Uncommon neoplasms of the anal canal are associated with significant diagnostic dilemma in clinical practice and a high index of suspicion and pathologic expertise is needed. The incidence is likely to increase, particularly of small, incidental lesions found because of use of more frequent colonoscopy and high-definition MRI. Generally treatment follows that of the same histologic subtype in other anatomic location. Surgical intervention is the cornerstone for cure in early/localized disease; however, removal of the anal canal is associated with significant morbidities and quality of life issues. A centralized global registry/database established under the auspices of the International Rare Care Initiative collaboration would be useful.

Key points

- •

Unusual cases of anal cancer comprise histologies of anal gland and canal adenocarcinoma, anal lymphoma, anal neuroendocrine tumors, and anal melanomas.

- •

Incidence is likely to rise with the greater use of colonoscopy and better imaging techniques, such as MRI.

- •

Management is based on usual treatment of underlying tumor type rather than that of anal epithelioid cancer.

- •

Improvements in outcome may result from an effort to collect rare cases of anal cancer on an international database.

Anal cancer is a rare disease with epidermoid cancers accounting for 1% to 2% of all digestive tract malignancies. Less common anal neoplasms comprise approximately 20% to 25% of these, including anal canal adenocarcinoma, anorectal melanoma, mesenchymal and neurogenic tumors of the anal canal (in particular gastrointestinal stromal tumors [GIST], schwannomas, and sarcomas), neuroendocrine tumors (NETs), lymphoma, and basal cell carcinoma (BCC). The anal canal is also a rare site for metastasis from other primary malignancies. As imaging technology improves, particularly MRI, and colonoscopy becomes routine, many rarer tumors are detected incidentally. Diligent linkage of clinical features with expert histopathology assessment identifies uncommon anal neoplasms to ensure that appropriate management is instituted.

Adenocarcinoma of the anal canal

Adenocarcinoma of the anal canal (ACA) accounts for 5% to 19% of all anal canal cancers. These are subclassified under the World Health Organization Classification of Tumors into three main subtypes: (1) colorectal-type adenocarcinoma, (2) anal gland adenocarcinoma, and (3) fistula-associated adenocarcinoma. In addition, a form of intraepithelial adenocarcinoma, also known as Paget disease, is a distinct entity and affects areas with a high density of apocrine glands around the anogenital region.

The clinical signs of adenocarcinoma, such as anal squamous cell anal cancer (SCC), are often nonspecific and the diagnosis is commonly made serendipitously in patients undergoing excision of presumed benign conditions. Management of ACA is challenging because of its rarity, difficulty in confirming diagnosis, and lack of direct evidence for particular clinical management strategies. There is little information regarding risk factors; however, there is some linkage to high-risk subtypes of human papilloma virus, mainly subtype 18.

Colorectal-Type Adenocarcinoma

These tumors represent either downward spread of a primary rectal adenocarcinoma (RA) or de novo carcinoma arising in residual glandular cells of the anal transition zone just above the dentate line. In contrast to a rectal-based adenocarcinoma, there is a higher risk of inguinal and femoral nodal involvement because of the dual lymphatic drainage of the anus. Histologically and clinically these cancers are indistinguishable from usual rectal tumors and apart from their anatomic location do not represent a special entity. In most cases the histologic diagnosis is straightforward. However, on immunohistochemistry, colorectal-type ACA may have unexpected cytokeratin (CK) 7 expression, although this is usually accompanied by coexpression of CK20. This is different from anal gland carcinomas, which usually are CK20 negative.

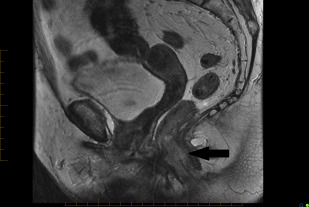

In practice, tumors used to be classified as rectal cancers on digital examination if their epicenter was located greater than 2 cm proximal to the dentate line or the anorectal ring, and as anal canal cancers if their epicenter was less than 2 cm below the dentate line. Newer imaging techniques, such as MRI, assist with delineating site of origin more accurately, particularly if there is a polypoid stalk ( Figs. 1 and 2 ).

Anal Gland Adenocarcinoma

Anal gland tumors usually originate from the anal ducts and demonstrate continuity with the anal gland epithelium. There are only a few case reports demonstrating convincing evidence of the origin of the tumor from an anal gland. These tumors are sometimes termed as “anal duct adenocarcinoma” because of their putative origin and are characterized histologically by the combination of ductal and mucinous areas. Hobbs and colleagues defined the following criteria: cells haphazardly dispersed, invading the wall of the anorectal area, containing small glands with little mucin production and without an intraluminal component; and immune-histochemical positivity for CK7. Kuroda and colleagues have demonstrated that CK7, CK19, and MUC5AC immune-histochemical reactivity is a marker for adenocarcinoma of anal gland origin. In clinical practice, if tumor is present within the anal canal wall, without a pre-existing fistula or dysplasia of the surface mucosa, then irrespective of the extent of mucin production it is more likely to be anal gland adenocarcinoma.

Adenocarcinoma Within Anorectal Fistula

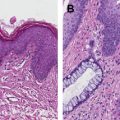

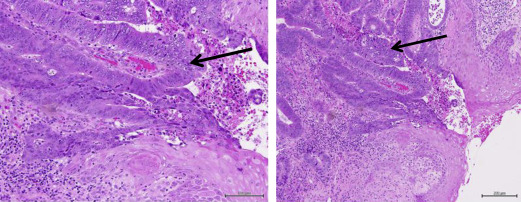

Anorectal fistulae may be developmental or acquired secondary to underlying inflammatory bowel disease, such as Crohn disease. Adenocarcinomas arising in anorectal fistulae usually have the histologic appearance of a well-differentiated mucinous adenocarcinoma; however, tubular adenocarcinomas and squamous cell neoplasia can also be present ( Fig. 3 ). The cell of origin could be related to either rectal-type glandular mucosa or anal glands or ducts. Occasionally there is evidence of epithelioid granulomas secondary to inflammation or extravasated mucin, in the absence of other signs of underlying inflammatory bowel disease. Rarely, adenocarcinomas can arise in congenital duplications of the lower part of the hindgut, which can be lined by rectal mucosa that has a tendency to become malignant.

Management of Anal Adenocarcinoma

Locoregional disease

Importantly, the management of adenocarcinomas arising in the anal canal follows the same principles as rectal cancer, rather than SCC anus. The primary treatment is surgical resection, typically abdominoperineal resection (APR) because sphincter preservation is not achievable. The literature supports surgical resection as providing the lowest rates of local relapse, recognizing that with historical data sets there is inevitable selection bias. Based on limited data, survival rates seem to be improved with multimodality management with chemotherapy and radiotherapy given before or after surgery, with improvement in local and systemic control. For anal adenocarcinoma, data exist for benefit from radiation therapy given either neoadjuvantly or adjuvantly for T3-4 and N1-2 stage, as per rectal cancer. Intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) and Volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT) techniques are recommended and treatment volume should reflect the lymphatic drainage of the anus, including inguinal lymph nodes.

Prognosis

Only limited case series have been reported. The most recent data from a Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results database review from 1990 to 2011 compared survival of patients diagnosed with ACA, anal SCC, and RA. Median overall survival (OS) of patients with ACA was 33 months, compared with SCC of 118 months and RA of 68 months ( P <.01). Multivariate analysis demonstrated that ACA had worse prognosis than SCC (hazard ratio, 0.66; 95% confidence interval, 0.59–0.75; P <.01) and RA (hazard ratio, 0.68; 95% confidence interval, 0.61–0.77; P <.01). Improved survival was observed in patients who underwent radical surgery (hazard ratio, 0.71; 95% confidence interval, 0.51–1.00; P = .05).

The importance of resection of adenocarcinomas arising in the anal canal was demonstrated in a retrospective series from MD Anderson Cancer Center in which 16 patients were treated between 1976 and 1998 with either primary radiotherapy or definitive chemoradiation (no surgery). When compared stage for stage with 92 patients with SCC treated with definitive chemoradiation, patients with ACA had a higher 5-year local recurrence rate (18% for SCC vs 54% for ACA) and worse disease-free survival (DFS) (77% vs 19%, respectively) and 5-year OS (85% vs 64%).

A multicenter retrospective study (1974–2000) from the Rare Cancer Network compared 82 patients treated with different modalities. The 5-year actuarial local relapse rate was 20% for APR (n = 6), 37% for radiotherapy plus surgery (n = 45), and 36% for definitive chemoradiation (n = 31). The 5-year OS was 21%, 29%, and 58%, respectively; 5-year DFS was 22%, 25%, and 54%. Such data support the role of radiotherapy and raise the potential of definitive chemoradiation allowing sphincter preservation.

Metastatic disease

As with local therapy, management of metastatic disease follows the protocols used for colorectal cancer. Combination or single-agent palliative chemotherapy is used to prolong survival and improve local control and quality of life (QoL). There is paucity of data informing the choice of chemotherapy regimens or the role of newer targeted drugs. Overall outcome seems to be worse than patients with metastatic colorectal cancer.

Adenocarcinoma of the anal canal

Adenocarcinoma of the anal canal (ACA) accounts for 5% to 19% of all anal canal cancers. These are subclassified under the World Health Organization Classification of Tumors into three main subtypes: (1) colorectal-type adenocarcinoma, (2) anal gland adenocarcinoma, and (3) fistula-associated adenocarcinoma. In addition, a form of intraepithelial adenocarcinoma, also known as Paget disease, is a distinct entity and affects areas with a high density of apocrine glands around the anogenital region.

The clinical signs of adenocarcinoma, such as anal squamous cell anal cancer (SCC), are often nonspecific and the diagnosis is commonly made serendipitously in patients undergoing excision of presumed benign conditions. Management of ACA is challenging because of its rarity, difficulty in confirming diagnosis, and lack of direct evidence for particular clinical management strategies. There is little information regarding risk factors; however, there is some linkage to high-risk subtypes of human papilloma virus, mainly subtype 18.

Colorectal-Type Adenocarcinoma

These tumors represent either downward spread of a primary rectal adenocarcinoma (RA) or de novo carcinoma arising in residual glandular cells of the anal transition zone just above the dentate line. In contrast to a rectal-based adenocarcinoma, there is a higher risk of inguinal and femoral nodal involvement because of the dual lymphatic drainage of the anus. Histologically and clinically these cancers are indistinguishable from usual rectal tumors and apart from their anatomic location do not represent a special entity. In most cases the histologic diagnosis is straightforward. However, on immunohistochemistry, colorectal-type ACA may have unexpected cytokeratin (CK) 7 expression, although this is usually accompanied by coexpression of CK20. This is different from anal gland carcinomas, which usually are CK20 negative.

In practice, tumors used to be classified as rectal cancers on digital examination if their epicenter was located greater than 2 cm proximal to the dentate line or the anorectal ring, and as anal canal cancers if their epicenter was less than 2 cm below the dentate line. Newer imaging techniques, such as MRI, assist with delineating site of origin more accurately, particularly if there is a polypoid stalk ( Figs. 1 and 2 ).

Anal Gland Adenocarcinoma

Anal gland tumors usually originate from the anal ducts and demonstrate continuity with the anal gland epithelium. There are only a few case reports demonstrating convincing evidence of the origin of the tumor from an anal gland. These tumors are sometimes termed as “anal duct adenocarcinoma” because of their putative origin and are characterized histologically by the combination of ductal and mucinous areas. Hobbs and colleagues defined the following criteria: cells haphazardly dispersed, invading the wall of the anorectal area, containing small glands with little mucin production and without an intraluminal component; and immune-histochemical positivity for CK7. Kuroda and colleagues have demonstrated that CK7, CK19, and MUC5AC immune-histochemical reactivity is a marker for adenocarcinoma of anal gland origin. In clinical practice, if tumor is present within the anal canal wall, without a pre-existing fistula or dysplasia of the surface mucosa, then irrespective of the extent of mucin production it is more likely to be anal gland adenocarcinoma.

Adenocarcinoma Within Anorectal Fistula

Anorectal fistulae may be developmental or acquired secondary to underlying inflammatory bowel disease, such as Crohn disease. Adenocarcinomas arising in anorectal fistulae usually have the histologic appearance of a well-differentiated mucinous adenocarcinoma; however, tubular adenocarcinomas and squamous cell neoplasia can also be present ( Fig. 3 ). The cell of origin could be related to either rectal-type glandular mucosa or anal glands or ducts. Occasionally there is evidence of epithelioid granulomas secondary to inflammation or extravasated mucin, in the absence of other signs of underlying inflammatory bowel disease. Rarely, adenocarcinomas can arise in congenital duplications of the lower part of the hindgut, which can be lined by rectal mucosa that has a tendency to become malignant.

Management of Anal Adenocarcinoma

Locoregional disease

Importantly, the management of adenocarcinomas arising in the anal canal follows the same principles as rectal cancer, rather than SCC anus. The primary treatment is surgical resection, typically abdominoperineal resection (APR) because sphincter preservation is not achievable. The literature supports surgical resection as providing the lowest rates of local relapse, recognizing that with historical data sets there is inevitable selection bias. Based on limited data, survival rates seem to be improved with multimodality management with chemotherapy and radiotherapy given before or after surgery, with improvement in local and systemic control. For anal adenocarcinoma, data exist for benefit from radiation therapy given either neoadjuvantly or adjuvantly for T3-4 and N1-2 stage, as per rectal cancer. Intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) and Volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT) techniques are recommended and treatment volume should reflect the lymphatic drainage of the anus, including inguinal lymph nodes.

Prognosis

Only limited case series have been reported. The most recent data from a Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results database review from 1990 to 2011 compared survival of patients diagnosed with ACA, anal SCC, and RA. Median overall survival (OS) of patients with ACA was 33 months, compared with SCC of 118 months and RA of 68 months ( P <.01). Multivariate analysis demonstrated that ACA had worse prognosis than SCC (hazard ratio, 0.66; 95% confidence interval, 0.59–0.75; P <.01) and RA (hazard ratio, 0.68; 95% confidence interval, 0.61–0.77; P <.01). Improved survival was observed in patients who underwent radical surgery (hazard ratio, 0.71; 95% confidence interval, 0.51–1.00; P = .05).

The importance of resection of adenocarcinomas arising in the anal canal was demonstrated in a retrospective series from MD Anderson Cancer Center in which 16 patients were treated between 1976 and 1998 with either primary radiotherapy or definitive chemoradiation (no surgery). When compared stage for stage with 92 patients with SCC treated with definitive chemoradiation, patients with ACA had a higher 5-year local recurrence rate (18% for SCC vs 54% for ACA) and worse disease-free survival (DFS) (77% vs 19%, respectively) and 5-year OS (85% vs 64%).

A multicenter retrospective study (1974–2000) from the Rare Cancer Network compared 82 patients treated with different modalities. The 5-year actuarial local relapse rate was 20% for APR (n = 6), 37% for radiotherapy plus surgery (n = 45), and 36% for definitive chemoradiation (n = 31). The 5-year OS was 21%, 29%, and 58%, respectively; 5-year DFS was 22%, 25%, and 54%. Such data support the role of radiotherapy and raise the potential of definitive chemoradiation allowing sphincter preservation.

Metastatic disease

As with local therapy, management of metastatic disease follows the protocols used for colorectal cancer. Combination or single-agent palliative chemotherapy is used to prolong survival and improve local control and quality of life (QoL). There is paucity of data informing the choice of chemotherapy regimens or the role of newer targeted drugs. Overall outcome seems to be worse than patients with metastatic colorectal cancer.

Paget disease of the anal canal

Paget disease of anal canal falls under the extramammary Paget disease group and was first described by Crocker in 1889. It most commonly occurs in elderly patients and manifests as red or white-crusted patches of skin with associated pruritus in the anal region. Paget disease can also occur in other anogenital sites, most commonly in vulval skin, perineum, and anal margin skin. Primary Paget disease of the anus takes its origin from the epidermis or squamous epithelium and may not always evolve into an invasive lesion. In contrast, secondary Paget disease is often linked to an underlying visceral malignancy (eg, colorectal or ovarian carcinoma) and can either present synchronously or metachronously to the primary. Based on limited data, the incidence of synchronous visceral malignancy could be greater than 50% and should be excluded at diagnosis. Occasionally histologically pagetoid extension of cancer cells from an underlying anal or RA is seen in the overlying or immediately adjacent squamous epithelium.

Histologically, Paget disease is classically associated with hyperplastic changes in the involved squamous mucosal surface. Knowledge of such changes assists in making the diagnosis of Paget disease especially during frozen section procedures, to avoid the misdiagnosis of simple squamous dysplasia. There have been efforts to distinguish primary from secondary disease based on immunohistochemical phenotyping; however, data are limited to small case series. It seems that CK7 is a marker of Paget cells, irrespective of their site or an associated visceral malignancy. If it is associated with RA then cells are uniformly immunoreactive to CK20. CK20 expression is seen also in vulvar Paget disease. In those cases, GCDFP15 expression may be helpful; if positive it can lend support toward a nonrectal origin.

The management of Paget disease is usually surgical. The extent of treatment of noninvasive lesions is determined by preoperative mapping of the lesion and intraoperative confirmation by frozen sections to ascertain clear surgical margins. The prognosis of noninvasive Paget disease is good; however, local recurrence is often seen because of the presence of multifocal disease.

Locally invasive perianal Paget disease usually requires a radical surgical approach, although definitive chemoradiotherapy has also been used. Management of secondary Paget disease is directed toward the treatment of the underlying malignancy and these patients have a guarded prognosis.

Anorectal melanoma

Anorectal mucosal melanoma accounts for approximately 0.05% of all colorectal malignancies and 1% of all anal canal cancers. It originates in the rectum in 42% and anal canal in 33%, respectively, whereas the primary site cannot be determined in about 25%. Risk factors are not clearly defined apart from the association with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Unlike other mucosal melanomas, anorectal site is more common in whites and females with median age of diagnosis at 60 years. Patients typically present with bleeding or a mass, anorectal pain, or change in bowel habit. Occasionally, melanoma is an incidental pathologic finding after hemorrhoidectomy or anal polyp resection. Anorectal mucosal melanoma is pigmented in approximately one-third of cases and at presentation most lesions are greater than 2 mm thick. Regional lymph node involvement is seen in 60% of cases and distant metastases are present at diagnoses in about 30%.

Pathology and Staging

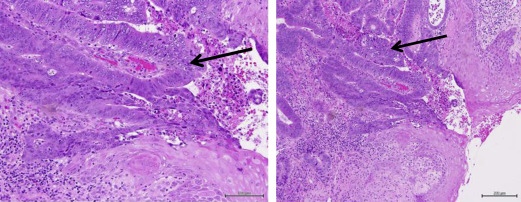

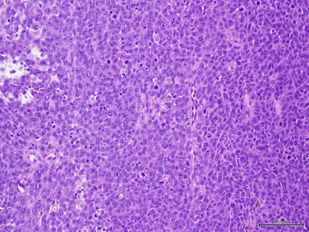

Overall 20% of mucosal melanomas are multifocal, compared with less than 5% of cutaneous melanomas and 40% are amelanotic. Histologic features are similar to cutaneous melanomas showing a junctional component adjacent to the invasive tumor, which also serves as evidence that the lesion is primary rather than metastatic ( Fig. 4 ). The desmoplastic variant may occasionally occur at this site. Diagnosis may be challenging and requires immunohistochemical confirmation with tumor cells expressing S-100, HMB-45, and melan A (see Fig. 4 ). Factors associated with poor prognosis are tumor size and thickness, regional lymph node involvement, presence of perineural invasion, and amelanotic subtype.

Anorectal melanoma is not addressed by the current American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system. Based on retrospective series, it is categorized as localized disease only, regional lymph node involvement, or distant metastases. Survival outcomes from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results database review of 183 patients treated for anorectal mucosal melanoma over a historic period (1973–2003) are presented in Table 1 .

| Stage a | Median Overall Survival, mo | Survival Rate, % |

|---|---|---|

| I (localized disease) | 24 | 26.7 |

| II (regional lymph node involved) | 17 | 9.8 |

| III (distant metastases) | 8 | 0 |

Management

Locoregional disease

The primary aim of surgery is for curative resection (wide excision) to achieve negative margins. If possible a sphincter-sparing excision is performed; occasionally APR is necessary for bulky disease or as salvage for patients with local but not systemic recurrence. The impact of the extent of resection on long-term outcome has been reported in a few retrospective case series only. Although there is some evidence lending support to upfront APR providing improved local control at the expense of higher morbidity and detriment to QoL and functional capacity, there is no evidence that more extensive surgery is associated with a better OS. There is no proven role for sentinel lymph node biopsy or elective bilateral inguinal lymph node dissection in the absence of clinical nodal disease.

Factors associated with a better outcome are R0 resection and tumor stage, based on the Swedish National Cancer Registry dataset. In a published series of 251 patients, the 5-year survival rates following an R0 resection were 19% compared with 6% where local excision was incomplete.

Adjuvant therapy

Adjuvant treatment to improve locoregional relapse rate or OS has not been prospectively studied; however, adjuvant radiotherapy is often added to improve local control. The MD Anderson Cancer Center has reported on a series of 54 patients treated during 1989 to 2008 with hypofractionated radiotherapy (25–30 Gy in 5–6 fractions over a 2- to 3-week period) following sphincter-sparing local excision. The radiation was added as an alternative to APR. This approach was associated with local control in 82% of patients with sphincter preservation in 92% but there was no demonstrable impact on OS, with only 30% alive at 5 years. The development of IMRT and VMAT techniques significantly reduces toxicity, which may increase its utility.

Systemic adjuvant therapy is not established in patients with mucosal melanoma. The only randomized evidence comes from a phase II study from China that enrolled 189 patients with resected mucosal melanoma. A total of 56 patients had anorectal melanoma and patients were randomized to observation (n = 21), 1 year of interferon alfa-2b (n = 17), or chemotherapy (n = 18; temozolomide plus cisplatin). The median DFS was significantly prolonged in the chemotherapy arm compared with interferon and observation (20.8 vs 9.4 vs 5.4 months, respectively) as was median OS (49 vs 40 vs 21 months). However, no data have been reported in Western populations.

Metastatic disease

Treatment is based on extrapolation from trials of metastatic cutaneous melanoma. Few patients with melanoma of mucosal origin were enrolled in the clinical trials of modern antimelanoma therapies, with specific exclusion criteria for primaries of mucosal origin.

Approximately 10% of mucosal melanomas harbor the BRAF v600E driver mutation and a further 25% have somatic mutations including 9% with KIT mutations in exon 11 or 13. Among all patients with mucosal melanoma with BRAF mutation, anorectal mucosal origin is the most common (20%) primary site.

Results from three small phase II trials evaluating the role of imatinib in advanced mucosal melanoma (no breakdown of site of origin stated) harboring somatic alterations of KIT demonstrate significant activity ( Table 2 ).