Understanding and Preventing Infectious Diseases

Despite improved treatment and prevention strategies, including powerful antibiotics, complex vaccines, and modern sanitation practices, infection continues to cause a great deal of serious illness throughout the world—even in highly industrialized countries. In developing countries, infection remains a critical health problem.

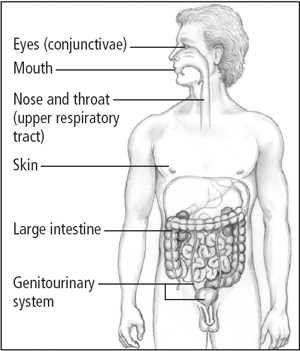

Large numbers of microorganisms exist in the air we breathe, on the surfaces we touch, and on and within our bodies. Microorganisms naturally found on and within the body are called normal flora—they concentrate in certain body regions, such as the skin, mouth, and GI tract. The skin harbors more than 10,000 microorganisms/cm2. Scrapings from the surface of the teeth or gums may show millions of organisms per milligram of tissue.

The human body and its normal flora coexist in a sort of ecosystem whose equilibrium is essential to good health. Under normal circumstances, these microorganisms are nonpathogenic and harmless. In fact, they may aid the body by competing for nutrients with disease-producing microorganisms or by performing special tasks. For example, the lumen of the bowel contains microorganisms that carry out many chemical functions. Moreover, disruption of the normal ecology of the microbial flora can pose substantial risks to the host. (See Where normal flora live.)

Relatively few of the many species of microorganisms that exist become adapted to the unique environments of various body tissue. Thus, to a certain degree, the flora of a given species—even of specific body tissue—is predictable.

Infection is the invasion and multiplication in or on body tissue of microorganisms that produce signs and symptoms along with an immune response. Such reproduction injures the host either by causing cellular damage from microorganism-produced toxins or intracellular multiplication or by competing with host metabolism. The host’s own immune response may increase tissue damage, which may be localized (as in infected pressure ulcers) or systemic. The very young and the very old are most susceptible to infections.

Microorganisms that cause infectious diseases are difficult to overcome for many reasons:

Some bacteria develop a resistance to antibiotics.

Some microorganisms, such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), include many different strains, and a single vaccine can’t provide protection against them all.

Most viruses resist antiviral drugs.

Some microorganisms localize in areas that make treatment difficult, such as the central nervous system and bone.

New infectious agents, such as HIV and severe acute respiratory syndrome–corona-virus, occasionally arise.

Opportunistic microorganisms can cause infections in immunocompromised patients.

Much of the world’s ever-growing population has not received immunizations.

Increased air travel by the world’s population can speed a virulent microorganism to a heavily populated urban area within hours.

Biological warfare and bioterrorism with organisms such as anthrax, plague, and smallpox are an increasing threat to public health and safety throughout the world.

Invasive procedures and the expanded use of immunosuppressive drugs increase the risk of infection for many. (See When microorganisms grow resistant, page 4.)

Also, certain factors that normally contribute to improved health, such as good nutrition, clean living conditions, and advanced medical care, can actually lead to increased risk for infection. For example, travel can expose people to diseases against which they have little natural immunity. The increased use of immunosuppressants, as well as surgery and other invasive procedures, also heighten the risk for infection. (See Sporadic, epidemic, or endemic, page 5.)

Types of Infection

Microorganisms responsible for infectious diseases include bacteria, viruses, fungi (yeasts and molds), and parasites.

Bacteria are single-cell microorganisms with well-defined cell walls that can grow independently on artificial media without the need for other cells. Bacteria inhabit the intestines of humans and other animals as normal flora used in the digestion of food. Also found in soil, bacteria are vital to soil fertility. These microorganisms break down dead tissue, which allows the tissue to be used by other organisms.

Despite the many types of known bacteria, only a small number are harmful to humans. In developing countries, where poor sanitation increases the risk of infection, bacterial diseases commonly cause death and disability. In industrialized countries, bacterial infections are the most common fatal infectious diseases.

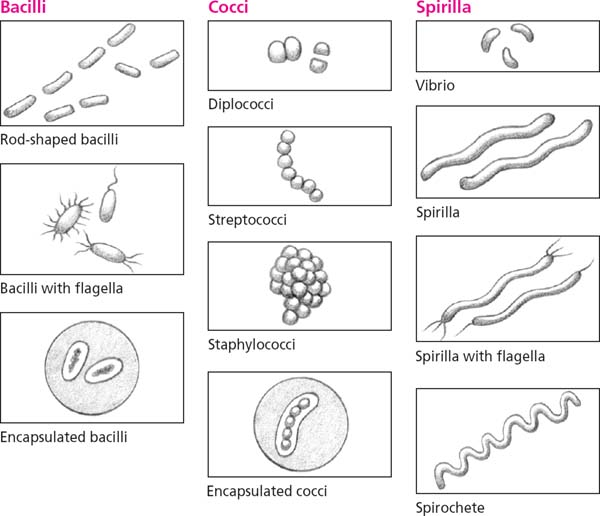

Bacteria are classified by shape. Spherical bacterial cells are called cocci; rod-shaped bacteria, bacilli; and spiral-shaped bacteria, spirilla. Bacteria are also classified according to their response to staining (gram-positive, gram-negative, or acid-fast bacteria); their motility (motile or nonmotile bacteria); their tendency toward encapsulation (encapsulated or nonencapsulated bacteria); and their capacity to form spores (sporulating or nonsporulating bacteria). (See Comparing bacterial shapes, page 6.) Viruses are subcellular organisms made up only of a ribonucleic acid or a deoxyribonucleic acid nucleus covered with proteins. They’re the smallest known organisms, so tiny they’re visible only through an electron microscope. Viruses can’t replicate independent of host cells. Rather, they invade a host cell and stimulate it to participate in the formation of additional virus particles. The estimated 400 viruses that infect humans are classified according to their size, shape (spherical, rod-shaped, or cubic), or means of transmission (respiratory, fecal, oral, or sexual). (See Viral infection of a host cell, page 7.)

Fungi are single-cell organisms whose nuclei are enveloped by nuclear membranes. They have rigid cell walls like plant cells but lack chlorophyll, the green matter necessary for photosynthesis. They also show relatively little cellular specialization. Fungi occur as yeasts (single-cell, oval-shaped organisms) or molds (organisms with hyphae, or branching filaments). Depending on the environment, some fungi may occur in both forms. Fungal diseases in humans are called mycoses.

Parasites are unicellular or multicellular organisms that live in or on their hosts and are dependent on the host for nourishment. They usually only take the nutrients they need and rarely kill their hosts, although they can cause harm. Parasites are divided into two types, depending on their relationship with the host: Endoparasites live inside the

host (for example, protozoans, worms, flukes, and amoebae), while ectoparasites live on the host’s skin (such as fleas, ticks, and lice).

host (for example, protozoans, worms, flukes, and amoebae), while ectoparasites live on the host’s skin (such as fleas, ticks, and lice).

Over the past few decades, many microorganisms have developed resistant strains—those that won’t succumb to the antibiotics normally used to combat them. Resistant strains pose serious problems for health care facilities and for the general population because the infections are becoming increasingly more difficult to treat.

Reasons for Resistant Strains

Practices by health care professionals, patients, and certain industries have contributed to the emergence of resistant bacterial strains. Such practices include:

Unnecessary use of antibiotics

Inappropriate prescribing of antibiotics (such as prescribing a drug that doesn’t specifically combat the infecting organism)

Patient failure to complete the full prescribed course of antibiotics

Use of antibiotics in animal feed

Contributing to the problem are easy access to over-the-counter antibiotics (in some countries) and symptomless carriers who harbor and spread resistant microorganisms.

From Adaptation to Resistance

A microorganism develops resistance by continuously adapting to its changing environment in an effort to survive. Through adaptation, some microorganisms have developed the ability to enzymatically destroy an antibiotic, such as by inducing cellular or metabolic changes in target areas. Some bacteria decrease cellular intake of a drug. Others have receptor sites on the bacteria that have less attraction for a drug. New strains of gonococci emerging during the past 25 years are resistant to the antibiotics typically recommended for treating gonorrhea. Penicillin was the drug of choice until a resistant strain developed in 1976; tetracycline-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae emerged in 1986. Consequently, eradicating endemic antibiotic-resistant gonorrhea is now difficult.

Hereditary Resistance

Hereditary drug resistance is commonly carried by extrachromosomal genetic elements with cell resistance factors. These factors can be transferred among bacterial cells in a population and between different, but closely related, bacterial populations.

Effects of Hospitalization

Lengthy hospital stays and frequent hospitalization place some patients at special risk for drug-resistant infections. Most vulnerable are the very young, the very old, the seriously ill, and those requiring invasive equipment. Many of these patients already have weakened immune systems, making them even more susceptible.

Antibiotic Therapy

Persons already taking antibiotics are at an increased risk of infection by resistant microorganisms because the antibiotic kills off susceptible microorganisms, allowing resistant strains to take hold.

Striking Back

When an outbreak of a resistant microorganism occurs, researchers use molecular typing techniques to identify the microorganism, track it to the source, and contain it. Medicine has managed to stay just ahead of resistant microorganisms. Recently, however, some microorganisms have emerged that are resistant to all antibiotics. Some experts even fear that most infections may eventually result from drug-resistant micro-organisms.

How Infection Occurs

Whether or not an infection develops hinges on variables relating to three crucial factors:

An infectious organism (pathogen)

A host (any organism that can support the nutritional and physical growth of another organism)

A favorable environment

As long as one of these factors is missing, infection does not occur. However, if an

imbalance develops—for example, if a patient’s immune system is suppressed and can’t fight off pathogens—the potential for infection increases.

imbalance develops—for example, if a patient’s immune system is suppressed and can’t fight off pathogens—the potential for infection increases.

To determine whether an infection problem exists in a particular health care facility or geographic area, investigators study the current incidence of the disease in that facility or area and compare it with past incidence rates.

Sporadic Diseases

If investigators find cases occurring occasionally and irregularly with no specific pattern, they classify the infection as sporadic. Examples of diseases that typically occur sporadically are tetanus and gas gangrene.

Epidemic Diseases

If a greater-than-expected number of cases of a given disease arise suddenly in a specific area over a specific period, investigators label it an epidemic. A highly publicized epidemic occurred during an American Legion convention in Philadelphia in 1976, resulting in the naming of a new illness, Legionnaire’s disease.

A pandemic is an epidemic that affects several countries or continents. A current example is the H1N1 influenza pandemic.

Endemic Diseases

Endemic diseases are those that are present in a population or community at all times. They usually involve relatively few people during a specified time. Hepatitis B, for example, is endemic in certain Asian cultures.

Herd Immunity

When a high proportion of a population has developed immunity to a specific infectious agent, herd immunity exists. For example, thanks to the measles vaccine, the population of the United States has herd immunity to measles, and most Americans are able to resist it.

Infection starts when a microorganism invades body tissue. Once the microorganism breaches the patient’s immune defenses and enters the body, it multiplies and causes harmful effects. The severity of the infection depends on such factors as microbial characteristics, the number of microorganisms present, and the way in which the microorganisms enter the body and spread. (See The fragile chain of infection, pages 8–9.)

The Inflammatory Response

The body reacts to microbial invasion by producing an inflammatory response. The five classic signs and symptoms of inflammation are as follows:

Redness—Caused by dilation of arterioles and increased circulation to the site; a localized blush caused by filling of previously empty or partially distended capillaries

Pain—Results from stimulation of pain receptors by swollen tissue, local pH changes, and chemicals excreted during the inflammatory process

Heat—Caused by local vasodilation, fluid leakage into the interstitial spaces, and increased blood flow to the area

Swelling—Caused by local vasodilation, leakage of fluid into interstitial spaces, and blockage of lymphatic drainage

Loss of function—Results primarily from pain and edema

Other manifestations of the inflammatory response include fever, malaise, nausea, vomiting, and purulent discharge from wounds.

Not all infections are apparent or symptomatic. With subclinical, or asymptomatic, infection, the infectious microorganism is present and an immune system response is initiated, but the person shows no signs or symptoms of the disease. (See Types of infection, page 10.)

Endogenous and Exogenous Microorganisms

Microorganisms may be endogenous or exogenous. Endogenous microorganisms are those found on the skin and in such body substances as saliva, feces, and sputum. They can cause disease in a susceptible individual.

Exogenous microorganisms originate from sources outside the body. Humans and exogenous microorganisms usually live together in harmony. However, if something disrupts this harmonious relationship, the microorganisms may cause infection.

Invasion and Colonization

The presence of microorganisms in or on an individual is called colonization. Colonized microorganisms grow and multiply but may not invade tissue and thus don’t produce cellular injury. In cases of colonization, tissue culture results are positive but the patient lacks evidence of infection.

However, some people who are colonized with bacteria do develop localized signs and symptoms of infection—tenderness, swelling, redness, and pus—because the bacteria has invaded the tissue, producing cellular injury. A culture of the pus typically elicits the microorganism. Colonized bacteria may also cause systemic infection, producing fever, an elevated white blood cell count, and possibly shock.

Pathogenicity

Pathogenicity refers to a microorganism’s ability to cause pathogenic changes, or

disease. An example of a highly pathogenic microorganism is the rabies virus, which always causes clinical disease in the host. In contrast, alpha-hemolytic streptococci have low pathogenicity; although they commonly colonize humans, they rarely produce clinical disease. Factors affecting pathogenicity include the microorganism’s mode of action, virulence, dose, invasiveness, toxigenicity, specificity, viability, and antigenicity.

disease. An example of a highly pathogenic microorganism is the rabies virus, which always causes clinical disease in the host. In contrast, alpha-hemolytic streptococci have low pathogenicity; although they commonly colonize humans, they rarely produce clinical disease. Factors affecting pathogenicity include the microorganism’s mode of action, virulence, dose, invasiveness, toxigenicity, specificity, viability, and antigenicity.

MODE OF ACTION. The means by which a microorganism produces disease is called its mode of action. Viruses, for example, cause infection by invading host cells and interfering with cell metabolism. Other modes of microbial action include:

Evasion or destruction of host defenses by preventing host phagocytes (scavenger cells) from engulfing and digesting them (used by Klebsiella pneumoniae)

Secretion of enzymes or toxins, which allows the microorganism to penetrate and spread through host tissue (used by the measles virus)

Production of toxins that interfere with intercellular responses (used by tetanus bacilli)

Stimulation of a pathologic immune response (used by group A beta-hemolytic streptococci)

Destruction of T-helper lymphocytes (used by HIV). (See Stages of infection, page 11.)

VIRULENCE. Virulence refers to the degree of a microorganism’s pathogenicity. Virulence can vary with the condition of the body’s defenses. For instance, Mycobacterium avium–intracellulare, bacteria commonly found in water and soil, can cause severe pulmonary and systemic disease in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome but typically do not cause illness in those with a normal immune system. Virulence can be enhanced by several factors:

Toxins produced by bacteria such as Streptococcus and Clostridium

The ability of microorganisms to elude host defenses (such as Pneumococcus with its polysaccharide capsule)

Persistence in the environment (spores and cysts)

Genetic variation (influenza)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree