Sinonasal malignancies are rare cancers that present significant diagnostic and management challenges. As tumors with a diverse histologic spectrum and wide-ranging clinical behavior, they often present at advanced stages, involving anatomically complex regions that are difficult for the surgeon to navigate. Sinonasal tumors straddle critical areas that influence the physiology of mastication, speech, swallow, nasal continence, vision, and central nervous function. These tumors and their treatment therefore commonly inflict high morbidity and mortality.

Optimizing care to maximize disease control, function, and cosmesis requires a dedicated multidisciplinary team of surgeons, radiation oncologists, medical oncologists, as well as specialists to facilitate post-treatment rehabilitation. Reliance on expert imaging and pathology is critical to selection of treatment. Overall, successful management is predicated on understanding tumor biology and practicing sound oncologic principles to produce the best outcomes by balancing control of disease against preservation of function and quality of life (QOL).

The nasal cavity serves as the inlet to the upper airway, beginning at the anterior nares and ending at the posterior choanae that open into the nasopharynx. It provides a portal of entry that filters, humidifies, and warms incoming air traveling to the lungs. The nasal cavity is divided in the midline by the nasal septum, which is composed of the septal cartilage and the vomer bone, lined on each side by the nasal mucosa.

The nasal cavity confines are partly cartilaginous and partly bony, and its floor is purely bony. Laterally, the nasal cavity contains the nasal conchae. The inferior concha is part of the nasal cavity, while the superior and middle conchae are composite parts of the ethmoid complex. The mucous membrane lining the nasal cavity is densely adherent to the underlying periosteum and perichondrium. The majority of the mucous membrane is pseudostratified columnar ciliated epithelium of the Schneiderian type. The lining is highly vascular and contains mucous glands, minor salivary glands, and melanocytes.

The olfactory neuroepithelium that is responsible for the sense of smell overlies the cribriform plate in the roof of the nasal cavity. The lateral nasal wall bears the conchae (or turbinates), and the meati (or air spaces) between them contain the openings of the paranasal sinuses. The inferior meatus is located below and lateral to the inferior concha and receives the opening of the nasolacrimal duct on the anterior portion of its lateral wall. The ostium of the maxillary sinus opens into the ethmoidal infundibulum of the middle meatus, whereas the sphenoid sinus drains into the sphenoethmoidal recess above the uppermost concha.

The blood supply to the nasal cavity is from branches of the external carotid arteries (sphenopalatine branches of the internal maxillary artery and facial artery) and internal carotid arteries (anterior and posterior ethmoid branches of the ophthalmic artery). The veins of the nose arise in the dense venous plexi that are especially concentrated on the inferior nasal concha, the inferior meatus, and the posterior septum; the venous drainage parallels the arteries. Lymphatic drainage is primarily to the jugulodigastric nodes and the retropharyngeal nodes.

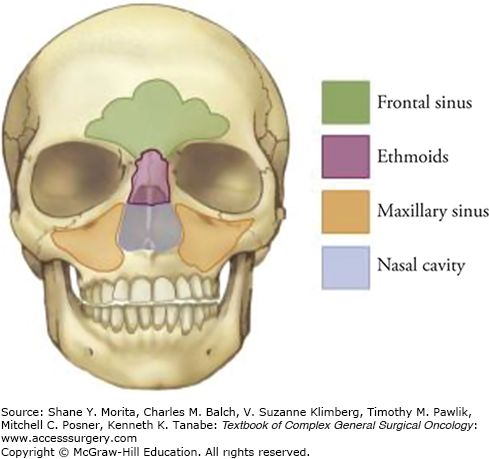

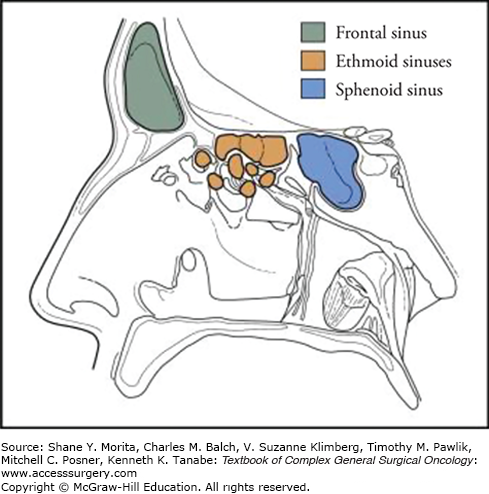

The nasal cavity is surrounded by air-filled bony spaces that are lined with mucosa, called paranasal sinuses (Fig. 59-1), the largest of which are the maxillary sinuses. Ethmoid air cells occupy the superior aspect of the nasal cavity and separate it from the anterior skull base at the level of the cribriform plate. For purposes of staging malignant tumors, the lower half of the nasoethmoid region, including the inferior turbinate and concha, is considered the nasal cavity, whereas the upper half, consisting of the middle and superior turbinates and ethmoid air cells, constitutes the ethmoid region. Superoanteriorly, the frontal sinus contained within the frontal bone forms a biloculated or multiloculated pneumatic space. The sphenoid sinus at the superoposterior part of the nasal cavity is located at the roof of the nasopharynx. The sphenoid sinus is divided by a septum and may be multiloculated. The relationship of the paranasal sinuses to each other is shown in Figure 59-2.

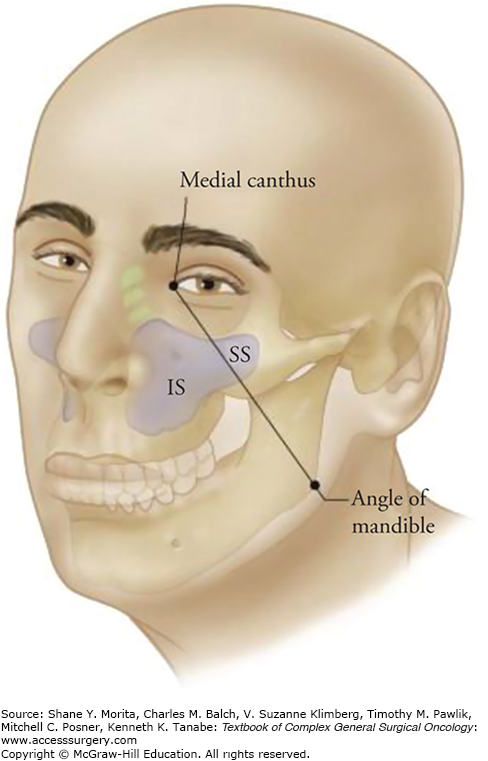

Anatomic principles not only facilitate surgical approaches but have practical implications for prognosis, especially for posteriorly and superiorly located tumors. Öhngren’s line1 is an imaginary plane that extends from the medial canthus of the eye to the angle of the mandible (Fig. 59-3). Infrastructural maxillary sinus lesions (anterior and inferior to Öhngren’s line) tend to present earlier and are more amenable to complete surgical resection. Suprastructural lesions (superior and posterior to the line), usually present at more advanced stages, are more likely to involve critical structures (e.g., orbit, carotid, infratemporal fossa, pterygopalatine fossa, skull base) and are much more challenging to extirpate surgically. As such, suprastructural maxillary lesions typically have a worse prognosis.

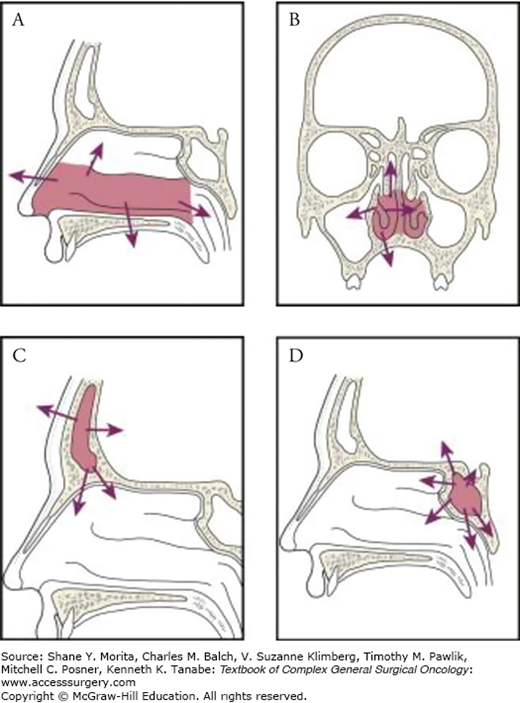

Numerous pathways of local tumor spread exist, including extension through the bony skeleton, into soft tissue or the skin, via intracranial or intraorbital invasion, or via perineural spread. Tumors of the infrastructure of the maxillary antrum may extend through the floor of the antrum into the oral cavity, through its medial wall into the nasal cavity, through its anterior wall to the soft tissues of the cheek, or through its lateral wall into the masticator space. On the other hand, tumors of the suprastructure spread by extension through the posterior wall of the sinus into the pterygomaxillary space, infratemporal fossa, and the middle cranial fossa; through the roof of the antrum into the orbit; or via the ethmoid cavities to the anterior cranial fossa. Primary malignant tumors of the nasal cavity may invade the hard palate, maxillary antrum, ethmoid cavities, or orbit by local extension (Fig. 59-4A). Ethmoid tumors can extend to the sphenoid sinus, anterior cranial fossa, orbits, nasal cavity, or nasopharynx or into the maxillary antrum (Fig. 59-4B). Although primary tumors of the frontal and sphenoid sinuses are uncommon, local spread from these tumors into the cranial cavity with invasion of the dura and brain seldom leaves them suitable for curative resection (Figs. 59-4C and 59-4D). Perineural invasion (PNI) is not uncommon and is an extremely challenging feature of sinonasal tumors.

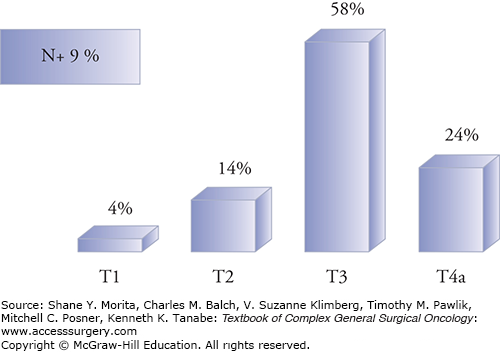

Dissemination to regional lymph nodes in the neck is relatively infrequent, occurring in less than 10% of all patients with paranasal sinus malignancies.2 Such low incidence is below the usual 15% to 20% threshold warranting elective neck treatment at most institutions. Certain subtypes (such as esthesioneuroblastoma), or highly advanced stage disease, have higher rates of regional metastases and may merit consideration for elective neck dissection. Similarly, approximately 17% to 25% of all sinonasal cancers develop distant metastases. Adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC) is associated with exceptionally high rates of distant metastases (typically to the lungs) over decades, while other aggressive histologies such as sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma (SNUC) commonly metastasize (to the lungs or bone) within a few years of diagnosis.

Paranasal sinus malignant tumors are uncommon, and for classification purposes typically exclude nasopharyngeal cancers. They comprise less than 5% of all head and neck cancers, and the incidence varies somewhere between 0.5 and 1.0 per 100,000 people in Western countries3–5 and 3.6 per 100,000 people reported in Japan.6 A significant majority of tumors occur at an older age (greater than 50 to 60 years).7 The maxillary sinus is the most common site of paranasal sinus malignancies (50% to 70%), followed by the nasal cavity (15% to 30%) and ethmoid sinus (10% to 20%).6 Tumors arising primarily from the frontal and sphenoid sinuses are exceedingly rare, and are associated with poor prognosis because they typically present with advanced disease.

Paranasal sinus malignancies can be classified into epithelial and nonepithelial categories. Unsurprisingly, a number of subtypes have been linked to environmental or occupational exposure to toxic inhalants, with the highest risks found for workers in the wood, leather, textile, and aluminum industries.8–10 The most commonly encountered epithelial subtypes are squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), ACC, and adenocarcinoma. Well-known nonepithelial subtypes include lymphoma (including natural killer/T-cell lymphoma, previously known as lethal midline granuloma) esthesioneuroblastoma, SNUC, and mucosal melanoma. The World Health Organization (WHO) comprehensively classifies the wide array of known sinonasal malignancies, with 44 distinct histologic entities (Table 59-1).11 The most common ones are discussed below.

World Health Organization Histological Classification of Paranasal Sinus Malignancies

| Epithelial malignancies |

|---|

| Squamous cell carcinoma |

| Verrucous carcinoma |

| Papillary squamous cell carcinoma |

| Basaloid squamous cell carcinoma |

| Spindle cell carcinoma |

| Adenosquamous carcinoma |

| Acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma |

| Lymphoepithelial carcinoma |

| Sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma |

| Adenocarcinoma |

| Intestinal-type adenocarcinoma |

| Nonintestinal-type adenocarcinoma |

| Salivary gland-type carcinomas |

| Adenoid cystic carcinoma |

| Acinic cell carcinoma |

| Mucoepidermoid carcinoma |

| Epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma |

| Clear cell carcinoma N.O.S. |

| Myoepithelial carcinoma |

| Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma |

| Polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma |

| Neuroendocrine tumors |

| Typical carcinoid |

| Atypical carcinoid |

| Small cell carcinoma, neuroendocrine type |

| Soft tissue malignancies |

| Fibrosarcoma |

| Malignant fibrous histiocytoma |

| Leiomyosarcoma |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma |

| Angiosarcoma |

| Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor |

| Bone and cartilage malignancies |

| Chondrosarcoma |

| Mesenchymal chondrosarcoma |

| Osteosarcoma |

| Chordoma |

| Hematolymphoid malignancies |

| Extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma |

| Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma |

| Extramedullary plasmacytoma |

| Extramedullary myeloid sarcoma |

| Histiocytic sarcoma |

| Langerhans cell histiocytosis |

| Neuroectodermal malignancies |

| Ewing sarcoma |

| Primitive neuroectodermal tumor |

| Olfactory neuroblastoma |

| Melanotic neuroectodermal tumor of infancy |

| Mucosal malignant melanoma |

| Germ cell malignancies |

| Teratoma with malignant transformation |

| Sinonasal teratocarcinosarcoma |

Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common of the sinonasal malignancies (40% to 50% incidence). These tumors arise from the respiratory epithelium and exhibit varying degrees of keratinization. Substantial evidence supports the hypothesis that smoking is a predominant risk factor, much as it is for other aerodigestive tract sites. Other risk factors linked to SCC include (but are not limited to) exposure to aflatoxin, chromium, nickel, and arsenic. In terms of increased risk from exposure, a meta-analysis of 12 case-control studies identified an odds ratio of 13.9 for workers in the food preservation industry.12 A viral etiology is also associated with sinonasal SCC: HPV subtypes 6 and 11 are associated with inverted papilloma, of which approximately 10% degenerate into SCC. SCC tends to recur more quickly than other sinonasal tumors, with average time to recurrence reported to be 2 to 3 years.13 The incidence of regional neck metastasis may be relatively higher at 20% to 25%,3 so that elective neck dissection should be considered in selected situations.

Adenocarcinoma make up between 13% and 19% of paranasal sinus malignancies, and their glandular architecture implies they arise from surface epithelium or seromucous glands.11 Besides those arising from minor salivary origin, adenocarcinomas are typically divided into “nonintestinal” and “intestinal types.” Nonintestinal adenocarcinomas confer a relatively good prognosis. By contrast, intestinal-type adenocarcinomas, which are histologically similar to colorectal adenocarcinomas, are locally aggressive with a high rate of spread to neck lymph nodes. The 5-year overall survival has been reported to be approximately 50%.2

Among the known occupational hazards associated with paranasal sinus malignancies, the most indisputable causative connection has been with wood dusts, which result in up to a 900-fold increased risk of developing adenocarcinoma, specifically the intestinal-type.14–16 Other pooled analyses have suggested an odds ratio for exposed males in wood-related occupations to be 13.5, increasing to 45.5 for longer duration of exposures.6 It appears that exposure for as little as 5 years can place workers at risk, whereby the latency before diagnosis is approximately 40 years. Leather-related dust exposure also appears associated with adenocarcinoma development, but to a lesser degree.17

Minor salivary glands exist throughout the sinonasal cavities, and malignant tumors of these glands include mucoepidermoid carcinoma, acinic cell carcinoma, and ACC. ACC comprise 6% to 10% of paranasal sinus malignancies, and are the most common sinonasal tumors of minor salivary gland origin. They are often classified by their tubular, cribriform, or solid growth pattern, with solid ACC displaying the most aggressive behavior. Of significant interest is the high rate of PNI and long-term distant metastases associated with ACC, though its biologic behavior requires further investigation.18,19 While 5-year survival ranges from 73% to 90%, continued attrition from long-term failure reduces 15-year disease-specific survival to as low as 40%.20 Unlike other tumor types, the high recurrence rate with ACC takes many years to manifest and therefore long-term surveillance is advisable for these patients.

Esthesioneuroblastomas make up less than 5% of paranasal sinus malignancies and are of neuroectodermal origin derived from olfactory epithelium. They are characterized by a lobular appearance with neuroblasts and neurofibrils embedded among highly vascular fibrous stroma. The Kadish staging system has been the most widely accepted as an effective means to predict disease-free survival: group A tumors are limited to the nasal cavity, group B tumors extend to the paranasal sinus, and group C tumors extend beyond the nasal cavity and sinuses. A modified Kadish system includes group D tumors, which have cervical lymphadenopathy or distant metastasis. Esthesioneuroblastomas are typically radiosensitive but eventually develop cervical neck metastases in 20% to 25% of patients.21 This has prompted controversy about the utility of elective neck dissection or elective neck irradiation in patients with esthesioneuroblastoma. Approximately 50% of esthesioneuroblastomas are first discovered as Kadish group C, and these patients have reported 5-year survival rates of 50% to 70%.22–24

Sinonasal undifferentiated carcinomas are aggressive, high-grade malignancies without clear squamous or glandular differentiation. The cells of origin remain unclear but they are thought to arise from Schneiderian epithelium or nasal ectoderm. Their histological appearance is of solid sheets and nests of high-grade pleomorphic cells with profuse mitotic figures and necrosis. Immunohistochemistry for SNUCs is nonspecific, lacking reactivity for neuroendocrine markers, but is useful to exclude similar entities such as esthesioneuroblastoma, for which it was originally considered. The clinical presentation of SNUCs is often marked by rapid growth and extensive disease; more than 80% of patients demonstrate T4 lesions at presentation.25,26 Trimodality treatment including surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy is typically recommended if the patient is able to tolerate it. Due to the aggressive nature of these tumors, patients should be considered for a therapeutic trial if available. Induction chemotherapy followed by surgery and radiation provides both local-regional and systemic therapy. In patients who achieve a complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy, radiation may result in good local-regional control of tumor. Many SNUCs are unresectable and for those who are surgical candidates, the appropriate order of treatment (induction vs. postoperative chemoradiation) also remains unclear. Nodal disease has been reported at 26% to 27%, meriting consideration of bilateral elective treatment of the neck. The 5-year overall survival is 22% to 43%, with as many as 65% of patients developing distant metastases.25

While it is comparatively less common in the paranasal sinuses than the other tumor types discussed here, the sinonasal cavities are the most frequent site for mucosal melanomas in the head and neck. Mucosal melanomas comprise less than 1% of all melanomas and are less often pigmented than cutaneous lesions, though they similarly stain positive for S-100, HMB-45, and melanin A. They also behave differently enough to merit their own staging system. Mucosal melanomas are extremely aggressive, with all lesions classified as T3 and stage III at minimum. While surgical resection remains the standard of care, the majority of patients ultimately develop distant metastases, with the most common sites being lung, liver, and bone.27 The 5-year overall survival has been reported to be between 25% and 42%.28,29

Sarcomas of the sinonasal region represent diverse histologies and correspondingly varied aggressiveness. Prognosis is intermediate for patients with malignant fibrous histiocytoma and fibrosarcoma, and poor for patients with high-grade sarcomas such as angiosarcoma and rhabdomyosarcoma. Rhabdomyosarcomas are not typically found in adults but are the most common pediatric paranasal sinus malignancy, with the orbit being the most common subsite and having the most favorable prognosis.

Chrondrosarcomas are a heterogeneous group of malignancies of cartilaginous origin. Pathologic diagnosis can be challenging as the spectrum ranges from a well-differentiated benign-looking cartilaginous tumor to a high-grade aggressive malignancy. Approximately 30% of pathologic diagnoses of benign chordoma, chondroma, and others may be revised to low-grade sarcoma on careful review.30 Osteosarcomas are rare but may arise from the maxilla, ethmoid, sphenoid, or frontal bones. Most such lesions are high-grade malignancies and portend a poor prognosis.

Though sinonasal lymphomas are uncommon within Western nations, they are the second most frequent subsite for lymphomas in Asian countries.31 Non-Hodgkin-type lymphomas predominate, including B-cell, T-cell, and natural killer/T-cell (NK/T) (previously described as lethal midline granuloma) phenotypes. Lymphomas classically occur in patients older than 60 years and are treated with chemoradiation. The NK/T subtype is especially aggressive, with an angioinvasive growth pattern resulting in bony erosion and necrosis.

Because the paranasal sinuses are air-filled structures with significant potential space, sinonasal neoplasms rarely produce symptoms at an early stage. Symptoms usually develop as a result of obstruction of the involved sinus or nasal cavity or when the tumor breaks through the walls of the involved sinus and produces symptoms relating to the local invasion of adjacent tissues. Thus the majority of patients present with advanced stage tumors (Fig. 59-5). Even when symptoms from sinonasal tumors are present, they may initially appear nonspecific or innocuous: the most common complaints mimic sinusitis and include nasal obstruction (61%), localized pain (43%), epistaxis (40%), swelling (29%), and nasal discharge (26%). More ominous symptoms include epiphora (19%), a palate lesion (10%), diplopia (8%), cheek numbness (8%), decreased vision (8%), neck mass (4%), proptosis (3%), and trismus (2%). Accordingly, a high index of suspicion should be maintained, especially in older patients with unilateral symptoms.

As tumors extend beyond the bony confines of the sinonasal tract, they can affect other structures and cause swelling or a mass in the hard palate, upper gum, gingivobuccal sulcus, or cheek. Loose teeth, numbness of the skin of the cheek and upper lip, diplopia, and proptosis are signs of local extension of disease. More advanced tumors may present with trismus consequent to extension into the masticator space with infiltration of the pterygoid muscles. Posteriorly based sinonasal tumors, especially those in the sphenoid sinus, may present with anesthesia in the distribution of the fifth cranial nerve or paralysis of the third, fourth, or sixth cranial nerves. Anosmia is a common symptom in patients with esthesioneuroblastoma, but it can occur with any advanced tumor of the nasoethmoid complex.

After taking a detailed history, a thorough clinical head and neck examination should be performed. This includes an ophthalmologic assessment for propotosis, epiphora, visual acuity changes, or extraocular muscle restriction or entrapment; a neurologic assessment for muscle impingement, numbness, paresthesias; and dental assessment for palatal lesions, trismus, or loose dentition. Nasal endoscopy with rigid or flexible fiberoptic endoscopy should also be performed to evaluate for natural sinus drainage outflow tracts, cerebrospinal fluid leakage, suspicious masses and their sites of origin. A topical spray of 0.5% phenylephrine and 4% lidocaine generally provides adequate decongestion and topical anesthesia to allow adequate examination of the nasal cavity. To prevent bleeding, care must be exercised to avoid trauma and manipulation of the tumor. Neoplasms causing sinonasal obstruction can induce inflammatory, polyp-like changes in the mucosa of the nasal cavity. Endoscopic evaluation alone is not sufficient to define the nature and extent of a sinonasal tumor. Radiographic imaging is essential in nearly all patients suspected of having a neoplasm of the nasal cavity or paranasal sinuses.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree