As our understanding of the biology of breast cancer evolves, we recognize that there are many different types of histologically distinct cancers. Breast cancer is ahead of many other solid organ malignancies in our understanding about different tumor biologies. We routinely differentiate breast cancers based on histology between invasive ductal carcinoma and invasive lobular carcinoma. We also divide breast cancers into approximated subtypes based on their hormone receptor status (estrogen and progesterone) as well as HER-2/neu status.

There are some other breast histologies that are not as common as invasive ductal and invasive lobular carcinomas. All practitioners caring for patients with breast complaints should be aware of these unusual histologies and know how to identify them as well as where to look for guidance in treating them. Recognition of these unusual histologies will allow surgeons to recommend appropriate treatment. It will also aid in counseling patients regarding the prognosis based on the best information available.

This chapter includes unusual histologies which may be more challenging to recognize and manage partly because of their infrequent occurrence. The surgeon seeing patients with breast complaints should be familiar with these lesions in order to ensure the appropriate diagnostic evaluation and management. Accurate diagnosis is highly dependent on the availability of other specialists in the multidisciplinary team (pathologists, radiologists, medical oncologists) who can aid in the evaluation and treatment of patients with these unusual tumor types. Table 74-1 provides a summary of key facts and management of the histologies covered in this chapter.

Unusual Breast Histologies

| Unusual Histology | Presentation | Diagnosis | Pathology/Molecular Biology | Surgical Management | Adjuvant Therapies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atypical vascular lesion | Postradiation therapy skin changes: papules, erythematous patches or bruising | Punch or excisional biopsy |

| Biopsy and consider excision if suspicious or changing | None |

| Angiosarcoma |

|

| Spongy, hemorrhagic tumor with freely anastomosing vascular channels with atypical endothelium Secondary more likely to be high grade |

| Chemotherapy dependent on stage, new regimens being tested |

| Medullary carcinoma |

|

| >75% syncytial growth pattern Often expresses HLA-DR and TP53 mutation; usually negative for ER, PR, HER-2/neu. |

| Radiation and chemotherapy as indicated by stage and NCCN guidelines |

| Metaplastic breast cancer | Presents as a palpable mass or indeterminate imaging finding; distant metastases 4.6–10% |

| Mix of adenocarcinoma with dominant areas of differentiation: spindle cell, squamous, or mesenchymal; usually negative for ER, PR, HER-2/neu |

| Adjuvant radiation as indicated by NCCN guidelines Chemotherapy as indicated by stage, but may have poor response |

| Squamous subtype metaplastic breast cancer |

|

|

|

| Adjuvant radiation and chemotherapy as indicated by stage following chemotherapy for other squamous cell carcinomas |

| Mucinous carcinoma |

|

| Pure mucinous carcinoma all tumor tissue produces extracellular mucin Usually well-differentiated |

| Consider adjuvant radiation therapy if breast-conserving surgery is performed |

| Papillary carcinoma |

|

|

|

| Intracystic no additional therapy. Solid consider adjuvant radiation after breast-conserving surgery Adjuvant endocrine therapy as clinically indicated |

| Secretory carcinoma |

|

| Cells contain multiple secretory vacuoles; usually ER, PR, and HER-2/neu negative |

| Unclear role of adjuvant radiation and chemotherapy Avoid radiation in young patients |

| Tubular carcinoma |

|

|

| Breast-conserving surgery or mastectomy Consider SLNB for tumors over 1–1.8 cm | Adjuvant radiation therapy with breast-conserving surgery Hormonal or chemotherapy as indicated by stage |

| Adenoid cystic carcinoma |

|

|

|

| Adjuvant radiation after breast-conserving surgery Hormonal therapy if ER/PR positive |

| Lymphoma |

|

|

| Surgery is not the primary treatment for lymphoma | Chemotherapy is the treatment once lymphoma is diagnosed |

| Neuroendocrine carcinoma |

|

|

|

| Adjuvant radiation after breast-conserving surgery Monotherapy with chemotherapy or endocrine therapy as indicated by stage |

Atypical vascular lesions of the breast are associated with radiation therapy after breast-conserving therapy. They can occur within 1 year after treatment or several years later.

