Update on Classification of Neuroendocrine Carcinomas

Mary Beth Beasley

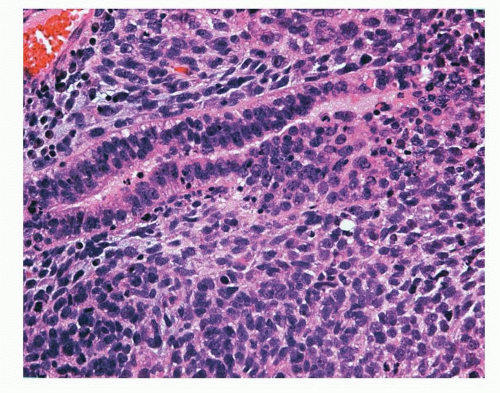

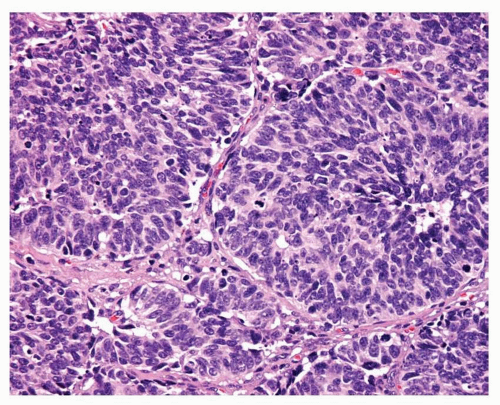

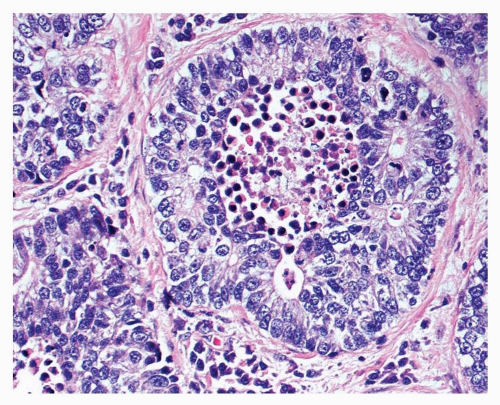

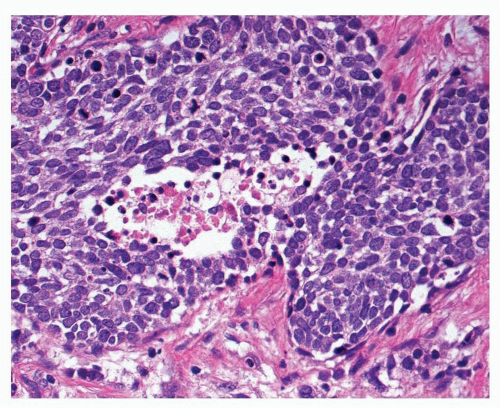

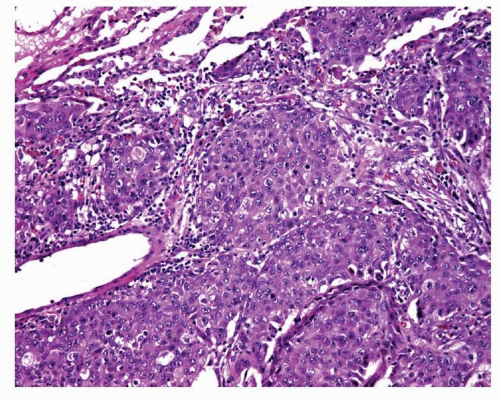

Pulmonary neuroendocrine (NE) carcinomas are generally considered to encompass a spectrum of tumors including the low-grade typical carcinoid (TC) (Fig. 12-1), the intermediate-grade atypical carcinoid (AC) (Fig. 12-2), and the two high-grade carcinomas: large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC) (Fig. 12-3) and small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC) (Fig. 12-4). These tumors have overt neuroendocrine morphology from a histologic standpoint and generally show evidence of neuroendocrine differentiation either immunohistochemically or ultrastructurally (neuroendocrine granules).

The 2004 World Health Organization (WHO) classification of pulmonary tumors does not actually classify the NE carcinomas as a group, although they are typically thought of as representing a continuum.1 Currently, the WHO classification categorizes the two carcinoid subtypes as a group, while LCNEC is a subtype of large cell carcinoma and SCLC is a separate category. LCNEC and SCLC both additionally have a “ combined” subtype as both of these tumors may be combined with other non-small cell lung carcinomas (NSCLCs), such as adenocarcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma, or they may be combined with each other.

