32 Tumors of the Salivary Glands

Major Salivary Gland Tumors

Anatomy

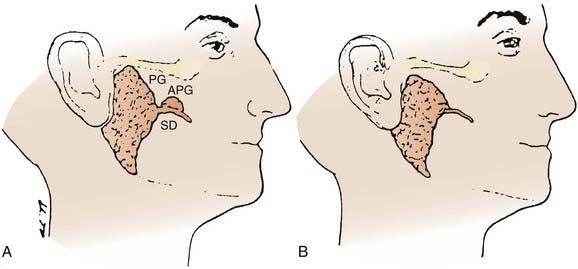

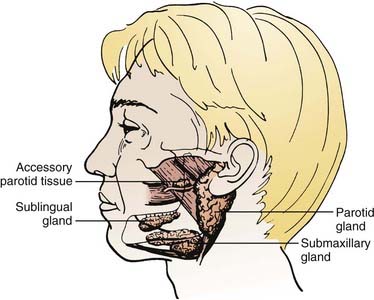

The major salivary glands comprise the parotid, submandibular, and sublingual salivary glands (Fig. 32-1). Each are paired glands that have different secretory functions: (1) parotid gland—serous; (2) submandibular gland—seromucous; (3) sublingual gland—mucous.

FIGURE 32-1 • The anatomic locations of major salivary glands: parotid, submandibular, sublingual.

(From Spiro JD, Spiro RM: Salivary tumors. In Shah J (ed): Cancer of the head and neck, London, 2001, BC Decker, p 241.)

Parotid Gland

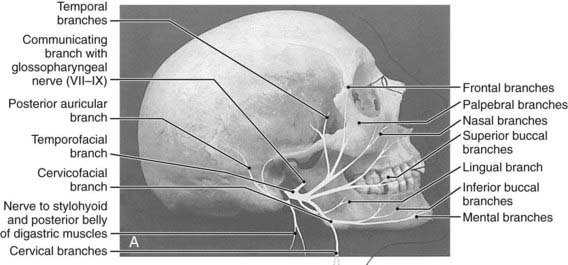

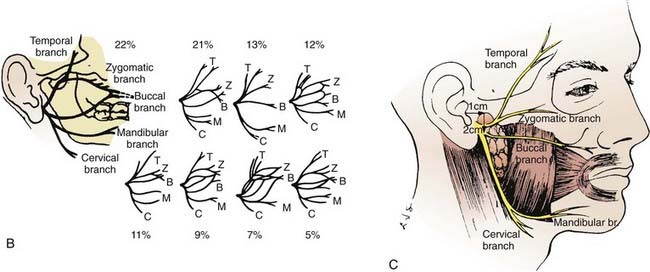

The parotid glands are the largest of the salivary glands (see Fig. 32-1 and Fig. 32-2). These paired glands are surrounded by a discrete capsule and have the following anatomic landmarks: (1) anterior—wraps around the ascending mandibular ramus anterior to the tragus and extends toward the anterior margin of the masseter muscle; (2) posterior—extends from the angle of the mandible under the earlobe toward the mastoid tip; (3) superior—extends to the inferior aspect of the zygoma at the temporomandibular joint level; (4) inferior—extends to the inferior aspect of the angle of the mandible; (5) medial—borders the parapharyngeal-base of skull; (6) lateral—located below the skin of the preauricular cheek–upper neck. The gland is divided into two lobes by the path of the facial nerve, which exits from the stylomastoid foramen (Fig. 32-3): (1) superficial lobe—accounts for 80% of the gland and is located just lateral to the facial nerve; (2) deep lobe—accounts for 20% of the gland and is located medial to the facial nerve and adjacent to the medial aspect of the angle of the mandible and is connected to the superficial lobe by the isthmus (Fig. 32-4). The deep lobe is in close anatomic proximity to the internal carotid artery; the internal jugular vein; the cervical sympathetic chain; and the cranial nerves IX, X, XI, and XII (Table 32-1).

Table 32-1 The Anatomic Relationship of the Major Salivary Glands and Cranial Nerves

| Major Salivary Gland | Adjacent Cranial Nerve | Base of Skull Foramen |

|---|---|---|

| Parotid | ||

| Superficial/deep lobes | Facial nerve (CN VII) | Stylomastoid foramen |

| Deep lobe | Glossopharyngeal nerve (CN IX) | Jugular foramen |

| Vagus nerve (CN X) | Jugular foramen | |

| Accessory nerve (CN XI) | Jugular foramen | |

| Hypoglossal nerve (CN XII) | Hypoglossal canal | |

| Submandibular | Lingual nerve (CNV3) | Foramen ovale |

| Facial nerve (CN VII): | Stylomastoid foramen | |

| Mandibular/cervical branches | ||

| Hypoglossal nerve (CN XII) | Hypoglossal canal | |

| Sublingual | Lingual nerve (CN V3) | Foramen ovale |

CN, Cranial nerve.

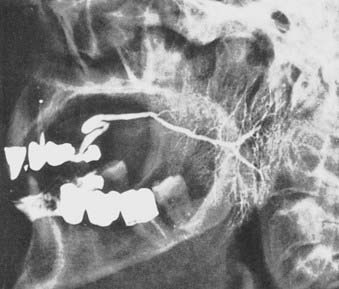

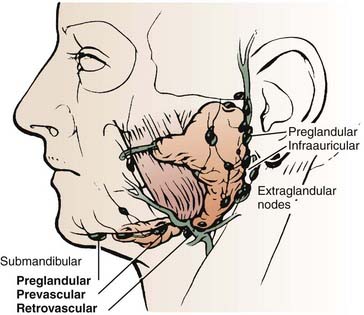

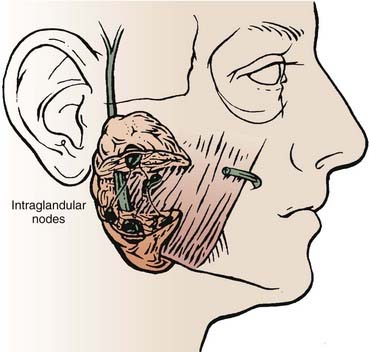

The parotid gland drains into the oral cavity through the Stensen duct (Fig. 32-5). This duct runs from the upper anterior third of the parotid gland and exits through the buccal mucosa by the second molar. The lymphatic drainage of the parotid gland progresses in an orderly fashion. Initially, it drains into the periparotid (Fig. 32-6) and intraparotid (Fig. 32-7) nodes that comprise two groups located within the fascia of the gland in two respective locations: between the gland and the superficial fascia and within the parenchyma. It then drains into the submandibular nodes (level IB), the upper (level II) and mid (level III) cervical nodes, and sometimes to the retropharyngeal nodes. Drainage to the contralateral nodes is very rare. However, it must be considered if the primary tumor extends across the midline or if there is massive ipsilateral cervical node involvement, which may disrupt the lymphatic pathways and cause spread to the opposite side.

FIGURE 32-6 • Periparotid lymph nodes are located on the surface of the superficial lobe but within the fascia.

(From Hoffman H, Funk G, Endres D: Evaluation and surgical treatment of tumors of the salivary glands. In Thawley SE, Panje WR, Batsakis JG, et al (eds): Comprehensive management of head and neck tumors, vol 2, Philadelphia, 1987, WB Saunders, p 1112.)

FIGURE 32-7 • Intraparotid nodes are located within the parenchyma of the gland.

(From Hoffman H, Funk G, Endres D: Evaluation and surgical treatment of tumors of the salivary glands. In Thawley SE, Panje WR, Batsakis JG, et al (eds): Comprehensive management of head and neck tumors, vol 2, Philadelphia, 1987, WB Saunders, p 1112.)

Occasionally, there is an accessory parotid lobe (Fig. 32-8). This lobe has been reported in 21% of normal adult cadavers.1 However, in a review of 2261 patients with parotid lesions at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) between 1939 and 1978, only 23 patients (1%) had an accessory parotid gland.2 Accessory parotid glands are located either cephalad or lateral to the anterior aspect of the Stensen duct and lie over the anterior aspect of the masseter muscle but are separate from the superficial lobe of the parotid gland. Clinically, they are adjacent to the Stensen duct, which is located midway along a line drawn between the tragus of the ear to the lateral upper lip. There can be 1 to 10 tributary ducts from the accessory lobe that will empty into the Stensen duct. This lobe can be clinically significant in that it may be the primary site of a malignant tumor that presents as an asymptomatic swelling in the mid cheek region.

Submandibular Gland

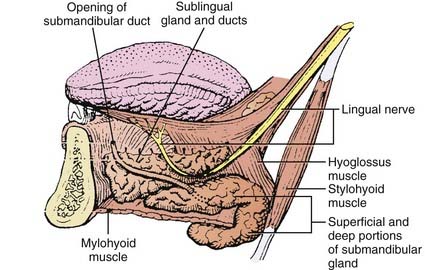

The submandibular gland (see Fig. 32-1) is 25% of the size of the parotid gland and measures 3 to 4 cm. These paired glands are surrounded by a capsule and are located in the upper anterior triangle of the neck. They are medial to the proximal half of the mandible (Fig. 32-9). The majority of the gland is over the external surface of the mylohyoid muscle, which forms the muscular floor of mouth in the region between the insertion of the muscle and the mandible and which divides the gland into contiguous superficial and deep portions (Fig. 32-10). The posterior aspect is anterior to but near the lower anterior margin of the parotid gland. The inferior aspect can extend caudad a fair distance and approaches the level of the hyoid bone. Of clinical importance is the fact that the submandibular gland is lateral to and abuts the lingual nerve (cranial nerve V3) and hypoglossal nerve (cranial nerve XII) and is medial to the marginal mandibular and cervical branches of the facial nerve (cranial nerve VII) (see Table 32-1).

FIGURE 32-10 • Anatomic relationships between the submandibular gland and sublingual gland and the adjacent musculature and cranial nerves.

(A and B from Spiro JD, Spiro RM: Salivary tumors. In Shah J (ed): Cancer of the head and neck, London, 2001, BC Decker, p 241.)

Sublingual Gland

The paired sublingual salivary glands (see Fig. 32-1) are the smallest of the major salivary glands and are approximately 10% of the size of parotid glands. These glands do not have a discrete capsule. They are located in the anterior floor of mouth adjacent to the medial aspect of the mandible and occupy a submucosal position. Sublingual salivary glands are adjacent and superior to the mylohyoid muscle in the area of the sublingual depression. They occupy a position just medial to the inner surface of the mandible near the mental symphysis (see Fig. 32-10). It is clinically important to note that the lingual nerve (cranial nerve V3) courses adjacent to the sublingual gland (see Table 32-1).

Pathologic Conditions

Benign Tumors

Malignant Tumors

Histopathologic Types

The relative incidence of the different histologic types according to gland of origin is detailed in Table 32-2.

Table 32-2 Distribution of Histologic Types of Major Salivary Gland Cancer

| Type | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Parotid (n = 1778 cases) | |

| Mucoepidermoid | 32 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 16 |

| Malignant mixed | 14 |

| Adenoid cystic | 11 |

| Acinic | 11 |

| Undifferentiated and squamous | 16 |

| Submandibular (n = 383 cases) | |

| Adenoid cystic | 41 |

| Acinic | 17 |

| Mucoepidermoid | 12 |

| Malignant mixed | 10 |

| Undifferentiated | 9 |

| Squamous | 9 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 2 |

Data from Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center.1

Mucoepidermoid Carcinoma

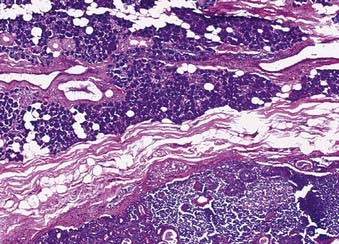

The majority of these cancers are low-grade cancers that tend to be slow-growing, well-circumscribed, and cured by surgery alone. However, some variants are high grades with an aggressive behavior. Mucin production may be absent in high-grade tumors, which are invasive and have an increased risk of spread to lymph nodes (Fig. 32-11). Mucoepidermoid carcinoma is the most common cancer of the parotid gland.3

Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma

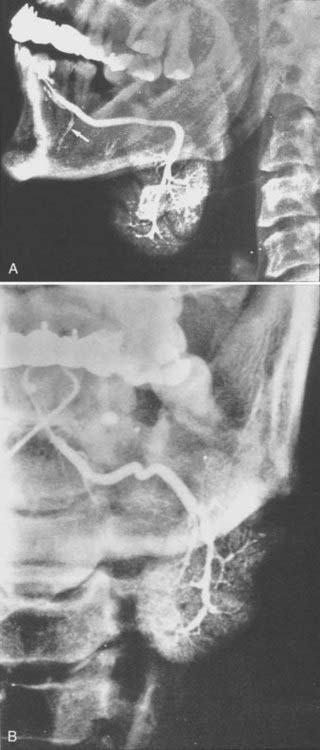

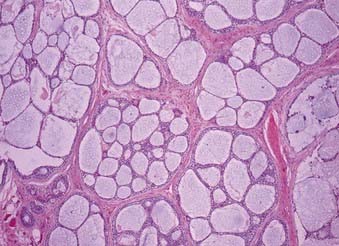

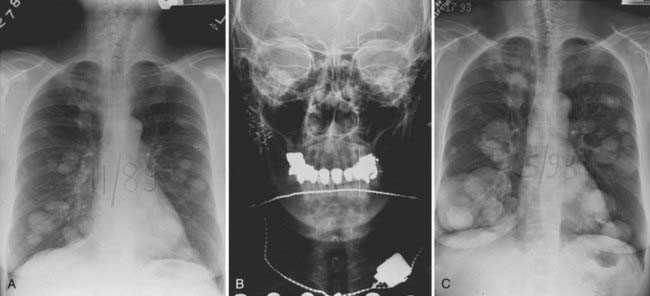

This is the predominant malignant histologic type in submandibular and minor salivary gland tumors.3 The appearance (Fig. 32-12) can vary from a cribriform pattern (differentiated) to a mixed cribriform pattern and solid features (moderately differentiated) to solid features (undifferentiated). Some authors have observed that the solid variety can have a more malignant behavior. The natural history can be varied, ranging from a matter of months to 20 years or more. The first evidence of recurrence can be 20 years after diagnosis, making it very difficult to ever determine that an individual patient is cured. Lymph node spread is distinctly uncommon (<5%). Adenoid cystic tumors can cause perineural spread, which may track along the pathways of the cranial nerves to the base of skull. This is important in planning radiation treatment. Many patients (ultimately up to 40%) will develop pulmonary metastases. Because prolonged survival can occur (10 to 20 years) with pulmonary metastases, the primary site must be managed adequately despite the presence of metastatic disease. An example of the management of the primary site in a patient with adenoid cystic cancer and lung metastases is illustrated in Fig. 32-13.

Histologic Grade

Clinical Presentation and Evaluation

Parotid

Primary Site

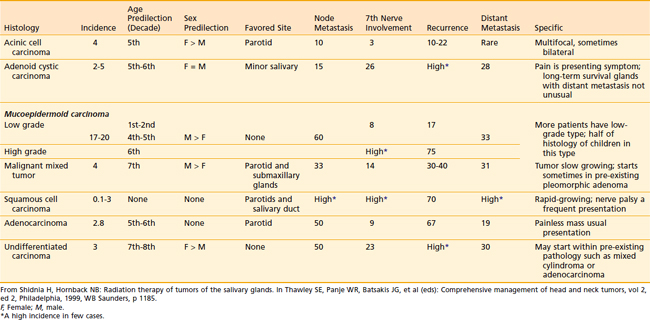

A thorough history and carefully detailed physical examination are always crucial first steps in the evaluation of patients with a parotid mass. The differential diagnoses of a parotid mass include a malignant tumor as well as several types of benign causes (Table 32-3). Parotid malignancy is usually an asymptomatic mass. However, as the lesion progresses and enlarges, episodic pain occurs in 10% to 20% of cases; subsequently, significant pain can result and become constant. Patients can present with complaints of an inability to move one side of the face (cranial nerve VII), a shoulder (cranial nerve IX), or one side of the tongue (cranial nerve XII) as the adjacent cranial nerves become involved by the malignant tumor. Clinical presentations can vary according to the histopathologic findings (Table 32-4).

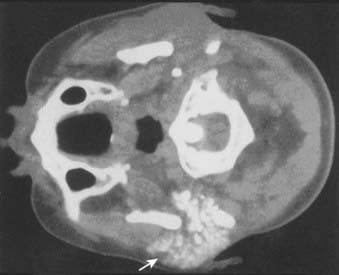

Workup with computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be helpful in selected cases. Slices should cover from above the ears to below the clavicles, thus imaging the base of skull, parotid, retropharyngeal nodes, cervical nodes, and supraclavicular nodes. There are four indications for a pretreatment CT or MRI in parotid gland tumors4: (1) deep lobe parotid tumors, (2) neurologically symptomatic tumors, (3) recurrent tumors, and (4) large tumors.

In general, 75% to 80% of parotid masses are benign and 20% to 25% are malignant. An FNA biopsy is an accurate diagnostic technique with overall sensitivities of greater than 90% and specificities of greater than 95%.5–10 FNA biopsies are as accurate as frozen section analysis in parotid masses. Note that a malignant salivary gland tumor is more likely to be inaccurately diagnosed as a benign lesion than an adenoma is to be erroneously called a malignant lesion. Salivary gland lesions that are particularly associated with difficulties in achieving an accurate diagnosis include acinic cell carcinomas (false-negative confusion for a benign process), monomorphic adenomas (false-positive confusion with an adenoid cystic carcinoma), and lymphoid lesions (both false-negative and false-positive diagnoses).

Lymph Nodes

Although the overall risk (18%)11 of lymphatic spread is less common than for mucosal squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck, it is still essential to carefully evaluate the regional lymph nodes. The influence of tumor histologic features on the frequency of clinically involved nodes at presentation in 474 previously untreated major salivary gland cancers was reviewed by Armstrong from MSKCC.12 These data are presented in Table 32-5. The risk of nodal involvement increases with grade and size. However, adenoid cystic cancer, despite often being aggressive histologically and large in size, had only a 2% rate of clinically evident metastases.

Table 32-5 Clinically Involved Nodes at Presentation in Major Salivary Gland Cancers: The Influence of Tumor Histology

| Histologic Subtypes | Number | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Anaplastic | 6/7 | (86) |

| Epidermoid | 6/28 | (21) |

| Adenocarcinoma | 11/49 | (22) |

| Mucoepidermoid | 30/209 | (14) |

| Malignant mixed | 11/69 | (16) |

| Acinic | 2/55 | (2) |

| Adenoid cystic | 1/55 | (2) |

| Oncocytoma | 0/2 | (0) |

| Total | 67/474 | (14) |

Data from Armstrong et al.12

In the series reported by Armstrong and associates,12 overall clinically occult, pathologically positive nodes occurred in 12% (47/407). By univariate analysis, several factors appeared to predict the risk of occult metastases, but multivariate analysis revealed that only size and grade were significant risk factors. Tumors of 4 cm or more had a 20% (32/164) risk of occult metastases, compared with a 4% (9/220) risk for smaller tumors (P < 0.00001). High-grade tumors (regardless of histologic type) had a 49% (29/59) risk of occult metastases, compared with a 7% (15/221) risk for intermediate or low-grade tumors (P < 0.00001). The effects of tumor histologic anatomy and grade on occult nodal metastases are detailed in Tables 32-6 and 32-7.

Table 32-6 Effect of Tumor Histology on Occult Lymph Node Involvement in Major Salivary Gland Cancers

| Histologic Subtypes | Number | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Epidermoid | 9/22 | (41) |

| Adenocarcinoma | 7/38 | (18) |

| Mucoepidermoid | 26/179 | (14) |

| Acinic | 2/53 | (4) |

| Adenoid cystic | 2/54 | (4) |

| Anaplastic | 1/1 | |

| Malignant mixed | 0/58 | |

| Oncocytoma | 0/2 | |

| Total | 47/407 | (12) |

Data from Armstrong et al.12

Table 32-7 Effect of Tumor Grade on Occult Lymph Node Involvement in Major Salivary Gland Cancer

| Tumor Grade | Number | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Low | 2/125 | (2) |

| Intermediate | 13/96 | (14) |

| High | 29/59 | (49) |

Data from Armstrong et al.12

It is rare for a low-grade tumor to metastasize to the regional nodes. All high-grade lesions carry a significant risk for nodal metastasis irrespective of the histologic type. High–T stage lesions are associated with an increased incidence of nodal metastasis. Submandibular or sublingual primary salivary malignancies have an increased risk for nodal spread compared with parotid salivary malignancies. The histologic type can influence the risk for nodal metastasis as well. Mucoepidermoid carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and undifferentiated carcinoma are associated with a high incidence of nodal metastasis; however, adenoid cystic carcinoma, malignant mixed carcinoma, and acinic cell carcinoma have a low incidence (see Tables 32-5 and 32-6).

Distant Spread

The most likely site for distant metastasis is the lung, followed by the bones and liver. Adenoid cystic carcinoma, malignant mixed tumor, and mucoepidermoid carcinoma have a risk for distant metastases that ranges from 25% to 35%.13 Careful examination of the lungs, percussion of the bones, and palpation of the liver should be documented.

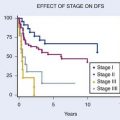

Staging

Periodically, the staging criteria are reviewed and modified to better establish a system that reflects contemporary technology and therapeutic interventions. The current AJCC Cancer Staging Manual (Table 32–8) represents the seventh edition, published in 2010.14 The following examines the changes from the sixth edition (2002)15 as they relate to major salivary gland tumors.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree