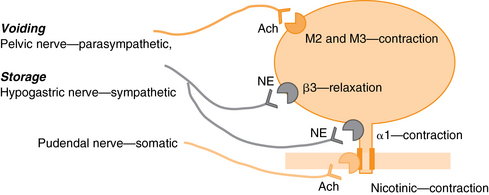

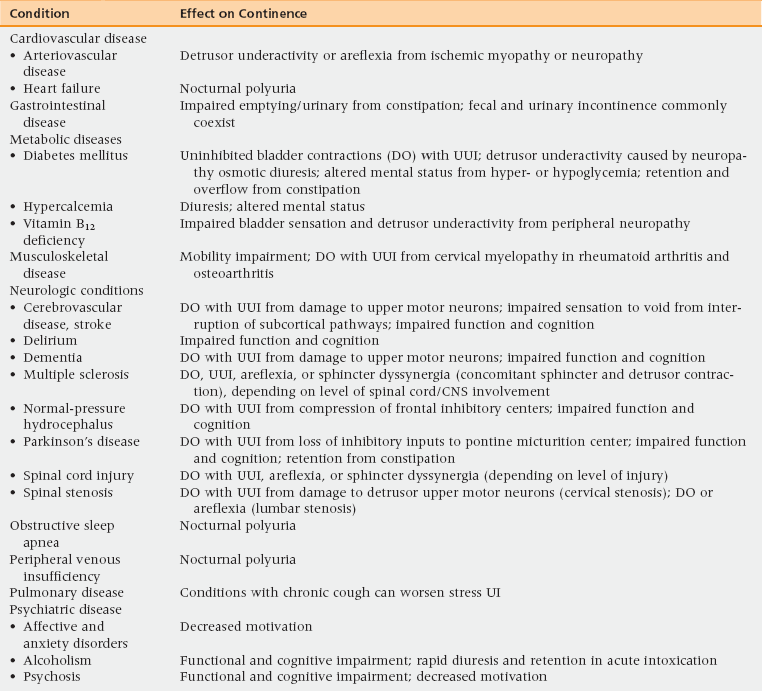

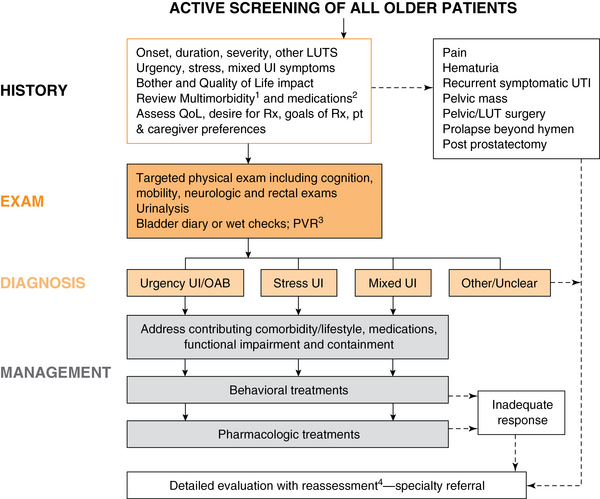

23 Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Discuss the prevalence and impact of urinary incontinence (UI) in older persons. • Describe the impact of medical conditions and medications on continence. • Perform an initial evaluation of incontinence in an older person. • Develop and implement an initial patient-centered treatment plan for incontinence addressing multifactorial causes and tailored to the older person’s goals of care. Urinary incontinence (UI), the complaint of involuntary leakage of urine,1 is one of the major geriatric syndromes. UI may be accompanied by other lower urinary tract symptoms (Table 23-1). TABLE 23-1 Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (LUTS) UI becomes more common with advanced age in both men and women, but is not a normal part of aging. Among women, the prevalence of UI is 15% to 30% in the community,2 50% among the homebound, and 70% in nursing home residents.3 In men, the prevalence is about one third that of women until age 85, when the ratio becomes 1:1. The prevalence of moderate to severe UI (at least weekly or monthly leakage of more than just drops) is 23% among women aged 60 to 79 years and 32% in those 80 and older.3 Among nursing home residents, prevalence rates range from 43% to 77% (median 58%).3 UI severity (i.e., frequency and volume of leakage) also increases with age.4 In a significant number of affected individuals, UI severity will increase if not treated. One third of middle-aged and younger-old women (aged 54 to 79 years) with baseline UI once monthly progressed to leaking at least once a week over 2 years.5 Little is known specifically about the incidence and severity of UI over time in older men. The most common type of UI in older persons is urgency UI6; however, the prevalence of stress UI in men is rising with increased surgical treatment of prostate cancer. The evidence is inconsistent whether race and ethnicity are associated with UI prevalence in older women,7,8 and there are no data on their impact in older men. UI decreases health-related quality of life, with a negative impact on self-esteem, self-perception of aging, activities, and sexuality.9 In older persons, the impact appears greatest in the area of coping with embarrassment with subsequent activity interference, rather than directly precluding activities.10 Among frail nursing home residents, UI adversely impacts social interactions, an important aspect of quality of life in this setting.11 Persons with UI are at risk for urinary tract infections, skin breakdown, falls, and fractures. Associated caregiver burden can lead to depression and is associated with nursing home placement. Approximately 6% to 10% of nursing home admissions in the United States are attributable to UI.12 Economic costs are significant for the individual and the health care system (nearly $20 billion in 2000),13 and have nearly doubled for older persons in the last decade.14 Unfortunately, the majority of the expenses (56%) are consequence costs (e.g., from nursing home admissions and loss of productivity). Treatment and diagnosis account for approximately one third of costs. Out-of-pocket expenses, predominantly for protective undergarments, have been estimated to run from $750 to $900 yearly, or almost 1% of the median annual household income.15,16 Risk factors for UI in older persons reflect the multifactorial nature of the problem. UI shares common risk factors with other geriatric syndromes (e.g., falls and functional dependence), including lower and upper extremity weakness, sensory and affective impairment,17 and radiologic evidence of white matter signal abnormalities suggesting common etiologic pathways.18 Along with age and functional impairment, the main risk factors for UI are female gender, obesity (women) diabetes, stroke, depression, fecal incontinence, and hysterectomy.19–23 Nursing home residents with UI are more likely than continent residents to have impaired mobility, dementia, delirium, and receive psychoactive medications.9 Parity increases the risk of UI in younger women but the impact attenuates with age. Although there is some evidence for a familial predisposition to UI,24 this may not be a significant risk factor in older persons. UI is common in persons with cognitive impairment, which is associated with a 1.5- to 3.5-fold increase in UI risk,25 especially for bothersome UI.26 At the same time, UI is not inevitable even in frail cognitively impaired persons, because the association between cognitive impairment and UI is at least in part mediated by functional impairment and disability.27 The pathophysiology of UI in older persons is multifactorial, resulting from interactions between lower urinary tract abnormalities, neurologic control of voiding, multimorbidity, and functional impairment. The lower urinary tract has two main functions, storage of urine and effective voiding. Key components of the bladder for continence are its detrusor smooth muscle and epithelial layer (the urothelium). Continence is mediated through the actions of the central and autonomic nervous systems (Figure 23-1).28 Storage occurs through sympathetic stimulation of alpha-adrenergic receptors in the smooth muscle sphincter causing contraction, and beta-adrenergic receptors in the detrusor causing relaxation. Voiding occurs with parasympathetic stimulation of muscarinic receptors in the detrusor. The urothelium has rich and varied receptor signaling systems that conduct information about bladder filling and sensation through the sacral spinal cord to pontine and subcortical areas.29 The prefrontal cortex is an important center for suppressing urgency and forestalling voiding.30 The micturition center in the pons coordinates the cortical inhibitory inputs with the afferent signaling from the detrusor to allow storage of a large volume of urine at a low pressure, and adequate bladder emptying through detrusor contraction and sphincter relaxation.28 Maintenance of urethral closure during storage is augmented by support by fascia and the levator ani.31 Very importantly, UI in older persons can be precipitated or worsened by factors outside of the lower urinary tract, including the following19: • Environment (access to toilets) • Medical conditions (Table 23-2) TABLE 23-2 Medical Conditions Associated with Urinary Incontinence Adapted from DuBeau CE. Urinary incontinence. In:Durso SC, Sullivan GM, eds. Geriatrics Review Syllabus: A Core Curriculum in Geriatric Medicine, 8th ed. New York, NY: American Geriatrics Society; 2013, p 246. TABLE 23-3 Medications Associated with Urinary Incontinence Adapted from DuBeau CE. Urinary incontinence. In: Durso SC, Sullivan GM, eds. Geriatrics Review Syllabus: A Core Curriculum in Geriatric Medicine, 8th ed. New York, NY: American Geriatrics Society; 2013. p 245. There are three main types of UI: • Urgency—leakage associated with a compelling, often sudden, need to void • Stress—leakage associated with coughing, laughing, activity UI associated with impaired bladder emptying (“overflow” incontinence) is uncommon even among frail older persons and men with benign prostate disease.19 Overactive bladder (OAB) is a syndrome defined by the symptom of urgency, usually with frequency and nocturia, with or without urgency incontinence.1 Detrusor hyperactivity with impaired contractility (DHIC) is a type of urgency UI seen in frail patients, in which there is a concomitant elevated postvoiding residual volume (PVR).32 Figure 23-2 provides an outline of diagnosis and assessment of UI. Active screening for UI in all older women is strongly recommended, given the high prevalence of UI and known quality gaps in treatment; screening for UI has been incorporated into health care quality process measures such as those from the Assessing Care of the Vulnerable Elderly (ACOVE) project.33 Suggested screening questions are: “Do you ever leak urine/water when you don’t want to? Do you ever leak urine on the way to the bathroom? Do you ever use pads, tissue, or cloth in your underwear to catch urine?”34,35 Screening can be done by clinical staff and patient questionnaires. Figure 23-2 Evaluation and management of patients with UI. Once a patient acknowledges UI, the next step is to characterize and determine the type of UI symptoms (see Table 23-1), including the frequency and volume of leakage. A proxy for the latter can be the frequency of pad changes. Most UI is relatively slow in onset and should not be associated with pelvic pain. Acute onset of UI and the presence of suprapubic, lower abdominal, and/or pelvic pain are red flags for significant underlying neurologic or neoplastic disease, and should prompt quick referral to neurology or urology/gynecology specialists.

Urinary incontinence

Symptom

Description

Urinary incontinence

Involuntary leakage of urine.

Urgency

Compelling, often sudden need to void that is difficult to defer.

Urgency incontinence

Leakage preceded by/associated with urgency. Common precipitants include running water, hand washing, going out in the cold, even the sight of the garage or trying to unlock the door when returning home. The need to “rush to the toilet” and length of time one can forestall an urgency episode are less useful symptoms because they reflect cognition, mobility, toilet availability, and sphincter control as well as bladder function.

Stress incontinence

Leakage with effort, exertion, sneezing, or coughing. Leakage may be provoked by minimal or no activity when there is severe sphincter damage. Leakage coincident with cough, laugh, sneeze, or physical activity suggests failure of sphincter mechanisms. Leakage that occurs seconds after the activity, especially if difficult to stop, suggests a cough-induced uninhibited detrusor contraction.

Mixed incontinence

Presence of both urgency and stress UI symptoms. Patients vary in the predominance, severity, and/or bother of urge versus stress leakage.

Overactive bladder

Symptom syndrome (not a specific pathologic condition) consisting of urgency, frequency, and nocturia, with or without urge incontinence.

Frequency

Complaint of needing to void too often during the day, as defined by the patient.

Nocturia

Complaint of waking at night one or more times to void. If these voids are associated with UI, the term nocturnal enuresis may be used.

Slow (weak) stream

Perception of reduced urine flow, usually compared to previous performance.

Hesitancy

Difficulty in initiating voiding, resulting in a delay in the onset of voiding after the individual feels ready to pass urine.

Straining

Muscular effort either to initiate, maintain, or improve the urinary stream.

Intermittent stream

Sensation that the bladder is not empty after voiding.

Postvoid dribbling

Small amounts/drops of urine after voiding has stopped. More common in men.

Prevalence and impact

Risk factors and pathophysiology

Medication

Effect on Continence

Alcohol

Frequency, urgency, sedation, delirium, immobility

α-Adrenergic agonists

Outlet obstruction (men)

α-Adrenergic blockers

Stress leakage (women)

ACE inhibitors

Associated cough worsens stress and possibly urgency leakage in older adults with impaired sphincter function

Anticholinergics

Impaired emptying, retention, delirium, sedation, constipation, fecal impaction

Antipsychotics

Anticholinergic effects plus rigidity and immobility

Calcium channel blockers

Impaired detrusor contractility and retention; dihydropyridine agents can cause pedal edema, leading to nocturnal polyuria

Cholinesterase inhibitors

Urinary incontinence; potential interactions with antimuscarinics

Estrogen

Worsens stress and mixed leakage in women

Gabapentin, pregabalin

Pedal edema causing nocturia and nighttime incontinence

Loop diuretics

Polyuria, frequency, urgency

Narcotic analgesics

Urinary retention, fecal impaction, sedation, delirium

NSAIDs

Pedal edema causing nocturnal polyuria

Sedative hypnotics

Sedation, delirium, immobility

Thiazolidinediones

Pedal edema causing nocturnal polyuria

Tricyclic antidepressants

Anticholinergic effects, sedation

Differential diagnosis and assessment

1See Table 23-2.

2See Table 23-3.

3Postvoid residual (PVR) test is optional; considered for women with marked pelvic floor prolapse, longstanding diabetes, history of urinary retention or high PVR, recurrent UTIs, medications that impair bladder emptying, chronic constipation, persistent or worsening UI on treatment with bladder antimuscarinics, or prior urodynamic study demonstrating detrusor underactivity and/or bladder outlet obstruction (Grade C). If PVR is elevated (e.g., 200 mL), consider trial of alpha-blocker (men), treat constipation, decrease or eliminate anticholinergic medications and calcium channel blockers, and consider catheter drainage followed by voiding trial if PVR 300 mL.

4Detailed evaluation with reassessment could include the following: bladder diary and PVR, if not previously done; revisiting/testing for comorbidity (e.g., sleep apnea if nocturia with nocturnal polyuria is present); trial of alternative medication for urgency incontinence (another antimuscarinic or switch to beta-3 agonist, if not contraindicated); or addition of biofeedback for pelvic muscle exercise training.

LUT, lower urinary tract; LUTS, lower urinary tract symptoms; OAB, overactive bladder; PVR, postvoiding residual; Rx, treatment; UI, urinary incontinence. (Adapted from DuBeau CE, Kuchel GA, Johnson T, et al. Incontinence in the frail elderly. In: Abrams P, Cardozo L, Khoury S, Wein A, editors. Incontinence. 4th ed. Paris: Health Publications; 2009, p. 961-1025.

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Oncohema Key

Fastest Oncology & Hematology Insight Engine