Hematopoietic cell transplantation is curative therapy for thalassemia major. Although the clinical application of hematopoietic cell transplantation has relied on marrow collected from related and unrelated donors as the primary source of donor hematopoietic cells, umbilical cord blood (UCB) is an alternative source of hematopoietic cells and represents a suitable allogeneic donor pool in the event that a marrow donor is not available. Progress in developing UCB transplantation for thalassemia is reviewed and the most likely areas of future clinical investigation are discussed.

After the initial demonstration nearly 30 years ago that bone marrow transplantation has curative potential for thalassemia major (discussed in the article by Gaziev and Lucarelli elsewhere in this issue), subsequent efforts have focused on methods to improve the safety of hematopoietic cell transplantation and to broaden its availability. These activities have included the investigation of alternative sources of hematopoietic stem cells that might be used in lieu of bone marrow. This effort was driven in part by the recognition that graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality after conventional marrow transplantation and that most individuals with thalassemia major lack an HLA-identical sibling donor. The possibility that umbilical cord blood (UCB) might help investigators achieve both objectives was first suggested by the report of successful UCB transplantation for another hereditary hematologic disorder, Fanconi anemia, in 1989. Since then, more than 20,000 transplantation procedures have been performed from unrelated donor UCB units, and more than 450,000 UCB units have been collected and banked by approximately 50 cord blood banks worldwide (reviewed by Rocha and Gluckman ). Although the bulk of the clinical application of UCB transplantation has been in the treatment of recurrent or refractory malignant hematologic disorders, UCB also has the potential to emerge as an important alternative source of donor hematopoietic cells in the treatment of thalassemia major. This possibility hinges on exploiting the favorable characteristics of UCB, which include a lowered incidence of GVHD and a rapid tempo of immune reconstitution after transplantation, and on establishing novel approaches to reduce the problem of graft rejection after UCB transplantation.

Characteristics of the UCB graft

UCB has several properties that make it an attractive alternative to marrow as a source of allogeneic cells for transplantation, particularly for nonmalignant disorders, such as thalassemia major, where GVHD offers no benefit. These advantages, as articulated in the review by Rocha and Locatelli, include a lower incidence and severity of acute and chronic GVHD; the possibility of extending the number of HLA-antigen mismatches to 1 to 2 of the 6 HLA loci currently considered in UCB transplantation; a lower risk of transmitting latent virus infections, such as cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus, in the harvested hematopoietic cell collection; the elimination of clinical risk to the donor during hematopoietic stem cell procurement procedures; and a higher frequency of rare HLA haplotype representation in the donor pool compared with bone marrow registries as a result of targeting UCB collections from under-represented ethnic minorities. These advantages are balanced by a disadvantage, however, which is a higher risk of graft rejection and delayed hematopoietic recovery after transplantation that can contribute to serious infections. This risk follows from the reduced number of hematopoietic progenitor cells contained in a typical UCB collection compared with marrow harvesting and from the possibility that the naive immune system in UCB translates into a blunted allogeneic effect elicited by donor T lymphocytes and that is required for overcoming host immunologic barriers to engraftment. This limitation is significant in thalassemia major because pretransplantation exposures to minor histocompatibility antigens by chronic red blood cell transfusions seem to contribute to a high rate of graft rejection after conventional bone marrow transplantation for thalassemia major. Thus, graft rejection is predicted to pose a significant barrier to the wider application of UCB transplantation for thalassemia major.

Graft rejection and UCB transplantation

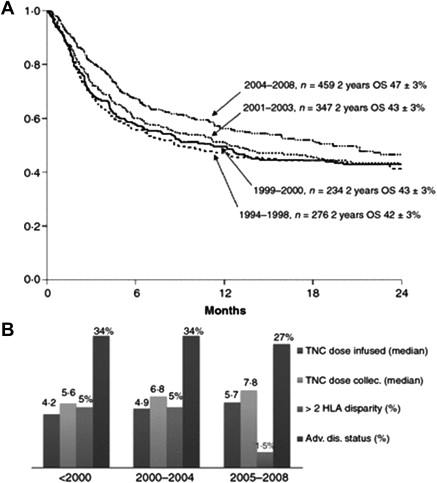

Several strategies have been used to mitigate the risk of graft rejection after UCB transplantation (discussed later). Almost all the published clinical series of unrelated donor UCB transplantation in children and adults with hematologic malignancies showed that the total nucleated cell (TNC) dose contained in a UCB unit has a profound impact on engraftment, as measured by preprocessing or the post-thaw TNC dose infused. Similarly, other direct measurements of the cellular content of the UCB unit, such as colony-forming unit activity and CD34+ cell content (a surrogate cell surface marker for the hematopoietic stem cell), were positively correlated with donor engraftment. An effect of TNC on other transplant-related complications, such as infection risk and survival, was also observed. In addition, the degree of HLA matching seemed to have an independent impact on outcome, with those recipients who had greater than 2 HLA mismatches experiencing the worst outcomes (the degree of matching in UCB transplantation is assessed by low-resolution HLA typing methods at HLA-A and HLA-B loci and by high-resolution at HLA-DRB1). The indication for UCB transplantation also had an impact on outcome, and those recipients with advanced-stage malignant diseases experienced the worst outcomes. As the factors that affect outcome became more widely appreciated, decision making about the selection of UCB donor units and suitable transplantation recipients was adjusted and these changes have improved outcomes over the past 2 decades, as assessed by the year the transplantation was conducted ( Fig. 1 ). In addition, improved supportive care and wider experience at individual centers also seem to have contributed to the improved outcomes.

Children who had nonmalignant disorders experienced a higher rate of graft rejection after UCB transplantation compared with those with a malignant disorder. In the setting of a nonmalignant disorder, the degree of HLA matching also influenced the probability of engraftment. This effect was more important in children with nonmalignant disorders compared with those malignant disorders, because a higher of incidence of GVHD associated with HLA mismatching translated into a graft-versus-malignancy effect that lowered the risk of relapse after UCB transplantation. For this reason, the degree of HLA matching (that is, 0, 1, or 2 HLA antigen mismatches) does not seem to influence the outcome in children with acute leukemia. In the nonmalignant disorders, however, HLA mismatching had a major impact on the incidence and severity of GVHD, engraftment, and survival, which was only partially overcome by increasing the cell dose. Based on Eurocord data that included 1204 UCB transplant recipients with malignant (N = 925) and nonmalignant (N = 279) conditions, the outcome after UCB transplantation was unacceptably poor in nonmalignant disease recipients who received a TNC dose less than 3.5 × 10 7 /kg and if HLA matching occurred at 4 of 6 HLA antigens. For this reason, optimizing the TNC dose in the UCB unit is generally agreed on as a key component in the decision-making process that precedes transplantation.

The cell dose limitation is particularly difficult to overcome in adult recipients and was a principal reason why UCB transplantation initially was restricted to children during its early development. In an effort to expand UCB transplantation, the transplantation team in Minneapolis reasoned that using 2 UCB units might facilitate engraftment and mitigate the difficulties associated with delayed engraftment or nonengraftment when also preceded by the application of a reduced intensity preparative regimen. A target cell dose of 3 × 10 7 TNC/kg recipient weight was achieved in 85% of the study participants by identifying 2 UCB units that were matched at 4 of 6 HLA antigens with the recipient and 3 of 6 HLA antigens between the 2 UCB units. Of 110 patients with hematologic diseases who were treated, 92% experienced neutrophil engraftment a median of 12 days after transplantation. More recently, outcomes after consecutive UCB transplantation in 155 adult recipients with hematologic malignancies were analyzed. In this cohort that also received a reduced intensity conditioning regimen, 38% received transplantation with 2 UCB units to fulfill minimum cell dose targets. Eighty percent of the patients had a neutrophil recovery greater than 500/mm 3 by 60 days after transplantation and 14% experienced graft rejection and autologous recovery of hematopoiesis. The factors associated with a better rate of neutrophil recovery included an elevated CD34+ cell dose, HLA compatibility, and having received a previous autologous stem cell transplantation. Together, these series show that it is possible to use 2 UCB units when the UCB cell content is otherwise limiting and that the cell dose and HLA compatibility are key factors that influence the engraftment of donor cells, particularly in recipients with nonmalignant hematologic disorders.

Graft rejection and UCB transplantation

Several strategies have been used to mitigate the risk of graft rejection after UCB transplantation (discussed later). Almost all the published clinical series of unrelated donor UCB transplantation in children and adults with hematologic malignancies showed that the total nucleated cell (TNC) dose contained in a UCB unit has a profound impact on engraftment, as measured by preprocessing or the post-thaw TNC dose infused. Similarly, other direct measurements of the cellular content of the UCB unit, such as colony-forming unit activity and CD34+ cell content (a surrogate cell surface marker for the hematopoietic stem cell), were positively correlated with donor engraftment. An effect of TNC on other transplant-related complications, such as infection risk and survival, was also observed. In addition, the degree of HLA matching seemed to have an independent impact on outcome, with those recipients who had greater than 2 HLA mismatches experiencing the worst outcomes (the degree of matching in UCB transplantation is assessed by low-resolution HLA typing methods at HLA-A and HLA-B loci and by high-resolution at HLA-DRB1). The indication for UCB transplantation also had an impact on outcome, and those recipients with advanced-stage malignant diseases experienced the worst outcomes. As the factors that affect outcome became more widely appreciated, decision making about the selection of UCB donor units and suitable transplantation recipients was adjusted and these changes have improved outcomes over the past 2 decades, as assessed by the year the transplantation was conducted ( Fig. 1 ). In addition, improved supportive care and wider experience at individual centers also seem to have contributed to the improved outcomes.

Children who had nonmalignant disorders experienced a higher rate of graft rejection after UCB transplantation compared with those with a malignant disorder. In the setting of a nonmalignant disorder, the degree of HLA matching also influenced the probability of engraftment. This effect was more important in children with nonmalignant disorders compared with those malignant disorders, because a higher of incidence of GVHD associated with HLA mismatching translated into a graft-versus-malignancy effect that lowered the risk of relapse after UCB transplantation. For this reason, the degree of HLA matching (that is, 0, 1, or 2 HLA antigen mismatches) does not seem to influence the outcome in children with acute leukemia. In the nonmalignant disorders, however, HLA mismatching had a major impact on the incidence and severity of GVHD, engraftment, and survival, which was only partially overcome by increasing the cell dose. Based on Eurocord data that included 1204 UCB transplant recipients with malignant (N = 925) and nonmalignant (N = 279) conditions, the outcome after UCB transplantation was unacceptably poor in nonmalignant disease recipients who received a TNC dose less than 3.5 × 10 7 /kg and if HLA matching occurred at 4 of 6 HLA antigens. For this reason, optimizing the TNC dose in the UCB unit is generally agreed on as a key component in the decision-making process that precedes transplantation.