Aside from these four tumors, other pulmonary tumors may also exhibit evidence of neuroendocrine differentiation by immunohistochemical methods. Such tumors include pulmonary blastoma, desmoplastic small round cell tumor, paraganglioma, and primitive neuroectodermal tumor (Figs. 12-5 and 12-6).1 Most notably, NSCLC otherwise lacking morphologic features typically associated with neuroendocrine differentiation may exhibit positive staining with neuroendocrine markers such as chromogranin, synaptophysin, or CD56. These tumors are referred to as “NSCLCs with neuroendocrine differentiation.” The reported frequency of this finding is variable but is up to 20% to 30% in some series. The significance of this finding has been the subject of several studies, and while results have been somewhat variable, most series indicate this finding is not of clinical or prognostic significance.2,3,4,5,6,7 and 8 Further complicating the picture is the existence of a group of large cell carcinomas that have overt neuroendocrine morphology from a histologic standpoint yet lack evidence of neuroendocrine differentiation by immunohistochemical or ultrastructural grounds. Such tumors have been termed “large cell carcinomas with neuroendocrine morphology” and the clinical significance of this category is unclear.6,9 The existence of tumors with neuroendocrine morphology yet lacking evidence of neuroendocrine differentiation by immunohistochemical or ultrastructural grounds, and vice versa, has, however, raised the valid point as to whether neuroendocrine tumors should be defined by morphologic or immunohistochemical grounds, or a combination thereof ( Figs. 12-7,12-8 and 12-9).10

The classification of NE carcinomas of the lung has evolved over the years and remains the subject of much debate. Much of the current controversy centers on the continued utilization of the “carcinoid” nomenclature for TC and AC, the criteria for AC, and whether a true distinction exists between LCNEC and SCLC. Other issues have evolved from increasing immunophenotypic, clinical, and molecular information. Reproducibility of diagnoses using the current classification

scheme is also problematic. While agreement is generally good for TC and SCLC, it is less so for AC and LCNEC, even among experienced pulmonary pathologists.11

scheme is also problematic. While agreement is generally good for TC and SCLC, it is less so for AC and LCNEC, even among experienced pulmonary pathologists.11

FIGURE 12-1 High-power image of TC showing characteristic organoid morphology, a uniform cell population, and by definition fewer than 2 mitoses per 10 HPF and lacking necrosis. |

FIGURE 12-2 High-power image of AC showing organoid growth pattern with central punctuate areas of necrosis and mitotic figures. |

FIGURE 12-3 High-power image of LCNEC showing organoid growth and rosette formation. Central necrosis and numerous mitotic figures are present. |

FIGURE 12-4 High-power image of small cell carcinoma is characterized by cells with hyperchromatic nuclei, scant cytoplasm, and numerous mitotic figures. |

FIGURE 12-8 Medium-power image of a large cell carcinoma that shows no rosette formation, necrosis, or peripheral palisading suggestive of LCNEC. |

FIGURE 12-9 Immmunostains performed on the case shown in Figure 12-6 included neuroendocrine markers, and synaptophysin positivity was observed in tumor cells. How to best categorize this tumor remains controversial. |

Criticisms of the current WHO scheme also include the fact that the criteria are applicable primarily to large specimens, whereas the majority of lung carcinomas are diagnosed on small biopsies or cytology specimens, where one may not have sufficient tumor to count mitoses in 10 high power fields (HPF) and evaluation of the growth pattern may be difficult. Currently, it is usually not possible to reliably separate TC from AC on a small biopsy, and it is extremely difficult to make a definitive diagnosis of LCNEC. While sample size and other issues inherent with small biopsies will remain a factor, further evaluation to make the classification more applicable to small biopsies is under investigation.

This chapter addresses some of the more common issues and controversies surrounding this group of tumors at the present time, acknowledging that further study is needed to clarify many of these concerns and, most importantly, to provide clinical relevance to the classification of this group of neoplasms. Detailed pathologic information for each tumor will not be repeated here, and the reader is referred to the respective chapters on each tumor for this information. A summary of the current pulmonary neuroendocrine tumors is presented in Table 12-1, and the current WHO definitions of the major pulmonary neuroendocrine tumors are presented in Table 12-2. The continued debate and need for coordinated study of these tumors have prompted the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer to form an international registry of pulmonary neuroendocrine tumors for detailed study of many of these issues.4

EVOLVING ISSUES WITH CARCINOID TUMOR

The primary issues surrounding carcinoid tumors involve the preferred nomenclature for these tumors and the definition of AC. The concept of a tumor with prognostic and morphologic features “in between” those of TC and SCLC has long been recognized. The first attempt to define AC was made by Arrigoni et al.12 in 1972. Arrigoni proposed that AC be defined as a carcinoid tumor with (a) 1 mitotic figure per 1 to 2 HPF; (b) necrosis; (c) pleomorphism, hyperchromatism, and an abnormal nuclear cytoplasmic ratio; and (d) areas of increased cellularity and disorganization. Arrigoni et al.12 did not specify whether one, multiple, or all of the criteria should be met and many of the criteria are subjective.12 The entity of LCNEC was not proposed until 1991,13

and the current criteria for TC and AC were not proposed until 1998,14 with criteria for both entities incorporated into the 1999 and 2004 WHO classification schemes.1 In the interim, several other authors proposed various classification schemes for ACs using similar criteria to those of Arrigoni et al. and proposals for differing terminology also emerged. Such schemes include those of Paladugu et al.15 who proposed the term “Kulchitsky cell carcinoma” with grade I corresponding to TC and grade II to AC. Mark and Ramirez16 proposed “peripheral small cell carcinoma resembling carcinoid tumor” with subclassification into low and high grades, and Warren et al.17 proposed three subsets of “well-differentiated NE carcinoma” for what would correspond to different grades of carcinoid tumors. These classification schemes clearly include some tumors that would be categorized as LCNEC using the current WHO criteria. While the current definitions of TC and AC appear relatively straightforward on the surface, criticisms remain. Critics are in favor of eliminating the “carcinoid” nomenclature and replacing it with subtypes/grades of “NE carcinoma,” which is felt to better reflect the biologic potential of the tumors, while proponents of the “carcinoid” scheme argue that retention of the traditional nomenclature reduces potential confusion associated with a nomenclature shift. Critics of the current WHO scheme further argue that the current definition of AC places too much emphasis on a single criterion, namely mitotic activity. Indeed, one major pulmonary pathology textbook currently recommends the use of the criteria of El-Naggar et al.18,19 In this scheme, neuroendocrine tumors are classified as “grade 1”, “grade 2,” and “grade 3” NE carcinomas. In this classification, grade 2 is essentially equivalent to AC, and criteria are a mitotic rate of 5 or more per 10 HPF, discernable nuclear pleomorphism, at least focal necrosis, and at least focal loss of organoid growth pattern. It is recommended that at least two of these criteria should be present to make this diagnosis.19 Continued study of these tumors in a systematic fashion will hopefully provide clarification of this area, but it should be noted that consistent use of existing criteria should be employed to facilitate uniform study of this group of tumors.

and the current criteria for TC and AC were not proposed until 1998,14 with criteria for both entities incorporated into the 1999 and 2004 WHO classification schemes.1 In the interim, several other authors proposed various classification schemes for ACs using similar criteria to those of Arrigoni et al. and proposals for differing terminology also emerged. Such schemes include those of Paladugu et al.15 who proposed the term “Kulchitsky cell carcinoma” with grade I corresponding to TC and grade II to AC. Mark and Ramirez16 proposed “peripheral small cell carcinoma resembling carcinoid tumor” with subclassification into low and high grades, and Warren et al.17 proposed three subsets of “well-differentiated NE carcinoma” for what would correspond to different grades of carcinoid tumors. These classification schemes clearly include some tumors that would be categorized as LCNEC using the current WHO criteria. While the current definitions of TC and AC appear relatively straightforward on the surface, criticisms remain. Critics are in favor of eliminating the “carcinoid” nomenclature and replacing it with subtypes/grades of “NE carcinoma,” which is felt to better reflect the biologic potential of the tumors, while proponents of the “carcinoid” scheme argue that retention of the traditional nomenclature reduces potential confusion associated with a nomenclature shift. Critics of the current WHO scheme further argue that the current definition of AC places too much emphasis on a single criterion, namely mitotic activity. Indeed, one major pulmonary pathology textbook currently recommends the use of the criteria of El-Naggar et al.18,19 In this scheme, neuroendocrine tumors are classified as “grade 1”, “grade 2,” and “grade 3” NE carcinomas. In this classification, grade 2 is essentially equivalent to AC, and criteria are a mitotic rate of 5 or more per 10 HPF, discernable nuclear pleomorphism, at least focal necrosis, and at least focal loss of organoid growth pattern. It is recommended that at least two of these criteria should be present to make this diagnosis.19 Continued study of these tumors in a systematic fashion will hopefully provide clarification of this area, but it should be noted that consistent use of existing criteria should be employed to facilitate uniform study of this group of tumors.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree