Readmissions following major oncologic operation are common—affecting patient treatment, outcome, and hospital resources. The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services mandates reporting of certain disease-specific readmissions and Congress is considering using individual hospital readmission rates as a performance measure. Studies using administrative data demonstrate that readmission rates following major cancer surgery are high. Administrative data cannot determine causes. Single-institution studies demonstrate length of hospital stay and comorbidities as risk factors. Discharge processes and outpatient healthcare utilization can be improved. Until studies on readmission rate are conducted, using readmission rates as a measure of quality should be pursued cautiously.

- •

Readmission rates following major cancer surgery are between 16% to 25% at 30 days and 53% to 66% at 1 year.

- •

Review of the literature revealed several risk factors predictive of readmissions, such as age, comorbidities, and hospital length of stay.

- •

Future readmission studies are needed to evaluate the global processes of surgical care and their impact on readmission rates. The authors provide a conceptual framework for conduction of these studies in a prospective manner.

- •

The proposed congressional plan to use readmission rates to assess hospital performance and determine reimbursement should be pursued with extreme caution, pending further investigation.

Given the aforementioned interest in readmissions as an indicator of quality and the potential to adjust payment for readmissions, surgeons should take action to further develop and perfect the study of postoperative readmissions and evaluate the validity of using readmissions as a measure of quality. The first area of investigation should be to determine a universally accepted postoperative length of time for which an unexpected readmission is linked or related to the “quality” of the care delivered during the surgical admission. Most surgeons continue to fall back on 30-day morbidity and mortality as the time frame to be judged because it is generally assumed that the more time elapsed between discharge and readmission the less likely it is that the prior hospitalization played a significant role. This is significantly shorter than the 90-day global period that Medicare has developed. The payment for a surgical procedure includes a standard package of preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative services. The preoperative period included in the global fee for major surgery is 1 day and the postoperative period for major surgery is 90 days. Thus, it seems that Medicare has defined 90 days as an appropriate length of time to hold the surgical care team accountable. However, this time frame for major oncologic operations should be scrutinized for validity before it is accepted. Considering that oncology patients are generally older with more comorbidities, unexpected and unpreventable postoperative hospital admissions may be higher at baseline compared with an operation for a benign condition.

Research into unexpected hospital readmissions has sought to define characteristics of and risk factors for those readmissions. They can essentially be broken down into four groups: preoperative risk factors (age, comorbidities, disease extent, cancer stage), initial hospitalization risk factors (length of operation, length of stay, perioperative complications), discharge disposition status (home alone, home with family, home with home health, rehabilitation facility, nursing home), and, finally, the reasons for readmission (operative complication, pneumonia, dehydration, bleeding). However, many of the currently available papers are lacking the ability to demonstrate a causal association between substandard inpatient care and early readmission, which would be the cornerstone of using readmission as a quality-care indicator.

Outcomes and readmission data for most complex oncologic operations are generated from retrospective case series reviews of large, single institutions with a high volume of the specific operation being studied. As these institutions continue to develop broader geographic catchment areas, the ability for them to accurately record the absolute number of patient readmissions is decreasing. Patients are often willing to travel great distances, and across state lines, to have an operation at a high-volume center; however, often present to the closest available emergency room when postdischarge problems arise. Therefore, the data from single-institution series often underestimate the actual readmission rate. Moreover, regionalization of major abdominal operations has been promoted given the positive volume–outcome relationship demonstrated in many complex oncologic procedures. High-volume centers have demonstrated decreased operative time and hospital length of stay as evidence of improved quality of care. Interestingly, as hospital length of stay has decreased it was speculated that the number of hospital readmissions due to conditions and complications that would have manifested during a longer initial hospitalization would be on the rise. This is not borne out by the data; in fact, an increase in initial hospital length of stay is commonly reported as an independent risk factor for future readmissions.

Given the inaccuracy of hospital readmission rates from single-institution reports, recent effort has been put forth to extract population-level data from administrative data sets, including the Medicare fee-for-service database linked to state or national cancer registries (eg, the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results [SEER] registry). This type of linked data set provides accurate readmission data regarding dates, duration, and hospital of readmission. Linking this data with cancer registry data allows tumor-specific data (eg, American Joint Committee on Cancer stage and pathology) to be added and allows for proper stratification and comparison of outcomes.

One of the initial papers utilizing one of these large administrative data sets linked to a statewide cancer registry database was by Yermilov and colleagues. They performed a population-based study for all patients in California undergoing a pancreaticoduodenectomy for adenocarcinoma between 1994 and 2003, which resulted in a patient cohort of 2023 patients. They demonstrated a 59% readmission rate in the first year, with 47% of those patients being readmitted to a hospital other then the one at which they had their operation. Advanced age, higher Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), higher T-stage, and longer initial hospitalization were all positive predictors of readmission. They also sought to bring attention to the causes of readmission, such as dehydration and electrolyte abnormalities, which they propose may have been prevented with the implementation of additional processes, such as patient education, home health services, and improved communication with primary care providers.

Administrative databases also attempt to collect data on comorbidities that are important to help risk adjust readmission data. The CCI, referred to in many of the following studies of surgical readmissions, is a weighted scale developed by epidemiologist Mary Charlson in 1987. It assigns a value to a patient’s overall comorbidities in an attempt to assess risk for 1-year mortality. It involves heart disease, vascular disease, pulmonary disease, diabetes, renal disease, liver disease, malignancy, and AIDS as potentially weighted conditions. Charlson and colleagues also combined an age-adjusted CCI with their standard comorbidity index to assess the additional mortality risk of patients greater than 40 years old. Articles researching outcomes in patients who have cancer occasionally use a modified CCI that removes malignancy as a weighted condition because this is assumed to be present in all the patients. The CCI is an important tool in the preoperative risk assessment of a patient to determine what unmodifiable patient-level factors may contribute to risk for surgical complication and readmission.

In addition to the Yermilov and colleagues study, the University of California Los Angeles, under the direction of Clifford Ko, has compiled data (Clifford Ko, unpublished, 2011) on early readmission rates (defined as within 30 days following surgical treatment of lung and gastrointestinal [GI] cancers) between 1994 and 2004. Preliminary results demonstrate that for patients undergoing surgical resection for stomach cancer (subsample size 12,769), the 30-day readmission rate is 25.6%, and the 1-year readmission rate approaches 66%. Similar to the Yermilov findings, positive predictors for readmission included increasing the CCI score, any hospitalization in the year before the operation, distant disease at the time of the operation, and increased length of stay following their surgery. Patients that were discharged to home were less likely to need a readmission within 30 days then those discharged elsewhere. The most common reason sited for readmission was a surgical complication accounting for 41% of readmissions. Surgical complications were followed by hypovolemia, pulmonary dysfunction, and nutrition, collectively accounting for another 47% of readmissions.

In 2010, Greenblatt and colleagues published a population-based study using the SEER linked-Medicare database for all patients undergoing colectomy for colon cancer from 1992 to 2002. This study included 42,348 patients discharged after colectomy and demonstrated an 11% readmission rate within 30 days, with 13.2% of patients being readmitted to a hospital other than the one they initially had their surgery. The following factors were found to be predicative of readmission: male gender; hospitalization for any reason in the year before operation, comorbidities, nonelective surgery, prolonged hospital stay (>15 days), blood transfusion, ostomy creation, and discharge to a nursing home. Additionally they found a 1-year, stage-adjusted, survival advantage associated with patients who did not require a readmission, the magnitude of which was comparable to the difference in mortality between patients with stage I disease and those with stage III.

Reddy and colleagues also used the SEER-Medicare–linked data from 1992 to 2003 for all patients undergoing pancreatic resection for adenocarcinoma (76% Whipple, 18% distal, 3% total, and 3% not otherwise specified). They found 1730 patients that met their criteria and demonstrated a 16% readmission rate at 30 days and 53% at 1 year. The reason for readmission was related to operative complications in 80% of patients readmitted within 30 days. Their definition of operative complication was quite broad and included abscesses, sepsis, hemorrhage, pancreatic fistula, GI bleed, urinary tract infection, pneumonia, respiratory failure, and venous thromboembolism or pulmonary embolism. Their analysis produced type of operation (distal pancreatectomy) and length of stay (>10 days) as predictive of early readmission, while age, race, sex, CCI, tumor stage, and node status were not found to statistically impact readmission rates. Interestingly, this study demonstrated that distal pancreatectomy had a higher rate of readmission than a pancreatic head resection. The investigators propose this may be partially due to higher rates of pancreatic leak and that distal pancreatectomies are less likely to be performed at high-volume centers.

These large population-based studies provide excellent baseline statistics for readmissions. They are able to effectively produce an accurate overall rate of readmission because they are capable of capturing all readmissions, even those to hospitals other than where the original operation was performed. The consensus between these studies is a readmission rate of 16% to 25% for major oncologic operations at 30 days and 53% to 66% at 1 year. They are also capable of providing global factors associated with readmission, such as increased length of hospitalization, any hospitalization in the year prior, and increased comorbidity index.

Medicare data and Medicare-linked databases are good sources of information on inpatient, outpatient, hospice, and home health claims for the elderly. However, the information may not be able to be generalized to the population at large because it is obtained only from those patients over 65 years of age. Medicare data are also limited in regard to lack of information on services not covered under the program and services reimbursed by third-party payers. Regarding cancer outcomes research, administrative data sets are often lacking because they do not contain information on the cancer stage or metastasis because these do not affect reimbursement. To overcome this limitation, as mentioned previously, administrative data sets are merged with a tumor registry such as SEER, National Cancer Data Base, or a statewide cancer registry. SEER data provide information on patient demographics as well as tumor grade, primary site, and extent of disease. Limitations within the SEER database include that the information obtained is not standardized and, whereas some tumors may be reported according to the TNM-staging criteria, others are reported more vaguely with descriptors such as “localized” or “distant.” The very large sample size associated with administrative data sets also allows the potential to determine statistically significant differences ( P <.05) even when the absolute difference is very small and possibly clinically insignificant.

Another important limitation of administrative data sets includes a certain inherent level of bias because procedures that are reimbursed, such as operations or length of hospital stay, are likely to be more accurately recorded than subjective patient-level characteristics, such as the comorbidity status of a patient or complications. Although comorbidities tend to be undercoded, CCI data derived from administrative data perform well when compared with the index derived from medical record chart review. Using claims data for risk assessment is also limited because there is no way to assess whether a specific diagnosis was present on admission or occurred during the hospitalization. In addition, each admission has a “principle diagnosis” code from International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification . However, it also has up to 25 other diagnoses coded for that admission. One can imagine the confounding situation when the principle diagnosis for a readmission is recorded as “pancreas cancer” but the secondary diagnosis and true reason for early postoperative readmission is dehydration or biliary obstruction. This is a major limitation of analyses of administrative datasets in trying to assign true cause for readmission.

Although single-institution studies may not be able to produce the same accuracy of data regarding overall readmission rates, they are able, through chart review, to provide much more accurate accounts of reasons for readmissions and patient comorbidities at the time of admission. Furthermore, they are better prepared to assess hospital policies and health care processes, such as multidisciplinary discharge rounds, and the impact on rates and causes of readmission. The following three studies are single-institution studies designed to study their own rates of postoperative readmissions.

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center performed a review of all pancreatic resections performed at their facility between 2001 and 2009, resulting in 578 patients (371 Whipple, 187 distal, 11 total, and 9 other). They recorded a readmission rate of 19% in the first 30 days with only 2% of patients requiring readmission between 30 and 90 days. The only factors found related to risk of readmission were a small pancreatic duct, postoperative complications, and increased length of stay. Additionally, they demonstrated that patients discharged to home with home nursing required more readmissions then those sent home without nursing or those sent to a rehabilitation facility. The group also was able to evaluate the increase in cost associated with early readmission after pancreatic resection. They demonstrated a greater than 10,000 dollar cost associated with the readmission and, for those requiring readmission, their original hospitalization was, on average, 6000 dollars more expensive.

Morris and colleagues performed a retrospective case series analysis at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania of the administrative data for all discharges from their mixed surgical unit in 2009. They were able to show a 3% unexpected readmission rate within 30 days. They found that longer hospital length of stay as well as deep venous thrombosis or acute renal failures during the original hospitalization were associated with increased risk of readmission. The 30-day readmission rates were significantly below the national average of 10% to 20% and they proposed that this could be, in part, due to the lower average age of their patients or the use of daily multidisciplinary rounds, with social workers and discharge planners who carefully evaluate patient’s needs and timely coordination of transitions in care.

In 2010, Stimson and colleagues published a single-institution retrospective case series review of all radical cystectomies performed between 2001 and 2007 at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. They found a 26% readmission rate in the first 90 days and, of those, 19.7% were readmitted in the first 30 days. They showed gender, CCI, tumor stage, and any postoperative complication as independent predictors of 90-day readmission. The CCI was a significant risk factor because it demonstrated an odds ratio for readmission of 1.19 per unit increase in the composite score. For example, a patient with diabetes, previous myocardial infarct, and chronic pulmonary disease has a CCI score of 3 resulting in a 40% increased risk of being readmitted compared with a patient whose only comorbidity is diabetes (CCI score 1).

These single-institution studies were able to accurately record patient-level comorbidities and assess the impact of those comorbidities on rates of readmission. Additionally, they can more accurately assign the true “reason” or diagnosis associated with the readmission. This allows the hospital to assess their own policies and health care processes and make a rational determination of whether they have an impact on readmissions. Finally, single-institution studies allow for proposal and implementation of novel processes, derived from local-studies data, which may limit the number of future readmissions.

Summary

Unexpected readmissions are a significant drain to hospital resources and are a contributing factor for the rising cost of health care in the United States. Outcomes, surgical complications, and readmission data for most complex oncologic operations are generated from retrospective case series of large single institutions with a high volume of the specific operation being studied. As patients travel greater distances to tertiary care centers for their complex operations, the ability of these retrospective studies to capture all of the readmissions decreases. In two large population-based studies, this is demonstrated by the difference in readmission rates to hospitals other than the one where the original operation was performed. Greenblatt and colleagues studied colectomy for colon cancer, which is commonly performed by general surgeons or colorectal surgeons in community hospitals. Yermilov and colleagues studied pancreaticoduodenectomy, a complex operation that is being progressively performed only at high-volume centers. The difference in the readmission rates of patients to hospitals other than the one performing the operation was significant, with only 13% after colectomy and 47% after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Furthermore, studies that fail to account for the proportion of patients readmitted to a different hospital are ignoring the subset of patients that elect to be readmitted to a different hospital because of some perceived substandard care at the first hospital.

A readmission, although costly to the hospital and insurance payers, has an even more significant negative effect on the patient. It has been repeatedly demonstrated that patients requiring readmission after surgery have worse median survival than those not requiring readmission. Many of these readmissions are potentially preventable. It has been demonstrated that patients surviving the initial insult of an early readmission have long-term survival similar to those not requiring an early readmission. Thus, suggesting that the impact on median survival of these readmissions may be due to preventable or reversible acute problems arising early in the postoperative course.

Dehydration, venous thromboembolism, pulmonary embolism, pneumonia, gastritis, and GI bleed are commonly reported causes for hospital readmissions in the first 30 days postoperatively. These causes represent a significant area for improvement because most, if not all, of these are potentially preventable causes of readmissions. For example, rates of readmission secondary to gastritis or GI bleed could be reduced with an intervention as simple and inexpensive as ensuring that all postoperative patients are discharged on acid suppressive therapy unless contraindicated. Further investigation is needed to review the specific causes for early readmission and develop steps that can be taken in the initial hospitalization and in the early postdischarge time frame to decrease preventable causes. Notably, most of the risk factors predictive of future readmissions are not modifiable, such as age, comorbidities, or a complication. However, they may serve as identifiers for patient preoperative and postoperative risk assessment. This assessment would reduce readmissions by allowing a more appropriate and candid patient-surgeon discussion about the risks, temper expectations, and perhaps dictate a higher level of vigilance in the postoperative period.

Extending the current readmission rate analysis beyond the 30-day window would provide a more accurate understanding of the cost, both in morbidity to patients and in costs to the institutions and insurers associated with major oncologic operations. This would also more properly align the research of readmissions with what Medicare has already deemed to be the appropriate window of 90-days. The obvious problem with a 90-day window when dealing with some aggressive cancers is progression of disease and the impact of adjuvant therapy. Most studies have supported the continuation of the 30-day window because most readmissions occur in the first 5 to 10 days and trend downward after that. Greenblatt and colleagues 7 and Yermilov and colleagues show histograms showing the number of readmissions per postdischarge day. The graphs demonstrate that most readmissions occur in the first 2 weeks and then trail off significantly. However, these studies do not demonstrate a trend to zero and a significant number of patients continue to be readmitted in this later time frame.

Patients sometimes have unrealistic expectations of how quickly they will return to full functional status and, in very anxious patients, may cause them to request readmission prematurely. This circumstance may be preventable with improved preoperative and discharge patient education and assessment of home-environment needs. Postdischarge care is equally important. Patients with timely and appropriate postdischarge visits with their primary care provider may be less likely to require readmission. A dedicated study in this area, however, is not available. Readmissions may be a better indicator of the spectrum of both inpatient and postdischarge care rather than simply inpatient care. Further investigation is necessary to understand the relative contributions of failures in discharge planning, insufficient outpatient resources, underuse of supportive palliative care programs, and progression of disease to the overall risk of hospital readmissions after major oncologic surgery.

The proposed plan of using readmission rates to assess hospital performance and of using them as a performance measure for reimbursement should be pursued with caution. Brown and colleagues perhaps states this best in an editorial with a well-worded analogy. They ask the readers to consider three potential outcomes from peritonitis: the patient gets better, the patient develops an abscess, or the patient dies. Development of an abscess, although costly and unfortunate, is a profoundly better outcome than death. This benefit should not be looked on as a failure and it would generally be considered unfair to punish a hospital and withhold payment because of an event that is part of a natural course of a disease process. As such, surgical complications are inherent risks associated with complex oncologic surgeries and may not be preventable and do lead to early postoperative readmissions.

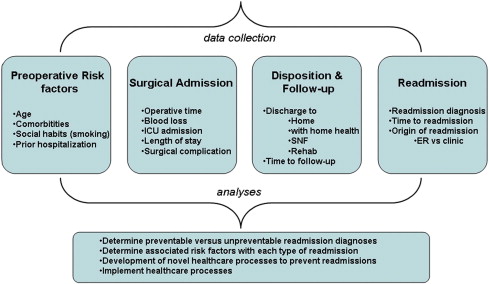

Large population-based data sets provide a comprehensive denominator for incidence, timing, and generalized reasons for readmission—the proverbial view from 30,000 feet. These studies are met, however, with several limitations that have been previously discussed. In the future, well-kept databases of detailed information at the individual hospital level will be necessary to assess a causal relationship between the specific hospital care delivered and the risk of readmission. Developing a framework for readmission data collection will be necessary for this research to progress. Given the review of the literature presented, the authors suggest the following four categories of readmission data be collected at the institutional level: (1) preoperative risk factors, (2) surgical admission data, (3) discharge disposition and follow up, and (4) readmission data ( Fig. 1 ). Once this data is collected, it will be up to local experts to analyze it and determine if a readmission diagnosis is preventable or unpreventable. The factors from the four categories that are associated with potentially preventable readmissions should lead to development and implementation of novel processes aimed at decreasing readmissions.