The cell dose limitation is particularly difficult to overcome in adult recipients and was a principal reason why UCB transplantation initially was restricted to children during its early development. In an effort to expand UCB transplantation, the transplantation team in Minneapolis reasoned that using 2 UCB units might facilitate engraftment and mitigate the difficulties associated with delayed engraftment or nonengraftment when also preceded by the application of a reduced intensity preparative regimen. A target cell dose of 3 × 10 7 TNC/kg recipient weight was achieved in 85% of the study participants by identifying 2 UCB units that were matched at 4 of 6 HLA antigens with the recipient and 3 of 6 HLA antigens between the 2 UCB units. Of 110 patients with hematologic diseases who were treated, 92% experienced neutrophil engraftment a median of 12 days after transplantation. More recently, outcomes after consecutive UCB transplantation in 155 adult recipients with hematologic malignancies were analyzed. In this cohort that also received a reduced intensity conditioning regimen, 38% received transplantation with 2 UCB units to fulfill minimum cell dose targets. Eighty percent of the patients had a neutrophil recovery greater than 500/mm 3 by 60 days after transplantation and 14% experienced graft rejection and autologous recovery of hematopoiesis. The factors associated with a better rate of neutrophil recovery included an elevated CD34+ cell dose, HLA compatibility, and having received a previous autologous stem cell transplantation. Together, these series show that it is possible to use 2 UCB units when the UCB cell content is otherwise limiting and that the cell dose and HLA compatibility are key factors that influence the engraftment of donor cells, particularly in recipients with nonmalignant hematologic disorders.

Cord blood transplantation for thalassemia major—sibling donors

As in other nonmalignant indications for transplantation, the potential for delayed or failed engraftment after cord blood transplantation (CBT) for thalassemia major is balanced by the benefit of a lowered risk of GVHD, a complication that offers no apparent benefit in thalassemia. Thus, the initial reports of CBT for thalassemia focused on the tempo and durability of engraftment and on rates of acute and chronic GVHD. In one retrospective survey of sibling donor cord blood transplantation, 7 of 33 children with thalassemia developed graft rejection after transplantation with an event-free survival of 79%. The rates of acute and chronic GVHD were low, however, and only 4 of 38 evaluable children with sickle cell disease or thalassemia developed acute GVHD after CBT, and 2 of these 4 had an HLA-disparate donor. The Kaplan-Meier probability of chronic GVHD was 6%. Thus, as predicted, the higher incidence of graft rejection after CBT was balanced by a lower incidence of GVHD when compared with rates historically observed after bone marrow transplantation from an HLA-identical sibling donor. Moreover, the low rate of GVHD was associated with excellent survival probability, and none of the 33 patients with thalassemia died after CBT.

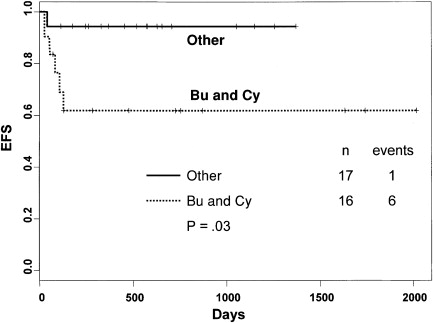

The graft rejection risk after sibling CBT for thalassemia was analyzed with respect to the chemotherapeutic agents of the conditioning regimen and postgrafting immunosuppression regimens. When the conditioning regimen included busulfan (BU) and cyclophosphamide (CY) with or without antithymocyte globulin (ATG), there was a significant association with graft rejection after UCB transplantation for thalassemia. The event-free survival was improved if a combination of BU, CY and thiotepa (TT) or BU, fludarabine (Flu), and TT was administered (94% vs 62%, P = .03) ( Fig. 2 ). In addition, recipients with sickle cell disease and thalassemia who received methotrexate (MTX) as part of GVHD prophylaxis had a poorer event-free survival compared with those who did not receive MTX (55% vs 90%, P = .005) ( Fig. 3 ). Thus, good outcomes were observed among those who did not receive MTX for GVHD prophylaxis and in those who received a modulated conditioning regimen. In a contemporary cohort recently treated from Pavia, Italy, children with thalassemia were prepared for CBT with a combination of BU, Flu, and TT and received cyclosporine alone for postgrafting immunosuppression. All 27 survived free of thalassemia, and none experienced acute or chronic GVHD. The majority of these individuals had stable mixed donor-host chimerism that persisted after UCB transplantation; thus, mixed chimerism early after UCB transplantation was not a predictor of graft rejection ( Fig. 4 ).