Lymphatic-type atypical vascular lesions stain positive for CD31, D2-40, and possibly for CD34. Vascular-type atypical vascular lesions stain positive for CD31 and CD34 and negative for D2-40.1 While these lesions can often be differentiated from angiosarcomas based on histopathologic features, additional testing may be helpful. Recently, secondary angiosarcomas have been shown to have high levels of FISH amplification of MYC whereas atypical vascular lesions show no MYC amplification.2

Histopathologic characteristics of atypical vascular lesions have been divided into lymphatic type and vascular type. The lymphatic-type lesions are usually confined to the upper dermis and composed of thin-walled clusters of ectatic vessels with thin walls. They can contain more irregular lymphatic vessels and have a more infiltrative growth pattern similar to a well-differentiated angiosarcoma. The vascular-type lesions can involve the superficial and deep dermis. The vessels within them are irregular and may be dilated. The endothelium is single-layered but may have some atypia. Unlike angiosarcomas, the vessels within these lesions do not intercommunicate with each other.1

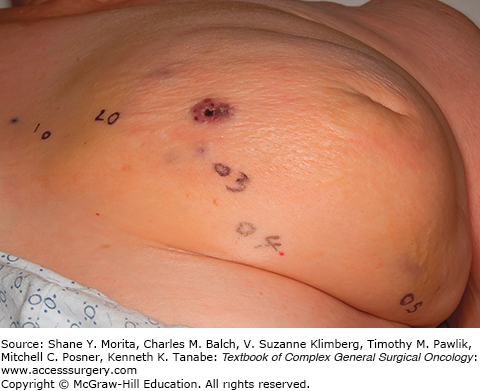

The clinical appearance of vascular lesions may be subtle as demonstrated in Fig. 74-1. They can appear as fleshy papules, erythematous plaques or patches, or bruise-like skin changes. It is not uncommon to have telangiectasias of irradiated skin, particularly after postmastectomy radiation. These changes should be monitored closely. New vascular lesions arising after radiation therapy are suspicious and should be evaluated carefully.1

No specific staging is necessary if only benign changes are shown. Each lesion should be considered separately and evaluated as clinically indicated.

The prognosis for atypical vascular lesions is dependent on whether they progress to angiosarcomas. Patients with atypical vascular lesions will have recurrent lesions 10% to 20% of the time. It is unclear how often these lesions progress to angiosarcoma but it appears to be rare.1

Punch biopsy of skin lesions should be performed to histologically evaluate vascular skin changes in the previously irradiated breast. A high index of suspicion is necessary as these could represent an angiosarcoma.

Biopsy of any suspicious vascular skin lesions is recommended to allow histological assessment and to determine whether they are atypical vascular lesions or angiosarcomas. Skin recurrence of the primary breast cancer may also appear with subtle skin changes, so a high index of suspicion is important to allow early diagnosis. Close clinical follow-up is recommended even if biopsy shows a benign lesion to ensure no progression of changes to suggest a malignancy. If there is a question about the diagnosis or if additional skin changes develop, additional tissue should be obtained for evaluation.

Angiosarcoma of the breast can develop as a primary tumor or as a secondary tumor occurring after treatment of breast cancer with breast-conserving surgery and radiation therapy. Primary angiosarcoma of the breast occurs most commonly in females aged 30 to 50 years. Secondary angiosarcoma most commonly occurs 5 to 10 years after radiation therapy but can occur outside of that time period as well. The age of patients with secondary angiosarcoma is typically older than primary angiosarcoma—median age in a series of patients treated from 1966 to 2008 at Mayo Clinic was 73 years. Secondary angiosarcoma of the breast has an incidence of 7 in 100,000 person years.3

Information on the molecular biology of angiosarcomas in general shows overexpression of angiogenic cytokines including VEGF-A. They have been shown to overexpress VEGF receptor subtype 2 but not subtypes 1 and 3. It is common to find mutations in TP53 in angiosarcomas.4

Grossly, the tumor appears spongy and hemorrhagic. On microscopic examination, the diagnostic feature is that the tumor contains areas of freely anastomosing vascular channels with atypical endothelium. It may also contain areas of undifferentiated solid tumor or bland cytologic areas.5 Secondary angiosarcoma is more likely to be high grade than primary angiosarcoma. Neither tumor size nor grade is associated with survival.3

The presentation of these two tumors has been shown to be different in at least one study with primary angiosarcoma most commonly presenting as a palpable mass. Secondary angiosarcomas usually present with skin changes and patients complaining of a rash (Figs. 74-2 and 74-3). Most of those patients will have a mass on imaging, although not always. Median tumor size at presentation is around 5.8 cm. Lymph node involvement is uncommon in angiosarcoma of the breast.

Staging evaluation should follow the NCCN guidelines for soft tissue sarcoma staging.6

The prognosis is poor for both primary and secondary angiosarcoma of the breast compared to other breast cancers. Local recurrence is common even with adequate resection margins.7 Median survival has been reported to range from 1 to 3 years for secondary angiosarcoma.7 Overall 5-year survival has been reported as 46% for primary angiosarcoma and 69% for secondary angiosarcoma. Ten-year survival is less than 30% for both. The most common site of metastasis is bone followed by lung then liver.3 For secondary angiosarcoma, older age and depth of tumor invasion has been shown to correlate with worse prognosis.7

Physical examination is often the key to diagnosing angiosarcoma. In particular, the surgeon should have a high index of suspicion when atypical vascular lesions are noted on the breast whether or not the patient has had prior radiation treatment. Mammogram may show a mass or skin thickening, but it may also be nondiagnostic. Ultrasound may show a mass or skin thickening, but again can be nondiagnostic. MRI may show a mass. The key to diagnosis is biopsy of suspicious skin lesions and consideration of incisional biopsy if punch biopsies or core needle biopsies are nondiagnostic with a clinical suspicion of possible angiosarcoma.

The primary treatment for any angiosarcoma is complete resection known as R0 resection. Surgical management of breast angiosarcoma involves excision with wide margins. There is not a role for breast-conserving surgery. Due to the high rate of local recurrence, many surgeons try to achieve wide margins of 3 cm or more. Unfortunately, it may be difficult to resect to uninvolved margins at the time of surgery.4,8 Total mastectomy may not be enough to achieve adequate margins and skin graft or autologous tissue transfer may be required to close the surgical wound. Since complete excision is associated with improved survival when compared to incomplete excision, attempts should be made to completely excise the tumor even if it requires reconstruction to close the defect.8

There is not a clear role for adjuvant radiation therapy. Traditional chemotherapy for breast angiosarcoma is similar to that for soft tissue sarcomas which is doxorubicin based. More recently, docetaxel, paclitaxel, and inhibitors with anti-VEGF activity including sorafenib, bevacizumab, and brivanib have showed promise when used in secondary angiosarcoma.3,7 Further study is necessary and should include further exploration of molecular testing of tumors for targeted therapy.

Medullary carcinoma accounts for <5% of breast cancers. The median age is 50 years.9 One important epidemiologic observation is that a higher percentage of the breast cancers that develop in patients with deleterious mutations in the BRCA1 gene have medullary features.5

Medullary carcinoma has many similar features to invasive ductal carcinoma on immunohistochemical staining. This includes usually staining positive for CK-7, vimentin, S-100 protein, and p53, and staining negative for CK20. It also frequently expresses HLA-DR which has been proposed to explain the lymphocytic infiltrate. On genetic testing, medullary carcinoma usually has the TP53 mutation. They are usually negative for estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and HER-2/neu overexpression.5 Hence, medullary carcinoma is often described as being similar to basal-like breast cancers. However, some studies have reported rates of ER positivity as high as 30% to 40%. This raises questions about the exact definition of medullary carcinoma in these studies.

On histology, medullary carcinomas of the breast have a predominantly syncytial growth pattern, >75%. Typically, it has a diffuse lymphocytic infiltrate concentrated at its periphery.5 There are two histologic types reported, typical and atypical. Ridolfi et al reported the typical type as having well-circumscribed margins, no intraductal component, no microglandular features, and a moderate to marked diffuse mononuclear stromal infiltrate. It was usually grade 1 or 2. They described the atypical type as having focal or prominent margin infiltration, a component of intraductal carcinoma, microglandular features, and mild to negligible mononuclear infiltrate. It was usually grade 3.10

There is concern that the atypical type is not precisely defined and may be confused with solid undifferentiated breast carcinomas that are not truly medullary carcinomas. This could lead to an incorrect understanding of the tumor and its prognosis.5

Medullary carcinoma of the breast has a median tumor size around 2.2 cm. It frequently presents with axillary lymph node involvement but not distant metastasis.9

Staging evaluation should follow the NCCN guidelines for invasive breast cancer.11 Axillary staging is important.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree